{QTtext}{timescale:100}{font:Verdana}{size:20}{backColor:0,0,0} {textColor:65280,65280,65280}{width:320}{justify:center}

advertisement

{QTtext}{timescale:100}{font:Verdana}{size:20}{backColor:0,0,0}

{textColor:65280,65280,65280}{width:320}{justify:center}

{plain}

[00:00:00.506]

( Background noise )

[00:00:07.176]

>> Good afternoon, everyone.

[00:00:08.436]

Thanks for turning out on such

a beautiful early spring day.

[00:00:14.896]

We know this reflects your heart-felt

devotion to scientific inquiry.

[00:00:19.966]

And also that some of you were required

to be here, but that's just a small thing.

[00:00:23.686]

My name is Pat Thomas, and I teach health

and medical journalism to Graduate Students

[00:00:28.896]

at the Grady College of Journalism

and Mass Communication.

[00:00:32.026]

And this is the fourth year in a row that

I've been fortunate enough to be able

[00:00:36.046]

to co-organization and co-sponsor Voices

From the Vanguard series in collaboration

[00:00:41.966]

with Dan Colley and the Center For

Emerging Global and Tropical Diseases.

[00:00:46.736]

You know, we have really felt that the purpose

of this series was to bring the world to you,

[00:00:51.666]

I mean, here we are in Athens, Georgia,

and we have been able to bring speakers

[00:00:55.856]

from California, New York Washington,

Boston, even Geneva, Switzerland.

[00:01:01.516]

But you know, there's a lot of the world

that exists in Athens, Georgia as well.

[00:01:06.616]

And although we've never before features

UGA professor, which was a first.

[00:01:12.516]

And as you can imagine since Dan Colley is the

co-organizer of this series it was really hard

[00:01:17.636]

to get him to agree to also be a featured

speaker, but I'm really glad that he did.

[00:01:21.316]

And I'm going to now -- just one

more note I'd like to mention.

[00:01:25.306]

After Dan's no doubt fabulous talk we'll be

moving next door to Dellstanian Hall (Phonetic)

[00:01:32.026]

where as one of my students

says we have the best food

[00:01:35.586]

of any reception that you find on campus.

[00:01:38.246]

So come over, talk to the speaker,

hang out with us for a little while.

[00:01:43.156]

That's immediately following the talk.

[00:01:45.276]

So now I'm just going to welcome

another of my favorite people,

[00:01:48.106]

vice president for research David Lee,

who's going to introduce our speaker.

[00:01:52.586]

[00:01:54.356]

>> David Lee: Well, I made it up the stairs

with no mishap, so that's the good news.

[00:02:06.076]

Actually had to race back here

from Atlanta, had to give a talk

[00:02:09.016]

at the board of regents meeting today.

[00:02:11.726]

But it was important to me to be here.

[00:02:14.106]

Not just to introduce today's speaker,

Dan Colley, although I will do that,

[00:02:20.496]

but also because I really wanted to have

the chance to behalf of the university

[00:02:25.236]

to thank both Dan and Pat for organizing

what I think has been a wonderful series

[00:02:32.626]

over multiple years now.

[00:02:35.166]

It's important, this series, not only because

it exposes students to some of what -[00:02:43.236]

some of the cutting-edge work that's

going on in the area of global diseases,

[00:02:47.026]

infectious diseases, but I think

more importantly than that,

[00:02:52.356]

it really has been a great -- each of

those stories has been a great lesson

[00:02:57.876]

in what a single individual can do to change

the lives of a lot of people around the world,

[00:03:06.876]

given the vision, given the energy and so on.

[00:03:09.796]

And really much as anything, that's

what I've gotten out of these lectures.

[00:03:14.186]

And whether that's helping develop or taking

the lead in developing new malaria vaccine

[00:03:20.246]

as we heard about most recently, or

whether it was starting a foundation

[00:03:24.396]

that is making a difference in terms of

getting people to focus on neglected diseases.

[00:03:29.726]

I think there have been some really

wonderful stories here and I hope -[00:03:33.446]

I hope students have been able to enjoy that.

[00:03:35.876]

I can't think of a more important thing for

a university to do that to provide students

[00:03:41.706]

with those kinds of life examples.

[00:03:44.326]

Okay, so now I'm going to introduce

today's speaker, Dan Colley.

[00:03:48.996]

Dan is one of these guys who's managed

to make a living spending time in some

[00:03:55.506]

of the greatest places on Earth,

and I really hate him for that.

[00:04:00.626]

But maybe that's a consequence of

having grown up in Buffalo, New York.

[00:04:06.246]

Just felt the urge to get away.

[00:04:08.286]

And in fact, as soon as dad

hit 17 he headed south.

[00:04:12.626]

First stop was -- actually,

where was the first stop?

[00:04:18.456]

( Laughter )

[00:04:18.936]

>> Oh, Center College, how could I forget.

[00:04:21.046]

You have that in common with our president.

[00:04:23.106]

Got your -- Dan got his bachelor's

degree at Center College, Kentucky.

[00:04:29.156]

And then headed further south to

Tulane, where he obtained a Ph.D.

[00:04:34.726]

And I think there Dan really trained

as a fundamental immunologist.

[00:04:40.146]

He then made a mistake.

[00:04:42.916]

He headed back north, went

to Yale for a post-doc.

[00:04:47.396]

Didn't last two years up in

the bitter cold of New Haven.

[00:04:50.986]

Decided to make a terrible mistake,

[00:04:53.836]

and this time he headed south

and he didn't know when to stop.

[00:04:57.146]

So he ended up in Brazil.

[00:04:59.316]

And there he spent the better part of a

year, and Dan I might get this story wrong

[00:05:04.316]

because I haven't had a chance

to check it with you.

[00:05:06.116]

But I think you ended up working with some

of the Brazilian federal research entities

[00:05:12.596]

out in the field, so to speak,

working on tropical diseases.

[00:05:18.216]

And it's there where Dan's life-long

love of schistosomiasis really developed.

[00:05:26.386]

And as Pat Thomas would point out, it

was really a fundamental reinventing

[00:05:31.146]

of Dan Colley at this point.

[00:05:33.616]

From fundamental immunologist to

immunologist who was really concerned with how

[00:05:38.256]

to attack a tragic disease that takes a

huge toll on a very large number of people.

[00:05:44.516]

So Dan Colley Version 2, as Pat would

describe, then came back to the states and ended

[00:05:53.306]

up at Vanderbilt as an assistant professor.

[00:05:56.676]

Established his research program,

got NIH funding, did all the things

[00:06:03.106]

that a good professor should do,

working hard to attack this disease.

[00:06:09.406]

Somewhere along the way, and I'm not -maybe we'll clarify this this afternoon,

[00:06:14.536]

Dan decided to go to the Center

For Disease Control and Prevention,

[00:06:18.676]

and he spent nine years there directing

their parasitic diseases group.

[00:06:25.276]

At that point he decided that he wanted to

come back to the university to academia.

[00:06:30.926]

Fortunately, the University of Georgia had

a position, and it was to direct the Center

[00:06:36.736]

For Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases that

Rick Carlton had started a number of years ago.

[00:06:43.896]

So it's a great story.

[00:06:45.096]

We're going to hear a lot more about

it tonight, and I'm looking forward

[00:06:50.326]

to hearing Dan's first-hand stories of how

he got so interested in schistosomiasis.

[00:06:54.586]

Dan, it's a pleasure to produce you.

[00:06:58.516]

( Applause )

[00:07:04.966]

>> I'm supposed to put this on?

[00:07:09.166]

Let me get set up here.

[00:07:14.186]

Thank you very much, David.

[00:07:15.586]

Most of that was true.

[00:07:19.396]

My mother might not recognize some of it, but -[00:07:25.736]

I'd like to start by thanking

the organizers for inviting me.

[00:07:29.396]

( Laughter )

[00:07:31.976]

>> Now this is -- this is a real

honor to be able to speak at home.

[00:07:37.396]

I have no jet lack from doing this.

[00:07:40.356]

This is really great.

[00:07:42.796]

So I would like to first start by doing a little

advertisement about the Center For Tropical

[00:07:50.116]

and Emerging Global Diseases, which some

of you know about, many of you know about.

