Tax Reform, Labour Supply and Earnings Growth Richard Blundell Economic Policy Lecture

advertisement

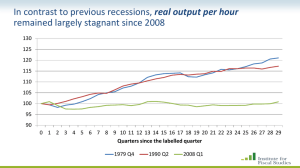

Tax Reform, Labour Supply and Earnings Growth Economic Policy Lecture ZEW September 11th 2014 Richard Blundell University College London and Institute for Fiscal Studies Slide Presentation [Draft paper available] © Institute for Fiscal Studies Tax Reform, Labour Supply and Earnings Growth • Focus here on the labour market, human capital and earnings tax reforms. • Even before the recent crisis, governments around the EU faced pressure to increase employment and earnings. • The current recession has added to pressure on government revenues. • Ask two general questions: • What are the key margins where might expect tax/welfare reform to have most impact on earnings and employment growth? • How has this changed in the light of the great recession? 1. Develop an empirical foundation for tax design and reform. 2. Use the Mirrlees Review (2011) as a running example. 3. Overview of main issues and prospects with current tax systems. Summary overview...… • Current systems remain unnecessarily complicated and induce too many people not to work or to work too li5le. • Target work incen9ves where they are most effec9ve – our simula9ons show key increase in work/earnings, – reducing means-­‐tes9ng and improving the flows into work for lower educa9on mothers and maintaining work for those aged 55+. • Integrate overlapping benefits -­‐ a single integrated benefit – Mirrlees -­‐ ‘ifs’ reforms. • Reduce disincen9ves at key margins for the educated – enhancing working life9me and the career earnings profile, – simula9ons show significant impact on human capital. • Align tax rates at the margin across income sources. • In this talk I draw loosely on four of my recent ‘post-Mirrlees’ studies: – ‘Labor Supply and the Extensive Margin’; AER 2011 – ‘Empirical Evidence and Tax Reform’; JEEA 2012 – ‘Hours of Work and the Optimal Taxation of Low Income Families’; ReStud 2012 – ... and on-going work with Antoine Bozio, Guy Laroque and Andreas Peichl. • Additional question: To what extent do dynamic ‘longer-run’ issues change our view of earnings tax reform? • Labour Supply, Human Capital and Welfare Reform’; NBER 2013 • Overall question: How should we assemble the empirical foundations for tax policy design? • Consider the role of evidence under five headings: 1. Key margins of adjustment to reform 2. Measurement of effective incentives 3. The importance of information and complexity 4. Evidence on the size of responses 5. Implications for policy design • Use these to build an empirically based agenda for reform – > an efficient redesign of tax policy…. • What have we learned … so far? • Are the proposals still relevant post recession? • There are common key points in the life-­‐cycle where individuals are likely to be most responsive to effec9ve tax and welfare incen9ves – Derives from compara9ve work across UK, US, FR and DE, – Labour market entry, parents of younger children and older workers. • Human capital on the job is strongly complementary with formal educa9on – Pay-­‐off to on the job experience and training is low for those with lower educa9onal qualifica9ons. • Effec9ve tax rates can be extremely high for no good reason – Interac9ons of means-­‐tested programmes at the bo5om and employer/ employee taxes /contribu9ons in the middle. • Effec9ve budget constraints are complex and oXen poorly understood – Working age parents in France face the interac9on of more than 17 different overlapping taxes, employer contribu9ons and benefits – only 13 in UK! • Differen9al rates on similar sources of remunera9on induce significant tax shiXing and avoidance. • Let’s take a run through the evidence….. The five steps…. 1. Key margins of adjustment to reform • A ‘descriptive’ analysis of the key aspects of observed behaviour – not ‘causality’ just the correlations in the data, – the key facts! • Where is it that individuals, families and firms most likely to respond? – e.g. the margins of labour market adjustment. Key margins of adjustment Employment for men by age – FR, UK, US & GER 2007 Blundell, Bozio, Laroque and Peichl (2014) and for women ….. Female Employment by age Blundell, Bozio, Laroque and Peichl (2014) Female Hours by age Blundell, Bozio, Laroque and Peichl (2014) 1.6 1.8 log wage 2 2.2 2.4 2.6 Wage profiles by education and age – UK Women 20 30 40 50 age secondary further higher Source: Blundell, Dias, Meghir and Shaw (2013) Women’s employment - UK Part−time employment 0 .5 .6 .05 employment rates .1 .15 employment rates .7 .8 .2 .9 .25 1 All employment 20 30 40 50 20 age secondary 30 40 age further Source: Blundell, Dias, Meghir and Shaw (2013) higher 50 Women’s employment after childbirth - UK Source: Blundell, Dias, Meghir and Shaw (2013) Wages by education and age – US Men 3.5 3.3 Some College 3.1 2.9 High School 2.7 2.5 2.3 Drop out 2.1 1.9 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 Notes: PSID, 1996-2010, mean log wage by age, cohort effects removed Source: Blundell, Pistaferri and Saporta (2013) Employment for men by education and age – US 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 Less than College College 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 Blundell, Bozio and Laroque (2011) Summary so far…key facts • A lifetime view of employment and hours – differences accentuated at particular ages and for particular demographic groups, – higher attachment to the labor market for higher educated, career length matters. • Wages grow stronger and longer over the lifetime for higher educated – human capital accumulation during work is shown to be complementary to education, – essential to explain employment and wage profiles for those with more education. • Other key facts include growth of high employment incomes and consequent impact on inequality. 