Dimensions of Perfectionism in Relation to Academic Motivation and Statistics Anxiety Jennifer Chain, Jodi Jean, Jessie Katz , Patricia DiBartolo, Ph. D.— Smith College, Northampton, MA DISCUSSION ABSTRACT

advertisement

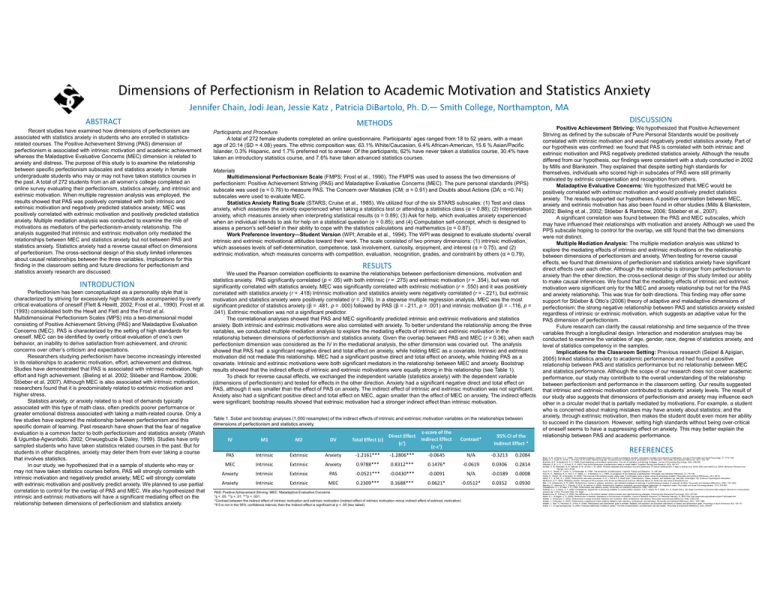

Dimensions of Perfectionism in Relation to Academic Motivation and Statistics Anxiety Jennifer Chain, Jodi Jean, Jessie Katz , Patricia DiBartolo, Ph. D.— Smith College, Northampton, MA ABSTRACT Recent studies have examined how dimensions of perfectionism are associated with statistics anxiety in students who are enrolled in statisticsrelated courses. The Positive Achievement Striving (PAS) dimension of perfectionism is associated with intrinsic motivation and academic achievement whereas the Maladaptive Evaluative Concerns (MEC) dimension is related to anxiety and distress. The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between specific perfectionism subscales and statistics anxiety in female undergraduate students who may or may not have taken statistics courses in the past. A total of 272 students from an all women’s college completed an online survey evaluating their perfectionism, statistics anxiety, and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. When multiple regression analysis was employed, the results showed that PAS was positively correlated with both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and negatively predicted statistics anxiety; MEC was positively correlated with extrinsic motivation and positively predicted statistics y Multiple p mediation analysis y was conducted to examine the role of anxiety. motivations as mediators of the perfectionism-anxiety relationship. The analysis suggested that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation only mediated the relationships between MEC and statistics anxiety but not between PAS and statistics anxiety. Statistics anxiety had a reverse causal effect on dimensions of perfectionism. The cross-sectional design of this study limited inferences about causal relationships between the three variables. Implications for this finding in the classroom setting and future directions for perfectionism and statistics anxiety research are discussed. INTRODUCTION Perfectionism has been conceptualized as a personality style that is characterized by striving for excessively high standards accompanied by overly critical evaluations of oneself (Flett & Hewitt, 2002; Frost et al., 1990). Frost et al. (1993) consolidated both the Hewit and Flett and the Frost et al. Multidimensional Perfectionism Scales (MPS) into a two-dimensional model consisting of Positive Achievement Striving (PAS) and Maladaptive Evaluation Concerns (MEC). PAS is characterized by the setting of high standards for oneself. MEC can be identified by overly critical evaluation of one’s own behavior, an inability to derive satisfaction from achievement, and chronic concerns over other’s criticism and expectations. Researchers studying perfectionism have become increasingly interested in its relationships to academic motivation, effort, achievement and distress. Studies have demonstrated that PAS is associated with intrinsic motivation motivation, high effort and high achievement. (Bieling et al. 2002; Stöeber and Rambow, 2006; Stöeber et al, 2007). Although MEC is also associated with intrinsic motivation, researchers found that it is predominately related to extrinsic motivation and higher stress. Statistics anxiety, or anxiety related to a host of demands typically associated with this type of math class, often predicts poorer performance or greater emotional distress associated with taking a math-related course. Only a few studies have explored the relationship between perfectionism and this specific domain of learning. Past research have shown that the fear of negative evaluation is a common factor to both perfectionism and statistics anxiety (Walsh & Ugumba-Agwunbobi, 2002; Onwuegbuzie & Daley, 1999). Studies have only sampled students who have taken statistics related courses in the past. But for students in other disciplines, anxiety may deter them from ever taking a course that involves statistics. In our study, we hypothesized that in a sample of students who may or may not have taken statistics courses before, PAS will strongly correlate with intrinsic motivation and negatively predict anxiety; MEC will strongly correlate with extrinsic motivation and positively predict anxiety. We planned to use partial correlation to control for the overlap of PAS and MEC. We also hypothesized that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations will have a significant mediating effect on the relationship between dimensions of perfectionism and statistics anxiety. DISCUSSION METHODS Participants and Procedure A total of 272 female students completed an online questionnaire. