Processing The Crime Scene 3

advertisement

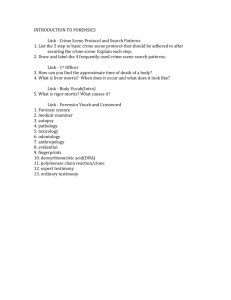

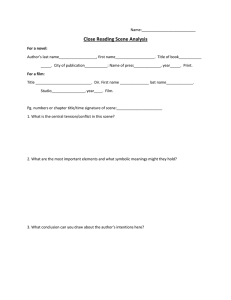

3 Processing The Crime Scene 3.1 Introduction The term “processing the crime scene” refers to the sequence of events by which all evidence at a scene is located, recorded and collected. It can be a lengthy process. EXERCISE 3.1 What are some factors that determine the time taken to process a scene? The steps involved in processing the scene are: 1. Initial photography – this establishes the appearance of the scene and is often done during the preliminary survey 2a. Sketching the crime scene – this is done by hand in the field, but will include measurements of dimensions and distances; a more accurate and neater version can be constructed later back at a computer 2b. Searching the scene to locate the evidence – this has to be done carefully and systematically to ensure that all evidence is found 2c. Documenting the location of the items of evidence in writing and by photography – before the evidence is collected and removed from the scene, its presence at the scene must be proven 3. Collecting the evidence – different types of evidence require different methods of collection, storage and handling to avoid them being damaged or contaminated before analysis Steps 1 & 3 are done in the order shown, while steps 2a‐c are not done separately, but will interlink with each other. 3.2 Sketching the crime scene A crime scene is not a landscape painting or an architectural plan: it is a hand‐drawn representation of the basic layout of the important aspects of the scene. EXERCISE 3.2 What are the important aspects of the scene that should be recorded on the sketch? 3. Processing the crime scene Not everything will appear on the sketch at the same time. The starting point will be the basic layout, including the fixed items which are not pieces of evidence, but simply part of the scene. For indoor scenes, this will include doors, windows, walls and furniture while for external scenes, it will include buildings, roads, trees and creeks. Accurate measurements of the dimensions of the scene need to be made so that items of evidence can be located exactly on the sketch. The sketch doesn’t have to be perfectly to scale, as long as measurements indicate distances etc. The bird’s eye view (i.e. from above) – the ground/floorplan – is the usual means of sketching the scene, but important evidence is found in an elevated position above the floor/ground, a second sketch will be required to show its location. This will be usually a diagram known as an elevation, which is simply a vertical plane, rather than the horizontal floorplan. After the layout is complete, the location of pieces of evidence that are immediately obvious (eg a body) can be placed on the sketch. For small items, this will be done by a code letter, with an explanatory legend below. For larger items they can be drawn in and labelled. Location of all items in the sketch should be located by accurate measurements from two directions, as shown in Figure 3.5. This is known as triangulation, because you are essentially drawing a triangle with the object of interest being one point in the triangle. Inside, this can be the distance of the object from two walls, while outside, two fixed points (road, telegraph pole, building) will be needed to locate the item. 1200 Scale: mm A A: shotgun cartridge 875 FIGURE 3.1 Locating an item by triangulation If the case is sufficiently important, the rough hand‐drawn sketch drawn at the scene can be converted into a accurately scaled, tidy version by a computer drawing specialist, but the hand‐ drawn version remains critical in terms of continuity of evidence. Figure 3.2(a) & (b) shows a rough sketch from the scene and its “tidied up” version, while Figure 3.3 is a real crime scene sketch from an unsolved case of the 1950s (“The Boy in the Box”). EXERCISE 3.3 For the sketches in Figures 3.2(a) & 3.3, identify which components would have been added first. Crime Scene Processing 3.2 3. Processing the crime scene FIGURE 3.2(a) Rough sketch of a mock crime scene (from Saferstein, Criminalistics) Crime Scene Processing 3.3 3. Processing the crime scene FIGURE 3.2(b) Tidy sketch of a mock crime scene (from Saferstein, Criminalistics) Crime Scene Processing 3.4 3. Processing the crime scene FIGURE 3.3 Actual crime scene sketch (from http://americasunknownchild.net/default.htm) Crime Scene Processing 3.5 3. Processing the crime scene 3.3 Searching Not all pieces of evidence are as obvious as a bleeding corpse, a smoking gun or a bloodied fingerprint. Some items of evidence may be hidden, or very small or invisible. Some are not really physical items at all in that they can’t be put in a bag, but rather observations about the scene itself. EXERCISE 3.4 Give examples of physical evidence that is: (a) hidden (b) very small (c) invisible Give examples of non‐physical evidence that can be observed during the search of a crime scene? It may also be spread over a large area. Think of the search for evidence associated with the Ivan Milat case, all those people spending