2. Measurement of effective incentives • Precisely how do tax policies impact on the incentives facing the key players? • e.g. overlapping taxes, tax credits and welfare benefits. – What are the ‘true’ effective tax rates on (labor) earnings? Budget Constraint for Single Parent: UK 2011 $26,000 $24,000 Net income (£/year) $22,000 $20,000 $18,000 $16,000 $14,000 Current system $12,000 $10,000 $0 $2,000 $4,000 $6,000 $8,000 $10,000 $12,000 $14,000 $16,000 $18,000 $20,000 Gross annual earnings Notes: wage £6.50/hr, 2 children, no other income, £80/wk rent. Ignores council tax and rebates © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Interactions matter: Budget Constraint for Single Parent in UK Notes: wage £6.50/hr, 2 children, no other income, £80/wk rent. Ignores council tax and rebates Universally Available Tax and Transfer Benefits in US (Single Parent with Two Children, 2008) Source: Urban Institute (NTJ, Dec 2012). Notes: Value of tax and value transfer benefits for a single parent with two children. © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Effective Marginal Tax Rates (US Single Parent with Two Children in Colorado, 2008) Source: Urban Institute (NTJ, Dec 2012). Notes: Value of tax and value transfer benefits for a single parent with two children. © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% Average EMTRs for different family types: UK 2011 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 Employer cost (£/week) Single, no children Partner not working, no children Partner working, no children Lone parent Partner not working, children Partner working, children Mirrlees Review (2011) 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% Average PTRs for different family types: UK 2011 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 Employer cost (£/week) Single, no children Partner not working, no children Partner working, no children Lone parent Partner not working, children Partner working, children Mirrlees Review (2011) 3. The importance of information and complexity • How is the policy likely to be understood by the agents involved? • For example, how ‘salient’ are the various tax and welfare benefit incentives? – ‘Take-up’ of welfare and tax credits among eligible families – ‘Bunching’ at kink points 0 Probability of take-up .2 .4 .6 .8 1 Variation in tax credit ‘take-up’ with value of entitlement 0 50 100 Lone parents © Institute for Fiscal Studies 150 200 WFTC entitlement (£/week, 2002 prices) Couples Budget Constraint for Single Parent: UK Notes: wage £6.50/hr, 2 children, no other income, £80/wk rent. Ignores council tax and rebates Mirrlees Review (2011) Are these hours rules salient? Single Women (aged 18-45) - 2002 Blundell and Shephard (2010) Hours’ distribution for lone parents, before WFTC Blundell and Shephard (2010) Hours’ distribution for lone parents, after WFTC Blundell and Shephard (2010) Bunching at Tax Kinks Married Tax Filers: US Source: Saez (2010) © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Bunching at Tax Kinks and the EITC One child families: US Source: Saez (2010) © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Universally Available Tax and Transfer Benefits in US (Single Parent with Two Children, 2008) Source: Urban Institute (NTJ, Dec 2012). Notes: Value of tax and value transfer benefits for a single parent with two children. © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Bunching at Tax Kinks and the EITC One child families: US Source: Saez (2010) © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Taxes on Higher Incomes Marginal tax rates by income level, UK 45% 40% 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% Earned income Self employment income Dividend income 10% 5% 0% $0 $10,000 $20,000 $30,000 $40,000 $50,000 Gross income Note: assumes dividend from company paying small companies’ rate. Includes income tax, employee and self-employed NICs and corporation tax. © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Bunching at the higher rate threshold, UK Number in each £100 bin 300000 250000 200000 150000 100000 50000 0 Distance from threshold © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Composi9on of income around the higher rate tax threshold Total income per £100 bin (£ billion) Interest $9 $8 $7 $6 $5 $4 $3 $2 $1 $0 -­‐$1 Property Dividends Other investment income Self employment Other Pensions Benefits Employment Distance from threshold © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Deductables 4. Evidence on the size of responses • This is where the rigorous econometric analysis of structure and causality comes into play. • Eclec9c use of two approaches: 1. Quasi-­‐experimental/RCT/reduced form evalua9ons of the impact of (historic) reforms • robust but limited in scope. 