Agricultural Economics presented on for the (Name of student)

advertisement

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF

for the

SHENG HUI LIAO

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

(Degree)

(Name of student)

in

Agricultural Economics

presented on

(Major)

Title:

May 16, 1973

(Date)

AN ANALYSIS OF THE DIFFERENCES IN THE MARGINAL

PROPENSITY TO CONSUME OF FARM. RURAL NONFARM

AND URBAN FAMILIES IN THE

Abstract approved:

ITED STATES. 1961

Redacted for Privacy

John A. Edwards

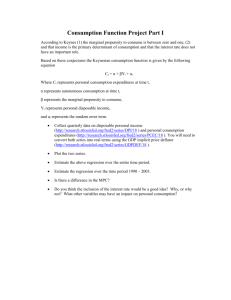

The study was conducted to obtain information concerning the

factors affecting the differences in the marginal propensities to consume of farm and nonfarm families observed by Friedman and Lee

and Phillips. As a first step a theoretical framework was developed

which indicated the factors affecting the marginal propensity to con-

sume. From this framework, two hypotheses were formulated for

explaining observed differences in the marginal propensities to

consume between farm and nonfarm families: (1) Farm and nonfarm consuming units with homogeneous socioeconomic character-

istics have the same marginal propensity to consume, and (2) distribution of consuming units by socioeconomic characteristics in the

farm sample is different from that of consuming units in the nonfarm sample.

Next a model and statistical procedure for testing the hypotheses were developed. The dummy variables technique was used as

a means of quantifying the socioeconomic variables and thus of

measuring their effect on the marginal propensity to consume.

Finally, the model was fitted to data obtained from the Bureau of

Labor Statistics and the U. S. Department of Agriculture--Survey

of Consumer Expenditure, 1960-61--using least squares procedures.

The empirical results indicated that there were no significant

differences in the marginal propensities to consume between farm

and nonfarm families with homogenous socioeconomic character-

istics for the majority of the 17 tested groups, However, those

groups in the Northcentral and Western regions were the exception.

In these two regions, farm families had a lower marginal propensity

to consume than did nonfarm families.

This could be due to

differences in the prices paid by farm and nonfarm families in these

two regions.

The empirical results also indicated that there were significant

differences in the distribution of families by socioeconomic char-

acteristics between the farm and nonfarm samples. Thus, the

observed differences in the marginal propensities to consume between

farm and nonfarm families could be due to the differences in the

distributions of family types in the two samples.

An Analysis of Differences in the Marginal Propensity

to Consume of Farm, Rural Nonfarm, and Urban

Families in the United States, 1961

by

Sheng Hui Liao

A THESIS

submitted to

Oregon State University

in partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the

degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

June 1974

APPROVED:

Redacted for Privacy

Professor of Agricultural Economics

Iin charge of major

Redacted for Privacy

Head of Department of Agricultural Economics

Redacted for Privacy

Dean of"Graduate School

Date thesis is presented

May 16, 1973

Typed by Velda D. Mullins for

Sheng Hui Liao

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author owes a special debt of gratitude to

Dr. John A. Edwards, major professor, for his constructive suggestions at all stages of this study and

guidance throughout the authorTs graduate program at

Oregon State University.

He is grateful to Drs. Timothy M. Hammonds, Joe

B. Stevens, Bruce R. Rettig, Richard S. Johnston, William

G. Brown, and Mr. Ancel D. Haroldsen for their helpful

comments and assistance on the dissertation.

He also wishes to express his sincere appreciation

to the Department of Agricultural Economics, Oregon State

University, for providing financial assistance during the

entire period of his graduate study and also to the Computer

Center, Oregon State University, which provided a grant in

support of this study.

The authors greatest debt is to his wife for her

patience and her sacrifices throughout his graduate work.

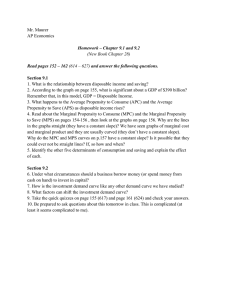

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Chapter

I

II

INTRODUCTION

1

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

6

Consumer Choice and the Marginal Propensity

to Consume

The Formulation of Hypotheses

III

IV

THE MODEL AND STATISTICAL PROCEDURE

12

The Model

12

The Statistical Procedure

13

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

The Data

The Definitions

The Marginal Propensity to Consume Out of

Disposable Money Income

The Marginal Propensity to Consume Out of

Total Disposable Income

V

6

10

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Validity of the Hypotheses

Comparison with Previous Studies

Methodological Conclusions

Policy Implications

Implications for Future Research

21

21

22

26

56

65

65

68

71

73

75

BIBLIOGRAPHY

76

APPENDIX A The Equality of Regression Coefficients of

the Dummy Variables Regression Model and

the Ordinary Regression Model

79

APPENDIX B The Distribution of Families in the Sample

by Socioeconomic Characteristics

85

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table

1

2

Regression coefficients and related statistics

of urbanization equation in the U.S., 1961

Differences in the marginal propensities to consume

and their t-values for farms, rural, nonfarm, and

urban families in the U. S.,

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

28

1961

Regression coefficients and related statistics of

regionality equation in the U. S., 1961

30

31

Differences in the marginal propensities to consume

and their t-values for four regions in the U. S.,

1961

32

Regression coefficients and related statistics of

education equation in the U.S., 1961

33

Differences in marginal propensities to consume

and their t-values for four educational levels of

family head in the U.S., 1961

34

Regression coefficients and related statistics of

ages equation in the U.S., 1961

35

Differences in the marginal propensities to consume

and their t-values for six age groups in the U. S.,

1961

36

Regression coefficients and related statistics of

family size equation in the U.S., 1961

38

Differences in the marginal propensities to consume

for seven family size groups in the U.S., 1961

40

Regression coefficients and related statistics of

occupation equation in the U.S., 1961

41

Table

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Page

Differences in the marginal propensities to

consume for seven occupational groups in the

U.S., 1961

44

Multiple regression coefficients and related

statistics in farm and nonfarm families, U. S.,

1961

47

Socioeconomic characteristics of the family in

each group

50

Distribution of families in the farm and the nonfarm samples by characteristics of the family

51

Consumption functions and related statistics for

selected homogeneous groups of farm and nonfarm

families in the U.S., 1961

53

Regression coefficients and related statistics of

urbanization equation and three urbanization

families in the U.S., 1961

58

Differences in the marginal propensities to

consume out of total disposable income and their

t-values for farm, rural nonfarm and urban

families in the U.S., 1961

59

Multiple regression coefficients and related

statistics to farm and nonfarm families, U.S., 1961

60

Consumption functions and related statistics for

selected homogeneous groups of farm and nonfarm

families in the U.S., 1961

62

Distribution of families in the farm and the nonfarm samples based on socioeconomic characteristics

67

Comparison of current study and Friedman's study:

the marginal propensities to consume of farm, rural

nonfarm, and urban families in the U. S.

69

AN ANALYSIS OF DIFFERENCES IN THE MARGINAL

PROPENSITY TO CONSUME OF FARM, RURAL

NONFARM, AND URBAN FAMILIES IN THE

UNITED STATES, 1961

I INTRODUCTION

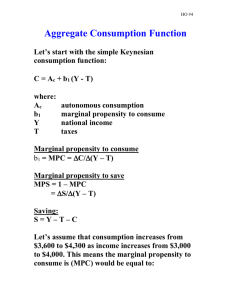

The marginal propensity to consume is defined as the change

in consumption expenditure in response to a change in income. In

simple macro-models the marginal propensity to consume is as-

sumed to be essentially the same for all consumers. However, empirical studies by Friedman [ii] and Lee and Phillips {19] have concluded that there are significant differences between farm and

non.-

farm families, as well as other socioeconomic groups, in their

consumption response to changes in income.

Friedman estimated the marginal propensity to consume at

0. 50 and 0. 73 for farm and nonfarm families, respectively, using

1935-36 data. Based on 1941 data, the marginal propensity to con-

sume of farm families was about 0. 48 and that of urban families was

0. 79. According to Friedman, the observed differences in behavior

are consistent with his permanent income hypothesis.