all that time painstakingly working their way through hectare after hectare in the Belanglo Forest or the search for pieces of the aeroplane blown up over Lockerbie (Scotland). A crime scene search requires three qualities: attention patience system EXERCISE 3.5 Why are these qualities important? Attention Patience System Crime Scene Processing 3.6 3. Processing the crime scene Attention and patience are obviously personal traits that the searcher needs to possess, but a system is a matter of following a procedure. Figure 3.4 shows a number of possible search patterns which provide a systematic means of searching a crime scene. FIGURE 3.4 Search patterns The grid and strip/line searches work best on large areas, while the quadrant/zone search can be used to make a area more manageable for individual searching (this could be a room or outside). The spiral search can only work in small areas, and would be best done from an obvious starting point such as a body. There is no one right way to do a particular search, and experience will provide the best guide. This is where the search coordinator comes in: experience from a wide range of crime scenes will guide his/her decision. Where there are more one person involved in the search (and time allows), areas may be searched twice by different people to maximise the chances of finding everything. The hardest part of a crime scene is recognising what is evidence and what is just stuff. This is partly a matter of common sense, and partly down to experience. A cigarette butt found in bushes near the crime may be very important, or it may be one thrown down by a passerby the day before the crime or six months earlier. Some items will show their age by weathering and can be discarded. An excellent article about this topic is “Searching and Examining a Major Crime Scene” by HW Ruslander1. It lists a number of things to look for that aren’t necessarily items or trace evidence, but rather observations about the state of the scene and the objects within it and how that helps to identify what is evidence and what is simply an object at the scene with no useful connection to the crime. This list is reproduced in its entirety below. 1 http://www.crime‐scene‐investigator.net/searchingandexamining.html Crime Scene Processing 3.7 3. Processing the crime scene Doors, are they locked or bolted (from the inside or outside), are there marks of forced entry, does the doorbell work, is there a doorknocker, are there scratches around the keyhole, etc. Windows, what type, are they locked or unlocked, open or broken, note the type and position of curtains, drapes or blinds. Newspapers and mail, is the mail unopened or read or not, check the postmarks on envelopes and the dates of newspapers. Lights, which ones were on when the crime was discovered, how are they controlled, by timers, motion sensors or switches. Can they be seen from the outside. Are the bulbs broken or unscrewed? Smells, do you or did the first responding officer notice the smell of gas, tobacco, alcohol, perfume, gun powder or anything else unusual. Kitchens, was food being prepared, if so, what kind (it may or may not correspond with the victims stomach contents). Is there food that was partially eaten, utensils, glasses or plates. Is the stove warm or still on, Are there signs of attempts to burn or wash away evidence. Are there signs of clean up attempts. Heating/Air Conditioners, what type is it, is it vented or unvented (carbon monoxide can kill). What is the thermostat setting. Are there signs of a party, such as empty bottles (note the labels, brands, types of liquor, etc.) are there cups, glasses and what is their contents, how many are there, is lipstick on any of them, how many places are set at the table. Note contents of ashtrays, cigarette packs and butts, brands, the way in which the cigarettes were extinguished, is there tooth marks or lipstick on them. Remember, DNA is easily obtained from the butts, preserve them properly. Contents of waste baskets and trash cans, has anyone been going through them looking for anything, is the trash in proper order (dates on newspapers, letters, etc.). Clocks and watches, are they wind‐up or electric. Are they running, do they show the right time, what time are alarm clocks set for. Check timers on VCR's, microwave ovens, etc. Bathrooms and vanities, are towels, rags etc. damp to touch or dry. Are they bloodstained. Check for signs that the suspect cleaned up afterwards or was injured and bled at the scene. Is the toilet seat and lid left up? In a woman’s house, this could be a piece of important information. Check medicine cabinets for drugs, check the tanks of toilets, that is a great place to hide things. General disorder, is there evidence of a struggle, is the place just dirty, etc. Shootings, how many bullets were fired, account for all of them if possible, find cartridge cases (number and location found) if there are any bullet holes (number and location), was the weapon left at the scene. There may be expended cartridge casings found laying on the floor, rug or on furniture. It is recommended to mark these