Document 12697866

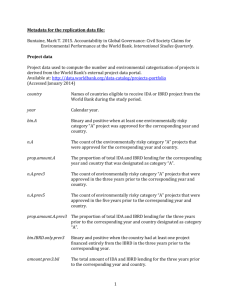

advertisement