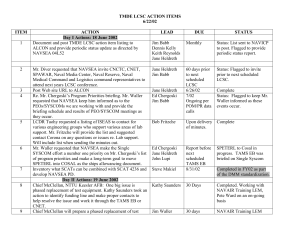

NAVSEA MARKETS AND THE PRODUCTS AND ACTIVITIES TO FULFILL THEM

advertisement