GERDA LERNER Voices of Feminism Oral History Project

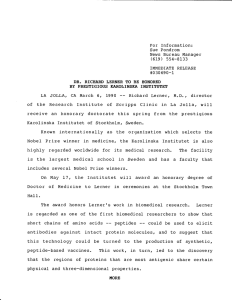

advertisement