[00:07:56.916]

But some of you don't.

[00:07:57.996]

And this is the kind of thing that I do at

the start of seminars when I go someplace.

[00:08:03.546]

What we have here at UGA is a

center, an interdisciplinary center

[00:08:08.576]

that has 19 faculty members, or will

when Don Harden gets here in March.

[00:08:15.266]

And the mission is very clear.

[00:08:18.506]

It's to pursue cutting-edge research on

tropical and emerging global diseases

[00:08:23.106]

and train students in this field.

[00:08:25.186]

And we have a number of goals.

[00:08:27.956]

We want to become and remain a preeminent center

for research and education in parasitic diseases

[00:08:35.256]

and other global diseases, and turn research

into medical and public health interventions.

[00:08:42.116]

And to promote global research and

education here at UGA and in Georgia.

[00:08:48.196]

Now some of those goals are more

difficult to attain than others.

[00:08:52.146]

The middle one is really hard.

[00:08:55.246]

Turning research into medical and public

health interventions is a challenge.

[00:08:59.496]

It's a long-term goal.

[00:09:01.586]

But what we do in the center

will take us that way

[00:09:04.906]

if that's the perspective

that we want to put on it.

[00:09:08.966]

We also have a training mission.

[00:09:11.336]

We have five training grants.

[00:09:13.286]

One is a standard NIHT 32 training grant,

and three of them are NIH training grants,

[00:09:21.796]

but they're D 43s from the Fogarty International

Center to train people in other places,

[00:09:28.596]

bring them to UGA, train them where

they are, let them get their degrees

[00:09:33.056]

and things in their home countries.

[00:09:35.486]

And we have one in Argentina,

one in Brazil, an one in Kenya.

[00:09:39.546]

And then we have an Ellison Medical

Foundation training grant that is travelling.

[00:09:45.406]

It is to send our students overseas and to

bring students from overseas labs to ours.

[00:09:51.496]

And we have six different principle

investigators out of the 19

[00:09:55.676]

that have overseas research, in place research.

[00:10:00.406]

Everyone else has their work here.

[00:10:03.246]

But these six have work here and elsewhere.

[00:10:06.806]

And this is just a list of the people.

[00:10:10.116]

And I'm not going to belabor

this, but I think it's important

[00:10:12.816]

to say it really is interdisciplinary.

[00:10:16.356]

We have people in the center from eight

different departments, which are listed here,

[00:10:21.746]

and four different colleges and schools.

[00:10:25.046]

And we come at these diseases

from many different perspectives.

[00:10:30.136]

And I think that's the strength of the center.

[00:10:33.036]

We don't all collaborate one with another,

[00:10:35.626]

we collaborate when it's

convenient and when there's a need.

[00:10:39.236]

But we do know there's somebody down the

hall or across campus that we can draw

[00:10:43.936]

on to get a different perspective

on our own research.

[00:10:47.066]

And I think that's really important.

[00:10:49.356]

So these are the diseases that are studied.

[00:10:53.456]

We have malaria, African

trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness.

[00:10:59.706]

Toxoplasmosis, cryptosporidiosis,

cyclosporiasis, shagus disease (Phonetic),

[00:11:05.506]

leishmaniasis, Cysticercosis, schistosomiasis,

lymphatic filariasis, if -- and vector biology.

[00:11:14.776]

Now it's a big list of long names.

[00:11:17.356]

But these are all problems someplace.

[00:11:19.446]

And many of them are actually

still problems in the U.S..

[00:11:22.996]

Some of them are on the bio

defense priority pathogens list,

[00:11:26.666]

some of them are major global health

problems, some of them are focal problems.

[00:11:31.966]

But I'm here to tell you,

you don't want any of them.

[00:11:35.806]

These are not things that you want.

[00:11:38.346]

So these are the kinds of things that we study.

[00:11:41.696]

Now, enough of the ad, we're

going on to schistosomiasis.

[00:11:46.136]

Now, schistosomiasis, as

you could tell by the title,

[00:11:51.206]

is a worm infection that

200 million people have.

[00:11:54.956]

That's a lot of people.

[00:11:57.246]

Now most of them are in Sub-Saharan Africa.

[00:12:01.996]

Some of them, about a million,

are in Asia, maybe 2 million.

[00:12:07.486]

And under a million probably

in South America by now.

[00:12:11.966]

So this is largely a Sub-Saharan

African problem, but not only.

[00:12:16.346]

The worms actually live in the blood vessels.

[00:12:20.046]

So we've heard some lectures

and we'll hear some more

[00:12:23.496]

about soil transmitted helminths

(Phonetic) that live in the gut.

[00:12:27.076]

That's outside the body.

[00:12:29.026]

Come on, that's not a real worm.

[00:12:30.986]

These live inside your body,

in your blood vessels.

[00:12:35.556]

And they live there for a very long time.

[00:12:38.046]

And there's a male and a female,

and they mate, and they make eggs,

[00:12:41.266]

and therein lies most of

the problem we mentioned.

[00:12:45.146]

The global distribution depends on snails.

[00:12:49.596]

Certain snails.

[00:12:51.676]

Don't have the snails, you

don't have transmission.

[00:12:54.476]

But even to a great extent depends on

sanitation or the lack therefore thereof.

[00:12:59.966]

And that's a real problem.

[00:13:01.596]

Some day we won't have this

problem if we have sanitation.

[00:13:05.856]

It's a chronic infection, so these worms can

live in your blood vessels for up to 40 years.

[00:13:10.816]

You know, 40 years.

[00:13:13.766]

The mean life span is probably

more like 7 to 10,

[00:13:17.596]

but they can live for 40

years in your blood vessels.

[00:13:21.196]

[00:13:22.286]

Untreated, 5, maybe 10% of the people who

have it go on to very severe disease and die.

[00:13:30.866]

And they die of messing up your liver, mainly.

[00:13:34.316]

And the blood flow back through

the liver doesn't work,

[00:13:37.166]

and you end up with esophageal

varices, and you bleed out.

[00:13:42.246]

The other 90 to 95% have what's called subtle

morbidity, and we'll mention that in a minute.

[00:13:49.216]

So there's a good drug more

schistosomiasis, it's called Praziquantal.

[00:13:54.046]

It's available, it's not free, like some of the

drugs, to treat neglected tropical diseases,

[00:14:00.466]

but some groups are working on that.

[00:14:02.676]

And Praziquantal is a good drug.

[00:14:04.506]

It cures you.

[00:14:05.856]

The problem in the real world is people

get it again, an again, an again.

[00:14:11.586]

There's no vaccine.

[00:14:13.346]

So we're stuck only with a drug.

[00:14:16.896]

So this is the life cycle,

and it's also the evidence

[00:14:19.446]

for why I'm a scientist and not an artist.

[00:14:22.126]

But if you look at this, it's -- this

life cycle -- I can't -- let's see here.

[00:14:29.926]

See if I can get the pointer to work.

[00:14:31.476]

No, okay. The adult worms, the

pink and blue ones up there,

[00:14:35.456]

the males and the females,

live in the blood vessels.

[00:14:38.456]

And they make eggs.

[00:14:39.896]

And there are three main

species that infect people,

[00:14:42.626]

and those eggs are meant to portray those.

[00:14:46.236]

The eggs have to get out of the

body or there's no life cycle.

[00:14:51.306]

So the eggs get out of the

body in feces or urine,

[00:14:55.136]

depending on the strain,

the species of schistosomes.

[00:14:59.996]

When they hit the water, they have to get to

fresh water, inside, the little embryo hatches

[00:15:05.806]

out of the egg and swims

around looking for a snail.

[00:15:10.026]

Not any old snail, has to be -- not

that snail, a specific kind of snail.

[00:15:16.396]

Each one has a different set of snails.

[00:15:19.196]

Then we reproduce in there asexually.

[00:15:22.376]

So out of one of these mericia (Phonetic) going

[00:15:25.266]

into a snail you might get

10,000 of the next stage.

[00:15:28.906]

This is the mutilative stage.

