INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION CASE STUDY OF THE CHANGING INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ENVIRONMENT

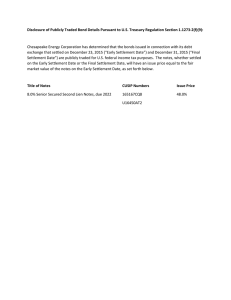

advertisement