ARCLG140: Conservation in practice: Preventive conservation Course handbook 2015 - 2016

advertisement

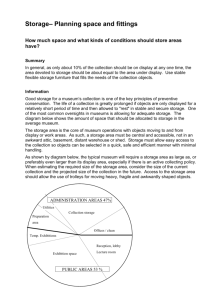

ARCLG140: Conservation in practice: Preventive conservation Course handbook 2015 - 2016 Co-ordinator: James Hales j.hales@ucl.ac.uk Room: 403A Telephone number: 02076794728 1 ARCLG140: Conservation in practice: preventive conservation 2015-16 MA Principles of Conservation core course: 15 credits Co-ordinator: James Hales j.hales@ucl.ac.uk Room: 403A Telephone number: 02076794728 Turnitin Class ID: 2970991 Turnitin Password IoA1516 Please see the last page of this document for important information about submission and marking procedures, or links to the relevant webpages. 1 OVERVIEW Short description The aim of this course is to provide a wide-ranging and challenging introduction to preventive conservation. The course is concerned primarily with the care of objects and artifacts as opposed to structures and sites, and provides an introduction to environmental management and practical aspects of preventive conservation such as Integrated Pest Management, pollution and environmental monitoring and micro-climate control. Week-by-week summary th Week 1 – 8 October. 9.00 – 11.00 Course introduction and overview th Week 2 - 15 October. 9.00 – 11.00 Relative humidity: is control of relative humidity really necessary? nd Week 3 – 22 October. 9.00 – 11.00 Damage due to visible and ultraviolet light th Week 4 – 29 October. Handling, packaging 9.00 – 11.00 th 9.00 – 11.00 Week 5 – 5 November. Transport and display th 12 November. READING WEEK (NO TEACHING) Week 6 - 19 November. Pollution th 9.00 – 11.00 th 9.00 – 11.00 Week 7 - 26 November. Preventing insect damage Week 8 – 3rd December. 9.00 – 11.00 Showcase design and microclimates th Week 9 - 10 December. Disaster Planning th Week 10 - 17 December. Visit to Museum of London 9.00 – 11.00 10.00 – 12.00 2 3 Methods of assessment This course is assessed by one piece of written coursework totalling 4000 words. The topic and deadline for the assessment are specified below. If students are unclear about the nature of the assignment, they should contact the Course Co-ordinator. The Course Coordinator will be willing to discuss an outline of their approach to the assessment, provided this is planned suitably in advance of the submission date. Teaching methods The course is taught by lectures, workshops, demonstrations and visits. The lecture sessions take place in room 209 between 09.00 and 11.00 on Thursdays. Each session has recommended readings, which you will be expected to have read in advance so that you can follow discussion of the topic and contribute actively to it. In most weeks, there will also be a regular seminar for which we will split into smaller groups. Seminars will take place in room B13 (in the basement) at the following times: Thursday: 13.00 – 14.00 14.00 – 15.00 15.00 – 16.00 Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Workload There will be 20 hours of lectures and 8 hours of seminar sessions for this course. Students will be expected to undertake around 62 hours of reading for the course, plus 60 hours preparing for and producing the assessed work. This adds up to a total workload of some 150 hours for the course. Prerequisites There are no prerequisites for the course. Nonetheless, if you want to expand your knowledge of particular topics, you are welcome to attend (but not be assessed for) any undergraduate or Master’s course in the Institute, provided you have the agreement of the course’s coordinator. The lectures will contain technical and scientific content and as such basic knowledge of physics and chemistry would be an advantage, however it is intended that the course should be comprehensible to students of any background. 2 AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND ASSESSMENT Aims Over recent years, the emphasis in conservation has turned increasingly from remedial conservation (putting right what has gone wrong in the past) to preventive conservation (making sure that things do not go wrong in the future). This shift in emphasis has been evident in both objects conservation and site conservation. The course aims to provide a wide-ranging and challenging introduction to preventive conservation. The course is concerned primarily, but not exclusively, with archaeological objects, as opposed to structures and sites. It provides an introduction to environmental management and to some of the practical aspects of preventive conservation. It also examines some of the underlying issues, such as the appropriateness and feasibility of prescriptive guidelines for environmental control. 