2. A ‘structural’ es9ma9on based on a the pay-­‐offs and constraints faced by individuals and families • comprehensive in scope and allow simula9on, but fragile. • account for life-­‐cycle facts, effec9ve tax rates, and salience/s9gma. Ø What do we need to get observed responses to match with incen9ves? • Labour supply elas9ci9es vary in key ways by educa9on group, family type and age. No single number! – large at certain key points in the working life and for certain demographic groups, this is where tax and welfare benefit distor9ons are important. • Informa9on, s9gma and salience ma5er – dis9nguish large reforms that are well understood. • Taxable income is responsive for self-­‐employed and top earners – but oXen reflects tax shiXing and avoidance. • Experience ma5ers: especially for those with above basic educa9on – and, it seems, only for those in full-­‐9me employment, – can explain ‘success’ of simpler simula9ons of reforms for low-­‐wage workers. • To match employment, hours and wages over the life-­‐cycle it is key is to allow complementarity between human capital investments – between schooling and ‘on the job’ investments. Data and Simulations for Wages by education and age – UK Women, BHPS Source: Blundell, Dias, Meghir and Shaw (2013) Data and Simulations for Women’s Employment - UK Source: Blundell, Dias, Meghir and Shaw (2013) Younger Workers • Extensive margin responses are low (e≈.15) at young ages for college educated – but much higher (≈.9) for mothers with basic educa9on & kids in 3-­‐7 age range, and larger than intensive elas9ci9es which are more modest (≈.5) – extensive/intensive elas9ci9es imply op9mal earned income tax credits, – small human capital/experience effects for low educated so li5le progressivity but need to account for ‘take-­‐up’. Human capital effects • Two forms of human capital – schooling and on-­‐the-­‐job investment – the hourly wages of those with more educa9on are higher, and grow faster and for longer into the working life -­‐ formal educa9on complements experience capital, – for educated young workers, unlikely to respond to tax incen9ves during career, rather effect career length and re9rement. Older workers… • Elas9ci9es increase for 60+ age group for both men and women – appear to remain higher for women at both margins, – elas9ci9es increase as mandatory re9rement restric9ons/ earnings tests are liXed and actuarial fairness introduced, – joint re9rement ma5ers above pure incen9ves. • Lower educated are responsive to incen9ves in disability insurance, social security and medical insurance. • Higher educated more responsive too at these ages – larger density of workers around the work/no-­‐work margin, – wage and wealth effects become important. • Response elas9ci9es are sizable but do not appear to explain all the recent rises in employment at older ages (e.g. in UK and US). Early re9rement and inac9vity by age and wealth quin9le UK: men Note: Wealth quinMles are defined within each five-­‐year age group. Source: Banks and Casanova (2003), based on sample of men from the 2002 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Taxable income…for top earners • Captures addi9onal avoidance and tax shiXing responses – the ‘elas9city’ can be expected to fall as the tax base broadens • For a given tax base we can get an idea of the Laffer rate, the revenue maximising top rate – 1/[1 + taxable income elas9city (e) * Pareto parameter (a)] Probability density (log scale) 0.0100 0.0010 Pareto distribution Actual income distribution 0.0001 0.0000 0.0000 £100,000 £150,000 £200,000 £250,000 £300,000 £350,000 £400,000 £450,000 £500,000 – ‘a’ around 1.67 and ‘e’ around .45 for UK; Mirrlees (2011). – ‘e’ reliable?, Ignore a variety of dynamic and structural issues. Some key messages emerge for reform: • First, it is important to take a‘life9me’view – key points in the working life where tax incen9ves ma5er. • Second, must account for interac9ons between taxes and welfare – effec9ve tax rates depend on incen9ves in the welfare system, taxes on employers as much as in the personal tax system. • Third, fixed costs, informa9on costs and s9gma are important – responses at the extensive margin differ from intensive margin, – take-­‐up among eligibles is costly. • Fourth, accoun9ng for human capital investment ma5ers – educa9onal investments enhance human capital at work, – incen9ves for educa9onal investments influenced by taxes. • Finally, taxable income captures avoidance/shiXing opportuni9es. Evidence since the financial crisis suggests • In general workers and families are ac9ng as if they expect a long-­‐run fall in rela9ve living standards – evidence from consump9on and saving; and responses in labour supply. • Capital investment and/or produc9vity have been slow to pick up – employment for the young/low skilled may bounce back, but what of real wages and produc9vity? • Appears the number of rou9ne jobs near the middle of the earnings distribu9on has declined steadily, at least in the UK and US – more jobs are now professional or managerial. • Suggests longer term earnings growth will mostly come from high-­‐ skilled occupa9ons, with some at the very bo5om. • There remain the same key points where tax systems can be reformed to enhance earnings, employment and human capital. 