Systematic review of combination DMARD therapy in rheumatoid arthritis

advertisement

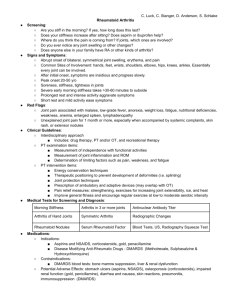

Systematic review of combination DMARD therapy in rheumatoid arthritis Beusekom I. van1, C. MacLean2, C.F. Allaart3, and F.C. Breedveld3. October 2000 RE-2000.14 1) RAND Europe, Leiden, The Netherlands 2) RAND, UCLA school of medicine 3) Leiden University Medical Centre 63 64 CONTENTS List of abbreviations 66 Introduction 67 Systematic review of combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis 71 Results 73 Summary of reviews on combination DMARD therapy 79 Appendix A: Weighted mean differences between DMARD and placebo 82 Appendix B: Adverse effects of selected disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) 84 References 86 Data abstraction tables 97 TABLES AND FIGURES: Table 1. Search terms used for electronic databases 71 Figure 1. Assessing the Jadad score 72 Figure 2. Literature retrieval flow chart 73 Table 2. Characteristics of eligible clinical trials of combination DMARD therapy in rheumatoid arthritis 75 Table 3. Characteristics and findings of published reviews on combination DMARD therapy in rheumatoid arthritis 80 65 List of abbreviations ACR AUR AZA Buc. CQ CRP CSA DAS D-pen DPS Etan. ESR GST HCQ IFX Leflu MP MTX NR Plac. Predn. RAI RAM RF SSA TNF American College of Rheumatology Auranofin Azathioprine Bucillamine Chloroquine C-reactive Protein Cyclosporine Disease Activity Score D-penicillamine Dapsone Etanercept Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate Gold Sodium Thiomulate Hydroxychloroquine Infliximab Leflunomide (Pulsed) Methylprednisolone Methotrexate Not reported Placebo Prednisone/ prednisolone Ritchie Articular Index RAND Appropriateness Method Rheumatoid Factor Sulphasalazine Tumor Necrosis Factor 66 INTRODUCTION Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic autoimmune disease of unknown aetiology. The most striking symptom is a chronic, symmetric synovitis of peripheral joints. Up to 70% of patients may ultimately develop bone erosions.1 Pain and swelling due to the inflammation, and later due to joint destruction, cause the patient limitation of movement and loss of functional abilities. The therapeutic approach of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) aims to suppress the inflammatory process in order to reduce pain and disability, and prevent future joint destruction. Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be of value in reducing pain and stiffness, but are ineffective in suppressing the disease itself. Antirheumatic drugs, known as ‘second-line’ (being introduced in the past only after failure of ‘firstline’ NSAIDs), ‘slow-acting’ (because of the period of 6 to 8 weeks or sometimes more before the effects of the drug become noticeable), or ‘disease modifying’ (hence abbreviated as DMARDs) attenuate the disease itself through a variety of mechanisms. Reductions in pain,2-7 swelling,2-9 acute phase reactants,3,7,9 and the progression of bony erosions10-15 have been demonstrated with these agents. Additionally, these agents are associated with improvements in functional status.4 However, the efficacy of these agents has been neither large in magnitude nor sustained in duration. Furthermore, side effects among these agents are common and may be severe or life threatening.16-20 Few patients continue individual second line agents for longer than 2 or 3 years perhaps as a result of the limited efficacy and toxic side effects of these agents.21-24 Based in large part on the recognition that joint destruction may occur within the first years of disease onset,1,25 the approach to therapy for rheumatoid arthritis has become more aggressive over recent years. Patients are being treated earlier and with more potent (and toxic) agents now than previously. It is thought that early intervention may prevent joint erosions and may prevent the disease from becoming self-sustaining.10 The few studies that have evaluated the efficacy of early intervention support this hypothesis.26-28 In one study, early introduction of DMARDs was more effective in suppressing disease activity than treatment with NSAIDs alone.28 In another study, early relative to later initiation of DMARDs resulted in improved functional status and attenuated radiographic progression that persisted for 5 years.27,28 The rationale behind using therapies including combinations of DMARDs with potentially greater toxicities in RA, centres around the premise that these agents will retard structural damage and prevent disability more effectively than less toxic agents. Although the efficacy of most single agents compared to placebo in the treatment of RA has been demonstrated,2-9 the relative efficacy of various DMARDs compared to other DMARDs and the relative efficacy of different combinations of DMARDs is less well understood. This no doubt stems in large part from the large number of different agents available to treat RA. Given that treatment regimens may include DMARDs (antimalarials, azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, gold, leflunomide, methotrexate, sulfasalazine), corticosteroids in higher or lower dosages and different 67 ways of administration, and biological agents (etanercept, infliximab), the number of possible combinations with two or more of these agents is quite large. The majority of these