items, after photographing them first, with numbered markers to prevent their being moved, altered or damaged. If necessary, they may be protected by placing water glasses over them. Stabbing and beatings, was the instrument left at the scene, could it have come from that location or was it brought to the scene by the suspect. Crime Scene Processing 3.8 3. Processing the crime scene Blood, document the location, degree of coagulation, type (spots, stains, spatters, pooling, etc.). Sketch and photograph the bloodstains. Remember, when a body fluid begins to decompose, it will discharge a reddish brown fluid which resembles blood, when describing this, be objective, call it what it is, a reddish brown fluid. Bloodspatter analysis may be used to reconstruct violent crimes. Carefully photograph all blood patterns using scales. DO NOT cover up patterns with the scales if possible. Remember, always look up, cast‐off spatter will probably be on the ceiling. Hangings and strangulation, what instrument or means was used, was it obtained in the house or brought to the scene, are there any portions remaining. If a suspected auto‐erotic death, look for signs of prior activities such as rope marks on door frames or rafters. Be prepared for scene re‐arranging by ashamed family members. Remember, do not cut the victim down if he/she is obviously dead until all aspects of the investigation have been covered. Never cut through the knot and always use a piece of string tied to each end of the cut to re‐connect the circle. Look at stairs, hallways, entries and exits to the scene, check for footprints, debris, discarded items and fingerprints. Attempt to determine the route used to enter and exit the scene by the suspect and avoid contaminating it. Presence of items that do not belong there, many suspects, in the heat of the moment, will leave items of great evidential value, don't overlook this possibility. Is there signs of ransacking, to what degree, if any, has the scene been ransacked. Was anything taken (relatives and friends can assist in making this determination). Look for hiding places for weapons which the suspect may have had to conceal quickly, check behind stoves, on top of tall furniture, behind books, among bedclothes, under the mattress, on the roof. There are two other absolutely crucial elements of a search – it should not: disturb evidence before it is recorded, and contaminate or destroy evidence Numbered markers are put down near the evidence, to clearly indicate its presence, and to help identify that evidence in the documentation (photographic and written). For example, if there were five cartridge casings at the scene of a multiple shooting, a close‐up photo of one casing would not be very helpful, unless it had a numbered marker next to it. Each piece of evidence is then recorded on a Evidence Log, which notes (part from the overall scene details): tag number item description person who found it (if more than one involved in the search) other information 3.3 Documenting Recording the processing of the crime scene uses a range of methods: the “good old” hand‐written notes (and the new‐fangled laptop equivalent, though a laptop around a crime scene is not really feasible for searching, so it is more likely to stay in a central point and be used as a collating tool) still photographs video Crime Scene Processing 3.9 3. Processing the crime scene Each method has its advantages and disadvantages, and essentially complement each other. Even the lowest level crime scene can be documented by written notes in a police officer’s notebook, while more significant scenes with crime scene officers in attendance will have still and video imaging. EXERCISE 3.6 What extra value in documenting the processing of the crime scene is provided by: (a) still photographs (b) video (c) written notes Written notes Notes made at the crime scene will only be brief dot‐point lists, as you don’t have time to be writing beautiful essays. Noting the sequence of events is as important as recording your observations. The essential aspects of note‐taking at a crime scene are: made at the time that events occur, not afterwards made in chronological order detail all actions complete and thorough clearly and legibly written record unexpected or negative conditions (e.g. lack of blood around victim, no signs of forced entry, lights on/off) be specific record the relevant leave fine detail to photography Photography It is not possible to cover all the aspects of photography (still and video) as applied to forensic work, so we will deal only with the basics of documenting the scene and recording evidence at a simple simulated crime scene. Trained forensic photographers are able to deal with the difficult conditions that are found at night, in the morgue etc and to recognise features of arson scenes that need to be documented. Crime Scene Processing 3.10 3. Processing the crime scene Still photography Photographs taken at a crime scene are of three basic types: overall – these provide a basic overview of the layout of the scene evidence‐establishing – these demonstrate the location of items of