Document 13000781

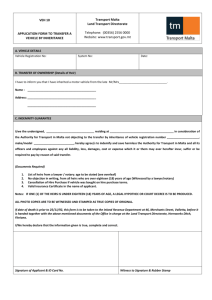

advertisement