possible combinations have not been tested for effectiveness and safety. Some combinations that were tested in earlier years now appear to be farfetched or obsolete. This review is part of a study for the Dutch Health Care Insurance Council [College voor zorgverzekeringen (CVZ)], which has called for a study to develop a generic method for examining combinations of medications. The goal of this study is to develop a method that can be used to determine where clinical research on pharmaceutical combinations is needed by evaluating the existing published evidence and clinical expertise about the use of these combinations. This generic method is to be pilot-tested by addressing the problem of prioritising clinical research on combination medications for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Regarding rheumatoid arthritis specifically, the CVZ realises that there is much uncertainty regarding the relative efficacy of different combinations of DMARD therapy and would like to help resolve this uncertainty by financing clinical trials to assess the efficacy of combination therapy. In order to determine which DMARD combinations should be studied in these clinical trials, the CVZ would like to understand what has been published as well as the opinions of experts about the efficacy of combination DMARD therapy. This project will synthesise the existing published literature and expert opinion on this topic by using the RAND Appropriateness Methods (RAM). The RAM was originally developed over 15 years ago by a team of researchers at RAND and UCLA29,30 to assist in determining the extent of overuse of medical and surgical procedures (“inappropriate care”). The RAND Appropriateness Method (RAM) to determine "appropriate" care involves the following steps. When a topic has been selected, the first step of a study using the RAM is to perform a detailed literature review to synthesise the latest available scientific evidence on the procedure to be rated. The present document is the literature review for the appropriateness study on combination therapy with DMARDs. At the same time, a list of indications is produced in the form of a matrix that categorises patients who might present for the procedure in question in terms of their symptoms, past medical history and the results of relevant diagnostic tests. The literature review and the list of indications are sent to the members of an expert panel. These panel members individually rate the appropriateness of using the procedures for each indication on a nine-point scale, ranging from extremely inappropriate (=1) to extremely appropriate (=9) for the patient described in the indication. The panel members assess the benefit-risk ratio for the "typical patient with specific characteristics receiving care delivered by the typical surgeon in the typical hospital." After this first round of ratings, the panel members meet for one day under the leadership of a moderator. During this meeting, the panellists discuss their previous 68 ratings, focusing on areas of disagreement, and are given the opportunity to modify the original list of indications and/or definitions. After discussing each chapter of the list of indications, they re-rate each indication individually. The two-round process is focused on detecting consensus among the panel members. No attempt is made to force the panel to consensus. Previous uses of the RAM have concentrated on determining the appropriateness or inappropriateness of treatment.30,31 Here, we instead are using the method to reveal uncertain, but promising combinations. The following systematic review and summary of reviews on combination DMARD therapy in RA were performed as the first step of the RAM. 69 70 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF COMBINATION DMARD THERAPY IN RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS Identification of Clinical Trials We searched for clinical trials of combination therapy with DMARDs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis by using electronic searches of MEDLINE (1966- June 2000), EMBASE (1966 – June 2000) and the Cochrane Clinical Trials Registry (1965 – June 2000). The search terms used for each of these searches are described in table 1. Also, the bibliographies of major articles and reviews were screened for additional studies. Table 1. Search terms used for electronic databases. Database Search strategy Cochrane Clinical Trial Register “Arthritis, Rheumatoid” Embase “Combination therapy” and “Rheumatoid Arthritis” and names of single DMARDs Medline “Combination therapy” and “Rheumatoid Arthritis” and names of single DMARDs Inclusion Criteria We included only randomised clinical trials that reported the efficacy of combinations of two or more DMARDs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis among patients 18 years of age or older. For this review, corticosteroids administered on a daily basis were considered DMARDs. Only studies that included at least one of the following outcome measures were included in this review: tender and/or swollen joint count, pain, physician or patient global assessment, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or Creactive protein (CRP), radiographic outcome measures. Titles and abstracts for English and non-English language reports were reviewed to identify published studies. Articles in English, Dutch, German, French, Spanish and Danish were reviewed. Data Extraction Two trained reviewers collected qualitative data including the methodological attributes of the studies and characteristics of the study populations for each study using a standardised form. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The data abstraction forms for each study have been included in this review. Assessment of Methodological Attributes of Studies We assessed the methodological attributes of the studies by determining whether or not descriptions of the following were present in each study: randomisation, appropriateness of randomisation, blinding, appropriateness of blinding, withdrawals and dropouts, and concealment of allocation. Each of these items has been validated as an indicator of methodological quality either individually32-34 or as part of a scale.32,35,36 We assigned an overall quality score to each study using the method developed by Jadad.35 This method assigns points based upon the description of specific methodological parameters (see figure 1). Studies are assigned one point each for describing 71 randomisation, blinding, and withdrawals and dropouts. An additional point each is added for describing an appropriate method of randomisation and an appropriate method of blinding; one point each is deducted if studies describe inappropriate methods of randomisation and inappropriate methods of blinding. The maximum score possible is 5. Studies with scores of three or more on this scale are considered high quality32,37,38 and report systematically different treatment effects in some clinical settings than studies with lower scores.32,37,38 Figure 1. Assessing the Jadad-score Randomisation Was method of randomisation described? Yes: 1 point Blinding Was the study double blind? Yes: 1 point Was the method of randomisation appropriate? Yes: add 1 point No: subtract 1 point Was the method of blinding appropriate? Yes: add 1 point No: subtract 1 point Withdrawals and dropouts Was there a description of withdrawals and dropouts? Yes: 1 point Jadad score 72 Assessment of characteristics of study population Because baseline characteristics of study subjects may affect response to therapy, we abstracted data on the age, functional class, disease duration and prior use of DMARDs for all study arms in each study. Reviewers also qualitatively assessed whether meaningful differences in baseline characteristics of the study groups that could affect comparisons between arms were present in each study. RESULTS Trials Results from our literature search are detailed in figure 2. Figure 2. Literature retrieval flow chart. Citations from electronic search: CCTR: 1905 Medline: 259 Embase: 105 Total: 2269 Abstracts: CCTR: 66 Medline: 71 Embase: 61 Total: 198 Met inclusion criteria Check other reviews: 9 + Duplicates _ Selected articles (inclusion criteria + other reviews – duplicates): 64 Accepted 28 Rejected 35 (19 – no study 2 – language 5 – no RCT 9 – no combination therapy) Number of included studies: Total: 28 Our electronic search identified 2269 titles. Among these, 198 pertained to combination therapy with DMARDs for RA. The abstract for each selected title was reviewed and from these 64 articles were selected for review. Among these, 62 (97%) were retrieved and 24 met our inclusion criteria. The search of bibliographies of major articles and reviews resulted in eight more articles to be retrieved. Four of these eight met our inclusion criteria. Among the articles rejected, 17 did not describe a clinical trial, 73 but rather were letters, comments or reviews; 2 did not meet our language requirement (one article in Russian and one in Japanese); 5 were not randomised; and 8 articles were not about combination therapy as we defined it. The characteristics of the 28 studies included in this review are presented in table 2. Together, these studies assess the effects of 22 different combinations of DMARD therapies among 2819 patients. The majority (15) of the articles described studies on combinations with methotrexate, mostly combined with sulphasalazine, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine or cyclosporine. The number of patients varied from 24 to 211 and the number of treatment groups from 2 to 7. Quality scores The quality of the general methods of the studies assessed was generally good. The Jadad score was 3 or higher in 21 (79%) studies; concealment of allocation was described in 16 (57%) studies. Characteristics of study populations The average age of study participants ranged from 43.2 to 64. In most studies, the participants were aged 18-80. Disease duration ranged from 2.6 months to 11.5 years. Disease severity was described either in terms of functional class or the presence of rheumatoid factor in 8 and 12 studies respectively. Among studies that reported functional class, patients with Class I comprised 10% of the total subjects, Class II 73%, Class III 19% and Class IV 0.5%. Among studies reporting presence of rheumatoid factor, all reported that between 62 and 97% of the patients were rheumatoid factor positive. Whether or not DMARDs were used prior to study enrolment was described in 13 (46%) of the studies. In 11 studies, patients had been treated with DMARDs prior to study enrolment. In 18 studies, patients were randomly distributed over the different treatment arms, in 10 the procedure of allocation to treatment arms was less clear. In some cases there were some uncertainties about the comparability of the patients in the different arms (especially sex distribution and disease duration). In general, trials that compare newly started single drugs with newly started drug combinations offer a better insight than add-on studies, that compare the effect of adding another drug (or a placebo) to a drug that already failed. 