The Effe ctiv e Provi sio

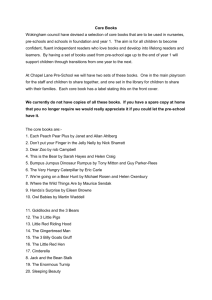

advertisement