4 Objectives On successful completion of this course a student should: • be aware of the main processes by which archaeological and ethnographic objects deteriorate, whether within the museum environment in storage or on display • know how to stabilise objects by the control of their environment • be able to define a viable set of environmental parameters for a wide range of material types and operational contexts • be able to monitor the environment in a gallery, storeroom or show case, and make recommendations for implementing any necessary improvements. Learning Outcomes On successful completion of the course students should be able to demonstrate/have developed an ability to: • critically analyse numerical data and be aware of its significance • present reports summarising quantitative data • undertake critical analysis of diverse literature • be able to understand the implications of guidance documents (such as PAS 198) in order to communicate their significance to others and act upon their recommendations. Coursework Assessment tasks Environmental Monitoring Project report 4000 words We will deploy monitoring equipment, and collect data in order to assess the environment provided by an area used for collections storage or display. Once data has been collected you will write a report presenting relevant data and summarising your findings. A specific brief related to the scope of the project and the aims will be provided. We will be discussing the nature of the assignment both in class and in seminars, specific details and resources will also be provided via the Moodle site. If students are unclear about the nature of an assignment, they should discuss this with the Course Co-ordinator. Students are not permitted to re-write and re-submit essays in order to try to improve their marks. However, students may be permitted, in advance of the deadline, to submit for comment a brief outline of the assignment. The nature of the assignment and possible approaches to it will be discussed in class, in advance of the submission deadline. The completed work should be handed in no later than: 11th January 2016 5 Word counts The word count for this piece of assessment is (3,800 - 4,200) The following should not be included in the word-count: title page, contents pages, lists of figure and tables, abstract, preface, acknowledgements, bibliography, lists of references, captions and contents of tables and figures, appendices. Penalties will only be imposed if you exceed the upper figure in the range. There is no penalty for using fewer words than the lower figure in the range: the lower figure is simply for your guidance to indicate the sort of length that is expected. 3 SCHEDULE AND SYLLABUS Teaching schedule Lectures will normally be held 9.00-11:00 on Thursdays, in room 209. Seminars will take place in B13 (in the basement) on Thursday afternoons. There will be three time slots available and at the beginning of term we will sort you into appropriate groups. Tutorial times will be Thursday (room B13) 13.00 – 14.00 14.00 – 15.00 15.00 – 16.00 Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 To keep tutorial groups small enough for effective discussion, it is essential that students attend the group to which they have been assigned. If they need to attend a different group for a particular session, they should arrange to swap with another student from that group, and confirm this arrangement with the course co-ordinator. 6 SEMINAR TIMETABLE We will not start seminars until week 2 and there will be no seminar in the final week (week 10) of term. Please see the timetable below. Week 2 - 15th October. RH monitoring equipment: use, deployment and calibration Week 3 – 22nd October. Risk all together the British Museum Week 4 – 29th October. Light monitoring equipment use and deployment Week 5 – 5th November. Handling objects 12th November. READING WEEK (NO TEACHING) Week 6 - 19th November. The “Oddy” test Week 7 - 26th November. IPM and Pests Week 8 – 3rd December. Looking at environmental monitoring data Week 9 - 10th December. Presenting environmental monitoring data Syllabus The course starts with an introduction to the concept of preventive conservation, and then goes on to look at some of the ways in which damage to museum objects can be minimised or prevented. It does not deal directly with techniques of remedial conservation. At the end of the course, we look at the cost effectiveness of preventive conservation and at disaster planning – an important aspect of preventive conservation but one which is not always associated with it. The following is a session outline for the course as a whole, and identifies essential and supplementary readings relevant to each session. Information is provided as to where in the UCL library system individual readings are available; their location and Teaching Collection (TC) number, and status (whether out on loan) can also be accessed on the eUCLid computer catalogue system. Readings indicated with an asterisk (*) are particularly relevant, and it is expected that you will have read at least some of these prior to the session under which they are listed. When an entire book is suggested, dip into it for the bits you find most helpful. 