74 Table 2. Characteristics of Eligible Clinical Trials of Combination DMARD therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis Combination First author, Year of publication Time of assessment (weeks) n patients (m/f) Disease duration (yrs) Disease severity % withdrawals Jadad score (1-5) Concealment of allocation CSA + CQ vs. CQ + plac. Borne van den, 199870 0, 12, 24 88 (25/63) RF: 68 vs 90% 25% vs 6% 5 Yes D-pen + CQ vs. CQ + plac. vs. D-pen + plac. D-pen. + MP vs. SSA + MP vs MP + plac. SSA + HCQ vs. SSA + plac. vs. HCQ + plac. SSA+ MP vs. SSA + plac. Gibson, 198734 8, 16, 24, 36, 48 72 (35/47) Not clear 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 45 (16/29) 2 Not clear 71 Faarvang, 1993 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 91 (35/56) RAI: 21 Vs. 20 Vs. 22 I: 71% II: 29% 5 Yes Ciconelli, 1996 8, 16, 24 38 (0/38) 6.9 vs. 6.1 23% vs. 5% vs. 7.6% 26.6% vs. 46.6% vs. 86.6% 26% vs. 41% vs. 29% 25% vs. 22% 1 Neumann, 198539 3.8 vs. 5.6 months 1 vs. 3 vs. 2 4 vs. 9 vs. 8 6.3 3-5 Yes Möttönen, 1999 12, 24, 36, 96 195 (74/121) 1 No O’Dell, 199640 7.3 vs. 8.6 months 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96 102 (31/71) 5 Yes ref.no SSA + MTX + HCQ + predn. vs. SSA + AUR SSA + MTX + HCQ vs. SSA + HCQ + plac. vs. MTX + plac.+ plac. SSA + MTX + HCQ vs. MTX + HCQ vs. MTX + SSA SSA+ MTX + predn. vs. SSA + plac. 72 73 24% vs. 22% 22.5% vs. 60% vs. 66.6% 131 O’Dell, 2000 (abstract) 74 Boers, 199710 10 vs. 6 vs. 10 II: 95% III: 5% vs. II:100% RF: 70% vs. 66% RF: 84% vs. 85% vs. 89% 16, 28, 40, 56 Yes 155 (64/91) Median: 4 vs. 4 months 75 RF: 78% vs. 72% 5 9% vs. 29% Yes Combination First author, Year of publication Time of assessment (weeks) n patients (m/f) SSA + MTX vs. MTX Haagsma, 199441 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 40 (8/32) SSA + MTX vs. MTX + plac. vs. SSA + plac. Dougados, 1999 0, 2, 4 the every 4 weeks until 52. 2,4, then every 4 weeks until 52 6, 12, 18, 24 205 (54/151) ref.no 75 Haagsma, 199742 MTX + AZA vs. AZA + plac. vs. MTX + plac. MTX + AUR vs. AUR + plac. vs. MTX + plac. Willkens, 199236 Disease duration (yrs) 105 (37/68) 209 (44/165) Disease severity RF: 77% vs. 72 % RF: 71% 62% 75% RF: 94% vs. 94% vs. 97% II: 84% vs. II: 80% vs. II: 78% 4.7 vs. 5.3 10.6 vs. 18.4 vs. 10.8 months 2.6 vs. 3.0 vs. 3.1 months Median: 8 vs. 8 vs. 10 Idem Idem Willkens, 199543 6, 12, 18, 24, 48 209 (44/165) Willkens, 199644 6, 12, 18, 24, 48 209 (44/165) Idem Idem Williams, 199245 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 335 (106/229) 6.2 vs. 4.6 vs. 5.3 Lopez-Mendez, 199346 48 200 3 vs. 2 vs. 3 (0-3): 2.0 vs. 1.85 vs. 1.94 III: 9 % III: 16 III: 20 76 % withdrawals Jadad score (1-5) Concealment of allocation 0 No 3/5 Yes 16.7% vs. 5% vs. 35% 5 Yes 26% vs. 38% vs. 75% 5 Not clear 45% vs. 64% vs. 33% 45% vs. 64% vs. 33% 37% vs. 40% vs. 34% 3-5 Not clear 3-5 Not clear 4 Not clear N.A. 4 Yes 9% vs. 0% 25% vs. 21.7% vs. 30.9% Combination First author, Year of publication Time of assessment (weeks) n patients (m/f) Disease duration (yrs) Disease severity % withdrawals Jadad score (1-5) Concealment of allocation MTX + CSA vs. MTX + plac. Tugwell, 199547 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 148 (41/107) 11.2 vs. 9.4 25% vs. 16% 5 Yes MTX + CQ vs. MTX + plc. Ferraz, 199448 8, 16, 24 68 (11/57) 9.24 vs. 6.19 21% vs. 21% 5 Yes MTX + IFX vs. MTX + plac. vs. IFX + plac. Maini, 199849 4, 8, 12, 16, 26 101 (73/28) 5 Yes MTX + cM-T412 Moreland, 199576 Trnavsky, 199350 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48 4, 12, 24 64 (22/42) II: 91% III 8% vs. II: 82% III: 15% II: 88% III:12% Vs. II: 79% III:21% RF: 72.2 vs. 76.0 vs. 90.8 II or III 3/4 Yes 4 Not clear Haar, 199351 6, 12, 18, 24 4 Yes ref.no HCQ + MTX vs. HCQ + plac. HCQ + DPS vs. HCQ + plac. vs. DPS + plac 12.6 vs. 10.6 vs. 7.6 8 vs. 10.9 40 (9/31) 80 (24/56) 77 Median: 0.98 vs. 3.0 vs. 1.02 II: 45% III: 55% vs. II: 50% III: 50% RF: 80% vs. 93% vs. 89% 7% vs. 57% vs. 27% NR 5% vs. 0% 56% vs. 17% vs. 17% Combination First author, Year of publication Time of assessment (weeks) n patients (m/f) Disease duration (yrs) Disease severity Bunch, 1984 77 24, 48, 72, 96 56 (17/39) 6.3 vs. 5.5 vs. 6.4 ARA*: II: 41% III: 59% Vs. II: 44% III: 44% Vs. II: 57% III: 38% (1-4) 2.86 vs. 2.62 RF: 80% vs. 85% RAI: 17 vs. 12 Seropos 73% vs. 71% RF: 79% vs. 81% ref.no HCQ + D-pen vs. HCQ + plac. vs. D-pen + plac. Corkill, 1990 78 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24 59 (21/38) 5.5 vs. 6.0 Van Gestel, 199552 12, 20, 44 40 (12/28) GST + HCQ vs. GST + plac Porter, 199353 26, 52 142 GST + HCQ vs. GST + plac. Scott, 198938 8, 16, 24, 36, 48 101 (31/70) 21.5 vs. 29.5 months Median: 6 vs. 5 2 vs. 2 GST + CSA Bendix, 199654 8, 16, 24 40 GST + MP vs. GST + plac. 10.7 vs. 11.5 * ARA scale for disease activity: I-II-III 78 % withdrawals Jadad score (1-5) Concealment of allocation 5 Yes 37% vs. 45% 3-5 Yes 65% vs. 45% 5 Yes 14.8% vs. 18.5% 3 Yes 48% vs. 35% 4 Not clear 15.7% vs. 5% 4 Yes 59% vs. 56% vs. 38% SUMMARY OF REVIEWS ON COMBINATION DMARD THERAPY During the literature search, reviews about combination therapy were retrieved as well, in order to get an oversight of existing systematic overviews. The most important reviews are summarised in table 3. 