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 52 years, with a mean age of 20.14 (SD = 4.08) years. The ethnic composition was: 63.1% White/Caucasian, 6.4% African-American, 15.6 % Asian/Pacific I l d 0 Islander, 0.3% 3% Hi Hispanic, i and d 1.7% 1 7% preferred f d nott to t answer. Of the th participants, ti i t 62% h have never ttaken k a statistics t ti ti course, 30 30.4% 4% have h taken an introductory statistics course, and 7.6% have taken advanced statistics courses. Materials Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS; Frost et al., 1990). The FMPS was used to assess the two dimensions of perfectionism: Positive Achievement Striving (PAS) and Maladaptive Evaluative Concerns (MEC). The pure personal standards (PPS) subscale was used (α = 0.78) to measure PAS. The Concern over Mistakes (CM; α = 0.91) and Doubts about Actions (DA; α =0.74) subscales were used to evaluate MEC. Statistics Anxiety Rating Scale (STARS; Cruise et al., 1985). We utilized four of the six STARS subscales: (1) Test and class anxiety, which assesses the anxiety experienced when taking a statistics test or attending a statistics class (α = 0.88); (2) Interpretation anxiety, which measures anxiety when interpreting statistical results (α = 0.89); (3) Ask for help, which evaluates anxiety experienced when an individual intends to ask for help on a statistical question (α = 0.85); and (4) Computation self-concept, self concept, which is designed to assess a person’s self-belief in their ability to cope with the statistics calculations and mathematics (α = 0.87). Work Preference Inventory—Student Version (WPI; Amabile et al., 1994). The WPI was designed to evaluate students’ overall intrinsic and extrinsic motivational attitudes toward their work. The scale consisted of two primary dimensions: (1) intrinsic motivation, which assesses levels of self-determination, competence, task involvement, curiosity, enjoyment, and interest (α = 0.75), and (2) extrinsic motivation, which measures concerns with competition, evaluation, recognition, grades, and constraint by others (α = 0.79). RESULTS We used the Pearson correlation coefficients to examine the relationships between perfectionism dimensions, motivation and statistics anxiety. PAS significantly correlated (p < .05) with both intrinsic (r = .275) and extrinsic motivation (r = .354), but was not significantly correlated with statistics anxiety. MEC was significantly correlated with extrinsic motivation (r = .550) and it was positively correlated with statistics anxiety (r = .418) Intrinsic motivation and statistics anxiety were negatively correlated (r = -.221), but extrinsic motivation and statistics anxiety were positively correlated (r = .276). In a stepwise multiple regression analysis, MEC was the most significant predictor of statistics anxiety (β = .481, p = .000) followed by PAS (β = -.211, p = .001) and intrinsic motivation (β = -.116, p = .041). Extrinsic motivation was not a significant predictor. The correlational analyses showed that PAS and MEC significantly predicted intrinsic and extrinsic motivations and statistics anxiety. Both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations were also correlated with anxiety. To better understand the relationship among the three variables, we conducted multiple mediation analysis to explore the mediating effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the relationship between dimensions of perfectionism and statistics anxiety. Given the overlap between PAS and MEC (r = 0.36), when each perfectionism dimension was considered as the IV in the mediational analysis, the other dimension was covaried out. The analysis showed that PAS had a significant negative direct and total effect on anxiety, while holding MEC as a covariate. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation did not mediate this relationship. MEC had a significant positive direct and total effect on anxiety, while holding PAS as a covariate. