EN301: Shakespeare and Selected Dramatists of his Time

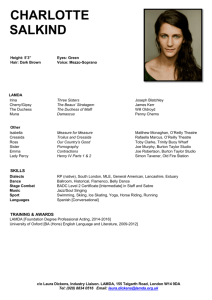

advertisement

EN301: Shakespeare and Selected Dramatists of his Time The two 1609 Quarto title pages The 1609 Epistle “Eternall reader, you have here a new play, never stal’d with the Stage, never clapper-clawed with the palmes of the vulgar… refuse not, nor like this the lesse, for not being sullied, with the smoky breath of the multitude…” Troilus and Cressida, Or, Truth Found Too Late Written by John Dryden for the Duke’s Theatre, London, in 1679. Dryden’s third and final Shakespeare adaptation Reduces cast Re-orders scenes (avoids “leaping from Troy to the Grecian tents, and thence back again in the same Act”) Makes Cressida faithful to Troilus Follows an explicitly Aristotelian model of tragedy, adding death scenes for the title characters Dryden’s Preface Dryden describes himself as having “undertaken to correct” Shakespeare’s play, largely to bring it in line with neo-classical tastes: “I undertook to remove that heap of rubbish, under which many excellent thoughts lay wholly buried”. “Accordingly, I new-modelled the Plot; threw out many unnecessary persons; improved those characters which were begun, and left unfinished, as Hector, Troilus, Pandarus and Thersites; and added that of Andromache.” Dryden objects that in Shakespeare, “Cressida is false, and is not punished”; by contrast, Dryden’s Cressida is innocent. “...the characters which should move our pity ought to have virtuous inclinations, and degrees of moral goodness in them”. Dryden’s legacy Dryden’s adaptation was revived numerous times in the early 18th century between 1709 (at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane) and 1734 (at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden). There are no known productions of Troilus and Cressida on record from 1734 until 1898 (when it was performed in Munich). Whenever theatrical productions were contemplated during this time, Dryden’s adaptation seems to have been the template: The actor-manager John Philip Kemble re-ordered Shakespeare’s text into a scenic structure closer to Dryden’s when he started work on an eventually unrealised production around 1800; A manuscript adaptation by ‘R. J.’ in 1810 combined Dryden and Shakespeare. Numerous productions since have followed Dryden in adding death scenes for Troilus and/or Cressida. Cressida in Dryden Dryden’s version of 1.2 cuts a lot of Cressida’s interjections, quibbling and backchat Cressida’s soliloquy, which closes the act in Dryden, is rewritten to make her less strategic and almost puzzled at her own actions: Shakespeare’s Cressida: Words, vows, gifts, tears, and love’s full sacrifice He offers in another’s enterprise; But more in Troilus thousandfold I see Than in the glass of Pandar’s praise may be. Yet hold I off. Women are angels, wooing; Things won are done. Joy’s soul lies in the doing. That she beloved knows nought that knows not this: Men prize the thing ungained more than it is. That she was never yet that ever knew Love got so sweet as when desire did sue. Therefore this maxim out of love I teach: Achievement is command; ungained, beseech. Then though my heart’s contents firm love doth bear, Nothing of that shall from mine eyes appear. (1.2.260-72) Dryden’s Cressida: A strange dissembling sex we women are; Well may we men, when we ourselves deceive. Long has my secret soul loved Troilus. I drunk his praises from my Uncle’s mouth, As if my ears could ne’er be satisfied; Why then, why said I not I love this Prince? How could my tongue conspire against my heart, To say I loved him not? O childish love! ’Tis like an infant froward in his play, And what he most desires, he throws away. Cressida in Dryden Shakespeare’s Cressida: Dryden’s Cressida: TROILUS. O Cressida, how often have I wished me thus. CRESSIDA. Wished, my lord? The gods grant,--O, my lord! TROILUS. What should they grant? What makes this pretty abruption? What too-curious dreg espies my sweet lady in the fountain of our love? CRESSIDA. More dregs than water, if my fears have eyes. […] Blind fear, that seeing reason leads, finds safer footing than blind reason stumbling without fear. To fear the worst oft cures the worse. […] They say all lovers swear more performance than they are able, and yet reserve an ability that they never perform: vowing more than the perfection of ten, and discharging less than the tenth part of one. They that have the voice of lions and the act of hares, are they not monsters? (3.2.59-82) TROILUS. O Cressida, how often have I wished me