79 Table 3. Characteristics and Findings of Published Reviews on Combination DMARD Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis Review Years covered Search strategy and inclusion criteria Boers, 1991 1956 - 1989 • Borigini, 1995 1984 - 1994 Felson, 1994 ? - December 1992 Search in MEDLINE, Index Medicus, Excerpta Medica, and Science Citation Index, and search of bibliographies of retrieved articles • Randomised trials and cohort studies studies with evidence rated strong, moderate and weak are included • Concurrent therapy with at least 2 antirheumatic drugs, compared with one single drug • Outcome measure: severity of disease • Toxicity related to treatment is reported No description of search strategy and inclusion criteria • • • • • • • MEDLINE, bibliographic searches, hand searches of 5 international rheumatology journals, and abstracts of ACR-meetings Randomized clinical trials Patients > 18 years of age Two full-dose second-line drugs started concurrently Drugs and minimal dose: AUR (6 mg/day), HCQ (200 mg/day), CQ (250 mg/day), i.m. gold (50 mg/week), MTX (7.5 mg/week), AZA (1 mg/kg/day), SZA (2 mg/day), Dpen (500 mg/day) Numerical data on start and end values must be provided Comparison with one of the single secondline drugs listed above at full therapeutic 80 Number of studies 7 studies (in total: 427 patients) Conclusions Remarks The available trials provide insufficient data to decide with confidence that any combination of antirheumatic drugs is to be preferred over a single drug. Strict definition of active RA: 6 swollen joints plus 2 of 3 of the following criteria: - 9 or more tender joints - morning stiffness 45 minutes - ESR 28 mm/h 14 studies (in total: 1547 patients) 5 studies (in total 749 entering patients and 516 completing patients) Lack of well-designed, large, long-term, controlled clinical trials. Combination therapy does not offer a substantial improvement in efficacy, but does have higher toxicity than single drug therapy. Review Years covered dose Search strategy and inclusion criteria Verhoeven, 1998 1992 - 1997 • • • • Scott, 1999 1966 - 1990 • • MEDLINE search and search of bibliographies of the retrieved articles. English, French, German, Dutch Randomized studies - studies with evidence rated as strong or moderate are included Comparison with a one-type single DMARD control group MEDLINE search Randomised controlled trials, nonrandomised studies of parallel group design, observational open studies, retrospective reviews. 81 Number of studies 20 studies (10 on parallel treatment, 6 on step-up strategy, and 4 on stepdown strategy); in total 1952 patients 11 studies (in total: 486 patients) Conclusions In early RA patients, stepdown bridge therapy that includes corticosteroids leads to much enhanced efficacy at acceptable or low toxicity. The effects on joint damage may be persistent, but the symptomatic effects are probably dependent on continued corticosteroid dosing. In late patients, cyclosporine improves a suboptimal clinical response to methotrexate, and the triple combination of methotrexate, sulphasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine appears clinically better than the components. Other combinations are either untested, tested at low sample, or show negative interaction. The balance of evidence in 1990 suggested that combination therapy had a modest advantage. However, the trials were too small to detect its true value, and the combinations used were not ideal. Remarks Appendix A: Weighted mean differences between DMARD and placebo (95% confidence interval) for outcomes among patients with rheumatoid arthritis Outcome Tender Joint Count Drug Penicillamine -6.00 (<500 mg/d) (-11.36, 0.64) Penicillamine -6.61 (500 - 1000mg/d) (-11.37, 1.85) Penicillamine -8.90 (>1000 mg/d) (-16.63, 1.16) Sulphasalazine -2.448 (-4.15, 0.74) Methotrexate -17.85 (-23.97, 11.73) Cyclosporine -8.20 (-12.64, 3.76) Cyclophosphamide -9.62 (-17.72, 1.53) Swollen Joint Pain** Count -2.00 (-5.96, 1.96) -5.00 (-9.11, -0.89) . -2.379 (-3.73, -1.03) -7.31 (-10.44, 4.18) -3.19 (-4.29, -2.10) -6.88 (-12.04, 1.71) -11.00 (-23.19, 1.19) -0.63 (-1.00, 0.26) -0.61 (-0.91, 0.31) -8.71 (-14.80, 2.62) -3.00 (-4.07, 1.93) -1.45 (-2.32, 0.57) Physician Global Assessment -0.42 (-0.72, 0.12) -0.77 (-0.98, 0.56) -1.07 (-1.36, 0.78) -0.16 (-0.38, 0.01) Patient Global Assessment -0.36 (-0.65, 0.07) -0.56 (-0.86, 0.26) 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) -0.23 (-0.46, 0.00) -0.91 -1.05 (-1.20, (-1.31, 0.63) 0.80) 0.34 0.08 (-0.02, 0.69) (-0.25, 0.41) . . 