‘Stating the bleeding obvious’: An Interview with John Goodby on... Poetry of Shame Barry Sheils and Julie Walsh

advertisement

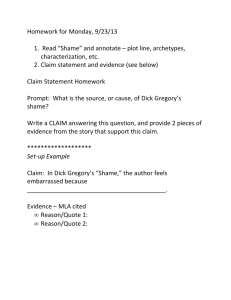

‘Stating the bleeding obvious’: An Interview with John Goodby on the Poetry of Shame Barry Sheils and Julie Walsh We’re over an hour into our interview when the poet John Goodby’s phone rings: ‘Who’s going to say it first?’ someone ventures, trusting that all minds have reached for the same cliché. The digital recorder is paused. Everyone in the room, it seems, shares a degree of relief at escaping momentarily from the formality of the interview, and yet there is also an underlying sense that we’ve been caught out, burst-in on; that the innocent interruption by a social call is somehow accusatory. Are we perhaps, as living proof of our subject matter, ashamed? John Goodby is a poet, translator and academic at Swansea University whose critical works include Irish poetry since 1950: from stillness into history (2000) and The Poetry of Dylan Thomas: Under the Spelling Wall (2013). He has a new Collected Poems of Dylan Thomas in press for this centenary year. John has published several collections of poetry, including The Birmingham Yank (Arc, 1998), uncaged sea (Waterloo Press, 2008) and A True Prize (Cinnamon, 2011). We wanted to talk to John about his 2010 collection Illennium which foregrounds the theme of shame. Praised for its irreverence and ‘shameless’ eroticism, Illennium ‘traces the trajectory of a single attachment within a tangled set of friendships.’ John agreed to talk to us about his work earlier this year. The collection is a cut-up sonnet sequence indebted to the work of the American poet Ted Berrigan. Its promiscuous intertextuality moves across cultures, languages, and academic disciplines, incorporating theoretical and sociological works on shame with the same élan as it does canonical works of poetry. It became apparent in our conversation that there was an affinity to be discerned between the work of the poet who delights in the dissemblance of language, and the productive dynamic of the shame affect. We were interested to hear from John about how his feelings of shame provided the impetus for the collection, and keen to speculate with him on the ways in which shame and writing may be culturally configured around questions of class, sexuality, ethnicity, and the politics of identity more widely. The Shame of Identity BS: John, in Illennium you include a glossary in which you list the Welsh words for shame [cywilydd] and embarrassment [annifyr]. You also use the Scottish or Ulster-Scots term ‘scundered’ in the poem itself. Reading this, I was reminded of the introduction to 1 Christopher Ricks’s book Keats and Embarrassment where he speaks about embarrassment as a specifically English word; or a word with specific prominence in the English tradition. I’m wondering, then, whether in your work you’re trying to move away from the Englishness of embarrassment at all? Perhaps there are different cultures of embarrassment? JG: You’re absolutely right, I think, in saying that my engagement with embarrassment the poetics of embarrassment- is a way of, (you’re not actually saying this), but of not being English, or of challenging Englishness. That is what it’s about for me, I suppose. It’s no coincidence that I happen to be working on Dylan Thomas even though I’m not Welsh. I’ve also been trying to put together an anthology of experimental Welsh poetry because a lot of it is small press or it’s out of print. University of Wales Press are interested in a way, but it’s a lacuna in their knowledge, so there’s an embarrassment there and maybe a guilt and I’m not sure quite what the size of it is. But this is something that interests me; not just the role of guilt or shame or embarrassment in terms of individual writing, but in terms of the constitution of traditions and the critical discourses that surround the poetic traditions and the ways we define poetry. These two things interact, they’re not separate; they determine what you can write or what you’re embarrassed about writing, or the styles you’re embarrassed at writing in, let’s say. BS: And on Englishness… JG: The English conception of embarrassment worries me and irks me. I suppose, in some ways, embarrassment -or the control of emotion and embarrassment about letting it show- is a class marker. The working class get hysterical, passionately excited, lose themselves in riots, mobs and so on, in football crowds, or they emote to cheap pop music. But the upper-middle classes and the upper classes know how to control that, and that is what their power is based on. So control of embarrassment, narrowly defined, is a signal of class power and that’s one reason I’m interested in it. It goes back to my politics, I suppose, a long way in the past, in the