here! CRESSIDA. Wished, my lord? The gods grant,--O my lord! TROILUS. What should they grant? What makes this pretty interruption in thy words? CRESSIDA. I speak I know not what! The scene that follows is heavily edited to remove all Cressida’ doubts about Troilus. Dryden adds in a bit where Cressida repeatedly insists that she won’t go to bed with Troilus without a promise “that the holy Priest / Shall make us one for ever”… Dryden’s Cressida Between Shakespeare’s 5.1 and 5.2 Dryden adds a short but crucial dialogue between Calchas and Cressida in which Calchas instructs his daughter to “dissemble love to Diomede still” in order to put him off his guard and better facilitate their escape back to Troy; he tells her specifically that she must give up Troilus’ ring in order to be more convincing. At the climax, Troilus refuses to believe her account of this, and as she protests she “but dissembled love” to Diomedes, Diomedes produces the ring as evidence to the contrary. Troilus damns her to hell, and she, heartbroken, stabs herself. “Oh, can you yet believe, that I am true?” she asks as she dies; Troilus is convinced by her desperate action of her “purest, whitest innocence”, though “too late I know it”. He curses himself, but she blesses him with her dying breath, and her last line is “I die happy that he thinks me true”. “Correcting” Cressida R. J.’s 1810 manuscript adaptation mostly follows Dryden, but departs from both sources at the end of the lovers’ first scene together, when he adds a final speech for Troilus affirming that Priam and Hecuba have approved their marriage (there is no suggestion in R. J.’s version that Troilus and Cressida actually sleep together). He then adds a completely new marriage scene between Troilus and Cressida set in the Temple of Hymen at Troy. “Correcting” Cressida Cutting Cressida’s lines in order to make her less complex seems to have been common practice in early 20th-century productions. The first professional American production in 1932, for example, cut several of Cressida’s bawdy lines in 1.2, much of her soliloquy in that scene (discussed above), and the entirety of her last soliloquy: CRESSIDA. Troilus, farewell. One eye yet looks on thee, But with my heart the other eye doth see. Ah, poor our sex! This fault in us I find: The error of our eye directs our mind. What error leads must err. O then conclude: Minds swayed by eyes are full of turpitude. (5.2.107-12) “Correcting” Cressida Bridget Escolme gives a good sense of what may be lost with cuts of this sort, speculating about “the meanings that might be produced by a Cressida who makes eyes at us, who directly elicits the audience’s approval for her actions or defies their disapproval of them” (2005: 39). She notes that when, in a workshop, a student Cressida began addressing the audience, “[t]he student spectators began to judge themselves rather than Cressida’s morality, suddenly aware of their own role in the production of meaning. They commented that they had been let into a secret by Cressida and enjoyed the sense of power that this conferred. The idea that Cressida, or the performer - and the fact that it was unclear ‘who’ is significant - was flirting with them, was enjoyable rather than reprehensible as it had been when the character had been judged a flirt within a fictional locus.” (2005: 45) Playing Cressida Dryden cuts the crucial scene in which Cressida arrives at the Greek camp and is kissed by the commanders before being condemned by Ulysses as “wanton”: ULYSSES. Fie, fie upon her! There’s language in her eye, her cheek, her lip; Nay, her foot speaks. Her wanton spirits look out At every joint and motive of her body. O these encounterers so glib of tongue, That give accosting welcome ere it comes, And wide unclasp the tables of their thoughts To every ticklish reader, set them down For sluttish spoils of opportunity And daughters of the game. (4.6.55-64) To what extent does a production ask us to agree with Ulysses? Playing Cressida For Robert Kimbrough, the speech is “almost a stage direction to one playing Cressida’s role” (1964: 79). Indeed, many early 20th-century productions seem to have endorsed this view if reviewers’ accounts can be trusted. Cressida has been, for example: “mincing, detestable” and “repulsive” (The Times, 11 December 1912) “sighing, designing, crafty and fluffy” (The American, 7 June 1932) “a modern wanton” (Morning Legend, 28 April 1956) Director Tyrone Guthrie called the character “a minx… a witty, flirtatious, highly sexed creature”: “She is also an opportunist, but in circumstances