Jack Sharples University of Glasgow PhD Student 2008-2012

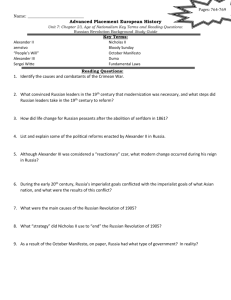

advertisement