[00:15:32.016]

So 10,000 of these little

wiggly guys come out over here

[00:15:35.826]

on the left, and they're looking for us.

[00:15:38.936]

They want to penetrate through our skin, we

don't know it, they have a bunch of enzymes

[00:15:43.766]

that help them get through the skin.

[00:15:45.506]

They come in and they migrate around, and

over about five or six weeks they mature

[00:15:50.996]

to adult worms, and you have

the whole thing over again.

[00:15:55.176]

So that's the life cycle.

[00:15:56.856]

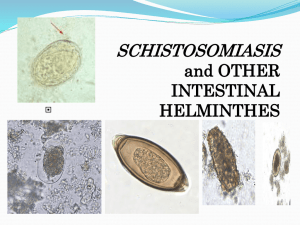

And this is what it looks like in pictures.

[00:16:02.306]

So you have adult worms up there at the top.

[00:16:05.336]

They're making eggs over on the right-hand side.

[00:16:09.156]

What's down below I'll show you in a minute.

[00:16:11.476]

But the eggs get out.

[00:16:13.266]

They hatch.

[00:16:13.896]

The miracidium go out looking for a snail.

[00:16:16.306]

Turns into 10,000 of the infectious

stage, and around you go again.

[00:16:21.596]

[00:16:22.996]

So this is what the adult male

and female worms look like.

[00:16:27.106]

They're not very big.

[00:16:28.486]

They can't be very big, they're

in your blood vessels.

[00:16:31.586]

So they're maybe about a half an

inch long and like a piece of thread.

[00:16:36.976]

And there's male -- let's go back here -[00:16:40.206]

there's the male -- this

is technically a flat worm.

[00:16:44.056]

So this flat worm curves up, the male curves

up and forms a groove, and the female fits

[00:16:50.626]

in that groove, and they sit there in your

blood vessels and mate and eat for life.

[00:16:55.886]

40 years. Tough life, right?

[00:16:58.156]

You know, stupid worm.

[00:16:59.726]

Anyway, so the male and the female

form this sort of mating pair.

[00:17:07.006]

And these are just different pictures that

either I've taken or stolen from people ,

[00:17:12.166]

and they show the worm out and

they show the worm in the body.

[00:17:16.126]

And they show it down here in the

left-hand corner is a blood vessel.

[00:17:20.446]

So you can have a lot of these worms.

[00:17:24.676]

Most people don't.

[00:17:26.196]

Up in the left-hand corner is a

picture of 1659 worms that came

[00:17:32.316]

out of a Brazilian 18-year-old boy.

[00:17:34.956]

Because I counted them.

[00:17:36.216]

So I know.

[00:17:36.786]

And a medical student counted them back in 1970.

[00:17:40.726]

So that's a lot of worms.

[00:17:43.106]

Most people don't have that many worms, but we

don't really know how many most people have.

[00:17:49.396]

So this is the situation in

terms of morbidity and mortality.

[00:17:55.926]

Morbidity is when you get sick

and mortality is when you die.

[00:17:59.536]

200 million people infected in the world.

[00:18:02.406]

About 20 million of them, remember

I said 5 to 10%, so we'll say 10%,

[00:18:07.876]

have what's considered severe disease.

[00:18:10.736]

About 100 million have moderate morbidity, or

what's these days being called subtle morbidity.

[00:18:17.816]

Now I maintain that moderate morbidity

is something that someone else has.

[00:18:23.166]

Not you. We don't know how bad this

is, but we do know it's not good.

[00:18:28.046]

And it impedes learning capabilities,

it impedes growth, it has -[00:18:33.596]

you lose a lot of blood in

your urine, things like that.

[00:18:37.856]

And then maybe -- maybe as many as 80

million really don't have any consequences.

[00:18:44.216]

But we don't know how severe those might be.

[00:18:48.106]

If, you know, maybe there's a gradation there.

[00:18:50.926]

So this is what the culprit is.

[00:18:55.436]

So how do you get sick from schistosomiasis?

[00:18:57.456]

You get sick because some of those eggs that

the worm pair makes don't get out of the body.

[00:19:03.566]

They get swept by the blood to your liver.

[00:19:07.226]

And they impact in the liver,

because they're too big to go

[00:19:09.776]

through the presinusoidal

(Phonetic) capillaries.

[00:19:11.906]

So they're stuck in the liver, and your

body says wait a minute, that's not me.

[00:19:17.306]

That's foreign.

[00:19:18.796]

Now why they didn't say that about

the worms is a good question.

[00:19:21.626]

But they say that about the eggs.

[00:19:24.036]

So your body responds and

makes this great big lesion

[00:19:27.706]

up here called a granuloma

around the eggs in your liver.

[00:19:31.546]

And eventually in some people, they go

[00:19:35.216]

on to form what's called peri-portal

fibrosis in the right-hand picture.

[00:19:40.266]

Now what's wrong with that liver?

[00:19:42.656]

It's not in somebody.

[00:19:46.846]

They had to kill -- somebody

had to die to get that.

[00:19:49.086]

And they died because schistosomiasis over is a

long period of time built up a lot of fibrosis

[00:19:57.466]

around the vessels in your liver, and your

blood can't get back up to your heart.

[00:20:03.326]

So that's the real problem.

[00:20:05.176]

It's the response of your own body against

the products of the worm, the eggs.

[00:20:13.776]

So this is an ultrasound picture of somebody

with just beginning peri portal fibrosis.

[00:20:20.146]

And you can see the little -- sort of

donut-like shapes up there and down below here,

[00:20:25.916]

a little bit of banding on the right.

[00:20:28.246]

It's not so bad.

[00:20:30.546]

But it will get worse of the and

it will end up looking like this,

[00:20:35.056]

and your whole liver is blocked off

in terms of returning blood flow,

[00:20:39.026]

and that's the worst scenario in schisto.

[00:20:42.656]

There's another kind of schisto that

doesn't effect your liver so much

[00:20:47.106]

but events your bladder and

your uri-genital tract.

[00:20:50.446]

And if you look at the -- up on

the right-hand side we have a very,

[00:20:56.266]

very old picture that was

taken -- it's simply an x-ray.

[00:21:00.216]

There was no material injected into this person.

[00:21:03.216]

And yet you can see the outline of the bladder.

[00:21:06.306]

That big, almost sort of circular thing.

[00:21:09.696]

If your bladder is calcified like that

[00:21:11.996]

because you have schisto eggs

in it, it doesn't contract.

[00:21:15.726]

Bladders are supposed to go

down and up, down and up.

[00:21:20.496]

This just sits there.

[00:21:22.256]

Which means you have a really bad problem.

[00:21:24.896]

So the three main species are hematobium

(Phonetic), which is what causes this.

[00:21:29.236]

Japonicum (Phonetic), and mansani (Phonetic).

[00:21:31.006]

And they can cause a lot of trouble.

[00:21:34.106]

But this is what it really

looks like in the field.

[00:21:38.026]

What you see in the upper left is

a young man in Cairo who has -[00:21:45.186]

had systemic schistosomiasis, the worst form.

[00:21:48.186]

But what you see on the right lower part is a

picture of kids in a village outside of Cairo

[00:21:56.096]

where the prevalence of schistosomiasis

is about 70%.

[00:22:00.136]

Certainly in this age group, except for that

jerk over there that got in the picture.

[00:22:04.176]

But in this age group it's

basically a 70% prevalence.

[00:22:08.806]

So 70% of those kids have schistosomiasis.

[00:22:12.256]

And one of them is going to get sick

like this kid if we don't treat them.

[00:22:17.256]

I'm not going to spend any time on this,

[00:22:23.236]

but I think it's important to

talk about subtle morbidity.

[00:22:27.546]

There's a guy named Charlie King (Assumed

spelling) who's done a number of studies.

[00:22:30.676]

One of them has really shaken the

schistosomiasis world called Meta Analysis,

[00:22:35.856]

where you bring together hundreds and hundreds

of papers and try to analyze them all together.

[00:22:40.456]

And what Charlie did, and his colleagues did,

was go through all the literature looking

[00:22:48.096]

for measuring, in this case, hemoglobin

in people with schistosomiasis.