where opportunism is understandable and forgivable.” (director’s notes, 1956) This view of Cressida was emblematised in John Barton’s 1976 production of the play for the RSC, when Francesca Annis’s Cressida was “symbolically disrobed” as she arrived at the Greek camp and “metamorphosed into a Greek courtesan” (Rutter 2001: 129), the “assured sexual specialist whom Ulysses instantly recognises” (The Times, 18 August 1976). Playing Cressida For director Joseph Papp, however, Troilus was “the greatest offender against decency” in the play and Cressida was “his victim”: “I felt he applied a double standard in honour, and to me this was immoral” (1967: 24). Papp saw the scene in which Cressida is kissed by the Greeks as tantamount to a sexual assault and directed it as such for his 1965 production; indeed, many productions now play it in this manner. Papp makes a useful point about the timing of Cressida’s exit from this scene: “In the case of Cressida leaving the stage with Diomedes, we hear Ulysses’ speech about her while she is still in motion. It is interesting to observe her walking off as Ulysses characterises her movement.” (1967: 63) Thersites Dryden tends to downplay the role of Thersites in his adaptation (though he is given a very political epilogue). Dryden adds a scene in which Ulysses manipulates Thersites into provoking an argument between Ajax and Achilles; this means that later in the play, Thersites’ mockery of Ajax is more clearly part of Ulysses’ plan. Thersites is also more clearly wrong in Dryden, as he interprets Cressida as a “strumpet” and a “whore”. Act Five Scene Two presents the battle not from Thersites’ perspective but from Agamemnon’s. Thersites as war correspondent In Michael Macowan’s production (1938), Thersites was a scruffy and cynical left-wing journalist, acting as a commentator on the play (he delivered the prologue whilst smoking a cigarette). This was a decision that Macowan felt was “justified by Shakespeare’s having made him the mouthpiece for his own bitterness and torment of spirit” (programme notes). Dorothy L. Sayers wrote to The Times in response to their review of this production: “…here is the great “war-debunking” play, whose savage bitterness has never been equalled before or since. … If ever there was a play for the times, it is this.” (24 September 1938) Thersites as war correspondent In 1956, director Tyrone Guthrie set the play in the years leading up to World War 1: “One of its important premises is that war is sport, a gallant and delightful employment, indeed the only suitable employment for young men of the Upper Class. This is a premise to which no one nowadays can possibly subscribe. Therefore we have set the play back to a date when such a view was still widely held but as near as possible to our own times: namely just before 1914.” (Director’s notes) In this production, according to Ralph Berry, Thersites was “a war correspondent, constantly setting up his box camera on a tripod. This brings out the voyeurism, together with the radical discontent of the man” (1981: 55). Alan Brien remembered the latter as “as a drunken war correspondent scribbling gossip —'they say he keeps a Trojan drab'…” (Spectator, 28 July 1960). Female Thersites William Poel’s 1913 production had a female Thersites in a jester’s costume. In 2012, the Maori production that visited Shakespeare’s Globe for the Globe to Globe festival likewise had a female actor, Juanita Hepi, as Tēhiti (Thersites): “Hepi’s Tēhiti carried the same taiaha as the men, but treated it with satirical disdain; as a woman, she was able to mimic and pastiche the other characters’ masculine behaviour without relinquishing her own gender identity. Her parody of Āhaka’s (Ajax’s) ultra-macho posturing was acutely observed.” (Purcell 2013: 211) Female Thersites The American Shakespeare Center’s 2013 production likewise had a female Thersites. Allison Glenzer’ s Thersites was alone in an otherwise historically-costumed production in wearing anachronistic shoes (black converse-style sneakers), and got frequent rounds of applause from the audience for her comic turns (for example, her mockery of Ajax). But there were serious resonances too: Thersites’ frequent use of the word “whore” sounded more ironic from the mouth of a female performer, and Glenzer’s doubling as Cassandra provoked an unexpected parallel (both characters are reviled or ignored truthtellers). Masculinity Honour is more gendered in Dryden’s 2.1 (Shakespeare’s 2.2): Shakespeare’s “theft most base” (91) becomes “unmanly theft”; Paris’s “sweet