80 © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies 2013Q1 2012Q3 2012Q1 2011Q3 2011Q1 2010Q3 2010Q1 2009Q3 2009Q1 2008Q3 2008Q1 2007Q3 2007Q1 2006Q3 2006Q1 2005Q3 2005Q1 Private consumpMon (2008Q1 = 100) Consump9on Growth 105 100 EU28 95 Spain 90 Italy 85 United Kingdom Non-­‐ (and semi) durables; UK recessions 120 Quarter before recession = 100 115 110 105 1980 1990 100 2008 95 90 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Quarters since start of recession © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Employment rate for older workers: women aged 60-64 45.0 40.0 35.0 Euro area (13 countries) 30.0 Germany (un9l 1990 former territory of the FRG) 25.0 Spain 20.0 France Italy 15.0 United Kingdom 10.0 5.0 0.0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Employment rate for older workers: men aged 65-­‐69 30.0 25.0 Euro area (13 countries) 20.0 Germany (un9l 1990 former territory of the FRG) Spain 15.0 France Italy 10.0 United Kingdom 5.0 0.0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Employment rate for older workers: men aged 60-64 70.0 60.0 Euro area (13 countries) 50.0 Germany (un9l 1990 former territory of the FRG) 40.0 Spain France 30.0 Italy 20.0 United Kingdom 10.0 0.0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 For the young employment fell back.... Employment rate: men aged 25-29 90.0 85.0 Euro area (13 countries) 80.0 Germany (un9l 1990 former territory of the FRG) Spain 75.0 France Italy 70.0 United Kingdom 65.0 60.0 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Employment shares of occupation groups: UK Note: the discontinuities in occupation classification in 2001 and 2011 have been addressed in the following way. For the conversion of SOC 1990 to SOC 2000, we look at individuals who were surveyed in 2000Q4 and 2001Q2 and stayed with the same employer and infer the transition matrix from this group. For the conversion of SOC2010 to SOC 2000, we used the ONS two-way tabulation of the LFS 2007 Q1 sample by the major occupation groups under the two SOC systems. © Ins9tute for Fiscal Studies Recent evidence suggests • In general workers and families are ac9ng as if they expect a long-­‐run fall in rela9ve living standards – evidence from consump9on and saving; responses in labour supply. • Produc9vity and capital investment have been slow to pick up – employment for the young/low skilled may bounce back, but what of real wages and produc9vity? • Appears the number of rou9ne jobs near the middle of the earnings distribu9on has declined steadily – more jobs are now professional or managerial. • Suggests longer term earnings growth will mostly come from high-­‐ skilled occupa9ons, with some at the very bo5om. • There remain the same key points where tax systems can be reformed that will also enhance earnings, employment and human capital. Prospects… • S9ll much to do in focussing on older workers in general, on return to work for parents/mothers, and on entry into work. • There are some poten9al big gains here, – for example, as (higher skilled) women age in the workforce. • Tax/welfare reforms to enhance earnings (from Mirrlees): – refocus incen9ves towards transi9on to work, return to work for lower skilled mothers and on enhancing incen9ves among older workers. • Human capital and ‘on the job’ wage/produc9vity complementarity – note the poten9al importance of mismatch of entry skills in this recession. • Produc9vity remains a key issue. 5. Some key messages emerge for reform: • First, it is important to take a‘life9me’view – key points in the working life where tax incen9ves ma5er. • Second, must account for interac9ons between taxes and welfare – effec9ve tax rates depend on incen9ves in the welfare system, taxes on employers as much as in the personal tax system. • Third, fixed costs, informa9on costs and s9gma are important – responses at the extensive margin differ from intensive margin, – take-­‐up among eligibles is costly. • Fourth, accoun9ng for human capital investment ma5ers – educa9onal investments enhance human capital at work, – incen9ves for educa9onal investments influenced by taxes. • Finally, taxable income captures avoidance/shiXing opportuni9es. Implications for efficient redesign of tax policy • Current systems remain unnecessarily complicated and induce too many people not to work or to work too li5le. • Target work incen9ves where they are most effec9ve – simula9ons in Mirrlees (2011) show key increase in work/earnings – reducing means-­‐tes9ng and improving the flows into work for lower educa9on mothers and maintaining work for those aged 55+. • Integrate overlapping benefits -­‐ a single integrated benefit – Mirrlees (2011) -­‐ ‘ifs’ and ‘universal credit’ reforms. • Reduce disincen9ves at key margins for the educated – enhancing working life9me and the career earnings profile – simula9ons in BDMS (2013) show significant effect on human capital. • Align tax rates at the margin across income sources