[00:22:54.916]

And the -- what you get out of a meta

analysis is called a forest plot.

[00:23:00.016]

And if things are on the left-hand side

of that vertical line, that's not so good.

[00:23:05.306]

And what he found was that people

[00:23:07.416]

with schistosomiasis had

significantly less hemoglobin

[00:23:11.686]

in their blood than did non-infected people.

[00:23:15.506]

Now people where they have schistosomiasis

have a lot of other things too.

[00:23:21.526]

So maybe this wasn't all due to schistosomiasis.

[00:23:25.346]

So the other thing they did was they looked for

other papers, and there weren't nearly as many

[00:23:29.836]

of them, but other papers where they

looked at the change in hemoglobin

[00:23:33.996]

after you treat with Praziquantel.

[00:23:36.616]

And praziquantel will only cure schistosomiasis

and one or two other worms, but not malaria,

[00:23:42.906]

not other things that cause hemoglobin loss.

[00:23:45.986]

And what they found is afterwards you

moved things over to the right-hand side

[00:23:49.886]

of this forest plot, which is good.

[00:23:53.026]

So they came up with this kind of

evidence from a meta analysis that says

[00:23:58.016]

that schisto really has perhaps even a broader

public health impact than the serious disease.

[00:24:05.746]

Now if you have the serious

disease and you're going to die,

[00:24:08.286]

you don't care about the population.

[00:24:10.276]

But if you're talking about public health

the main impact may be this subtle morbidity,

[00:24:15.556]

not just the 5% or so that die.

[00:24:20.526]

So we still have to diagnosis schisto by looking

in the stool and doing -- looking in the urine.

[00:24:27.246]

But these are the eggs.

[00:24:28.646]

The one with the sort of funny-looking spine

on the side is an S-mansonite (Phonetic) egg,

[00:24:33.806]

and the one with the turned-out

spine is hematobium.

[00:24:38.156]

So this is kind of messy.

[00:24:39.716]

This keeps most people out of parasitology.

[00:24:42.466]

I don't know why it didn't keep me out, but

you know, you can make your own conclusions.

[00:24:46.996]

I did toilet train normally,

but -- this is where you get it.

[00:24:54.046]

You get it where it's blue and where

it's green and where it's yellow.

[00:24:59.796]

And one interesting sort of

side fact from this map is

[00:25:05.016]

that in the new world we didn't have

schistosomiasis until the slave trade.

[00:25:09.956]

S-mansonite and hematobium both live in Africa.

[00:25:16.086]

Both came over on the slave trade, but only

one of them established in the new world.

[00:25:21.886]

Only S mansonite.

[00:25:23.116]

There's no hematobium in the new world.

[00:25:25.306]

Came over with the slaves, didn't last.

[00:25:28.206]

Why? We don't have that snail.

[00:25:32.636]

It's snail-specific.

[00:25:34.176]

We have the snails in Brazil

and Venezuela and Puerto Rico

[00:25:38.026]

that can transmit S mansonite,

they just happen to be there.

[00:25:42.846]

But we don't have the right

species to transmit hematobium.

[00:25:46.856]

So it didn't make it.

[00:25:49.476]

So here I am telling you about

the snails, and you know,

[00:25:56.616]

this shows you all the different

kinds of snails.

[00:25:59.996]

Now isn't that really interesting?

[00:26:01.816]

However, I have a friend here who

said wait a minute, wait a minute,

[00:26:06.686]

I -- this is a disease of snails.

[00:26:10.686]

Well, Suzy Sudanica here is right.

[00:26:13.736]

This is a disease of snails!

[00:26:17.986]

They get sick too.

[00:26:19.636]

So I think it's important

that Suzy gets her due.

[00:26:23.806]

So we do have something on here that

says this is also a disease of snails.

[00:26:29.326]

Suzy wouldn't let me get by without saying that.

[00:26:33.626]

So what -- why do you get schistosomiasis?

[00:26:37.116]

Well, we know why Suzy does,

it's the same reason we do.

[00:26:41.026]

Somebody poops in the pond or pees in the pond.

[00:26:45.146]

And you have human, and with one of

the species you have animal reservoirs.

[00:26:52.626]

Water is essential.

[00:26:54.616]

Has to have water.

[00:26:56.326]

You have to have fresh water.

[00:26:57.666]

You have to have fresh water because

that's where these snails live.

[00:27:00.906]

Not this one, but most of these snails.

[00:27:03.206]

You have to have the right snail host,

they have to have some place to live,

[00:27:08.236]

it has to be someplace that

people defecate or urinate.

[00:27:13.306]

Adult worms.

[00:27:16.236]

Adult worms contribute because

they make the eggs.

[00:27:18.676]

And they make the eggs for a very long time.

[00:27:22.736]

So if you're talking about a chronic infection,

you have lots of chances for transmission.

[00:27:28.136]

And that's important.

[00:27:30.236]

But it's a very focal disease.

[00:27:32.226]

So one village may have 60%

prevalence, and down the road 30% or 5%.

[00:27:38.996]

So it's really hard to map out where

you have to go to treat everything.

[00:27:44.526]

So the transmission dynamics look like this.

[00:27:47.126]

You have water, you have

snails, you have people.

[00:27:51.266]

You have people contaminating the

water and people contacting the water.

[00:27:55.486]

You have to have both.

[00:27:57.706]

And when you do in that little

intersection you get great transmission.

[00:28:03.156]

It sounds a little tenuous, but I'm here to

tell you it works really well in the field.

[00:28:08.956]

So how would you attack this?

[00:28:11.686]

Well, sanitation and water and health education.

[00:28:16.486]

That's a good idea.

[00:28:17.956]

It probably doesn't work very well if

you don't give people alternatives.

[00:28:23.156]

The sanitation has to be there or

the clean water has to be there.

[00:28:26.636]

Snail control can work, but the things we poison

snails with also kill fish and other stuff,

[00:28:32.816]

and they wash out, and they're very expensive.

[00:28:36.516]

Hemo therapy is the current control.

[00:28:40.566]

And that means drugs.

[00:28:42.236]

Praziquantal.

[00:28:43.686]

So the current control isn't to stop

transmission, it is to stop people being sick.

[00:28:50.366]

If you give Praziquantal about

once a year to children in school,

[00:28:56.296]

they don't get sick from schistosomiasis.

[00:28:58.746]

Their subtle morbidity is lower,

although it's hard to measure that.

[00:29:04.206]

[00:29:05.576]

So we'll come back to public

health control part in a minute.

[00:29:08.496]

First we're going to just

mention some of the research.

[00:29:11.336]

So as an immunologist there are lots of

fascinating parts about schistosomiasis.

[00:29:15.666]

Lots. This host-parasite relationship has

developed over a very, very long time.

[00:29:21.786]

And I think it's a large amount of hubris for us

to think that we're just going to interrupt it.

[00:29:26.486]

But even if it wasn't a bad disease, which it

is, it would be interesting to an immunologist.

[00:29:34.436]

So what are the major basic bio-medical

research questions about human schistosomiasis?

[00:29:40.626]

Well, we'd like to know what correlates

and what the mechanisms are to resistance.

[00:29:45.896]

There is some resistance, and I

would say show you a little of that.

[00:29:49.156]

What are the correlates and

mechanisms of subtle morbidity.

[00:29:51.966]

We're not sure how to measure it.

[00:29:54.996]

What are the correlates and

mechanisms of severe morbidity.

[00:29:57.846]

Why do 5% get sick and die

and everybody else doesn't.

[00:30:02.246]

We don't know that.

[00:30:03.876]

Does schistosomiasis prevent auto

immune diseases and atopic allergy?

[00:30:08.816]

Well, there's some evidence that that's so.

[00:30:11.376]

Now does that mean everybody ought

to go out and get schistosomiasis?

[00:30:14.786]

No, it means basic scientists ought to

figure out why, and then be able to apply it

[00:30:19.746]

to auto immune diseases and allergies.

[00:30:22.056]

Transplantation.

[00:30:23.736]

If that worm that lives for 40 years, if I could

do that with a kidney, I'd be rich and famous.

[00:30:30.906]

How does it stay in there?