The permanent income hypothesis can be stated by three

equations for the individual consuming unit:

2

= K (i,

(1. 1) C

W,

u) Y

(1.2)Y =Yp+Yt

(1.3)C =C+C

Equation (1. 1) asserts that the ratio (K) between permanent

consumption

(Ce) and permanent income

(Yr)

is independent of the

size of permanent income but does depend on other variables:

(1)

the rate of interest (i), (2) the ratio of nonhuman wealth to income

(w), and (3) other factors affecting the consuming unit's tastes and

preferences (u).

Equations (1.2) and (1. 3) are definitional. A consuming unit's

current income (y) and consumption (c) have permanent and transi.tory components. The permanent income of a consuming unit is

defined as the product of an interest rate (i) and the stock of wealth

(w); and the stock of wealth is interpreted as the present value of

anticipated future receipts from both human and nonhuman assets

discounted back to the present at a subjective rate of interest. The

permanent income is thus a theoretical construct. The amount by

which current income differs from permanent income is called

transitory income which reflects the influence of factors regarded

as chance or random by the consumer unit, as well as errors of

mea surement.

The permanent income hypothesis in the above form is incap-.

able of being tested empirically because neither permanent income

3

nor permanent consumption can be observed directly for an individual consuming unit. To make the hypothesis testable, Friedman

assumes that

(1.4)

=0

p

where p denotes the correlation coefficient between the variables

designated by the subscripts.

In addition to equation (1.4), it is also assumed that the mean

transitory component of both consumption and income are zero, or

(1.5)

0

With these assumptions, Friedman derived the following

equation for interpretation in terms of the permanent income hypothes is:

(1.6)

b

=K

(YY)2

(Y-Y)2

=KP y

where b is the marginal propensity to consume out of current income, P,. is the fraction of the total variance of income in the group

contributed by the permanent income, and K is as defined in equation (1. 1).

In his budget studies, Friedman, observing that farm

families have a lower marginal propensity to consume and a lower

value of

than do nonfarm families, concluded that the entre-

prenurial nature of farmer's income has greater uncertainty than

do other types of income. Furthermore, farm families were

expected to have a lower K because of their lower average income.

Thus, the differences in the consumption responses to changes in

income between farm and nonfarm families could be explained by

the permanent income hypothesis.

In 1 971, Lee and Phillips conducted a study to test the validity

of Friedman's permanent income hypothesis in explaining the differences in consumption behavior between farm and nonfarm fam-

ilies. Their findings indicated that the level and the stability of

income were not important contributing factors to observed differences in behavior. In their study, it was assumed that the perman-

ent income hypothesis is applicable for the different categories of

consumption.

The model used by Lee and Phillips was estimated by two

stage least squares. The model employed the assumption that the intercept and other regression coefficients are the same for farm and

nonfarm samples. This assumption may result in biased estimates

of the slopes, if in fact there are different intercepts for both groups.

In addition, group mean data were used in their analysis. Freund

[ii] indicated the the use of group means for performing regression

analysis is inferior to the use of all observations because of low

efficiency and precision..

In summary, the results of previous studies, while of interest,

are unsatisfactory because of conflicting findings in establishing the

5

permanent income hypothesis as an explanation of the differences

in consumption patterns between farm and nonfarm families.

Furthermore, neither of these studies has analyzed the factors

affecting K--the ratio of permanent consumption to permanent income. This is an essential aspect of the permanent income hypoth-

esis for understanding the consumption behavior of consumer units.

Thus, observed differences in the marginal propensities to consume

between farm and nonfarm groups still require further investigation.

Hence, the main objective of this study is to determine the

factors affecting the differences in the marginal propensities to

consume of farm and nonfarm families. To achieve this objective,

individual observation data from the Survey of Consumer Expenditure

were chosen for the study because it contains detailed information of

socioeconomic characteristics for the sample households.

The plan of this study is as follows: Chapter II deals with a

theoretical framework. Chapter III is devoted to a discussion of

the model and statistical procedure. Chapter IV is concerned with

the statistical results. Finally, Chapter V gives conclusions and

the implications of the study.

II THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This chapter deals with the theoretical basis of consumption

analysis. There are two sections. In the first section, factors

affecting the marginal propensity to consume are identified in the

context of the theory of consumer choice under constraint. The

second section is devoted to formulating hypotheses.

Consumer Choice and the Marginal

Propensity to Consume

The assumptions of consumer choice are (1) a consumer has a

given utility function which specifies his preferences for various

goods and services, (2) a consumer is subject to a budget restraint

in his choices of goods and services, and (3) the consumer attempts

to allocate his limited budget among available goods and services

so as to maximize his utility or satisfaction.

According to these assumptions, consumers maximize a

utility function of the form

U = Y (X1, X2,

(2.1)

.

.

Xni Xn)

subject to the budget constraint.

Y=

(2.2)

where X1, X2,

.

.

P.X.

11

X_q represent the consumption levels of the

n-i commodities, Xn represents the level of money balances,

7

P. are their prices, and Y is income.

However, this study deals with consumer choice between the

aggregate of all commodities and money balances. The aggregate

of all commodities can be denoted as q1

=

(X1, X2,

.

.

., Xi);

money balances are q2 = X. Thus, the consumer's choices are

limited to q1 and q2. The consumer's utility function can be ex-

pressed as:

(2. 3)

U=

q1, q2)

The consumer's budget constraint can be written as follows:

f(2.4)

Where P

Y = Pq1 + q2

(P1, P2.

.

.

., P1) represents a price index and the

price of q2, money balances, is always equal to one.

To maximize the utility function subject to the budget constraint the consumer should find a combination of commodities and

money balances that satisfies equation (2. 4) and also maximizes

equation (2. 3). One can construct the function:

(2. 5)

L=

(q1,

q2) + X (Y - Pq1 - q2)

where X is a Lagrangean multiplier. Maximizing L requires that

the first and the second order conditions be satisfied.

The first order conditions are that both partial derivatives

equal zero:

(2.6)

ci

(2.7)

= XP

X

2

0

=0

Thus, one obtains the first order condition from equations

(2. 6)and

(2.7)

as

ci

(2.8)

=p

This is a necessary condition for a maximum, but it does not

ensure that a maximum is actually reached. The second order condition must also be satisfied.

The second order condition requires:

-

(2. 9)

2P21 +P2

dq12

22

<0.

Taking the total derivative of the first order condition, one

would obtain an equation as follows:

dq1 +

-

(2. 10)

-

Pct

dq2 = 0.

Equation (2. 10) can also be written as:

(2. 11)

dq

2l

11

(

)

dq1

Taking the total derivative of the budget constraint, the

equation obtained is:

(2. 12)

dY = Pdq1 + dq2.

1"

Substituting equation (2. 12) into equation (2. 11), gives:

dq1

(2. 13)

22

12

dY

- 2P21

Thus,

dq1P

(2.14)

dY

PI)22

12

=

2zi +

i1

dq1P

where

dY

is the marginal propensity to consume which is de-

fined as the ratio of the change in consumption expenditure to the

change in income. Note that the right-hand side of equation (2. 14)

consists of the price index and elements from the utility function of

the consumer. Therefore, factors affecting the marginal propensity

to consume can be written in the functional relationship as

dq1P

(2. 15)

dY

=

lIP,

4)

°'i' q2)]

Thus, the marginal propensities to consume of two consumers

will differ if (1) their utility functions are different; or (2) the

prices which they pay are different; or (3) both.

Specifically, if two consumers have linear consumption func-

tion such as:

(2. 16)

C.I = a. + 3. Y.

I

1

1

Where C. is the expenditure for current consumption of the ith

consumer, Y. is his income, a. is an intercept, and 1 is his

10

marginal propensity to consume,

13.

will differ between consumers

only if one of the above conditions is true.