7 8th Oct. 1: course introduction and overview (James Hales) The session will start with an introduction to the concept of preventive conservation, stressing the numerous dangers to which cultural heritage is exposed, and looking at possible preventive measures. Reading – preventive conservation in general * Pye, E M, 2001. Issues in practice: conservation procedures. In Caring for the Past: Issues in Conservation for Archaeology and Museums. 121-132. L PYE. * Padfield T, 2005. How to keep for a while what you want to keep for ever. www.padfield.org/tim/cfys/phdk/phdk_tp.pdf Museum Handbook, Part 1: Museum Collections (web edition). http://www.nps.gov/history/museum/publications/MHI/CHAPTER4.pdf See, in particular, Chapter 4: Museum Collections Environment. • Corr, S., 2000. Caring for collections: a manual of preventive conservation. Dublin: The Heritage Council of Ireland. L COR Bradley S, 2005. Preventive conservation research and practice at the British Museum. Journal of the American Institute of Conservation (44) 159-173. Roy A and Smith P (eds), 1994. Preventive Conservation: Practice, Theory and Research. Preprints of the IIC Ottawa Congress, 12-16 September 1994. London: International Institute for Conservation Getty Conservation Institute, 2004. Conservation, the GCI Newsletter. 19 (1). Special issue on preventive conservation. The Heritage Health Index. http://www.heritagepreservation.org/HHI/news.html. See link to article in the New York Times on 6 December 2005, ‘History is slipping away as collections deteriorate’. Padfield T. Conservation physics. www.padfield.org/tim/cfys/ Contains many useful articles, some lighthearted. 15th October. 2: Relative humidity: is control of relative humidity really necessary? (James Hales) Controlling the amount of moisture in the air is one of the mainstays of preventive conservation in museums. We will examine the concepts of absolute humidity and relative humidity, and their significance in the care of objects. Following the publication of Thomson’s book on the museum environment, many conservators attempted to follow his recommendations slavishly. In recent years, the need for tight guidelines has been questioned increasingly. We will discuss the need for RH control in the light of recent experience, and we will then go on to look at methods of RH measurement and control. Reading * Thomson, G., 1986 (2nd edn). The Museum Environment. London: Butterworths. 66-127. MD 3 THO #. Also ARCHITECTURE G 97.7 THO * De Guichen G, 1988. Climate in Museums. Rome: ICCROM. MD 3 DEG 8 Camuffo, D, 1998. Developments in Atmospheric Science 23: Microclimate for cultural heritage. Amsterdam: Elsevier. LA1 CAM * Staniforth S, 1992. Control and measurement of the environment. In Manual of Curatorship (ed Thompson, J M A). London: Butterworth-Heinemann. 234-245. M 2 THO # * Ashley-Smith, J, Umney N and Ford, D, 1994. Let’s be honest - realistic environmental parameters for loaned objects. In Roy, A and Smith, P (eds), 1994. Preventive conservation: practice, theory and research. Preprints of the Ottawa Congress, 12-16 Sept 1994. London: International Institute for Conservation. 28-31. LA IIC * Erhardt D and Mecklenburg M, 1994. Relative humidity re-examined. In Roy, A and Smith, P (eds), 1994. Preventive conservation: practice, theory and research. Preprints of the Ottawa Congress, 12-16 Sept 1994. London: International Institute for Conservation. 32-38. LA IIC * Brown J P & W B Rose 1997. Development of humidity recommendations in museums and moisture control in buildings. http://palimpsest.stanford.edu/byauth/brownjp/humidity1997.html * Museums and Galleries Commission, 1993. Managing your Museum Environment. London: Museums and Galleries Commission. TEACHING COLLECTION 2283 Cassar, M., 1994. Environmental management : guidelines for museums and galleries. London : Routledge. MD 3 CAS Cassar M and Hutchings J, 2000. Relative humidity and temperature pattern book: a guide to understanding and using data on the museum environment. London: Museums and Galleries Commission. MD3 CAS Brown, J P, 1993. What can psychrometric data tell us? In Electronic environmental monitoring in museums (ed Child, R). London: Archetype Publications. 