delights” (142) become “effeminate joys”. Compare: Shakespeare’s Troilus: Why, there you touched the life of our design. Were it not glory that we more affected Than the performance of our heaving spleens, I would not wish a drop of Trojan blood Spent more in her defence. (2.2.193-7) Dryden’s Troilus: Why there you touched the life of our design: Were it not glory that we covet more Than war and vengeance ( beasts’ and women’s pleasure) I would not wish a drop of Trojan blood Spent more in her defence. Masculinity Dryden adds some new passages to hammer the point home: Andromache says “I would be worthy to be Hectors wife: / And had I been a Man, as my Soul’s one / I had aspir’d a nobler name, his friend”; Hector replies, “Come to my Arms, thou manlier Virtue come; / Thou better Name than wife!”. When Priam admits he is fearful, Andromache admonishes him with “There spoke a woman, pardon Royal Sir”. At the end, Troilus laments for Cressida “like a woman” and is about to kill himself when manliness takes over again and he fights Diomedes to the death, only to be killed himself by Achilles. Masculinity Does this reveal an anxiety about Shakespeare’s own presentation of masculinity? For Joseph Papp, the play “demonstrates that the superior posture of the male and his distorted attitudes towards women and war lead to folly and his ultimate destruction” (programme notes, 1965). As Carol Rutter has put it: “Male politics in Troilus and Cressida needs the woman, needs her, mystified, to legitimate its practices; needs her, objectified, to serve its objectives.” (2001: 122) Masculinity Achilles and Patroclus especially blur the boundaries of heteronormative constructions of masculinity: Patroclus notes that he is “condemned” as “an effeminate man / In time of action”, urging Achilles, “Sweet, rouse yourself” (3.3.211-15). Achilles admits to “a woman’s longing, / An appetite that I am sick withal, / To see great Hector in his weeds of peace, / To talk with him and to behold his visage / Even to my full of view” (3.3.230-4). Thersites calls Patroclus “Achilles’ male varlet… his masculine whore” (5.1.14-16). Masculinity John Barton’s 1968 production featured an Achilles in drag: Alan Howard donned a blonde wig and a dress in an impersonation of Helen in order to meet Hector during the truce, and then to tease Menelaus as the party began. Barton said he saw Achilles “as bisexual, a view which is surely embodied in Shakespeare’s play and is also the view which the Elizabethan audience would have taken” (Lloyd Evans 1972: 70). It is significant that Barton’s production was staged in 1968, one year after the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the UK and just before the end of stage censorship. Simon Shepherd has criticised the production as “an essentially heterosexist association of drag with unhealthy self-indulgence” (1988: 108). Drag For his 1981 TV production, Jonathan Miller cast drag performer The Incredible Orlando (Jack Birkett) as Thersites. David Suchet’s Achilles cross-dressed at one point in Terry Hands’ 1981 RSC production. Pandarus was a drag queen in Ian Judge’s 1996 RSC production. In Cheek by Jowl’s 2008 production, Thersites first appeared in drag as a cleaning lady (making sense of Ajax’s “Mistress Thersites”) before returning to entertain the troops as a something like a Marlene Dietrich tribute act. Achilles, Patroclus and Thersites all wore drag in the 2012 RSC/Wooster Group co-production. Order Dryden opens his Act One with Shakespeare’s 1.3, and Act Two with Shakespeare’s 2.2, meaning that Agamemnon and Priam are the first speakers of each act respectively. His first scene concludes with a speech in which Agamemnon gives explicit instruction to Ulysses and Nestor to “put a stop to these encroaching ills” and “vindicate the dignity of Kings” (thus removing some of that plot’s subversive potential). Similarly, the play is refashioned into a parable of dutiful obedience to authority in its closing speech: ULYSSES. Now peaceful order has resumed the reins; Old time looks young, and nature seems renewed. Then since from homebred factions ruin springs, Let subjects learn obedience to their Kings. Indeed, for Shakespeare’s Ulysses, the root of the Greeks’ problems is that “The specialty of rule hath been neglected”: ULYSSES. The heavens themselves, the planets, and this centre Observe degree, priority and place, Infixture, course, proportion, season, form, Office and custom, in all line of order. […] But when the planets In evil mixture to disorder wander, What plagues and what portents, what mutiny? What