The Formulation of Hypotheses

The conclusion reached in the preceding discussion is that the

marginal propensity to consume is determined by the consuming

unit's utility function and the price level. The prices paid by con-

suming units are usually not available in cross sectional data; the

failure to include price is, essentially, equivalent to assurrLing that

the price level is the same for all consuming units in the sample.

Furthermore, it is difficult to measure the consuming unit's utility

function empirically.

However, socioeconomic characteristics of consuming units

can be observed directly. Changes in socioeconomic characteris-

tics of consuming units generally contribute to changes in their

tastes and preferences. It is associated with the utility function.

Thus, the marginal propensity to consume will be a function of

socioeconomic conditions of the consuming units. The marginal

propensity to consume of two consuming units will differ if their

characteristics are different. This discussion suggests one testable

hypothesis concerning the marginal propensity to consume of farm

and nonfarm consuming units:

11

Hypothesis #1. Farm and nonfarm consuming units with honogeneous socioeconomic characteristics have the same

propensity to consume.

If this hypothesis is accepted, then observed differences in

the marginal propensities to consume for farm and nonfarm consuming units by the previous studies could be due to differences

in the distribution of consuming units by socioeconomic character-

istics in the two samples. This argument suggests one more testable hypothesis:

Hypothesis #2: Distribution of consuming units by socioeconomic

characteristics in the farm sample is different

from that of consuming units in the nonfarm sample.

The acceptance of these hypotheses will provide an explanation

for observed differences in the consumption behavior between farm

and nonfarm consuming units. It also provides evidence for the

prediction from the theory of consumer choice that the marginal

propensity to consume is determined by the utility function and the

price level.

12

III THE MODEL AND STATISTICAL PROCEDURE

In the preceding chapter a theoretical framework was presented. The present chapter is an attempt to derive the model and

the statistical procedure for estimating the model and testing the

hypotheses. These are presented below.

mL.

In Chapter II, it was argued that the marginal propensity to

consume is a function of utility function which is, in turn, assumed

to be a function of the socioeconomic characteristics of the consuming unit. This can be expressed as below:

(3. 1)

p

= f (Xi,

.

.

.

,

X

n

where p is the marginal propensity to consume and X1, X2,

.

Xncorrespond to the socioeconomic characteristics of the consuming unit. The functional relationship of (3. 1) may be explicitly

written as;

(3. 2)

where p0, p1,

p0 + p1X1 + p2X2 +

p

.

.

.,

p

+

X

are parameters. Substituting equation

(3. 2) into a consumption function, i. e., C = a + pY, it becomes

(3.3)

XY

X Y+p22

X Y+. . . +p nfl

C = a+p 0Y+ 11

where C is expenditure for current consumption and Y is disposable

13

income.

Equation (3. 3) takes factors affecting the marginal

propensity to consume into consideration. However, the estimate

of the intercept (a) is also affected by characteristics of the consuming units because a is a function of p

i. e., a = C - pY.

Thus, the consumption function can be rewritten as:

(3.4)

C = A0 +A11

X +.

+ 13 Y +

0

1

X Y.

11

.

.

. +A nn

X

.

nn

+ p x Y

Equation (3.4) is an econometric model used in this study.

The Statistical Procedure

The first problem the researcher encounters in estimating

equation (3. 4) is the selection of the independent variables (X1, X2,

Xn) to be included in the equation. The variables selected in

this study include (1) size of the consuming unit, (2) education

level, (3) occupation, (4) age, (5) regionality, and (6) urbanization.

The selection is based on a priori reasoning and available data,

since it is neither practical nor possible to include in the model all

of the socioeconomic characteristics which may influence the taste

and preferences of the consuming unit.

The reasons for not using permanent income are (1) t1is

study is not testing the permanent income hypothesis, and (2) it is

very difficult to quantify and measure the term empirically.

14

Since the variables selected are classification variables

rather than continuous variables, it is difficult to quantify them.

To overcome this obstacle, dummy variables are used to measure

them. Each variable takes a value of one or zero, depending upon

whether or not the observation is in the particular class represented

by that dummy variable. In order to avoid the problem of over-

identification which is created by perfect correlation involved in a

set of dummy variables which are mutually exclusive, a constraint

must be placed on the system. This constraint is to drop one of the

dummy variables from each mutually exclusive system. The re-

maining variables would no longer be perfectly correlated and the

solution for the parameters would be obtainable.

The ordinary least squares method is then employed to estimate the regression coefficients of the consumption function. But

the selected variables have about 32 classes with more than ten

thousand observations which is over the capacity of available com-

puting facilities. So the first step is to attempt to reduce the number

of variables involved. The method adopted is to run regression

analyses for each socioeconomic variable separately.

The regression equation for each socioeconomic variable is

presented below:

15

Urbanization equation:

(3.5)

2

C = A uo

+

i=1

2

Aui.U.+ p uo Y+

1

i=1

piii.U.Y+E U

Regionality Equation:

3

(3.6)

C = A ro

+

i=1

3

Ari.R.+proY+

1

i=1

pri.R.Y+E r

1

Education equation:

(3. 7')

3

C = A eo

3

Aei.E. + p eo Y + E p ei.E.Y + E

+

i-i

1

1

1=1

e

Age equation:

5

(3.8)

C = A ao

5

+

IZ1

Aei.A. + p ao Y +

1

i=1

pai.A.Y + E a

1

Size equation:

6

(3.9)

C = A SO

6

+

i=1

ASi.S. + p so Y + E pSI.S.Y + E S

1

1

i=1

Occupation equation:

6

(3.10)

6

C=A00+A.O.+p 00Y+p.O.Y+E

01

1

i=l

where

01

1

0

C = expenditure for current consumption

Y = disposable income

u1 = 1, if the consuming unit lies in rural nonfarm

sample; = 0, otherwise.

16

u2

R1

=

1,

if the consuming unit lies in urban sample;

=

0,

otherwise.

=

1,

if the consuming unit lies in the Northcentral

region;

R2

= 1,

=

0,

=

0, otherwise.

if the consuming unit lies in Southern region;

otherwise.

R3 = 1, if the consuming unit lies in Western region;

= 0, otherwise.

1,

if 8 years or less of education;

=

0, otherwise.

0, otherwise.

E2

=

1,

if 9-12 years of education;

E3

=

1,

if 13-16 years of education;

A1

=

1,

if <24 years old;

A2

=

1,

if 25-34 years old;

A3

= 1,

if 35-44 years old;

A4

=

1,

if 45-54 years old;

=

0, otherwise.

A5

= 1,

if 55-64 years old;

=

0, otherwise.

S1

=

=

=

0,

=

=

0, otherwise.

otherwise.

0, otherwise.

0, otherwise.

1,

of 2.0-2.9 persons in the consuming unit;

0,

otherwise.

S2 = 1, if 3.0-3.9 persons in the consuming unit;

= 0, otherwise.

S3 = 1, if 4. 0-4. 9 persons in the consuming unit;

= 0, otherwise.

S4 = 1, if 5. 0-5.9 persons in the consuming unit;

17

= 0, otherwise.

S5 = 1, if 6. 0-6. 9 persons in the consuming unit;

0, otherwise.

= 1, if 7. 0-7. 9 persons in the consuming unit;

= 0, otherwise.

01 = 1, if self-employed;

=1

0, otherwise.

if professional and managers; = 0, otherwise.

03 = 1, if clerical and sales;

0,

otherwise.

04 = 1, if skilled workers; = 0, otherwise.

05 = 1, if semi-skilled workers; = 0, otherwise.

= 1,

E

if unskilled workers; = 0, otherwise.

= the error term.