37-59. MD 3 CHI Florian, M-L E, 2002. Fungal facts: solving fungal problems in heritage collections. London: Archetype. MD3 FLO. 22nd October. 3: damage due to visible and ultraviolet light (James Hales) Light can be very damaging to museum objects, causing changes to both colour and structure. We will look at the effects of ultra-violet and visible light, at ways of measuring light intensity, and at some of the ways in which light damage can be limited. Reading *Thomson, G., 1986 (2nd edn). The Museum Environment. London: Butterworths. 2-64. MD 3 THO #. Also ARCHITECTURE G 97.7 THO *Ashley-Smith J, 2000. Museum lighting – who is it for? Museum Practice (14) 46-8. *Ashley-Smith J, 1999. Risk assessment for object conservation. Ch,12: Light entertainment. 226-245. L ASH # Brommelle N S, 1964. The Russell and Abney Report on the action of light on water colours. Studies in Conservation, 9, 140-149. Schaeffer T T, 2001. Effects of light on materials in collections: data on photoflash and related sources. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. LA Qto SCH European Union (n.d.) Shedding light on cultural heritage. http://ec.europa.eu/research/environment/newsanddoc/article_1704_en.htm#1 LightCheck (n.d.). www.lightcheck.co.uk 9 Römich H., Martin G., Lavedrine B. and Bacci M, 2004. LightCheck®: A New Tool in Preventive Conservation. V&A Conservation Journal (47) 17-18. Also available at www.vam.ac.uk/res_cons/conservation/journal/number_47/lightcheck/index.html Staniforth S, Light and environmental measurement in National Trust houses. In Knell, S. (ed) Care of collections. London: Routledge. 117-122 L KNE* 29th October. 4: handling, packaging (James Hales) Incorrect handling is one of the greatest threats to museum objects. Dropping an object can do far more damage, far more quickly, than years of inappropriate RH or light levels. In this session I will introduce safe procedures for handling objects, whether they are being conserved, studied, transported or displayed. Reading Stolow N., 1987. Conservation and exhibitions: packing, transport, storage and environmental considerations. London: Butterworths. ME3 STO # nd Watkinson D and Neal V, 1998. First aid for finds (2 edn). Hertford and London: British Archaeological Trust, Archaeology Section of UKIC, and the Museum of London. LA Qto WAT Rose C.R. and de Torres A R, 1992. Storage of natural history collections: ideas and practical solutions. Pittsburgh, PA: Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections. MG 1 ROS Museum Handbook, Part 1: Museum Collections (web edition). www.cr.nps.gov/museum/publications/MHI/mushbkI.html. Chapter 6: Handling, packing and shipping. 5th November. 5: Transport and Display Following on from our session on handling and packing, we will talk about the logistics of transporting objects and how to mitigate against the agents of deterioration while objects are on display. Reading Stolow N., 1987. Conservation and exhibitions: packing, transport, storage and environmental considerations. London: Butterworths. ME3 STO # nd Watkinson D and Neal V, 1998. First aid for finds (2 edn). Hertford and London: British Archaeological Trust, Archaeology Section of UKIC, and the Museum of London. LA Qto WAT Rose C.R. and de Torres A R, 1992. Storage of natural history collections: ideas and practical solutions. Pittsburgh, PA: Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections. MG 1 ROS Museum Handbook, Part 1: Museum Collections (web edition). www.cr.nps.gov/museum/publications/MHI/mushbkI.html. Chapter 6: Handling, packing and shipping. 12th November. No session (reading week) 19th November. 6: Pollution (James Hales) Air-borne pollutants, whether particulate or gaseous, can have very serious effects on museum collections. In some cases, such as collections of molluscs, the collection can be completely destroyed by pollution. Even in less dramatic cases, objects may become irreversibly soiled or weakened, or corroded. 10 The pollutants may come from outside the museum (eg SO2 and NOx from combustion processes), from the showcase materials (eg CH3COOH and HCHO from wood or manufactured boards), or even from the objects themselves (eg H2S from wool). Nigel Blades, from the National Trust will describe procedures for monitoring pollutants in museums, and will demonstrate some of the passive monitors that are frequently employed. Reading: * Blades, N, Oreszczyn, T, Bordass, B and Cassar, M, 2000. Guidelines on pollution control in museum buildings. London: Museums Association. MD3 BLA # (See also updated version at http://eprints.ucl.ac.uk/2443/1/2443.pdf) * Hatchfield P, 2002. Pollutants in the museum environment – practical strategies for problem solving in design, exhibition and storage. London: Archetype. MD3 HAT. * Tétreault, J., 2003. Airborne pollutants in museums, galleries and archives: risk assessment, control strategies, and preservation management. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute. MD3 TET. Brimblecombe P (ed), 2003. The effects of air pollution on the built environment. London: Imperial College Press. KP1 BRI Thomson, G., 1986 (2nd edn). The Museum Environment. London: Butterworths. 130-162. MD 3 THO #. Also ARCHITECTURE G 97.7 THO Grzywacz C M and Tennent N H, 1994. Pollution monitoring in storage and display cabinets: carbonyl pollutant levels in relation to artifact deterioration. In Roy, A and Smith, P (eds), 1994. Preventive conservation: practice, theory and research. Preprints of the Ottawa Congress, 12-16 Sept 1994. London: International Institute for Conservation. 164-170. LA IIC Grzywacz C M, 2006. Monitoring for gaseous pollutants in museum environments. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. MD3 GRZ. Lee L R and Thickett D, 1996. Selection of materials for the storage or display of museum objects. British Museum Occasional Paper 111. London: British Museum. LA Qto LEE Green, L.R. and Thickett, D, 1995. Testing materials for use in the storage and display of antiquities - a revised methodology. Studies in Conservation 40 (3) 145-152 Robinet L and Thickett D, 2003. A new methodology for accelerated corrosion testing. Studies in Conservation 48 (4) 263-8. www.ucl.ac.uk/sustainableheritage/impact/ The IMPACT pollution model can be downloaded from this site. 26th November. 7: Preventing insect damage (James Hales) Insects can devastate museum collections alarmingly quickly. This session will give an overview of the damage that can be caused, and of strategies for insect control. Reading * Pinniger, D. 2008. Pest management: a practical guide. Cambridge: Collections Trust. MD 3 Qto PIN * Pinniger, D, 2001. Pest management in museums, archives and historic houses. London: Archetype. MD3 PIN. Florian, M-L, 1997. Heritage Eaters: insects and fungi in heritage collections. London: James & James. MD3 Qto FLO 11 Kingsley H et al, 2001. 2001 a Pest Odyssey: Integrated pest management for collections: proceedings of a joint conference of English Heritage, the Science Museum and the National Preservation Office. London : James & James. MD3 Qto KIN. Daniel, V (ed) 2003. Papers from the 5th International Conference on Biodeterioration of Cultural Property, Sydney, 2001. Bulletin of the Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material (28). Also available on www.amonline.net.au/pdf/ICBCP5_papers.pdf. Selwitz C and Maekawa S, 1998. Inert gases in the control of museum insect pests. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. MD3 SEL and ARCHIVES QUARTOS K 11 SEL (main library). 3rd December. 8: showcase design and microclimates (James Hales) Showcases play an important role in preventive conservation. They allow for the creation of a micro-climate that is suitable for the objects inside, and they facilitate display and security. On the other hand, they can serve to trap in pollutants originating from the showcase materials or from the objects themselves. Is it better for showcases to be air-tight or to leak a little? And how do we select safe materials for the construction of the case? Reading The Fitzwilliam Museum. www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk Follow links for the Ancient Egypt project. Ambrose T and Paine C, 1993. Museum basics. Unit 23: Museum Showcases. London: ICOM/Routledge. 82-4. M5 AMB # Ganiaris H and Sully D, 1998. Showcase construction: materials and methods used at the Museum of London. The Conservator (22) 57-67. Cassar, M., 1994. The environmental performance of showcases. In Roy, A and Smith, P (eds), 1994. Preventive conservation: practice, theory and research. Preprints of the Ottawa Congress, 12-16 Sept 1994. London: International Institute for Conservation. 171-173. LA IIC Stanley B, Xavier-Rowe A and Knight B, 2003. Displaying the Wernher Collection: a pragmatic approach to display cases. The Conservator (27) 34-46 10th December. 9: Disaster Planning (James Hales) Whilst incorrect humidity levels, insects and pollution can have serious impacts on a collection, there is nothing quite like a disaster for destroying an entire collection within a matter of a few hours. It is irresponsible to pretend that a disaster can never happen, and conservators have a role to play in drawing up plans to deal with emergencies such as floods, fires and earthquakes. Which objects should be rescued first? Where will you take them? How will you dry them all out? Reading * Anon, 2005. Working Knowledge: Emergency Planning. Museum Practice (Spring 2005). 