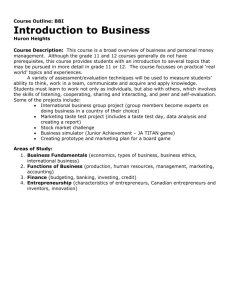

No. 41

advertisement