Once the regression coefficients for the above equations are

obtained, one can then derive the marginal propensity to consume

(MPG) for each class of the selected variables. For instance, the

estimated urbanization equation is as follows:

A

(3.11)

G =A uo

A

A

+A.0

+Au2U

ui

2 +puoY+.UY+

ui

1

1

A

uZUY

2

Then, the equations for each urbanization class can be derived from

equation (3. 11) as follows:

Farm consuming unit:

(3.12)

A

G =Auo

A

+13

uo

Urban consuming unit:

EI]

(3.13)

A

C =(A uo +AUi)+(1A UO +p Ui.)Y

A

Rural nonfarm consuming unit

(3.14)

C =(A uo +Au2)+(p uo

A

+pu2)Y

A

Thus, the marginal propensity to consume obtained from

equations (3. 12), (3. 13), and (3. 14) for farm, urban, and rural

A

nonfarm consuming units are 3uo ,

p

uo + p ui., and 13 uo

A

+ P

uZ

respectively. An interesting feature about the regression coefficients in equations (3. 12), (3. 13) and (3. 14) is that they are ex-

actly the same as those that would be obtained from three separate

regressions of C on Y, one estimated from farm observations, and

the other from urban and rural nonfarm observations.

A signifi-

cant advantage of using the dummy variable regression technique

over the separate independent regression technique is that the

number of degrees of freedom is considerably greater permitting

more powerful tests of significance.

To determine if the marginal propensity to consume of one

urbanization group (MPC.) is different from that of the other group

(MPG.), one must determine whether or not there is a significant

difference between MPG. and MPG.. The t-test is used;

1

J

For proof, see AppendixA.

19

MPG. - MPG.

1

(3.15)

S2

i

-MPG)

If the value of this statistic is significantly different from

zero, the hypothesis that MPG. = MPG. is to be rejected. The

results of the t-tests for each class of the variables selected provide a basis upon which to group several classes together, thereby

reducing the number of variables involved in the model.

The next step is to introduce those explanatory variables

identified from the results obtained in the above process into the

dummy variable regression model in equation (3. 4) for farm and

nonfarm consuming units. The MPG's for farm and nonfarm con-

suming units with respect to a particular set of homogenous char-

acteristics can be obtained from the estimated regression equation.

These MPG's are then subjected to the t-test. This is a test of

the hypothesis that there is no significant difference in the marginal

propensity to consume for farm and nonfarm consuming units when

they have homogeneous socioeconomic characte ristics.

To test the hypothesis that there is a significant difference in

the distribution of consuming units by socioeconomic characteristics

for farm and nonfarm samples, the consuming units were first

grouped according to socioeconomic characteristics. This tabular

analysis provides a measure of the distribution of consuming units

20

in the two samples. The percentage of consuming units with

certain types of socioeconomic characteristics studied is then

calculated for each sample. Finally, the t-test is used to deter-

mine statistical significance of difference in this percentage between

farm and nonfarm samples.

21

IV EMPIRICAL RESULTS

This chapter begins by discussing the source of the data and

the terms used in this study, thus providing the background for understanding the subsequent discussion of analyses. It is then devoted

to discussing statistical results: (1) the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable money income, and (2) the marginal propensity to consume out of total disposable income.

ffil-..

T\-4-.

The data employed in the following analysis was obtained from

the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Department of Agriculture--Survey of Consumers Expenditure Conducted in 1960-61. A

three-stage sample design was used to select a sample representing

families and single consumers in the population.

The data were

collected by personal interviews. The survey contained 13, 728

observations.

For this study, only selected observations within the total

sample were considered. The selection was based on the following

criteria:

3' For detail on sampling method, see [26, p. 11-16].

22

(1) Income is in the range of $0 to $15, 000.

Those observations not in this range were excluded on the grounds

that they represented extreme cases.

(2) Only households of two or more persons were considered.

Those households with average annual family size of less than two

persons are comprised of bachelors, unmarried women, the

divorced, widows and widowers. This is a very heterogeneous

group, and thus they were eliminated from the analysis.

(3) Those observations where family size, education of head,

age of head, and occupation of head were not reported were excluded.

This was necessary because these observations could not be analyzed due to lack of information concerning relevant variables.

Based on the above criteria, 10, 218 families were selected

for this study. In the empirical analysis of this study, the family is

considered to be the consuming unit. However, as discussed in the

previous chapters, a consuming unit may be either an individual

consumer or a family.

The Definitions

Family

The family is defined as two or more persons dependent on a

common, or pooled, income for their major items of expenditure,

23

and usually living in the same household.

Family Size

It is the number of equivalent full-year members, based on

the total number of weeks during which both full and part-year mem-

bers belonged to the family in the survey year. Fifty-two weeks of

family membership are considered equivalent to one person, et

cetera.

Family Head

In husband-wife families, the husband is always considered

the head. In other types of families, the person recognized as the

head by other family members is so designated.

Education of Family Head

The number of years of study completed by the family head by

the end of the survey year in schools which advance a person to an

elementary or high school diploma, or to college, university or professional school degree.

Age of Family Head

It is that recorded as the age in years of the family head at

the end of the survey year.

24

Occupation of Family Head

It is based on the family head's major occupation, i.e., the

occupation at which the family head was employed for the greatest

number of weeks in the survey year.

Urban Families

Families that reside in incorporated places of 2, 500 population

or more and in the densely settled areas immediately adjacent to

cities of 50, 000 population or more.

Rural Nonfarm Families

Families that reside outside of urban areas, but not on farms.

Rural Farm Families

Families that reside outside of urban areas, and on a farm,

defined as in the 1960 Census as a place of 10 acres or more from

which the sale of crops, livestock products, et cetera, amounted to

$50 or more; or a place of less than 10 acres with sales of $250 or

more.

25

Northeast Region

It includes the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont,

Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey.

Nortbcentral Region

This region consists of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan,

Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South

Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas.

Southern Region

It includes Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North Caro-

lina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee,

Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas.

Western Region

This includes Montana, Idaho, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah,

Washington, Oregon, California, Wyoming, Nevada, and Arizona.

Money Expenditure for Current Consumption

These expenditures consist of cash outlays for goods and

services for family living during the survey year.

Total Expenditures for Current Consumption

It includes cash and noncash outlay for goods and service for

family living.

Disposable Money Income

It has been measured by total money income after deduction

of personal taxes.

Total Disposable Income

It is total money and nonmoney income after taxes.

The Marginal Propensity to Consume Out of

Disposable Money Income

The marginal propensity to consume out of disposable money

income is defined as the ratio of the change in money expenditures

for current consumption to the change in disposable money income.

This can be obtained from the slope of the linear regression of

money expenditure (C1) on disposable money income (Y1). The

statistical procedure used in this regression analysis has been discussed in Chapter III. The results of the empirical estimation of

the coefficients for each socioeconomic variable are presented

below.

27

The regression coefficients of the urbanization equation in

Table 1 are computed by least square multiple

regression.'

The

figures in the parentheses below the coefficients are the t-values.

All coefficients in equation (4. 1) are significantly different from

zero at the one percent level in a t-test. The estimate of the coefficient of multiple determination (R

2.is 0. 65.

)

This indicates that

about 65 percent of the variation in money expenditure is explained

by the variables used in. the analysis.

The equations for rural nonfarm families, urban families, and

rural farm families are derived from equation (4. 1). All coefficients

in equations (4. 2), (4. 3) and (4. 4) are significant at the one percent

level. -" Equation (4. 2) indicates that the marginal propensity to

1etroscedasLicity in the. regression model was not examined in the study because it would be too costly to calculate

residuals for 10, 218 observations in each regression equation.

No high degree of multicollinearity in the regression equations is

present by observing the correlation coefficient matrices. In

general, size of sample tends to infinity the problem of high degree

of multicollinearity decreases. The size of sample in this study

being 10, 218 is so large. Thus, the problem of high degree of

multicollinearity is not likely to occur.

The following was used to calculate a t-value for derived

equations:

a. + a.

I:

s.e. (a. +a.

1

3

1/2

where s. e. (a. + a)

[Var a. + Var a. + 2 Coy a.a.]

13

3

For a further discussion, see Kmenta [16] and Gujarati [13].

1

.1

1

Table 1. Regression coefficients and related statistics of urbnization equation in the U. S., 1961.