43-59. INST ARCH Pers. Anon, 2006. Field Guide to Emergency Response. Washington DC: Heritage Preservation Inc. INST ARCH MD 9 LON * Hunter, J 1994. Museum Disaster Preparedness Planning. In Knell, S. (ed) Care of collections. London: Routledge. 246-261. L KNE* 12 East Midlands Museums Service Regional Emergencies and Disaster Squad, 1991. Museum & records office emergency manual. Nottingham: East Midlands Museums Service. MD 9 Qto EMM Jones B G 1994 Experiencing Loss. In Knell, S. (ed) Care of collections. London: Routledge. 240-5. L KNE* Dorge V and Jones S, 1999. Building a disaster plan. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. MD 9 DOR The Emergency Response and Salvage Wheel: www.heritagepreservation.org/catalog/Wheel1.htm www.neh.gov/news/archive/19970611.html www.getty.edu/conservation/publications/newsletters/12_2/gcinews4.html 17th December. 10: Visit to Museum of London We will visit the museum of London to see how they have approached the problems of storage and display over the past twenty years. Due to the timing of the visit and the fact that we will be off-site some students may find they have clashes with other classes during this time – I understand that not all students will be able to attend and therefore attendance on the visit is not mandatory. 4 ONLINE RESOURCES The full UCL Institute of Archaeology coursework guidelines are given here: https://wiki.ucl.ac.uk/display/archadmin/Students The full text of this handbook is also available at the link above (or the Moodle site described below) Moodle There is a Moodle course associated with this core unit, please make sure you sign up so that you can benefit from the extra resources available in this location. The course title is as follows: ARCLG140: Conservation in Practice: Preventive Conservation and you can log in to the Moodle system here: https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/login/ The online reading list for this course is available through the Moodle site. 5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Libraries and other resources In addition to the Library of the Institute of Archaeology, other libraries in UCL with holdings of particular relevance to this course are: Science library, DMS Watson Building, Malet Place, London, WC1E 6BT Libraries outside of UCL which have holdings which may also be relevant to this degree are: 13 The British Museum Conservation Department Library to which you are admitted as a conservation student of this institute (see separate leaflet on access to, and rules for the use of, this library). There are many web sites and discussion lists that are relevant to conservation and cultural heritage. It is impossible to list them all, but you may like to explore the following before long: http://palimpsest.stanford.edu CoOL: Conservation on Line www.bcin.ca Conservation Bibliographic Database, BCIN www.aata.getty.edu/NPS/ Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts http://www.getty.edu/conservation/ The Getty Conservation Institute http://www.cci-icc.gc.ca/ Canadian Conservation Institute Information for intercollegiate and interdepartmental students Students enrolled in Departments outside the Institute should obtain the Institute’s coursework guidelines from Judy Medrington (email j.medrington@ucl.ac.uk), which will also be available on the IoA website. Health and safety (if applicable) The Institute has a Health and Safety policy and code of practice which provides guidance on laboratory work, etc. This is revised annually and the new edition will be issued in due course . All work undertaken in the Institute is governed by these guidelines and students have a duty to be aware of them and to adhere to them at all times. ***************************** 14 ___________________________ APPENDIX A: POLICIES AND PROCEDURES 2014-15 (PLEASE READ CAREFULLY) This appendix provides a short précis of policies and procedures relating to courses. It is not a substitute for the full documentation, with which all students should become familiar. For full information on Institute policies and procedures, see the following website: http://wiki.ucl.ac.uk/display/archadmin For UCL policies and procedures, see the Academic Regulations and the UCL Academic Manual: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/srs/academic-regulations ; http://www.ucl.ac.uk/academic-manual/ GENERAL MATTERS ATTENDANCE: A minimum attendance of 70% is required, except in case of illness or other adverse circumstances which are supported by medical certificates or other documentation. A