[00:30:32.206]

We don't know that.

[00:30:33.946]

So asking those sorts of questions

in schistosomiasis can shed light

[00:30:38.376]

in other areas of bio-medical research.

[00:30:42.336]

[00:30:44.466]

So what's our lab's current research?

[00:30:47.956]

Well, it takes place in Kenya.

[00:30:50.046]

And we work with a group called Sand Harvesters,

[00:30:54.776]

and another group called Car

Washers and then children in school.

[00:30:58.986]

So these are the three groups.

[00:31:01.436]

The car washers wash cars.

[00:31:04.176]

Well, big deal.

[00:31:06.116]

Down at the car wash -- no, in Tasuma

(Phonetic) that's lake Victoria.

[00:31:12.886]

So they drive the cars into Lake Victoria, in

this case most of them are trucks and vans,

[00:31:17.986]

they drive them in, then they

slosh them down with water.

[00:31:20.326]

And they're standing in the water the whole

time, which is how you get schistosomiasis.

[00:31:26.466]

The sand harvesters are even more exposed.

[00:31:29.066]

They're standing chest-deep with a shovel,

harvesting sand off the bottom of the lake

[00:31:33.676]

into their boat, pull the boat over

to the shore, empty it out by standing

[00:31:37.506]

in the lake and shovelling it on to shore.

[00:31:39.936]

Haggle with somebody about the price,

and then load the dump truck up.

[00:31:44.966]

That's harvesting sand.

[00:31:47.166]

The kids are in school right there, but

they're also in the lake much of the time.

[00:31:52.906]

So Tasuma in the western part of

Kenya, my post-doc and technician -[00:31:58.256]

one of my technicians is there right now.

[00:32:00.666]

I'll be joining them -- I'll be there Saturday.

[00:32:04.716]

Leave Thursday.

[00:32:05.846]

Takes a long time to get to Tasuma.

[00:32:08.036]

So these are the people who

do most of the research.

[00:32:10.616]

We also have field teams -- large field

teams and laboratory teams in Kenya.

[00:32:17.996]

But here we have Carlo Black, Michael

Gallen, and Jen Carter (Assumed spellings)

[00:32:22.906]

who are post-doc gradate

student technician in the lab.

[00:32:27.016]

Evan Seccor is a collaborator left over from CDC

days, and Diana Kurangen and Paula Winsey are

[00:32:33.606]

on site all the time, fortunately,

because I'm not.

[00:32:38.216]

So the epidemiologic question

in the beginning was

[00:32:42.846]

if we treat this guy how long does

it take before he gets reinfected.

[00:32:46.936]

And you can only do that by longitudinal

studies, which have a whole different feel

[00:32:53.356]

to them than everything else I've ever done.

[00:32:56.696]

And what we found by treating these guys,

following them up by doing stool exams

[00:33:03.656]

about every four weeks to see when

they got eggs in their stool again.

[00:33:09.576]

So we did this for years and years, we've

been doing this for 14 years out there.

[00:33:13.266]

Some of these guys have worked

with us for 14 years.

[00:33:17.176]

And in the paper that we published a couple

of years ago, now six years ago in lancet,

[00:33:23.586]

what we found by following these guys

was a little bit surprising to us.

[00:33:28.916]

We found that the time it took for

them to get reinfected differed.

[00:33:33.376]

We thought everybody might be the same.

[00:33:35.366]

We hopped they weren't, but they

turned out not to be the same.

[00:33:39.106]

Some got reinfected quickly,

some got reinfected more slowly.

[00:33:42.986]

Took more cars, and we called them resistant.

[00:33:46.436]

And it was exciting, because the bottom

line here was that when we treated them

[00:33:53.956]

and retreated them because they got reinfected,

retreated them and retreated them, they got -[00:33:59.556]

some of them got more and more resistant.

[00:34:03.036]

And when you do a longitudinal study

[00:34:08.006]

in basic science areas what you find

may or may not ever repeat itself.

[00:34:14.566]

So you've worked five or

six years to get these data,

[00:34:17.366]

then you have to do it all

over again and see if it works.

[00:34:20.606]

Well, fortunately for us, it did.

[00:34:23.206]

And what this slide shows is that some

people have to wash a lot of cars,

[00:34:29.076]

over 450 cars before they get reinfected.

[00:34:31.586]

That's the red line at the top.

[00:34:33.536]

And some people get reinfected

after only about 300 cars.

[00:34:36.856]

And that's the blue line.

[00:34:38.836]

And the number of reinfections

is across the bottom.

[00:34:41.316]

That's a lot of reinfections and retreatments,

but if you do that, some of the people who start

[00:34:47.406]

out low slowly but surely become more resistant.

[00:34:52.986]

And for an immunologist, that's exciting.

[00:34:56.436]

So it did happen again.

[00:35:00.186]

We found what we found the first time.

[00:35:02.226]

And the hypothesis that we work on is that

killing worms is what induces resistance.

[00:35:10.486]

Just having worms doesn't seem to do it.

[00:35:13.366]

But having dying worms in

your blood vessels seems to.

[00:35:17.306]

At least that's what correlates with the data.

[00:35:18.986]

If that's a mechanism or not, we don't know.

[00:35:22.036]

So we proposed that on worm death,

multiple worm deaths over time,

[00:35:30.836]

you end up getting more resistant.

[00:35:33.276]

And we wanted to look at the immune

responses that correlate with that.

[00:35:37.396]

So how do we do this research?

[00:35:40.456]

Okay, you work with the people,

always have to work with people.

[00:35:44.646]

You explain what you're going to do.

[00:35:46.616]

You've already gotten IRB

approval and everything

[00:35:48.946]

for what you do, but that doesn't get it done.

[00:35:51.276]

You have to deal with people, and you have

to convince them to stick their arm out

[00:35:55.356]

and give you blood every once

in a while and to give you stool

[00:35:58.636]

and you may think, yeah, that's cheap.

[00:36:00.596]

It's not so easy.

[00:36:01.956]

So you have to work with people.

[00:36:05.126]

Get their consent, all of that stuff.

[00:36:09.316]

Then you diagnose them for schisto,

other worms, malaria, and HIV,

[00:36:13.996]

because they're all common there.

[00:36:16.446]

And if you don't understand what's going

[00:36:18.886]

on with those you don't know what's

going on with schistosomiasis.

[00:36:22.956]

Then you bleed them, take the

blood back to the laboratory.

[00:36:27.436]

So here we are, bleeding out by the car wash.

[00:36:31.296]

And then going back -- we have regular

laboratory with biological safety hoods,

[00:36:36.396]

you know, cabinets, the whole thing.

[00:36:40.226]

Deal with the blood carefully, because

30% of the car washers have HIV.

[00:36:45.436]

Deal with the blood, put

up cultures, do immunology.

[00:36:50.136]

That's what you do.

[00:36:51.626]

Then you get the data from those

cultures or whatever you're doing,

[00:36:54.526]

the phenotyping by flow cytometry or whatever.

[00:36:57.306]

And then you try to analyze it in

relationship to what you know about that patient

[00:37:02.416]

and what you know about that group of patients.

[00:37:05.016]

And the more you know about them

epidemiologically and background-wise,

[00:37:09.986]

the better you're going to be

able to interpret your numbers.

[00:37:13.066]

Because without that, you just got numbers.

[00:37:16.646]

And then you publish papers

and try to get more funding,

[00:37:20.886]

and each time you try to improve your question.

[00:37:24.506]

That's what this is about.

[00:37:26.666]

So I'm not going to spend any

time on the results of that.

[00:37:30.126]

Just that over the last six years we've been

publishing papers about things that seem

[00:37:37.116]

to correlate or don't correlate with

resistance, and we are still doing so.

[00:37:43.466]

That's why Kara and Hillary

are out there right now.

[00:37:47.326]

And why Jen is trying to figure out an assay.

[00:37:52.286]

Did she finish in time to get here?

[00:37:53.626]

I don't know.

[00:37:54.296]

Anyway, figure out an assay that I

will take out when I go on Thursday.

[00:38:00.256]

So you get all these correlates.