Constant term

Equation

U

1

U

2

Y

1

UY

1 1

UY

2 1

Urbanization:

1655.90

(22.32)**

(4.1) C1

-644.73

(-5.90)**

-435.04

(_4.94)**

0.4649

(33.21)**

Rural nonf arm families:

(4.2) C1

1011.17

(5.99)**

0.7255

(52.96)**

1220.86

0.7393

(108. 72)**

Urban families

(4.3) C

(7.84)**

Rural farm families:

1655.90

(4.4) C1

(22. 32)**

where

money expenditure for current consumption

C1

= disposable money income

U1

U2 =

1,

if the rural nonfarm families; = 0, otherwise

1,

if the urban families; = 0, otherwise

** Significant at the 1% level.

0. 4649

(33. 21)**

0.2606

(13.33)**

0.2744

(17.64)**

0.65

29

to consume out of disposable money income is 0. 4649 for farm

families. Thus, an increase of disposal money income by one

dollar would bring an increase in money expenditures of about 46

cents in the farm families. Similarly, equations (4. 3) and (4. 4)

indicate that the marginal propensities to consume are 0. 7255 and

0. 7393 for rural nonfarm and urban families, respectively.

The results of testing the differences in the marginal propen-

sities to consume for farm, rural nonfarm, and urban families are

given in Table 2. The test provides evidence that the marginal pro-

pensity to consume for farm families is significantly different from

that of rural nonfarm families and urban families. However, there

is no significant difference in the marginal propensity to consume

between rural nonfarm and urban families. Thus, these findings

support Friedman's conclusion that farm and nonfarm families have

different marginal propensities to consume.

The regression coefficients presented in equations (4. 6), (4. 7),

(4. 8), and (4. 9) in Table 3 are significant at the one percent level.

The marginal propensities to consume are about 0. 7477 and 0. 7305

for the Northeast region and the Southern region, respectively,

while that of the Northcentral region and the Western region are

about 0. 6714 and 0. 6824, respectively. The results of testing the

differences in the marginal propensities to consume show that the

marginal propensity to consume of the Northeast region is not

30

Table 2. Differences in the marginal propensities to consume and

their t-values for farm, rural, nonfarm, and urban

families in the U.S., 1961.

Rural nonfarm

Rural nonfarm

Urban

Farm

0

(0)

Urban

Farm

-0. 0138

0

(-0.91)

(0)

0. 2606

(13. 33)**

0. 2744

(17. 64)**

0

(0)

** Significant at the 1% level.

significantly different from that of the Southern region. Similarly,

there are no significant differences in the marginal propensities to

consume between the Northcentral region and the Western region

(Table 4).

The above evidence reveals the existence of regional variations

in the marginal propensity to consume. These variations may re-

flect regional differences in (1) cost of living, (2) customs, and (3)

tastes conditioned to climate.

Educational attainment of the family head presented as a

variable in the regression analysis appears to be related to the

family's consumption patterns (Table 5). The marginal propensity

to consume is lower for families whose head had been in college or

in graduate school. Table 6 shows that the marginal propensity to

Table 3. Regression coefficients and related statistics of regionality equation in the U. S., 1961.

Equation

Constant term

R1

R2

R3

1247.72

(14.90)**

18.59

-299.06

(_2.93)**

435. 12

(0.17)

Y1

R1Y1

R2Y1

R3Y1

Regionality equation:

(4.5) C1

0.7477

(3.30)** (62.08)**

-0. 0763

-0. 0172

-0. 0653

(-4.81)**

(-1.09)

(_3.55)**

0.63

Northc entral region:

(4.6) C1

1266.30

(18.66)**

0.6714

(25.63)**

948.66

(5.3S)**

0.7305

(27.99)**

1682.84

(16.49)**

(24. 55)**

1247.72

(14.90)**

0.7477

(62.08)**

Southern region:

(4.7) C1

Western region:

(4.8) C1

0.6824

Northeast region:

(4.9) C1

where

=

Y1

money expenditure for current consumption

disposable money income

=

R2

1,

if Northcentral region;

1,

if Southern region;

0, otherwise

0, otherwise

R3 = 1, if Western region; = 0, otherwise

**

Significant

at the 5% level.

I-'

32

Table 4. Differences in the marginal propensities to consume and their t-values for four regions

intheU.S., 1961.

Northc entral

Northcentral

Southern

Western

Northeast

0

(0)

Southern

Western

-0. OSO 1

0

(4.28)**

(0)

-0.0110

(0.63)

Northeast

0.0481

(2.86)**

-0. 0763

-0. 0172

(-4.81)**

(-1.09)

0

(0)

-0. 0653

(_3.55)**

0

(0)

** Significant at the

consume for eight years or less of education of the family head is

not different from that of 9 or 12 years education of the family head.

The effect of the educational attainment of the family head on

the marginal propensity to consume may reflect the tastes of the

consumption unit. Burk's study [4, p. 121-122] indicated that

household heads with a higher educational attainment had a larger

amount of expenditures on education and reading. The investment

in education for the family's members is usually expensive and over

a limited number of years. Thus, it requires more saving for that

purpose. In addition, it is in general far easier to borrow on the

basis of a tangible physical asset than on the basis of human capital

such as education. Therefore, the families whose head have a

higher educational attainment may need an additional reserve. This

Table 5. Regression coefficients and related statistics of education

equation in the U. S., 1961.

quation

Constant term

Education equation

(4. 10) C1

2435.35

(9.76)**

E1

E2

-1481.23 -1067.28

(-5.80)** (-4.16)**

E3

-546.90

(-2.00)*

0.5924

(21.33)**

E1Y1

E2Y1

E3Y1

0.1130

(3.81)**

0.1086

(3.72)**

0.0683

(2.19)*

R2

0.63

8 years or less:

(4.11) C

1

954.12

(1.90)

0_70S4

(67. 18)**

1368.07

(2.72)**

0.7010

(77.89)**

1888.45

(3.69)**

0.6607

(46.53)**

2435.35

(9.76)**

0.5924

(21.33)**

9 to 12 years:

(4.12) C1

13 to 16 years:

(4.13) C1

17 years or more:

(4.14) C1

where

= money expenditure for current consumption

= disposable money income

E1 =

1,

if 8 years or less of education; = 0, otherwise

E2

1,

if 9 to 12 years of education; = 0, otherwise

E3

1,

if 13 to 16 years of education; = 0, otherwise

** Significant at the 5% level

*

Significant at the 1% level

tj

U)

34

Table t5. Differences in marginal propensities to consume and their t-values for four educational

levels of family head in the U.s., 1961.

8 years

or less

8 years or less

9-12

years

13-16

years

17 years

or more

0

(0)

9-12 years

13-16 years

17 years or more

0.0044

(0.32)

(0)

0.0447

(a.S4)*

0.0403

(2.40)*

0

0. 1130

0. 1086

(3.81)**

(3.72)**

0

(0)

0.0683

(2.19)*

0

(0)

** Significant at the

* Significant at the

may contribute to their low marginal propensity to consume.

From equation (4. 16) to equation (4. 21), one may get the im-

pression that the marginal propensity to consume decreased in gen.-

eral as the age of the family head increased (Table 7). The pattern

observed probably reflects the fact that older families are more

"stocked up" with durables. It seems that there is a tendency for

younger families to make heavy purchases of durable goods even

though they may have to dissave to do so. On the other hand, older

families with necessary assets, may make relatively few durable

goods purchases.

Table 8 indicates that there are no significant differences in

the marginal propensities to consume among the families whose

head is in the age ranges: less than or equal 24 years, 25 to 34

Table 7. Regression coefficients and related statistics of ages equation in the U. S., 1961.