evidence relative to the recognisable parts of the scene (eg walls, furniture, trees, cars) evidence‐closeup ‐ record the presence and appearance of the physical evidence OVERALL PHOTOS These photos are generally taken from the perimeter of the scene. It is very unlikely that one single wide angle photo will be able to cover the entire scene, even if it is a small room. EXERCISE 3.7 Why can’t one overall photo cover even a small room? Therefore, there will be a need to take a number of these shots to fully show the layout. The best approach is to take one from each “corner” of the scene, and if it is very large, then from the middle of each “side”. Essentially what you looking for is coverage of the whole area in a way that clearly shows the main features. ESTABLISHING Overall photographs may show some of the larger evidence items, but not all, and certainly not in enough detail for useful recognition. To ensure that the location of all items of evidence are shown in these mid‐range photographs, numbered labels are employed. These can also have size scales incorporated which allows the dimensions to be shown in the closeup photos. These will also help if there are multiple of the same type of item (eg bullet casings) since the documenting of the evidence become much easier and reduces the chance of error. FIGURE 3.5 Establishing photograph of a bullet hole and bloodstain (Crime Scene Processing & Investigation, Gardner) Crime Scene Processing 3.11 3. Processing the crime scene CLOSEUPS These show clearly the detail of the evidence or even parts of the evidence, eg a wound on a body. The major mistake in closeup photos is to not fill the frame with the item. However, it must clear what is being photographed, so its numbered label must also be in shot. In most cases, a ruler scale alongside the item ensures there can be arguments about its size later on. There have been some instances of defense lawyers arguing that the presence of the label and/or scale affects the picture, so it is recommended by some experts that two photographs be taken: with and without the label. EXERCISE 3.8 How would you take the closeup photo for the evidence in Figure 3.5 so that the scale is evident? EXERCISE 3.9 Assume you are required to photograph a house that has been burgled. What photographs of each type should you take? Overall Establishing Closeup Videography You may see little role for video evidence at a crime scene, but video is becoming increasingly necessary for thorough documentation of the full crime scene. Video can provide the jury (and all those in the courtroom) with a guided tour of the entire crime scene – showing how each part links to the other – potentially showing how things were at the time of occurrence of the crime. This can be done repeatedly if required by the judge or jury – which allows for through checking of detail at the scene. It would be difficult to provide such a service using any other medium. Video recording is necessary as it is often not possible to transport all of the trial participants to the crime scene for first hand viewing. It will not replace sketches or still photography, but rather should be used to complement them – with each seen as an important part of providing the whole story. There are 2 key uses for video evidence: to document the entire scene, and to prove that an event occurred. In the case of the latter you may think that it sounds funny, but a video of a blazing building burning down is unequivocal evidence that the fire took place and that the building was not destroyed in a bomb blast or had been previously knocked down and partially burnt. Additional reasons for using video might include documentation of: the extent of damage, materials not damaged showing the presence of physical evidence at the scene (and its location relative to other items of evidence) showing the presence of individuals at the scene. Crime Scene Processing 3.12 3. Processing the crime scene In the case of the latter it is security cameras that provide the greatest amount of evidence, however occasionally a forensic photographer or videographer will be required to document the presence of an individual at the crime scene. There are two types of video taping that are used for evidence presentation: evidential and non‐evidential. The former is used in a trial and presented directly as evidence. The latter may be taken to help investigators, but is not used in court. Non‐evidential material can be recorded like any other home video, with no real precautions and with full sound. When recording video for evidence presentation – special techniques MUST be followed. EVIDENTIAL VIDEO RECORDING You have all probably heard the expression “anything that you say may be held against you”. In the case of forensic evidence gathering by video, it certainly holds very true. Anything that you record – both audio and visual are admissible as evidence, and open for critical examination – especially by the opposition. Hence any inappropriate comments uttered during the evidence gathering process are likely to be detrimental to the case. For this reason it is normal