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations were both significant mediators in the relationship between MEC and anxiety. Bootstrap results showed that the indirect effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations were equally strong in this relationship (see Table 1) 1). To check for reverse causal effects, we exchanged the independent variable (statistics anxiety) with the dependent variable (dimensions of perfectionism) and tested for effects in the other direction. Anxiety had a significant negative direct and total effect on PAS, although it was smaller than the effect of PAS on anxiety. The indirect effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation was not significant. Anxiety also had a significant positive direct and total effect on MEC, again smaller than the effect of MEC on anxiety. The indirect effects were significant; bootstrap results showed that extrinsic motivation had a stronger indirect effect than intrinsic motivation. Table 1. Sobel and bootstrap analyses (1,000 resamples) of the indirect effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation variables on the relationships between dimensions of perfectionism and statistics anxiety. . IV M1 M2 DV Total Effect (c) PAS Intrinsic Extrinsic Anxiety ‐1.2161*** z‐score of the Direct Effect Indirect Effect (c’) (c‐c’) Contrast* ‐1.2806*** ‐0.0645 N/A 95% CI of the Indirect Effect * Indirect Effect * ‐0.3213 0.2084 MEC Intrinsic Extrinsic Anxiety 0.9788*** 0.8312*** 0.1476* ‐0.0619 0.0306 0.2814 Anxiety Intrinsic Extrinsic PAS ‐0.0521*** ‐0.0430*** ‐0.0091 N/A ‐0.0189 0.0008 Anxiety Intrinsic Extrinsic MEC 0.2309*** 0.1688*** 0.0621* ‐0.0512* 0.0352 0.0930 PAS: Positive Achievement Striving; MEC: Maladaptive Evaluative Concerns. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. *Contrast between the indirect effect of intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation (indirect effect of intrinsic motivation minus indirect effect of extrinsic motivation) *If 0 is not in the 95% confidence interval, then the indirect effect is significant at p < .05 (two tailed). . Positive Achievement Striving: We hypothesized that Positive Achievement Striving as defined by the subscale of Pure Personal Standards would be positively correlated with intrinsic motivation and would negatively predict statistics anxiety. Part of yp was confirmed: we found that PAS is correlated with both intrinsic and our hypothesis extrinsic motivation and PAS negatively predicted statistics anxiety. Although the results differed from our hypothesis, our findings were consistent with a study conducted in 2002 by Mills and Blankstein. They explained that despite setting high standards for themselves, individuals who scored high in subscales of PAS were still primarily motivated by extrinsic compensation and recognition from others. Maladaptive Evaluative Concerns: We hypothesized that MEC would be positively correlated with extrinsic motivation and would positively predict statistics anxiety. The results supported our hypotheses. A positive correlation between MEC, anxiety and extrinsic motivation has also been found in other studies (Mills & Blankstein, 2002; Bieling et al., 2002; Stöeber & Rambow, 2006; Stöeber et al., 2007). A significant correlation was found between the PAS and MEC subscales, which may have influenced their relationships with motivation and anxiety anxiety. Although we used the PPS subscale hoping to control for the overlap, we still found that the two dimensions were not distinct. Multiple Mediation Analysis: The multiple mediation analysis was utilized to explore the mediating effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on the relationship between dimensions of perfectionism and anxiety. When testing for reverse causal effects, we found that dimensions of perfectionism and statistics anxiety have significant direct effects over each other. Although the relationship is stronger from perfectionism to anxiety than the other direction, the cross-sectional design of this study limited our ability to make causal inferences. We found that the mediating effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation were significant only for the MEC and anxiety relationship but not for the PAS and anxiety relationship. This was true for both directions. This finding may offer some support for Stöeber & Otto’s (2006) theory of adaptive and maladaptive dimensions of perfectionism: the strong negative relationship between PAS and statistics anxiety existed regardless of intrinsic or extrinsic motivation, which suggests an adaptive value for the PAS dimension of perfectionism. Future research can clarify the causal relationship and time sequence of the three variables through a longitudinal design. Interaction and moderation analyses may be conducted to examine the variables of age, gender, race, degree of statistics anxiety, and level of statistics competency in the samples. Implications for the Classroom Setting: Previous research (Seipel & Apigian, 2005) linked statistics anxiety to academic performance and had found a positive relationship between PAS and statistics performance but no relationship between MEC and statistics performance. f Although the scope off our research does not cover academic performance, our study may contribute to the overall understanding of