82 . . Acute Phase reactant (ESR) -8.00 (-22.01, 6.01) . -10.65 (-20.89, -0.41) Functional Assessment * 13.90 (-37.03, 9.23) 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) -0.48 (-0.58, 0.38) -14.39 (-23.21, -5.58) -17.58 (-21.93, 13.23) -8.95 (-18.17, 0.27) . . . -11.61 (-25.72, 2.51) Azathioprine Antimalarials -3.08 (-5.24, 0.93) -2.57 (-3.78, 1.36) Injectable gold . -18.00 (-24.76, 11.24) -3.71 (-4.86, -2.57) -4.58 (-6.50, -2.65) -25.09 (-42.11, 8.07) -0.45 (-0.72, 0.18) . . -0.39 (-0.57, 0.21) -0.34 (-0.48, 0.20) *Functional assessment = Steinbrocker etc. **Pain = VAS 83 . -0.34 (-0.53, 0.15) -0.48 (-0.77, 0.19) -0.24 -12.94 (-0.79, 0.31) (-33.94, 8.05) -0.06 -6.38 (-0.29, 0.17) (-8.51, -4.24) . -13.16 (-18.14, -8.18) Appendix B. Adverse affects of selected disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Drug name Adverse effects % Citation 1-5 1-5 33 18-26 60-80 <1 1-3 <1 >10 2.5 1-2 6-10 <1 <5 <1 3-5 2.5-4.5 3-10 8 0-1.5 9.6-15.2 0-2.0 0-0.5 1.5-2.0 25-80 <2 <2 11 55 Hydroxychloroquine Retinal toxicity Sulphasalazine Gold (Auranofin) Methotrexate Azathioprine Cyclosporine Rash (and fever) Myelosuppression Gastrointestinal intolerance Rash Stomatitis Myelosuppression Thrombocytopenia Proteinuria Diarrhea Gastrointestinal intolerance Rash Stomatitis Alopecia Myelosuppression Hepatotoxicity Pneumonitis Leukopenia Hepatotoxicity Early flu-like illness with fever Anemia Nausea Thrombocytopenia Pancytopenia Alopecia Nephrotoxicity Anemia Thrombocytopenia Hypertension 84 55 56 56 57 58-60 57 61 62 63 64 64,65 65 63 66 63 67 56 67 67 67 67 67 67 56 56 56 56 Appendix B (continued). Adverse affects of selected disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Drug name Leflunomide Etanercept D-penicillamine Cyclophosphamide Infliximab Side effects % Transaminitis Gastrointestinal intolerance Teratogenicity (category x) Rash Alopecia Theoretic risk of infection Injection site reactions Upper respiratory symptoms Rash Stomatitis Dysgeusia Proteinuria Myelosuppression Secondary autoimmune disease Thrombocytopenia Myelosuppression Myeloproliferative disorders Infection Alopecia Hepatotoxicity Anaphylaxis Infection 85 Citation 6 15 56 8 1-7 56 56 56 56 37 Up to 45 Up to 50 >10 >10 <1 <1 <1 5 56 40-60 56 56 56 68 68 68 68 68 69 References 1. Van Der Heijde D. Joint erosions and patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheum. 1995;34:74-78. 2. Suarez-Almazor M, Spooner C , and Belseck E. Penicillamine for rheumatoid arthritis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library. 1999;4:Update Software. 3. Suarez-Almazor M, Belseck E, Shea B, Wells G , and Tugwell P. Sulfasalazine for rheumatoid arthritis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library. 1999;4:Update Software. 4. Suarez-Almazor M, Belseck E, Shea B, Wells G , and Tugwell P. Methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library. 1999;4:Update Software. 5. Wells G, Haguenauer D, Shea B et al. Cyclosporine for rheumatoid arthritis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library. 1999;4:Update Software. 6. Suarez-Almazor M, Spooner C , and Belseck E. Azathioprine for rheumatoid arthritis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library. 1999;4:Update Software. 7. Suarez-Almazor M, Belseck E, Shea B, Homik J , and Wells GTP. Antimalarials for rheumatoid arthritis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library. 1994;4:Update Software. 8. Suarez-Almazor M, Belseck E, Shea B, Wells G , and Tugwell P. Cyclophosphamide for rheumatoid arthritis (Cochrane Review). In: The 86 Cochrane Library. 1999;4:Update Software. 9. Clark P, Tugwell P, Bennet K et al. Injectable gold for rhuematoid arthritis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library. 1999;4:Update Software. 10. Boers M, Verhoeven A, Markusse H et al. Randomised comparison of combined step-down prednisolone, methotrexate and sulphasalazine with sulphasalazine alone in early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1997;350:309-318. 11. Bresnihan B, Alvaro-Garcia J, Cobby M et al. Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis with recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor anatagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:2196-2204. 12. Forre O, and the Norwegian Arthritis Study Group. Radiologic evidence of disease modification in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with cyclosporine. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1506-1512. 13. Kirwan J, and The arthritis and rheumatism council, low-dose glucocorticoid study group. The effect of glucocorticoids on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis . N Engl J Med. 1995;333:142-146. 14. Smolen J, Kalden J, Scott D et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide compared with placebo and sulphasalazine in active rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 1999;353:259-266. 15. Strand V, Cohen S, Schiff M et al. Treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with Leflunomide compared with placebo and Methotrexate. Arch Intern Med. 87 1999;159:2542-2550. 16. Lockie L, and Smith D. Forty-seven years experience with gold therapy in 1019 RA patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1985;14:238-246. 17. Gerber R, and Paulus H. Gold therapy . Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1975;1:307318. 18. Weinblatt M. Toxicity of low dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheum. 1985;12:35-39. 19. Singh G, Fries J, Spitz P , and Williams C. Toxic effects of azathioprine in RA: a national post-marketing perspective. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:837-843. 20. Cash J, and Klippel J. Second line drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1368-1375. 21. Pincus T, and Callahan L. The "side effects" of rheumatoid arthritis: Joint destruction, disability and early mortality. Br J Rheum. 