Constant

term

Equation

A1

A2

A3

A4

A5

Y1

A1Y1

A2Y1

A3Y1

A4Y1

A5Y1

Age equation:

(4.15) C1

1038.43 143.42 366.35

(12.03)** (0.64) (2.89)**

343.39

86.84

(2.92)** (0.74)

88.93 0.6102

0.1536 0.1035 0.1082 0.1191 0.0547 0.64

(0.74) (33.35)** (3.34)** (4.39)** (5.07)** (5.56)** (2.43)*

Less than 24 years old:

(4.16) C1

1181.82

(5. 73)**

0.7638

(18. 06)**

25 to 34 years old:

(4.17) C1

1404.78

(15. 08)**

0.7137

1381.82

(17.34)**

0.7184

(65.31)**

1125.27

(14.04)**

0. 7293

(65.12)**

1127.36

(13.50)**

0. 6649

(51. 15)**

1038.43

0.6102

(33.35)**

(47. 90)**

35 to 44 years old:

(4.17) C1

45 to 54 years old:

(4. 10) C1

55 to 64 years old:

(4.20) C1

More than 65 years old:

(4.21) C1

(12.03)**

where

C1 = money expenditure for current consumption

Y1 = disposable money income

= 1, if less than 24 years old; =

0, otherwise

A1

= 1, if 25 to 34 years old; =

otherwise

0,

A2

= 1, if 35 to 44 years old; =

0, otherwise

A3

A

A

=

**

Significant at the 1% level

Significant at the 5% level

*

=

1 if 45 to 54 years old; = 0, otherwise

1 if 55 to 64 years old; = 0, otherwise

U.)

U-'

Table 8. Differences in the marginal propensities to consume and their t-values for six age groups in the U. S., 1961.

24 years

or less

24 years or less

25-34

years

35-44

years

45-54

years

55-64

years

Over

65 years

0

(0)

25-34 years

0.0501

(1.12)

35-44 years

45-54 years

55-64 years

Over 65 years

0

(0)

0. 0454

0. 0047

(1.04

(0.25)

0

(0)

0.0345

0.0156

0.0109

0

(0.79)

(0.84)

(0.69)

(0)

0.0989

(2.24)*

0. 0488

(2.47)*

0.0535

(3.13)**

(3.74)**

0

(0)

0. 1535

0. 1035

0. 1082

0. 1191

0. 0547

0

(3,34)**

(4.39)**

(5.07)**

(5.56)**

(2.43)*

(0)

0. 0644

** Significant at

*

Significant at

C'

37

years, 35 to 44 years, and 45 to 54 years in age. However, the

marginal propensities to consume for the families with age of the

family head in the ranges of 55 to 64 years, and 65 years old or

more, are significantly different from each other.

The marginal propensity to consume is the lowest for families

with 2. 0 to 2. 9 persons and is the highest for the largest families

with 8. 0 or more persons. This gives an indication that the family

with a larger number of members would tend to have a greater

marginal propensity to consume (Table 9).

Crockett and Friends [9, p. 72-92] described the effect of

family size as follows: (1) Most of the effect of family size on

consumption expenditures is reflected in changes in expenditure on

necessary items such as food, clothing, et cetera, and (2) total

consumption goes up markedly as family size increases. Thus, the

high marginal propensity to consume for large families is a result

of total consumption increases as family size increases. With an

increase in expenditures on relatively necessary goods, the family

cannot but decrease expenditures on other commodities and services.

However, this is not easy to achieve because the consumption habit

is relatively rigid. Therefore, a solution to this is to reduce their

saving.

It is then observed from Table 11 that the lowest marginal

propensity to consume occurred in families with a self-employed

Table 9. Regression coefficients and related statistics of family size equation in the U. S., 1961.

Equation

Constant

term

-

F1

F2

F3

F4

F5

F6

F1Y1

F2Y1

F3Y1

F4Y1

F5Y1

F6Y1

R

2

Family size

equation:

(4.22) C1

1010.58 101.66 278.06 436.99 420.96 406.01 582.25 0.7530 -0. 1093 -0.0451 -0.0393 -0.0280 -0.0186 -0.0621 0.64

(S.31)** (0.51) (1.35) (2.08)* (1.89) (1.68) (2.07)* (25.67)**(_3.52)** (-1.42) (-1.23) (-0.84) (-0.52) (-1.50)

2.0 to 2.9

persons:

(4.23) C1

1112.25

(19.50)**

0.6437

(10.82)**

1288.64

(16.31)**

0.7079

(11.82)**

1447.57

(16.05)**

0.7137

(11.90)**

1431.54

(12.29)**

0.7250

(11.91)**

1416.S9

0.7344

(11.79)**

3.0 to 3.9

persons:

(4.24) C1

4.0 to 4.9

persons:

(4.25) C 1

5.0 to 5.9

persons:

(4.26) C1

6.0 to 6.9

persons:

(4.27) C1

(9.44)**

Continued

Table 9--Continued.

Constant

term

Equation

F1

F2

F3

F4

F5

F6

Y1

F1Y

F2Y1

F3Y1

F4Y1

F5Y1

F6Y1

R2

7.0 to 7.9

persons:

1592.83

(7. 70)**

(4.28) C1

0, 6909

(10. 53)**

More than

8.0 persons:

1010.58

(5. 31)**

(4.29) C1

where

money expenditure for current consumption

1

F1

F2

F3

F4

F5

0. 7530

(25. 67)**

=

disposable money income

=

1,

=

1,

=

1,

=

1,

if 40 to 4.9 persons in the family; = 0, otherwise

if 5.0 to 5.9 persons in the family; = 0, otherwise

=

1,

if 6.0 to 6.9 persons in the family;

if 2.0 to 2.9 persons in the family; = 0, otherwise

if 3.0 to 3.9 persons in the family; = 0, otherwise

= 0,

otherwise

= 1,

if 7.0 to 7.9 persons in the family; = 0, otherwise

** Significant at the 1% level

*

Significant at the 5% level

F6

0

Table 10. Differences in the marginal propensities to consume for seven family size groups in the U. S., 1961.

2.0-2.9 persons

2.0-2.9

3.0-3.9

4.0-4.9

5.0-5.9

6.0-6.9

7.0-7.9

Over 8.0

persons

persons:

persons

persons

persons

persons

persons

0

(0)

3.0-3.9 persons

4.0-4.9 persons

5.0-5.9 persons

6.0-6.9 persons

-0.0642

(_4.12)**

-0. 0700

(_4.32)**

(-0.33)

0

(0)

-0. 0813

-0. 0172

-0. 0113

(-0.85)

(-0.54)

0

(0)

-0. 0907

-0. 0436

-0. 0207

0. 0094

0

(-1.80)

(-0.84)

(0.35)

(0)

0. 0170

0. 0228

0. 0341

0. 0435

0

(0.54)

(0.71)

(1.01)

(1.20)

(0)

-0.0451

-0. 0393

-0. 0280

-0. 0186

-0. 0621

0

(-1.42)

(-1.23)

(-0.84)

(-0.52)

(-1.50)

(0)

-0. 0472

(-2.42)*

Over 8 persons

-0. 0058

(_4.25)**

(-3.88)**

7. 0-7.9 persons

0

(0)

-0. 1093

(-3.52)**

** Significant at 1% level

* Significant at 5% level

0

Table 11. Regression coefficients and related statistics of occupation

equation in the U.S., 1961.

Equation

Constant

term

01

02

03

04

O

°6

1

01Y1

02Y1

03Y1 04Y1

05Y1

06Y1

R2

Occupation equation:

(4.30) C1

894.18 734.11 770.07 9.63 213.56

(9.00)** (6.03)** (5.00)**(0.06) (1.43)

162.78 -5.68 0.6950

-0.1440 -0. -120 0.1136 0.0519 0.0590 0.0884 0.64

(1.12) (-0.42)(30.73)** (-5.66)** (-0.45) (3.74)** (1.86) (2.06)* (3.05)**

Self-employed:

(4.31) C1

1628.29

(23.18)**

0.5510

(11.80)**

1664.25

(14.11)**

0.6830

(14.44)**

903.81

(6.41)**

0.8086

(39.83)**

Professional and mgrs.

(4.32) C 1

Clerical and sales:

(4.33) C1

Skilled workers:

(4.34) C1

1107.73

(9.91)**

0.7469

(45.82)**

Semi-skilled workers:

(4.35) C1

1056.95

(8.89)**

0.7540

(43.09)**

888.50

(4.05)**

0.7834

(43.28)**

Unskilled workers:

(4.36) C1

Continued

Table 11--Continued.