practice that no sound will be recorded on a crime scene video. There are some exceptions to this rule such as when a personal interview may be recorded at the crime scene – but these are fairly rare. Original videotape or memory cards must be retained. A high quality second generation copy of the original may be used in court room evidence, but the original MUST be available if required. It is important that the material presented in court is high quality, as poor copies can be deemed inadmissible. It is for this reason that high quality digital cameras should always be used. Any copying of the original evidential tape should be documented, and the original stored safely in a non‐erasable form away from heat, moisture and magnetic fields. Back‐up copies should be made as soon as possible after recording the original. TIPS FOR RECORDING EVIDENTIAL MATERIAL When recording evidence with a video camera keep the following things in mind: You are there to provide an unbiased record of facts, conditions and the sequence of events for a crime scene There may be visual requirement to prove that a crime actually occurred Your role is to bring the crime scene into the courtroom – and to allow the facts to be displayed multiple times if necessary Record most of your video at eye level, unless there is a special need and evidence cannot be gathered any other way. Record in the highest quality format/picture that you possibly can (HDV or better is desirable) Try to use supports such as tripods where ever possible to avoid shaky video that will look unprofessional in court and may bias your case Pre‐plan your shooting sequence before you record, as the great majority of evidence gathering will involve in‐camera editing. Note: In Western Australia evidence must be gathered in one take – so you cannot switch the camera on and off. In all other states in‐camera edits are allowed, but timecode must be continuous. Try and operate your camera with both eyes open, using one eye to watch the recording in the viewfinder and the other to watch the scene to avoid accidents such as trips Video all parts of the crime scene in the same fashion using the same techniques (to avoid it looking like you are biasing certain parts of the evidence) Make sure that the time, date and timecode are recorded to tape in a continuous fashion. You can do this by “black striping” the tape if necessary. This involves recording the entire tape with the cap on (or colour bars), then rewinding and recording over it. NEVER record sound unless there is a specific need Obviously you cannot re‐use evidential tape Follow the tips for shooting as described in the video primer in the first section of these notes. Ensure that lighting of the crime scene is appropriate so that the evidence is clearly visible. It may be necessary to use additional lighting as required. Crime Scene Processing 3.13 3. Processing the crime scene When shooting a sequence for evidence collection, it is not a bad idea to record the establishing shot, then spectators and emergency services personnel at the scene first as these may leave at any time. If you are recording vehicles – circle the whole vehicle to make sure that you document all damage to the vehicle. When entering burnt out structures, always record from the least burnt to the most burnt section – with the latter being the likely source (origin) of the fire. You should also always work with police and emergency services to record any evidence or material that they require. POST RECORDING There are some critical steps that MUST be taken upon completion of evidence gathering. You should always remember to: Engage the erasure prevention tab of the tape/memory immediately Check your recording by playing it back to ensure that it has been recorded successfully Label the recording carefully in indelible ink – including the date, time location and any important notes Copy the recording as soon as possible Store the recording in a safe place Strictly maintain all chain of custody requirements/protocols One last point is to make sure that all your recording equipment and tapes/memory is ready to go at very short notice – you never know when you will be required to gather evidence. 3.4 Collection and Preservation of Evidence2 Once the crime scene has been thoroughly documented and the locations of the evidence noted, then the collection process can begin. This will usually start with the collection of the most fragile or most easily lost evidence. Special consideration can also be given to any evidence or objects which need to be moved. EXERCISE 3.10 (a) What types of evidence are the most fragile/easily lost? (b) What types of evidence might need to be moved? Collection can then continue along the crime scene trail or in some other logical manner. Photographs should also continue to be taken if the investigator is revealing layers of evidence which were not previously documented because they were hidden from sight. Each type of evidence has a specific value in an investigation. The value of evidence should be kept in mind by the investigator when doing a crime scene investigation. For example, when investigating a crime, more time should be spent on collecting good fingerprints than trying to find fibres left by a suspect's clothing. 