[00:38:02.226]

So what? Well, you publish

papers, you get grants.

[00:38:05.506]

Cool. But that's only part

of why you're doing this.

[00:38:09.666]

This is too much trouble to do just for that.

[00:38:13.316]

So that's a good question.

[00:38:14.806]

So what. What we hope is to learn enough

to form a composite of what is needed

[00:38:22.636]

to really give you substantial

protection against schistosomiasis.

[00:38:28.076]

Because those are the responses that we would

like to engender with a vaccine some day.

[00:38:33.936]

Just any old -- as you heard from Steve

Hoffman if you were here in January,

[00:38:39.326]

just any old response isn't what you want.

[00:38:41.996]

You want certain immune responses.

[00:38:43.946]

So we're trying to define what those immune

responses are that correlate with protection

[00:38:49.176]

so that you can go after those responses.

[00:38:52.556]

And also immunology, as I

said before, is immunology.

[00:38:55.646]

What we learn here are the same mechanisms

that are going on in any immunologic situation.

[00:39:02.216]

Infectious or otherwise.

[00:39:03.626]

And I think that's a very important point.

[00:39:08.216]

So the heart of our research in Kenya

is -- oh, goodness, not that one.

[00:39:13.686]

Yeah, there.

[00:39:14.696]

Transmission sites.

[00:39:16.606]

So we have the children, we

have the sand harvesters,

[00:39:21.106]

we have the car washers,

and we have the village.

[00:39:26.156]

This is what the village looks like.

[00:39:27.566]

Now we only study villages some,

because you can't control it as well.

[00:39:32.366]

You don't know the exposure like we do with

the car washers an the sand harvesters.

[00:39:36.446]

But you can see that the women

are down washing clothes.

[00:39:39.606]

This is what they do.

[00:39:40.936]

That lake has schistosomiasis and

they have the potential of getting it.

[00:39:46.446]

So now we'll put on a different

hat , not as a basic immunologist,

[00:39:51.616]

not as a basic immunologist

doing schistosomiasis,

[00:39:55.536]

but as a global health researcher.

[00:39:58.116]

And someone that's involved in the other end of

what I call the research to control spectrum.

[00:40:05.996]

Now this spectrum or -- we

hope it's a spectrum anyway -[00:40:11.816]

goes from basic research at the

bench all the way to intervention.

[00:40:17.126]

Or you could say bench to

bedside if you're talking medical.

[00:40:22.576]

But bench to intervention if

you're talking public health.

[00:40:25.456]

And what you have are several levels of what

people do to control these kinds of diseases.

[00:40:32.916]

You have control, which is

what we do for schistosomiasis,

[00:40:36.876]

and we're only controlling morbidity by

this annual treatment with Praziquantal.

[00:40:42.226]

You have elimination as a public health

problem, or in a given area completely.

[00:40:47.966]

You have -- and that's the infections.

[00:40:50.996]

Or you have eradication.

[00:40:53.116]

Now we've eradicated small pox.

[00:40:56.216]

We haven't yet eradicated

guinea worm, but we're close.

[00:41:00.956]

We haven't yet eradicated

polio, and it keeps jumping up

[00:41:07.156]

and biting us, but we're still working at it.

[00:41:09.916]

But in parasitic diseases (Inaudible)

is as close as we get to eradication.

[00:41:15.116]

Extinction is when it's gone.

[00:41:17.956]

Small pox is gone.

[00:41:19.426]

It's in a lab -- a couple

labs, hopefully securely.

[00:41:24.456]

So what you do public health wise depends a lot

on what you want to do, what you have the tools

[00:41:30.846]

to do, what you have the public will to do.

[00:41:34.216]

Conceptually, these are very different things,

[00:41:36.936]

and they often get mixed up,

but they're very different.

[00:41:39.916]

So guinea worm is an eradication program.

[00:41:43.296]

Onicacyasis (Phonetic) is a control program,

lymphatic filariasis, which you've heard

[00:41:48.546]

in this series about, is elimination.

[00:41:51.376]

Schistosomiasis is morbidity control, and

that's what we're going to talk about.

[00:41:56.846]

So a few years ago the world health assembly,

which is all the ministers of health from all

[00:42:02.736]

over the world, sat down

in Geneva and decide aid

[00:42:07.356]

that they would pass world health assembly

5419, which is a resolution on schistosomiasis

[00:42:14.726]

and soil transmitted helminths (Phonetic).

[00:42:17.946]

The burden of disease is huge.

[00:42:19.676]

For soil transmitted helminths

it's over a billion people.

[00:42:22.916]

Yeah I know, it's -- in 2009, a billion

doesn't sound like much any more.

[00:42:27.426]

We're talking hundreds of billions

here and there and everything else.

[00:42:30.346]

But 2 billion people is still a lot of people.

[00:42:33.886]

To do these things you really

have to have lots of partners.

[00:42:40.566]

That's probably one of the biggest hurdles.

[00:42:42.946]

But these partners all have to get along,

and they don't all have the same goals.

[00:42:46.736]

Well, they all have the same final answer goals.

[00:42:49.666]

They don't all have the same

reasons for doing it.

[00:42:52.516]

So it's difficult to put these things,

these resolutions, into action.

[00:43:00.146]

And one of the things that we'll talk

about in a minute is operational research.

[00:43:05.716]

Because there's still questions that you have,

even though you have an eradication program

[00:43:10.426]

or an elimination program or a control program,

there's still questions that we don't know

[00:43:15.096]

about that will help that program.

[00:43:19.306]

So this -- about six years ago the Gates

Foundation funded something called the

[00:43:26.036]

Schistosome Control Initiative, or SCI.

[00:43:29.076]

It operates out of Imperial College in London,

[00:43:32.166]

and over the years they have

had 40 or $50 million.

[00:43:37.646]

And what they do is they buy Praziquantal,

they donate that to ministries of health in six

[00:43:44.616]

or eight countries Sub-Saharan Africa.

[00:43:46.666]

And they help the ministry of health deliver it.

[00:43:50.326]

They figure out the organizational needs,

logistical needs, and they help get it done.

[00:43:56.026]

And they facilitated over 50 million

treatments with Praziquantal in that time.

[00:44:01.606]

So that's a lot of treatment.

[00:44:05.256]

And they've dewormed more people

for soil transmitted helminths,

[00:44:08.486]

which kind of goes along

with it, with albendazole.

[00:44:12.666]

So in the countries listed on the

bottom there are country-wide programs.

[00:44:19.226]

And they're in place and they're being shored

[00:44:21.856]

up by this enormous amount

of Gates and now USAID money.

[00:44:25.386]

And that's a good thing.

[00:44:28.496]

Because if we can do it, we should be doing it.

[00:44:31.166]

There are a lot of people

that benefit from this.

[00:44:34.286]

But the Gates Foundation has also

just funded a program here at UGA.

[00:44:39.106]

It's called the Schistosomiasis Consortium

For Operational Research and Evaluation.

[00:44:45.556]

Or SCORE! I left off the

exclamation points on the slide.

[00:44:50.626]

So this is a new program.

[00:44:54.676]

It's just starting.

[00:44:56.816]

It's hectically just starting.

[00:44:59.336]

But it's a consortium to

do operational research.

[00:45:03.806]

Now that's not basic science,

it's operational research.

[00:45:07.576]

It's defined, it's finding out

what control program managers

[00:45:13.366]

in the field need to know

to do their job better.

[00:45:15.936]

And their job right now is handing out pills.

[00:45:19.676]

So part of what SCORE will do will be try

to figure out better ways to hand out pills.

[00:45:26.336]

How we convince people to take these

pills if they don't think they're sick?

[00:45:30.546]

Well, that's a job.

[00:45:33.666]

So it will be run out of UGA but

it will involve investigators

[00:45:38.506]

from around the world through sub awards.

[00:45:40.756]

So there will be a lot of sub awards.

[00:45:44.016]

And I should mention that the president's

venture fund here at UGA gave me some money

[00:45:50.266]

to help me set this consortium in

motion before the Gates came through,

[00:45:54.416]

because that was a huge help.

[00:45:56.026]

Let you travel around and talk to people

rather than do everything by e-mail.

