Population and Reproductive Health

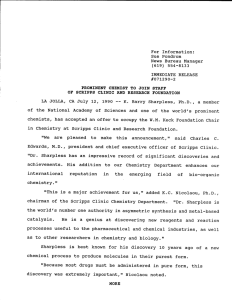

advertisement