register will be taken at each class. If you are unable to attend a class, please notify the lecturer by email. DYSLEXIA: If you have dyslexia or any other disability, please discuss with your lecturers whether there is any way in which they can help you. Students with dyslexia should indicate it on each coursework cover sheet. COURSEWORK SUBMISSION PROCEDURES: You must submit a hardcopy of coursework to the Co-ordinator's pigeon-hole via the Red Essay Box at Reception (or, in the case of first year undergraduate work, to room 411a) by stated deadlines. Coursework must be stapled to a completed coversheet (available from IoA website; the rack outside Room 411A; or the Library). You should put your Candidate Number (a 5 digit alphanumeric code, found on Portico. Please note that this number changes each year) and Course Code on all coursework. It is also essential that you put your Candidate Number at the start of the title line on Turnitin, followed by the short title of the coursework (example: YBPR6 Funerary practices). LATE SUBMISSION: Late submission is penalized in accordance with UCL regulations, unless prior permission for late submission has been granted and an Extension Request Form (ERF) completed (see below). The penalties are as follows: i) A penalty of 5 percentage marks should be applied to coursework submitted the calendar day after the deadline (calendar day 1); ii) A penalty of 15 percentage marks should be applied to coursework submitted on calendar day 2 after the deadline through to calendar day 7; iii) A mark of zero should be recorded for coursework submitted on calendar day 8 after the deadline through to the end of the second week of third term. Nevertheless, the assessment will be considered to be complete provided the coursework contains material than can be assessed; iv) Coursework submitted after the end of the second week of third term will not be marked and the assessment will be incomplete. EXTENSION REQUEST New UCL-wide regulations with regard to the granting of extensions for coursework have been introduced with effect from the 2015-16 session. Full details will be circulated to all students and will be made available on the IoA intranet. Note that Course Coordinators are no longer permitted to grant extensions. All requests for extensions must be submitted on a new UCL form, together with supporting documentation, via Judy Medrington’s office and will then be referred on for consideration. Please be aware that the grounds that are now acceptable are limited. Those with long-term difficulties should contact UCL Student Disability Services to make special arrangements. TURNITIN: Date-stamping is via Turnitin, so in addition to submitting hard copy, you must also submit your work to Turnitin by midnight on the deadline day. If you have questions or problems with Turnitin, contact ioaturnitin@ucl.ac.uk. RETURN OF COURSEWORK AND RESUBMISSION: You should receive your marked coursework within four calendar weeks of the submission deadline. If you do not receive your work within this period, or a written explanation, notify the Academic Administrator. When your marked essay is returned to you, return it to the Course Co-ordinator within two weeks. You must retain a copy of all coursework submitted. WORD LENGTH: Essay word-lengths are normally expressed in terms of a recommended range. Not included in the word count are the bibliography, appendices, tables, graphs, captions to figures, tables, graphs. You must indicate word length (minus exclusions) on the cover sheet. Exceeding the maximum word-length expressed for the essay will be penalized in accordance with UCL penalties for over-length work. CITING OF SOURCES and AVOIDING PLAGIARISM: Coursework must be expressed in your own words, citing the exact source (author, date and page number; website address if applicable) of any ideas, information, diagrams, etc., that are taken from the work of others. This applies to all media (books, articles, websites, images, figures, etc.). Any direct quotations from the work of others must be indicated as such by being placed between quotation marks. Plagiarism 15 is a very serious irregularity, which can carry heavy penalties. It is your responsibility to abide by requirements for presentation, referencing and avoidance of plagiarism. Make sure you understand definitions of plagiarism and the procedures and penalties as detailed in UCL regulations: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/current-students/guidelines/plagiarism RESOURCES MOODLE: Please ensure you are signed up to the course on Moodle. For help with Moodle, please contact Nicola Cockerton, Room 411a (nicola.cockerton@ucl.ac.uk). 16