Equation

Constant

term

01

°2

03

04

0

°6

y1

01y1

Retired people:

(4.37) C1

894.18

0. 6950

(30. 75)**

(9. 00)**

where

money expenditure for current consumption

disposable money income

0

02 =

03 =

1,

if self-employed; = 0, otherwise

1,

if professional and managers; = 0, otherwise

1,

if clerical and sales; = 0, otherwise

04

1,

if skilled workers; = 0, otherwise

0

1, if semi-skilled workers; = 0, otherwise

1,

if unskilled workers;

** Significant at the 1% level

* Significant at the 5% level.

0, otherwise

02Y1

03Y1

04Y1

05Y1

06Y1

R2

43

family head. The self-employed families save a substantially

high proportion of their income as compared to other occupational

classes. This is true for the self -empl oyed in general. Ownership of a business or professional practice brings about a strong

need for investment funds thus resulting in a high level of saving.

Furthermore, the income of the self-employed family is more

uncertain than that of other occupational classes. Thus, more

money has to be saved for emergency use according to Friedman.

The marginal propensity to consume of self-employed families was significantly different from that of other occupational groups

(Table 12). This is similar to results reported by Friedman [ii]

and by Klein [16]. Friedman estimated that the marginal propensity

to consume for independent business was 0. 54 but it was about 0. 82

for others, using 1948 -50 data. Klein reported, in the 1950 and

1951 survey data for the U.S., the marginal propensity to save for

farmers and business men together was about 0.40-0.45. For nonfarmers and nonbusiness men units, the marginal propensity to save

was 0. 20.

The foregoing analyses indicates that some marginal propensities to consume with respect to socioeconomic variables of fam-

ilies are not significantly different from each other. This provides

a basis on which to group them together. The next step is to

explicitly include them in a multiple regression model. The

Table 12. Differences in the marginal propensities to consume for seven occupational groups in the U. S., 1961.

Selfemployed

Self-employed

Professional

and managers

Clerical

Skilled

and sales

Semiskilled

Unskilled

Retired

0

(0)

Professional and managers

-0. 1320

(-7.29)**

Clerical and sales

Skilled workers

Semi-skilled workers

Unskilled workers

Retired

** Significant at 1% level

* Significant at 5% level

0

(0)

-0. 2576

-0. 1256

0

(-5.06)**

(-2.44)*

(0)

-0. 1959

-0. 0639

0. 0617

0

(3.96)**

(-1.28)

(2.37)*

(0)

-0. 2030

-0. -710

0. 0546

0. 0071

0

(_4.07)**

(-1.41)

(2.04)*

(0.30)

(0)

-0. 2324

-0. 1004

0.0252

-0. 0365

-0. 0294

0

(-4.64)**

(_1.98)*

(0.93)

(-1.50)

(-1.17)

(0)

0.0519

(1,86)

0.0590

(2.06)*

0. 0884

-0. 1440

-0. 0120

0. 1136

(-5.66)**

(-0.45)

(3.74)**

(3.05)**

0

(0)

45

multiple regression equation fitted to the data is presented below.

Farm families equation:

C =ao+a 11

R +a 21

E +a E

32+a A

41+aA52+a5S1

(4.38)

1

+aO

71 +aO

82 +aO

93 +bY

ol +bRY

111 +bEY

211

+ b3E2Y1 + b4AJY1 + b5A2Y1 + b6S1Y1 + b7O1Y1

+ b8O2Y1 + b9O3Y1 + e

Nonfarm families equation:

C1 = a

(4. 39)

+ a'1R1 + a'2E1 + a'3E2 + a'4A1 + a5A2 + a'6S1

+aTO

71 +a'O

82 +a10

01 +b'RY

93 +b'Y

111 +b'EY

211

+ b3E2Y1 + b'4A1Y1 + bt5A2Y1 + b'6S1Y1 + b'701Y1

+ bt802Y1 + b9O3Y1 + e

where

C1

= Money expenditure for current consumption.

Y1

= Money disposable income.

R1

=

1,

if Northcentral and Western regions; = 0, otherwise.

=

1,

if 13 to 16 years of education; = 0, otherwise.

1

if more than 17 years of education, = 0, otherwise.

E2 =

A1 =

1, if the age of family head is 55 to 64 years; = 0,

otherwise.

A2 =

if the age of family head is more than 65 years; = 0,

otherwise.

S1

1,

=

1,

if 2. 0 to 2. 9 persons in the family; = 0, otherwise.

46

0

1,

if self-employed; = 0, otherwise.

02 =

1,

if professional, manager, or retired; = 0, otherwise.

1,

if clerical, sales, or unskilled worker;

03 =

0,

otherwise.

e

= a random error term.

The results obtained using the above equations are given in

Table 13. The impact of the socioeconomic variables of the family

on the marginal propensity to consume is discussed below.

Farm families;

The negative coefficient of the regional variable (-0. 2033)

shows that families in the Northcentral and Western regions have

about 0. 2033 lower marginal propensity to consume than farm fam-

ilies residing in the Northeast and Southern regions. If the family

head has a college education, the marginal propensity to consume

would be decreased about $0. 1340. The negative value of the family

size variable indicates that as the family size decreased to 2. 0 to

2. 9 persons, there is a tendency for the marginal propensity to

consume to decrease. The coefficient for the self-employed vanable is -0. 2076. This indicates that the shift from skilled or semi-

skilled worker to a self-employed occupation would tend to decrease

the marginal propensity to consume by $0. 2076.

47

Table 13.

Multiple regression coefficients and related statistics in farm and n

U.S., 1961.

Regressors

Farm

Nonf arm

families

fanulies

Constant

885.93

(3.02)**

1137.60

(13.08)**

R

1022.75

(6.90)**

(1.28)

E1

1192.77

(3.61)**

638.62

(4.91)**

E

2

1948.41

(2.02)*

1036.97

(4.00)**

-192.46

(-1.04)

-91.75

(-0.78)

-457.48

(-1.95)

-271.17

-1.85)

-64. 13

(-0.37)

-27.50

(-0.29)

-616.15

(2.05)*

1140.55

(7.46)**

1

A

1

A2

S1

o

o

1

.

101.16

137.21

196.67

(0.29)

(1.48)

03

47.35

(0.13)

-291.04

(_2.71)**

Y

0. 7293

(14. 07)**

0. 7789

(58. 05)**

2

R1Y1

E1Y1

E2Y1

A1Y1

A2Y1

-0. 2033

-0. 0234

(-7.22)**

(-2.01)*

-0. 1340

(_2.67)**

(-3.56)**

-0. 1708

-0. 0609

(-1.41)

-0. 1174

(_3.97)**

0.0372

(0.99)

-0.0383

(-2.27)*

0.0602

-0.0759

(-3.15)**

(1.18)

Continued

Table 13--Continued.

Regressors

SY

1

1

01Y1

02Y1

03Y1

R

2

a

Farm

Nonf arm

families

families

-0. 1806

(_4.93)**

-0.0860

(-6.06)**

-0.2076

(-3.92)**

(-7.01)**

-0. 1536

0.0033

-0. 0242

(0.04)

(-1.33)

-0. 0122

0. 0632

(-0.17)

(3.70)**

0.49

0.67

1611

8607

The figures in the parentheses are the t-values.

** Significant at the 1 % level

* Significant at the 5% level

Nonfarm families:

The negative values for regional and educational variables,

suggest that a change to the regions or educational level specified by

the variables result in a tendency for the marginal propensity to consume to decrease. The coefficient of family size is negative and significant. This is the same as that of the farm families equation.

The negative coefficient of the age variables indicates that as the

family head increases in age, the marginal propensity to consume

decreases. The coefficients for all occupational variables are

significant.

49

To test the hypothesis that there are no significant differences in

the marginal propensity to consume of farm and nonfarm families if

they have homogenous characteristics with respect to family size,

the age of family head, the educational level of family head, the

occupation status of family head, and region, one would need to

disaggregate the farm and the nonfarm family samples into sub-

groups with common characteristics of these particular variables.

