Wage Growth in the Civilian Careers of Military

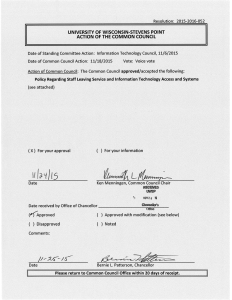

advertisement