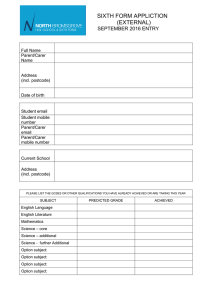

14-19 Education and Skills

advertisement