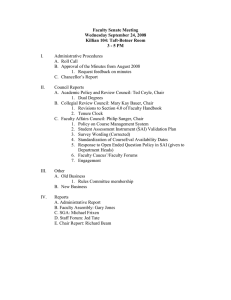

Population and Reproductive Health

advertisement