2 These notes on collection & packaging of evidence are adapted from the article by George Schiro at http://www.crime‐scene‐ investigator.net/evidenc3.html. Crime Scene Processing 3.14 3. Processing the crime scene General rules for packaging evidence most items of evidence will be collected in paper containers such as packets, envelopes, and bags. liquid items can be transported in non‐breakable, leakproof containers. arson evidence is usually collected in air‐tight, clean metal cans. only large quantities of dry powder should be collected and stored in plastic bags. moist or wet evidence (blood, plants, etc.) from a crime scene can be collected in plastic containers at the scene and transported back to an evidence receiving area if the storage time in plastic is two hours or less and this is done to prevent contamination of other evidence once in a secure location, wet evidence, whether packaged in plastic or paper, must be removed and allowed to completely air dry; that evidence can then be repackaged in a new, dry paper container; under no circumstances should evidence containing moisture be packaged in plastic or paper containers for more than two hours; this would allow the growth of micro‐organisms which can destroy or alter evidence any items which may cross contaminate each other must be packaged separately the “containers” should be closed and secured to prevent the mixture of evidence during transportation each “container” should have: ‐ a unique identifying code number ‐ the collecting person's initials ‐ the date and time it was collected ‐ a description of the contents ‐ the case report number EXERCISE 3.11 Why are fingerprints a more valuable piece of evidence than fibres, pieces of glass etc? Of course if obvious or numerous fibres are found at the point of entry, on a victim's body, etc., then they should be collected in case no fingerprints of value are found. It is also wise to collect more evidence at a crime scene than not to collect enough evidence. An investigator usually only has one shot at a crime scene, so the most should be made of it. The following is a breakdown of the types of evidence encountered and how the evidence should be handled. Impression evidence such as fingerprints, bite marks, toolmarks, tyre and footprints is a specialist area which will be covered separately in the next chapter. However, scale photographs of the impressions should be taken before any attempt is made to lift or replicate them, Blood and bodily fluids Dry and wet bodily fluid residues need to be treated differently. DRIED STAINS If the stained object can be transported back to the crime lab, then package it in a paper bag or envelope and send it to the lab. If not, then either use fingerprint tape and lift it like a fingerprint and place the tape on a lift back; scrape the stain into a paper packet and package it in a paper envelope; or absorb the stain onto 1/2" long threads moistened with distilled water. The threads must be air dried before permanently packaging. For transportation purposes and to prevent cross contamination, the threads may be placed into a plastic container for no more than two hours. Once in a secure location, the threads Crime Scene Processing 3.15 3. Processing the crime scene must be removed from the plastic and allowed to air dry. They may then be repackaged into a paper packet and placed in a paper envelope. WET All items should be packaged separately to prevent cross contamination. If the item can be transported to the crime lab, then package it in a paper bag (or plastic bag if the transportation time is under two hours), bring it to a secure place and allow it to thoroughly air dry, then repackage it in a paper bag. If not, then absorb the stain onto a small (1"x1") square of pre‐cleaned 100% cotton sheeting. Package it in paper (or plastic if the transportation time is less than two hours), bring it to a secure place and allow it to thoroughly air dry; then repackage it in a paper envelope. EXERCISE 3.12 Give examples of items of evidence likely to have bodily fluids on them that: could be transported back to the lab could not be transported back to the lab Questioned documents Known examples of the suspected person's handwriting must be submitted for comparison to the unknown samples. Questioned documents can also be processed for fingerprints. All items should be collected in paper containers. Firearms, bullets & casings and other weapons Firearm safety is a must at any crime scene. If a firearm must be moved at a crime scene, never move it by placing a pencil in the barrel or inside the trigger guard. Yes, this happens on TV, but not only is it unsafe, but it could damage potential evidence. The gun can be picked up by the textured surface on the grips without fear of destroying useful fingerprints on the weapon. Before picking up the gun, make sure that the gun barrel is not pointed at anyone. Keep notes on the condition of the weapon as found and stops