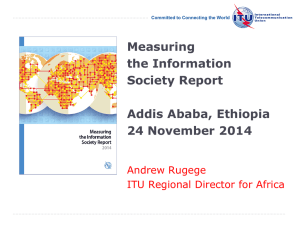

Measuring the Information Society Report 2015

advertisement