raging of the sea, shaking of earth? Commotion in the winds, frights, changes, horrors Divert and crack, rend and deracinate The unity and married calm of states Quite from their fixure. O when degree is shaked, Which is the ladder to all high designs, Then enterprise is sick. […] Take but degree away, untune that string, And hark what discord follows. […] The general’s disdained By him one step below; he, by the next; That next, by him beneath. […] And ’tis this fever that keeps Troy on foot, Not her own sinews. (1.3.85-136) E.M.W. Tillyard saw Ulysses’ speech as indicative of an “Elizabethan World Picture” shared by the whole society, a conception of order that was “so taken for granted, so much part of the collective mind of the people, that it is hardly mentioned except in explicitly didactic passages” (1963: 18). Then-Chancellor of the Exchequer Nigel Lawson on this speech in 1983: “The fact of differences, and the need for some kind of hierarchy, both these facts, are expressed more powerfully there than anywhere else I know in literature. … Shakespeare was a Tory, without any doubt.” (Guardian, 5 September 1983) In 1994, Michael Portillo (then Chief Secretary to the Treasury) used the speech to illustrate how “order in society depends upon a series of relationships of respect and duty from top to bottom”, and to condemn a “New British Disease: the self-destructive sickness of national cynicism”: “If Crown, Parliament and Church are not respected, neither will be law, judges or policemen, nor professors nor teachers nor social workers, nor bosses, managers or foremen. Social disorder follows when respect breaks down.” (Independent, 16 January 1994) The Ulysses speech is also cited in The Faber Book of Conservatism (ed. Keith Baker, 1993, pp. 19-20). Order But as Margo Heinemann points out, “Ulysses may talk about the sacredness of hierarchy and order, but the setting shows him as a cunning politician whose behaviour undercuts what he says here, as indeed does the whole play” (1994: 227). Indeed, we might think forward to Ulysses’ own deliberate flouting of “degree”: ULYSSES. Let us like merchants show our foulest wares And think, perchance, they’ll sell. […] No, make a lott’ry, And by device let blockish Ajax draw The sort to fight with Hector. Among ourselves Give him allowance as the worthier man. (1.3.352-70) Order In Mark Wing-Davey’s 1995 production, 1.3 started with soldiers watching a TV news report about the Bosnian war (“near Sarajevo, the UN rapid reaction force is increasing the deployment…”) Ulysses switched the TV back on for “But when the planets…”, flicking through channels to illustrate the “raging of the sea, shaking of earth[,] /Commotion in the winds, frights, changes, horrors…” (1.3.94-8). He gestured to himself, interestingly, on “him one step below” (1.3.130); later, he fully and obscenely mimed all of Patroclus’ “scurrile jests” (1.3.148), paradoxically doing the very thing he was supposedly condemning. Order By 2012, Portillo (now really a broadcaster rather than a politician) had rather different things to say about the play… My Own Shakespeare, Michael Portillo, BBC Radio 4, 21 May 2012 (http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p02r58gb) References Berry, Ralph (1981) Changing Styles in Shakespeare, London, George Allen & Unwin. Escolme, Bridget (2005) Talking to the Audience: Shakespeare, performance, self, London and New York: Routledge. Heinemann, Margo (1994) ‘How Brecht read Shakespeare’, in Jonathan Dollimore and Alan Sinfield [eds] Political Shakespeare: Essays in Cultural Materialism, 2nd edition, Manchester: M. U. P. Kimbrough, Robert (1964) Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida and its Setting, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Lloyd Evans, Gareth (1972) ‘Directing Problem Plays’, Shakespeare Survey 25, 63-72. References Papp, Joseph (1967) ‘Directing Troilus and Cressida’ in Bernard Beckerman and Joseph Papp [eds] The Festival Shakespeare: Troilus and Cressida, New York: Macmillan, 23-72. Purcell, Stephen (2013) ‘Troilus and Cressida’ in Paul Prescott and Erin Sullivan [eds] A Year of Shakespeare, London: Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare, 210-12. Rutter, Carol Chillington (2001) Enter the Body: Women and Representation on Shakespeare’s Stage, London: Routledge. Shepherd, Simon (1988) ‘Shakespeare’s Private Drawer: Shakespeare and Homosexuality’ in Graham Holderness [ed.] The Shakespeare Myth, Manchester: M. U. P., 96-110. Tillyard, E. M. W. (1963) The Elizabethan World Picture, Harmondsworth: Penguin.