taken to render it as safe as possible without damaging potential evidence. The firearm can then be processed for prints and finally rendered completely safe. Firearms must be rendered safe before submission to the crime lab. The firearm should be packaged in an envelope or paper bag separately from the ammunition and/or magazine. The ammunition and/or magazine should be placed in a paper envelope or bag. It is important that the ammunition found in the gun be submitted to the crime lab. Any boxes of similar ammunition found in a suspect's possession should also be placed in a paper container and sent to the crime lab. Casings and/or bullets found at the crime scene should be packaged separately and placed in paper envelopes or small cardboard pillboxes. If knives (or other sharp objects) are being submitted to the lab (for toolmarks, fingerprints, serology, etc.), then the blade and point should be wrapped in stiff unmovable cardboard and placed in a paper bag or envelope. The container should be labelled to warn that the contents are sharp and precautions should be taken. Crime Scene Processing 3.16 3. Processing the crime scene Hair Hair found at the scene should be placed in a paper packet and then placed in an envelope. If a microscopic examination is required, then 15‐20 representative hairs from the suspect must be submitted to the lab for comparison. If DNA analysis if going to be used, then a whole blood sample from the suspect must be submitted to the lab in a "Vacutainer." Fibres Fibers should be collected in a paper packet and placed in an envelope. Representative fibers should be collected from a suspect and submitted to the lab for comparison. Paint Paint fragments should be collected in a paper packet and placed in an envelope. Representative paint chips or samples should be collected from the suspect and submitted to the lab for comparison. Glass Smaller glass fragments should be placed in a paper packet and then in an envelope. Larger pieces should be wrapped securely in paper or cardboard and then placed in a padded cardboard box to prevent further breakage. Representative samples from the suspect should be submitted to the lab for comparison. Presumptive tests It would be embarrassing as well as expensive in terms of time to detail an apparent bloodspatter pattern photographically and on your sketch only to find out later that someone had an accident with a bottle of tomato sauce. Don’t leap to the conclusion that every reddish spot at a crime scene, even one where there are obvious pools of blood leaking from out from under a victim, is blood. Likewise, every white powder found in a plastic or foil packet is not heroin or cocaine. There are simple on‐the‐spot (pun intended) tests that can be done to check that what is presumed to be potential evidence is likely to be that. These are known as presumptive tests, and they are the forensic equivalent of a functional group test in organic chemistry. They are designed to be: quick simple sensitive provide a visual result EXERCISE 3.13 Why are these requirements important? quick simple sensitive provide a visual result Unfortunately, meeting these practical requirements tends to have a important consequence: few if any presumptive test are totally specific. This means that they will give a positive test for materials other than the intended one. This is known as a false positive. Crime Scene Processing 3.17 3. Processing the crime scene EXERCISE 3.14 Given the potential for false positives, what conclusion can you draw from: a positive test a negative test Do you think this limitation is a problem? TESTS FOR BLOOD For many years, the most commonly used reagent for the identification of blood was benzidine (diamobiphenyl), but was been determined to be carcinogenic, and its use was discontinued. It was replaced by the Kastle‐Meyer (K‐M) test, which is based on phenolphthalein. Both these tests are really testing for haemoglobin, which acts as a catalyst to accelerate the oxidation of the reagent by peroxide. The K‐M test uses a reduced form of phenolphthalein (heated with zinc powder) in alkaline solution. The test sample is treated with the phenolphthalein, and then hydrogen peroxide added. A positive colour is indicated by the familiar purple of phenolphthalein. If a colour develops before the peroxide is added, then this is a negative result – something else is reacting with the PP, not the blood, which requires the peroxide. There are few substances which mimic the action of haemoglobin – potatoes and horseradish – but their occurrence at a crime scene is fairly unlikely (unless it is a Japanese restaurant or fish & chip shop). The other common reagent these days is luminol, which is much more sensitive than the K‐M test, but is based on fluorescence and therefore requires a UV light source and darkened conditions. All tests for blood should be done in conjunction with a control, which is a sample from a related but not suspect items, eg a part of the wall where no blood should be. If a positive result is achieved from the control, then something in the sample background is causing a problem, and