[00:46:02.666]

So SCORE. There were some

ground rules established

[00:46:06.306]

when the Gates called me and

asked if I would do this.

[00:46:09.676]

And they were really pretty

firm about their ground rules.

[00:46:13.366]

Operational research only.

[00:46:15.686]

You know, no amount of wheeling and

dealing with them would make me -[00:46:19.846]

allow me to study lymphocytes

jumping through hoops.

[00:46:23.016]

This is not what they do.

[00:46:24.826]

This is operational research.

[00:46:26.826]

Not basic science.

[00:46:30.086]

We're not supposed to deal with

estraponicum, which is the one in the far east.

[00:46:35.986]

I may have some people on my advisory

board who deal with estraponicum,

[00:46:39.796]

but that's not where the money's going.

[00:46:42.036]

There's no drug development, no vaccine studies,

[00:46:45.456]

and we're to work with existing

control programs.

[00:46:48.036]

Well that makes sense.

[00:46:49.516]

And we're also supposed to work as broadly

as possible with the schisto community,

[00:46:53.326]

which sounds really good until you try to do it.

[00:46:56.076]

Anyway, those are the parameters

that I was given.

[00:47:00.036]

Now all of this is in relationship to mass

drug administration, M D A, with Praziquantal.

[00:47:07.496]

So these will be collaborative studies,

they will be complimentary studies.

[00:47:13.016]

They will be done in relationship

one to another.

[00:47:16.836]

So the -- there are three in the Gates

terminology, there are three objectives.

[00:47:24.406]

Each one has a series of activities below it.

[00:47:28.106]

The first objective is to evaluate alternative

approaches to control schistosomiasis.

[00:47:34.656]

And to eliminate schistosomiasis in

settings with low or seasonal transmission.

[00:47:39.586]

Well, elimination is really, really hard.

[00:47:42.636]

So we'll see about that.

[00:47:44.246]

But the activities.

[00:47:47.106]

The first two activities actually go

together and we'll be having a meeting here

[00:47:51.046]

with about 25 people from

around the world in April to try

[00:47:55.956]

and get a handle to the existing data.

[00:47:58.596]

What do we know works or doesn't

work in control of schistosomiasis.

[00:48:03.276]

So these people are going to come together.

[00:48:05.556]

I sent the letter of invitation

out about two hours ago.

[00:48:10.176]

Third week of April, come together for three

days, and try to sort out what we already know,

[00:48:15.886]

so we don't start trying to reinvent that.

[00:48:20.026]

[00:48:21.336]

The next activity is how do you sustain control?

[00:48:25.826]

Okay, the schistosomiasis control initiative

did a great job in those six countries

[00:48:30.176]

and brought the prevalence way down.

[00:48:32.426]

If you leave and come back in five years,

it will be right back where it was.

[00:48:36.086]

We know that.

[00:48:37.346]

So how do you keep the slope

of return as low as possible

[00:48:42.066]

without spending $10 million every year.

[00:48:46.086]

So we'll be comparing different delivery

systems, and that will be research,

[00:48:50.436]

but it's very practical research.

[00:48:52.816]

The next one will be how do you

achieve real elimination in some place

[00:48:58.396]

that already has low transmission.

[00:49:00.576]

I call this the kitchen sink approach.

[00:49:04.036]

We'll throw everything at it.

[00:49:05.496]

We will do snail control, we will do

latrines, we will do lots of health education,

[00:49:11.056]

and we'll use drugs, and we'll

do everything we can think of.

[00:49:14.406]

Maybe reroute some water ways,

engineering kinds of things.

[00:49:18.416]

And the next one is even a bigger challenge

in that how do you for least amount

[00:49:26.226]

of money get prevalence load from starting

from someplace like that village in -[00:49:32.776]

outside of Cairo that I showed

you that had 70% prevalence.

[00:49:36.196]

How do you get it down, how

do you really get it down.

[00:49:39.546]

And we'll be doing that in relationship

to another series of questions

[00:49:43.526]

that are a bit more basic

science that I'll mention now.

[00:49:47.896]

Oh yeah, we'll also be doing

community health education

[00:49:50.806]

and cost (Inaudible) throughout all of this.

[00:49:53.056]

So the second objective is to develop

the tools needed for global effort

[00:49:58.036]

to control and eliminate schistosomiasis.

[00:50:01.066]

And we have a bunch of activities

that are more on the diagnostic side,

[00:50:05.696]

because we don't have good diagnostics.

[00:50:07.466]

We're still looking at stools, and it's 2009.

[00:50:11.216]

Now come on, we can do better than that.

[00:50:13.166]

So this money will fund some people

to try and do better than that.

[00:50:18.906]

For diagnostics in snails, I guess

Suzy Sudanica gets her day too.

[00:50:23.676]

And in people.

[00:50:25.026]

Because that's one way you

can monitor it in the snails.

[00:50:27.806]

And they're cute, too.

[00:50:30.266]

One of the things that we're going

to have a meeting on even before

[00:50:34.376]

that bigger meeting is we're going to have,

like, five people from around the world who look

[00:50:38.746]

at population structures of schistosomes by

micro satellites, et cetera, come together,

[00:50:43.796]

work out a unified protocol

-- I hear you chuckling -[00:50:47.426]

we will work out a unified protocol

because that's what we'll fund.

[00:50:52.286]

And then we'll be able to look

at the population structure

[00:50:54.956]

about which we know nothing at this point.

[00:50:57.886]

Under mass drug administration.

[00:51:00.106]

Mass drug administration, one

drug -- does this sound familiar?

[00:51:03.896]

Sounds bad.

[00:51:05.206]

Sounds like resistance.

[00:51:07.376]

So we don't know the mechanism

of Praziquantal action,

[00:51:11.316]

so we don't know what to

look for, for resistance.

[00:51:14.346]

But at least if we have a population structure

[00:51:17.116]

under study while we're doing mass drug

administration we may see some changes

[00:51:22.076]

in the genetics of the population that will

give us some clues that something's going on.

[00:51:26.916]

And then we're going to look at subtle

morbidity and try to come up with some outcomes

[00:51:31.476]

that are better than what we have.

[00:51:32.856]

And the third objective is

really simply to try and take -[00:51:37.176]

this won't kick in until like the third

year, where we try to take the findings

[00:51:41.316]

and actually move them into

guidelines at WHO and places like that.

[00:51:48.496]

So the management structure will be

-- there will be three components.

[00:51:52.276]

The sec tear Yacht, which will be myself,

consultant from Atlanta named Sue Binder,

[00:51:58.386]

Charlie King who is the guy who did

that meta analysis, associate director

[00:52:03.396]

for management, and an administrative assistant.

[00:52:06.596]

And then we'll have the technical

working group that will meet every year

[00:52:10.136]

to compare what we're finding, which will be

the 15 or 20 PIs of the various sub awards.

[00:52:16.106]

Then we'll have an advisory group

which I'm just now inviting.

[00:52:19.556]

So how is it going to work?

[00:52:23.476]

We're going to have these meetings, we're

going to select solicitations and proposals

[00:52:29.866]

to do the protocols that

come from those meetings.

[00:52:33.966]

Those will be awarded.

[00:52:34.986]

Then they have to get out the door,

then people will start doing something.

[00:52:41.646]

We'll have annual meetings to

compare what we're getting.

[00:52:45.196]

And it will be a lot of meetings,

that's what a consortium means.

[00:52:52.656]

So very quickly, global health

and global health research.

[00:52:55.626]

Do you know these public health workers?

[00:52:59.496]

Hmm. They're the best-known public

health workers in the world.

[00:53:04.976]

Bono and Bill Gates.

[00:53:07.946]

Global health has changed

enormously over the last ten years.

[00:53:12.426]

And a lot of it is because of these two guys.

[00:53:15.546]

And Melinda.

[00:53:16.486]

Don't leave Melinda Gates out.

[00:53:19.246]

So Senator Arlen Spector said when they

were looking at the FY 2008 budget,

[00:53:26.006]

a healthy world is a good thing for America.

[00:53:29.746]

Health diplomacy must be the

foundation of our foreign policy.