the relationship between perfectionism and performance in the classroom setting. Our results suggested that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation contributed to students’ anxiety levels. The result of our study also suggests that dimensions of perfectionism and anxiety may influence each other in a circular model that is partially mediated by motivations. For example, a student who is concerned about making mistakes may have anxiety about statistics; and the anxiety, through extrinsic motivation, then makes the student doubt even more her ability to succeed in the classroom. However, setting high standards without being over-critical of oneself seems to have a suppressing effect on anxiety. This may better explain the relationship between PAS and academic performance. REFERENCES Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. Bieling, P. J., Israeli, A., Smith, J., & Antony, M. M. (2003). Making the grade: The behavioural consequences of perfectionism in the classroom. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(1), 163-178. Brackney, B. E., & Karabenick, S. A. (1995). Psychopathology and academic performance: The role of motivation and learning strategies. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(4), 456-465. DiBartolo, P. M., Li, C. Y., & Frost, R. O. (2007). How do the dimensions of perfectionism relate to mental health? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 32(3), 401-417. Dunkley, D. M., Blankstein, K. R., Masheb, R. M., & Grilo, C. M. (2006). Personal standards and evaluative concerns dimensions of “clinical” perfectionism: A reply to shafran et al. (2002, 2003) and hewitt et al. (2003). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 63-84. Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468. Frost, R. O., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Neubauer, A. L. (1993). A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 14, 119–126. Hanna, D., Shevlin, M., & Dempster, M. (2008). The structure of the statistics anxiety rating scale: A confirmatory factor analysis using UK psychology students. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(1), 68-74. Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2002). Perfectionism and stress processes. In: G. L. Flett & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 255–284). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. MacKinnon, D. P. (2004). Mediating variable. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Retrieved March 23, 2009, from http://www.sciencedirect.com Mills, J. S., & Blankstein, K. R. (2000). Perfectionism, intrinsic vs extrinsic motivation, and motivated strategies for learning: A multidimensional analysis of university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(6), 1191-1204. Miquelon, P., Vallerand, R. J., Grouzet, F. M. E., & Cardinal, G. (2005). Perfectionism, academic motivation, and psychological adjustment: An integrative model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(7), 913-924. Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Daley, C. E. (1999). Perfectionism and statistics anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 26(6), 1089-1102. Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In A. F. Hayes, M. D. Slater, & L. B. Snyder (Eds.), The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research (pp. 13-54). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Rodarte-Luna, B., & Sherry, A. (2008). Sex differences in the relation between statistics anxiety and cognitive/learning strategies. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33(2), 327-344. Seipel, S. J., & Apigian, C. H. (2005). Perfectionism in students: Implications in the instruction of statistics. Journal of Statistics Education, 13. Retrieved February 10, 2009, from http://wwamstat.org/publications/jse/v13n2/seipel.html Stöeber, J., & Eismann, U. (2007). Perfectionism in young musicians: Relations with motivation, effort, achievement, and distress. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(8), 2182-2192. Stöeber, J., & Rambow, A. (2007). Perfectionism in adolescent school students: Relations with motivation, achievement, and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(7), 1379-1389. Stöeber, J., Stoll, O., Pescheck, E., & Otto, K. (2008). Perfectionism and achievement goals in athletes: Relations with approach and avoidance orientations in mastery and performance goals. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 9(2), 102-121. Walsh, J. J., & Ugumba-Agwunobi, G. (2002). Individual differences in statistics anxiety: The roles of perfectionism, procrastination and trait anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(2), 239-251.