results from the real samples cannot be taken seriously. TESTS FOR ILLICIT DRUGS Faced with the prospect that a white powder could be any of a thousand illegal drugs or something totally benign, a lot of time can be saved by a series of tests that generate colour in the presence of different pharmaceuticals, as shown in Table 3.1. TABLE 3.1 Presumptive tests for illicit drugs Test Marquis Dillie‐Kopanyi Duquenois‐ Levine Van Urk Scott Colour (+ve test) purple orange‐brown violet‐blue purple blue‐purple blue Drug classes opium derivatives amphetamines, methamphetamines barbiturates marijuana LSD cocaine Crime Scene Processing 3.18 3. Processing the crime scene Latent fingerprints Latent fingerprints are those which are invisible to the naked eye, and are the residue pattern of the oils from our skin left behind when a smooth surface is touched by the fingerpad. To make them useful for the identification of people at a crime scene requires a three‐step process: 1. finding them 2. making them visible 3. recording or transporting them Detecting the presence of the prints is generally done by the use of a UV light. The most common employed crime scene unit is known as a Polilight (see picture) and is an Australian invention from the forensic science unit at the Australian National University. The intense UV beam produces fluorescence from the fingerprints (as well as invisible bloodstains, impressions on writing pads etc). With regard to fingerprints, it helps identify full prints which are useable, compared to partial or smeared prints, which are not any further effort. Visualising the prints so that a permanent record can be made uses physical (powder) or chemical (colour‐forming) treatment. Which one is used depends on the type of surface that the print is on. If it is hard and non‐porous (eg glass, metal), powder (or the SupaGlue vapour method) is the choice; if porous (eg paper) then chemical treatment is needed. Everyone has heard a TV cop say “we’ll have to wait until they finish dusting for prints”! There are numerous powders that have been used for dusting prints, from plain charcoal and talcum powder up to expensive proprietary blends. The most important determining factor is the colour of the surface. Some level of contrast is needed – black powder on a black car is not going to work. EXERCISE 3.15 Why is contrast required for dusting powders? Dusting a fingerprint so that it is useable is not easy and requires substantial practice to get right. The print can be “drowned” in powder or the fragile impressions damaged by brushstrokes. The expert’s tips for dusting prints successfully Shake the brush so the bristles spread apart. Dip the tip of the brush in the powder, and then gently tap the brush's handle to remove excess powder. Run the brush's bristles lightly over the print surface in short and quick strokes. As the print begins to appear, use the brush to trace along the ridge lines. With the dust having adhered to the print, it now needs to be lifted, which means removing it from the surface adhering it to a new transportable surface without destroying it. This too requires practice. Because of the potential for wrecking the print in the lifting process, it should be photographed at as close to 1:1 as possible (with a scale next to it). The oldest method for this uses transparent sticky tape, and there are hinged lifters – a plastic protective sheet over a sticky pad – which achieve the same end. Crime Scene Processing 3.19 3. Processing the crime scene The procedure for lifting a print with tape A 6‐8 cm length of tape is pulled clear and straight (no kinks) from the roll, but not cut from it. The end of the tape is folded over to provide a “handle”. A bit of tape is folded over to be used as a tab for handling and the tape is unrolled. The tape is secured to the surface about 2‐3 cm on the far side of the print. The tape is gently rubbed over the print. After the tape is firmly in place, the print is lifted by pulling the roll gently and evenly away from the surface. The tape is then quickly applied to a card and excess tape must then be cut away. The SupaGlue method uses heated cyanoacrylate vapour from the glue in a sealed chamber or more recently with the use of a special “wand” which generates the vapour. This reacts with the moisture in the print and produces a permanent and more stable (than the powdered) record. Various chemical treatments are used for visualising prints on adsorbent surfaces, such as paper. These include iodine, ninhydrin and silver nitrate. The prints are not removed from the surface, but can be photographed at as close to 1:1 as possible (with a scale next to them). What You Need To Be Able To Do define important terminology list the actions involved in processing a crime scene describe search patterns for crime scenes describe methods for documenting a crime scene produce photographs and video footage of a crime scene describe methods for collecting and packaging different evidence types explain the principle behind presumptive tests list common presumptive tests for blood and drugs Crime Scene Processing 3.20