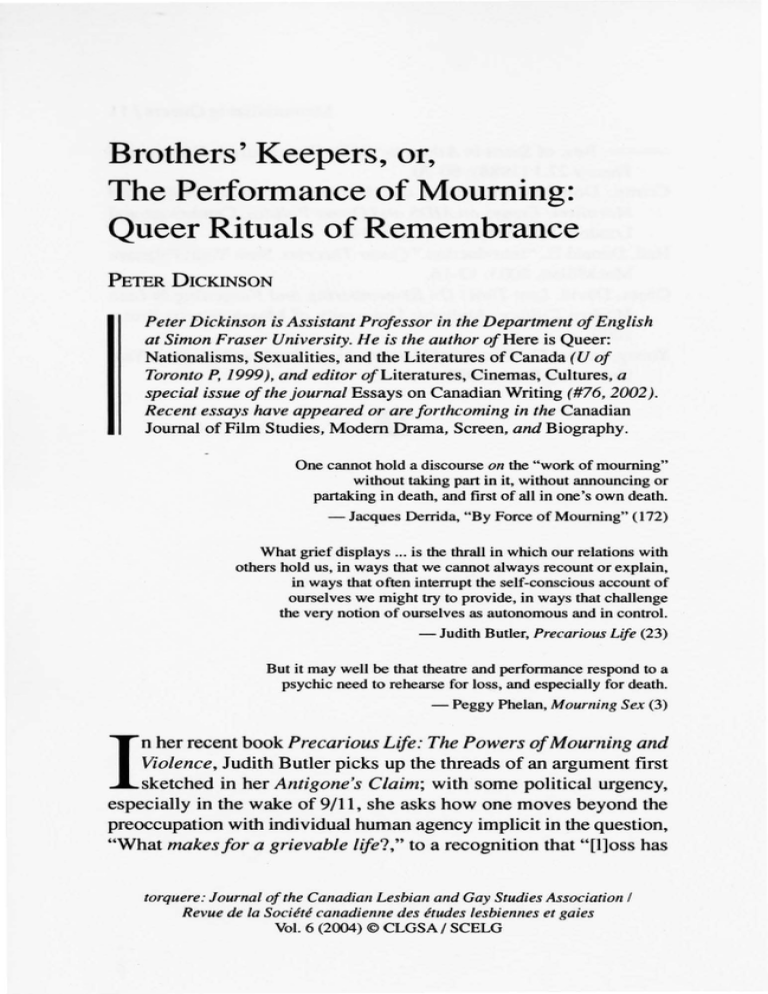

Brothers' Keepers, or, The Performance of Mourning: Queer Rituals of Remembrance

advertisement