1993;32:28-37. 22. Pincus T, Marcum S , and Callahan L. Longterm drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis in seven rheumatology private practices: II Second line drugs and prednisone. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1885-94. 23. Pincus T, The case for early intervention in rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun. 1992;5:209-226. 24. Wolfe F, Hawley D , and Cathey M. Termination of slow acting antirheumatic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a 14-year prospective evaluation of 1017 88 consecutive starts. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:994-1002. 25. Van der Heijde D, Van Leeuwen M, Van Riel P et al. Biannual radiographic assessments of hands and feet in a three year prospective follow-up of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35: 26. Van der Heijde A, Jacobs J, Bijlsma J et al. The effectiveness of early treatment with ‘second-line’ antirheumatic drugs. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124: 27. Egmose C et al. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis benefit from early second line therapy: 5 year follow-up of a prospective double blind placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:2208-2213. 28. Borg G, Allander E, Lund B et al. Auranofin improves outcome in early rheumatoid arthritis. Results from a 2-year double blind, placebo controlled study. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1747-1754. 29. Park R, Fink A, Brook R et al. Physician ratings of appropriate indications for six medical and surgical procedures. Am J Pub Health. 1986;76:766-772. 30. Brook R. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method . Methodology Perspectives . 1994;Rockville, Maryland: Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, AHCPR Publication No. 95-0009, pp. 59-70. 31. Fitch K, Bernstein S, Aguilar M et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. User’s Manual. Santa Monica;2000: MR-1269. 89 32. Moher D, Pham B, Jones A et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998;352:609-613. 33. Schulz K, Chalmers I, Hayes R et al. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408-412. 34. Gibson T, Emery P, Armstrong A, Crisp A , and Panayi G. Combined dpenicillamine and chloroquine treatment of rheumatoid arthritis - a comparative study . Br J Rheum. 1987;26:279-284. 35. Jadad A, Moore A, Carrol D et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. 36. Willkens R, Urowitz M, Stablein D et al. Comparison of azathioprine, methotrexate, and the combination of both in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: A controlled clinical trial. A&R. 1992;35:849-856. 37. Kahn K, Daya S , and Jadad A. The importance of quality of primary studies in producing unbiased systematic reviews. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:661-666. 38. Scott D, Dawes P, Tunn E et al. Combination therapy with gold and hydroxychloroquine in rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective, randomized, placebocontrolled study. Br J Rheum. 1989;28:128-133. 39. Neumann V, Hopkins R, Dixon J et al. Combination therapy with pulsed 90 methylprednisolone in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44:747-751. 40. O'Dell J, Haire C, Erikson N et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate alone, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or a combination of all three medications. NEJM. 1996;334:1287-1291. 41. Haagsma C, Van Riel C, De Rooij D et al. Combination of methotrexate and sulphasalazine vs methotrexate alone: a randomized open clinical trial in rheumatoid arthritis pateints resistant to sulphasalazine therapy. Br J Rheum. 1994;33:1049-1055. 42. Haagsma C, Van Riel P, De Jong A , and Van de Putte L. Combination of sulphasalazine and methotrexate versus the single components in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled, double-blind, 52 week clinical trial. Br J Rheum. 1997;36:1082-1088. 43. Willkens R, Sharp J, Stablein D, Marks C , and Wortmann R. Comparison of azithioprine, methotrexate, and the combination of the two in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a forty-eight-week controlled clinical trial with radiologic outcome assessment. A&R. 1995;38:1799-1806. 44. Willkens R, and Stablein D. Combination treatment of rheumatoid arthritis using azathioprine and methotrexate: a 48 week controlled clinical trial . J Rheum. 1996;23:64-68. 45. Williams H, Ward J, Reading J et al. Comparison of auranofin, methotrexate, and the combination of both in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a controlled 91 clinical trial. A&R. 1992;35:259-269. 46. Lopez-Mendez A, Daniel W, Reading J, Ward J , and Alarcon G. Radiographic assessment of disease progression in rheumatoid arthritis patients enrolled in the cooperative systematic studies of the rheumatic diseases program randomized clinical trial of methotrexate, auranofin, or a combination of the two. A&R. 1993;36:1364-1369. 47. Tugwell P, Pincus T, Yocum D et al. Combination therapy with cyclosporine and methotrexate in severe rheumatoid arthritis. NEJM. 1995;333:138-141. 48. Ferraz M, Pinheiro GHM, Albuquerque E et al. Combination therapy with methotrexate and chloroquine in rheumatoid arthritis: A multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994;23:231-236. 