[00:53:34.556]

It's called winning hearts and minds.

[00:53:38.656]

It's called showing your best side.

[00:53:42.326]

So the question for the people in the

audience, especially the undergraduates

[00:53:46.346]

and graduate students and post-docs,

how do I get to work in global health?

[00:53:50.386]

Now I'm going to start by saying how

Dan Colley got to work in global health.

[00:53:56.286]

As David pointed out, I went to

high school in western New York.

[00:54:01.106]

I went to an even smaller

college in central Kentucky.

[00:54:05.376]

I married the right woman who would put

up with all this stuff when I was there.

[00:54:09.726]

Was worth the trip, folks, let me tell you.

[00:54:12.856]

Went to graduate school at

Tulane, in transplantation

[00:54:16.176]

and immunology, and microbiology.

[00:54:18.596]

They actually had a really

good tropical medicine group

[00:54:23.406]

at Tulane then, and I shunned those people.

[00:54:27.606]

They were the ones who dealt

with those yucky worms and stuff.

[00:54:30.606]

You know, they had display cases

full of horrible-looking things.

[00:54:35.766]

We stayed away from them as much as possible.

[00:54:37.546]

And then I went up to Yale and did my

post-doc in very basic science -- very basic.

[00:54:43.146]

I mean, this was before we knew a lot of stuff.

[00:54:47.686]

Then I took a kind of a wiggle,

and I went to Brazil.

[00:54:52.056]

I had this opportunity to go to Brazil

and teach a course in immunology

[00:54:56.636]

and reorganize some research that was going on.

[00:54:58.916]

And the research was in schistosomiasis.

[00:55:00.876]

And I couldn't spell it.

[00:55:02.856]

So I went anyway.

[00:55:04.526]

And I came back to a real job that

I rose through the academic ranks,

[00:55:10.496]

did all those things that

David said in Nashville.

[00:55:13.376]

And then I took another wiggle.

[00:55:16.716]

I'm not really sure why I

did this wiggle, but I did.

[00:55:19.316]

And I went to the CDC, and lo and behold

I was the director of the division

[00:55:24.396]

of parasitic diseases -- not ever having had

an epidemiology course or parasitology course.

[00:55:29.796]

He didn't ask.

[00:55:32.596]

It wasn't like I, you know, lied

to him on my resume, you know?

[00:55:35.816]

And then I came here, for

which I am very, very grateful.

[00:55:42.686]

Because it was time to leave CDC.

[00:55:44.556]

I learned a lot and I had done a lot, and

I was real pleased with my time there,

[00:55:47.926]

but I didn't want to end up there.

[00:55:50.086]

And so Rick Carlton made a

place for me here, and I came

[00:55:55.786]

and I've been living happily ever after.

[00:55:58.806]

So do you see a well thought out path here?

[00:56:04.146]

When someone comes in my office

and wants to know how they can work

[00:56:07.076]

in global health they always

want me to tell them a pathway.

[00:56:11.566]

Well, this one skipped around a bit.

[00:56:14.726]

I don't see a path here.

[00:56:18.326]

So how you get to work in public

health, in global public health.

[00:56:22.696]

What kinds of opportunities are there

for people like you in public health.

[00:56:29.746]

I beg you to remember the continuum, that

spectrum that I very strongly believe in,

[00:56:36.816]

but which is really hard to make happen.

[00:56:39.786]

The spectrum from bench to implementation

and intervention is fraught with problems.

[00:56:47.016]

Not very many people speak the whole language.

[00:56:50.296]

You don't have to speak the whole language.

[00:56:51.796]

You just have to be able to

speak the one over from you.

[00:56:55.076]

At least go out and have a beer with them, you

know, maybe you'll find they're interesting.

[00:57:00.116]

But remember the continuum.

[00:57:01.476]

Because there are things for people to

do all the way along that continuum.

[00:57:06.656]

Whether they're a health economist or a

journalist, even they do global health.

[00:57:14.306]

They actually do a lot for global health,

because without them nobody hears about it.

[00:57:18.906]

So you can do global health whether

you're a basic scientist or an MD,

[00:57:24.066]

or a public health official, or a publicist.

[00:57:28.556]

The whole continuum.

[00:57:32.196]

What education and training do

you need to work in global health?

[00:57:35.226]

It depends on which part

of that spectrum you want.

[00:57:37.986]

Now you may not know which part.

[00:57:39.756]

So cover your bases.

[00:57:41.246]

Now if you want to treat people -[00:57:43.576]

okay, if curing people is your

important thing you've got to get an MD.

[00:57:47.116]

It's against the law to do it if you don't.

[00:57:49.836]

I don't treat people.

[00:57:50.796]

I'm a Ph.D..

[00:57:52.606]

I give people pills to give to

people, but I don't treat people.

[00:57:57.276]

Okay? So if treating people is

important, you go to medical school.

[00:58:01.366]

You do your house staff training,

become a real physician.

[00:58:05.296]

Then you do a fellowship, and you do it in

anything but -- maybe infectious diseases,

[00:58:09.796]

maybe something else, maybe in pediatrics.

[00:58:12.976]

And then you do that research and

things that get you into that.

[00:58:18.436]

Now if you want to do research on global

health issues, you go to graduate school.

[00:58:23.386]

You can do research if you go to medical school.

[00:58:25.766]

No reason you can't.

[00:58:27.826]

But if you go to graduate

school you can't treat people.

[00:58:30.216]

So got to remember those things.

[00:58:32.686]

But you can go to graduate

school in almost anything

[00:58:35.886]

and end up doing global health

-- almost anything.

[00:58:38.996]

It doesn't have to be immunology like me.

[00:58:42.526]

Although I recommend that highly.

[00:58:46.126]

If you want to set policy, well, you

can be an MD, a Ph.D., have an MPH,

[00:58:52.296]

have just experience -- lots

of different things.

[00:58:55.836]

You can work at WHO, you can work at your -you know, at your local health department.

[00:59:00.696]

If you want to teach, depends

on what level you want to teach.

[00:59:04.796]

If you want to teach this stuff, fine.

[00:59:07.556]

We need people to teach this stuff.

[00:59:10.166]

So how do you want to make your

contribution to improving global health.

[00:59:15.206]

You just need to think about all the different

options, and there are a zillion of them.

[00:59:20.106]

So here in the Center For Tropical and Emerging

Global Diseases we try to turn research

[00:59:24.606]

into medical and public health interventions.

[00:59:26.646]

We try to promote global

and bio-medical research,

[00:59:30.106]

and our educational programs here at UGA.

[00:59:35.926]

We in CTG are doing global health.

[00:59:39.516]

And so are a lot of other people at UGA.

[00:59:42.856]

That's the nice thing about this.

[00:59:44.716]

That's actually what makes it fun.

[00:59:48.436]

Takes lots of people with

lots of different talents.

[00:59:51.806]

So (Inaudible) of schistosomiasis,

200 million people.

[00:59:55.566]

They can't be wrong, must be a real problem.

[00:59:57.706]

And it is.

[00:59:59.276]

They live in their blood vessels.

[01:00:01.676]

We can do something for them now.

[01:00:04.516]

We can give them Praziquantal.

[01:00:06.816]

If we just give them health

education, it doesn't help.

[01:00:09.816]

They know the life cycle at

the car wash better than I do.

[01:00:13.616]

They've been doing this for

14 years, some of them.

[01:00:15.356]

They know all about schistosomiasis.

[01:00:16.946]

But they don't have an alternative.

[01:00:19.166]

They wash cars in the lake because

unemployment in adult males in Tasumu is 40%.

[01:00:25.446]

And they have a job.

[01:00:28.326]

So they're going to go in that lake.

[01:00:30.106]

You have to give them an alternative, not

just tell them they shouldn't do that.

[01:00:36.346]

Research is needed, even

in eradication programs.

[01:00:40.426]

If you talk to Don Henderson,

the guy who was the head

[01:00:44.936]

of the global program that got rid of small pox.

[01:00:48.426]

He will tell you that during the

campaign there were findings from research

[01:00:53.226]

that helped them make the final run.

[01:00:56.246]

We need research.

[01:00:57.846]