The procedure used in this study is based on the socioeconomic

variables specified in equation (4. 38). All families which have the

same values for the variables specified are grouped together. As

a result, each of the groups is homogeneous with regard to a set of

socioeconomic variables. Information on the groups with at least

15 observations in the farm and the nonfarm samples is presented

in Table 14.

The distribution of families by selected characteristics of

the families in the farm and nonfarm samples is shown in Table

15.

Eighty-three percent of families in the farm sample lies

in the 17 selected family types; but it constitutes only 46 percent

of the families from the nonfarm sample. The t-test is employed

to test the null hypothesis that this percentage is the same in the

For distribution of families in all groups, see Appendix B.

Table 14. Socioeconomic characteristics of the family in each group.

Group

No.

Region

Socioeconomic characteristics of family within each group

Education level of

Family size

Age of family

family head

head

Occupation of family

head

Less than 12 years

More than 12 years

Less than 12 years

More than 12 years

Less than 12 years

2. 0-2.9 persons

2.0-2.9 persons

2. 0-2.9 persons

4

5

Northcentral and Western

Northcentral and Western

Northcentral and Western

Northcentral and Western

Northcentral and Western

More than 3. 0 persons

More than 3.0 persons

Less than 54 years

55-64 years

More than 65 years

Less than 54 years

Less than 54 years

6

Northcentral and Western

Less than 12 years

Less than 3.0 persons

Less than 54 years

7

8

9

10

11

Less than 12 years

13-16 years

Less than 12 years

Less than 12 years

Less than 12 years

Less than 12 years

Less than 12 years

More than 3. 0 persons

More than 3.0 persons

2. 0-2.9 persons

13

Northcentral and Western

Northcentral and Western

Northeast and Southern

Northeast and Southern

Northeast and Southern

Northeast and Southern

Northeast and Southern

More than 3. 0 persons

Less than 3. 0 persons

55-64 years

Less than 54 years

Less than 54 years

55-64 years

More than 65 years

Less than 54 years

Less than 54 years

14

Northeast and Southern

Less than 12 years

More than 3. 0 persons

Less than 54 years

15

Northeast and Southern

Less than 12 years

More than 3. 0 persons

Less than 54 years

Self-employed

Self-employed

Self-employed

Self-employed

Self-employed

Self-employed

Professional and managers

and retired

Clerical and sales and

unskilled workers

Skilled and semi-skilled

16

17

Northeast and Southern

Northeast and Southern

Less than 12 years

13-16 years

More than 3.0 persons

More than 3.0 persons

55-64 years

Less than 54 years

Self-employed

Self-employed

1

2

3

12

Self-employed

Self-employed

Self-employed

Self-employed

Clerical and sales and

unskilled workers

Skilled and semi-skilled

workers

2.0-2.9 persons

2.0-2.9 persons

workers

01

0

51

Table 15. Distribution of families in the farm and the nonfarrn samples by characteristics of

the family.

Group a/

No.

Farm families

Observed

1

50

2

69

41

318

51

3

4

5

6

7

Expected

44

64

8

28

51

79

9

10

11

50

244

20

12

13

14

15

16

77

78

69

17

17

Nonfarm families

Observed

Expected

(21)

(25)

(14)

33

(119)

(124)

(256)

148

446

961

(347)

(363)

(749)

(22)

21

(63)

17)

40

27

29

25

(

30

15

(20)

(28)

(19)

(101)

61)

(185)

(290)

(297)

(180)

(543)

(848)

(69)

24

37

14)

(

No. of families in

17 selected groups

r1 = 1, 340

r2 = 3, 922

Total families in the sample

n1

1,611

= 8, 607

Percent in 17 selected groups

P

r

1

n

P2 =-n

100=83

= 100 - P1 = 17

s12

2

1

Farm families: (Obs. - Exp.) /Ecp. = 2010. 66

Nonf arm families:

(Ohs. - Exp. )2/Exp. 529.05

2

x

2

01

= 32.00, d. f. = 16

For description of the group, see Table 14.

S22 = P292/n2 = 0.289

= 48.68**, d.f. = 10216

n1

x = 2010.66 + 529.05 = 2539. 71**

100= 46

Q2 = 100 - P2 =

P191/n1 = 0.876

51)

(58)

(80)

(56)

1,060

(24)

(

(

154

221

651

(

(62)

(74)

(42)

40)

52

two samples. The calculated t-value is 48. 68. This is significant

at the one percent level with the degrees of freedom being 10216.

Thus, the null hypothesis is rejected. This implies that the distribution of families in the farm sample by family types is different

from that of the nonfarm sample. It can be easily observed from

the table that most of the farm families have the socioeconomic

characteristics of groups 4 and 12, while most of the nonfarm

families have Number 6 and 15 group& characteristics.

One may also want to know whether the distribution of farm

families within the 17 selected family types is different from that

of the nonfarm sample. To investigate this question, we set up the

null nypothesis: both farm and nonfarm families in the 17 selected

groups have the same probability distribution. For the one percent

level of significance, the critical X2 value is 32. 00 which is less

than the calculated X2 value of 2539. 71. Thus, we reject the null

hypothesis and conclude that farm and nonfarm families in the 17

selected family types have significantly different distributions.

The consumption function for each group is presented in

Table 16. The t-test is used to test the quality of the marginal

propensity to consume between farm ar*d nonfarm families. The

results of testing is presented in the last column of the table.

One noticeable result is that most farm and nonfarm families

with similar characteristics have no significant differences in their

Table 16. Consumption functions and related statistics for selected homogeneous groups of farm and nonfarm families in the U. S.,

1961.

Group

No.

1

2

3

4

Farm families

1228.40+0.1378 Y

(2.57)* (1.58) 1

C1= 1035.94+0. 1750 Y1

(2.02)* (1.84)

C1 = 770.92 + 0.1980 Y1

(1.45)

(1.96)*

C1 =

C

1

S

6

7

= V292. 53 +

(2.90)**

0.3184 Y

(4.02)**1

C1=1956.03+0.5138Y1

(3.97)** (5.56)**

C1= 1908.69+0.5260Y1

(5.81)** (8.92)**

C1= 1100.07+0.3556Y1

(2.28)* (4.06)**

8

C1=2485.30+0.1844Y1

9

C1 = 205.64 + 0.3411

(4.48)**

(1.96)*

(.45)

10

11

12

(4.12)**

C1= 13. 19+ ).3783Y1

(0.03)

(4.17)**

C1= -251.83+0.4013Y

(4.13)**1

(-.49)

C1=269.78+0.5217Y1

(.64)

(7.04)**

Nonfarm families

C1 = 2351.81 + 0.5159 Y1

(10.97)** (16.33)**

C1=2260.06-f-0.4776Y1

(9.23)** (13.34)**

C1 = 2080.64 + 0.4400 Y1

(8.01)** (11.08)**

C1 = 2379.30 + 0.6019 Y1

(12.23)** (21.34)**

C1 = 947.72 + 0.8187

(5.95)** (33.15)**

C1 = 1238.76 + 0.7555

(10.52)** (42.44)**

C1 = 2287.55 + 0. 5636 y

(I0.12)** (17.13}**

C1= 3017.93+0.5410Y1

(12.97)** (16.39)**

C1 = 2250.65 + 0. 5393 Y1

(11.29)** (18.34)**

= 2158.90 + 0.5010

(9.32)** (14.78)**

C1= 1979.48+0.4634Y1

(8.00)** (12.20)**

C1 = 2278.14+ 0.6253 Y1

(12.95)** (19.42)**

Differences of MPC1 between farm

and nonfarm families

0.3781

(4.06).4°K

0.3026

(2.97)**

0. 2420

(2.22)*

0.2835

(3.36)**

0.3049

(3.18)**

0.2295

(3.71)**

0.2080

(2.22)*

0.3566

(3.57)*

0. 1982

(1.90)

0. 1227

(1.26)

0.0621

(.59)

0.1036

(1.32)

Continued

Ui

Table 16--Continued.

Group

No.

13

Farm families

C1=1023.14+0.7326Y

(1.83)

14