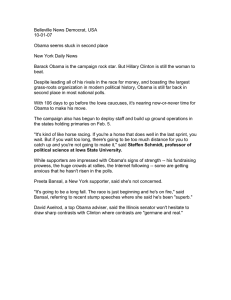

Using Group Consciousness Theories to Understand Hillary Clinton, and Ingo Hasselbach

advertisement