49. Maini R, Breedveld F, Kalden J et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. A&R. 1998;41:1552-1563. 50. Trnavsky K, Gatterova J, Linduskova M , and Peliskova Z. Combination therapy with hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Zeit fur Rheum. 1993;52:292-296. 51. Haar D, Solvkajaer M, Unger B et al. A double-blind comparative study of hydroxychloroquine and dapsone, alone and in combination, in rheumatoid arthritis. 1993;22:113-118. 92 52. Van Gestel A, Laan R, Haagsma C, Van De Putte L , and Van Riel P. Oral steroids as bridge therapy in rheumatoid arthritis patients starting with parenteral gold. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Br J Rheum. 1995;34:347-351. 53. Porter D, Capell H , and Hunter J. Combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis no benefit of addition of hydroxychloroquine to patients with a suboptimal response to intramuscular gold therapy. J Rheum. 1993;20:645-9. 54. Bendix G and Bjelle A. Adding low-dose cyclosporin a to parenteral gold therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Br J Rheum. 1996;35:1142-1149. 55. Day R. Sulfasalazine . Textbook of Rheumatology. 1993;4th Ed.:Philadelphia, WB Saunders. 56. Micromedex Inc. Micromedex Healthcare Series. 2000. 57. Gordon D. Gold compounds in the rheumatic diseases. in textbook of rheumatology 4th ed. 1993;Philadelphia, WB Saunders. 58. Lockie L and Smith D. Forty-seven years experience with gold therapy in 1019 RA patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1985;14:238-246. 59. Davis P and Hughes G. Significance of eosinophilia during gold therapy. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1974;17:964-968. 60. Gerber R and Paulus H. Gold therapy . Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1975;1:307- 93 318. 61. Kelley, W, Harris, E, Ruddy, S, and Sledge, C. Volume 1. Textbook of Rheumatology. 5th edition Philadelphia, PA; W.B. Saunders Company. 97 (Ch. 48). 62. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Clinical Guidelines. Guidelines for monitoring drug therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1996;39:723-731. 63. Weinblatt M. Methotrexate, in textbook of rheumatology. 4th ed. 1993;Kelley WN, Harris ED Jr., Ruddy S, Sledge CB eds. 64. Klippel, J and Dieppe, P. Rheumatology. London; Times Mirror International Publishers Limited. 94 (8.13.3). 65. Weinblatt M. Toxicity of low dose methotrexate in RA. J Rheum. 1985;12:35-39. 66. Kelley, W, Harris, E, Ruddy, S, and Sledge, C. Volume 1. Textbook of Rheumatology. 5th edition Philadelphia, PA; W.B. Saunders Company. 97 (Ch. 49). 67. Singh G, Fries J, Spitz P, and Williams C. Toxic effects of azathioprine in RA: a national post-marketing perspective. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1989;32:837-843. 68. Jaffe I. Penicillamine . in textbook of rheumatology 4th ed. 1993. 69. Cash J and Klippel J. Second line drug therapy for RA. New England J of Med. 1994;330:1368-1375. 94 70. Van den Borne, B.E.E.M., R.B.M. Landewé, et al. Combination therapy in recent onset rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized double blind trial of the addition of low dose cyclosporine to patients treated with low dose chloroquine. J Rheumatol 1998; 25:14938. 71. Faarvang K.L, Egsmose C. et al. Hydroxychloroquine and sulphasalazine alone and in combination in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised double blind trial. Ann Rheum Dis 1993; 52:711-715. 72. Ciconelli R.M., Ferraz M.B, Visioni R.A., Oliveira L.M. and E. Atra. A randomized double-blind controlled trial of sulphasalazine combined with pulses of methylprednisolone or placebo in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Br.J. of Rheum. 1996; 35: 150-154. 73. Möttönen T, Hannonen P. et al. Comparison of combination therapy with single-drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Lancet 1999; 353: 1568-1572. 74. O’Dell J, Lelf R, et al. Methotrexate (M)- Hydroxychloroquine (H)- Sulfasalazine (S) versus M-H of M-S for rheumatoid arthritis (RA): results of a double blind study. 2000. Abstract submitted for ACR conference November 14, 1999. 75. Dougados M, Combe B et al. Combination therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, controlled, double blind 52 week clinical trial of sulphasalazine and methotrexate compared with the single components. Ann Rheum Dis 1999; 58: 220-225. 76. Moreland L.W, Pratt, P.W, et.al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial using chimeric monoclonal anti-CD4 antibody, cM-T412, in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate. Arthritis & Rheumatism 1995; 38 vol 11: 15811588. 95 77. Bunch Th.W, O’Duffy J.D., Tompkins R.B, and W.M. O’Fallon. Controlled trial of hydroxychloroquine and D-penicillamine singly and in combination in the treatment of rheuamtoid arthritis. Arthritis & rheumatism 1984; 27: 267-276. 78. Corkill M.M, B.W. kirkham, I.C. Chikanza, T. Gibson and G.S. Panayi. Intramuscular depot methylprednisolone induction of chrysotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a 24-week randomized controlled trial. Br.J. of Rheum 1990; 29: 274-279. 96 Data abstraction tables In the following part of the literature review, you will find that some pages have been left blank. This has been done on purpose, as some tables are read more easily if the pages face eachother. 97