seventies, which are pretty Marxist, or Trotskyist. BS: And shameless? JG: Flagrantly so, yeah JW: Why so? The issue, as you presented it, the situation of class and controlling embarrassment, reminded me of the idea of ‘shame management’; controlling embarrassment; managing shame. And I was wondering where poetry happens, and whether the writing of Illennium was a process of shame management? How can you think about this process as a poetic subject and as a political subject? JG: You’re right: one of the things that occurred as I was writing this was the whole business of the lyric ‘I’; the ego in lyric poetry as something embarrassing, and the question of how you deal with that. Most mainstream poetry, it seems to me, doesn’t have too much of a problem with the ‘I’. What a poet usually does is establish a voice in their first collection; and it’s usually, post-1990s, a niche voice, quite well defined and reflective of the sort of consumerist society that we live in. There’s a lot of jostling for space in certain parts of the spectrum, but if the voice is defined then the poet goes on to write more out of that particular voice and about that particular area of experience. The ‘I’ remains stable within that, more or less, and it’s a stable self which uses tropes and conceits -the tricks of poetry, as it were- to dress up what is more or less a discursive utterance. This kind of writing does not really extend or take advantage of the existing possibilities of poetry and is therefore to be avoided. And yet my own kind of formation is bound up with that sort of poetry. In my first collection, Birmingham Yank, I suppose I’m using that standard, established voice, of the normal mainstream kind; a little to one side of it, perhaps, because the main influence there was a poet called Ian Duhig. He’s London-Irish, very interesting I think, in some ways quite gothic, to do with recondite and recherché histories, often connected with his London Irishness. After I finished that book, which was too bound by all these restraints that I’ve talked about -and in any case was fairly derivative in my case- I tried to find different ways of writing. In the past ten years or so I’ve experimented with different ways of presenting the self: not trying to eliminate embarrassment or shame, but to manage it, to use your word, in different ways. Although I don’t like the word management; and I notice that you put it in inverted commas when you used it. But, yes, I’ve tried to do that in Illennium and I tried to do it in a very different way in Uncaged Sea by simply using another text and applying a method for the selection of material from that text and its presentation [Uncaged Sea is “a mesostic rewriting of Dylan Thomas’s Collected Poems 1934-1952” published by Waterloo Press in 2008]. So it is an attempt to expunge the self in some more obvious post-Romantic ways, but the self always finds a way of creeping back in. I wanted it to creep back, and I’m interested in the form in which it would resurface. Illennium as you rightly intuited, had quite a lot to do with the essay I’d read by Thomas Scheff, ‘Shame as the Master Emotion of Everyday Life’. It made a lot of sense to me, partly because I’m quite an embarrassed person: when I was a child, I was the sort of person who’d just blush if they were introduced to a stranger, or whose eyes would water if they just walked past somebody in the street that they didn’t know. I was very, very, embarrassable. And part of growing up and being involved in academia, or political activity, is to do with overcoming that embarrassability. Of course there are questions about how far you overcome embarrassment without desensitising certain parts of yourself. Poetic Composition JW: When I read Illennium I was thinking about the process of writing it. I wondered if it felt like there was a doing of violence to yourself, which seems to me to be what shame can feel like? JG: It was hard to write, not only because of my own self but because I knew there were other people involved as well -and there’s a confessional aspect to it. It is a confessional poem but trying to avoid some of the pitfalls of confessionalism, let’s say. The material in there is the material of confessional poetry but it’s not presented in the manner of a Lowell or a Plath or a Berryman. It’s allowed to contradict itself but I think mainly, and I come back to your point about the violence, it’s allowed to articulate the incredible violence that you feel being done against yourself by what you’re undergoing; in other words, to be truer to the experience. To write in a discursive way about abjection in love is to falsify what’s going on, because, at a certain level, you feel torn up, you feel torn apart, and that was what I wanted to access. I wanted to get at that and to find a way of laying it out in the poems. BS: I’m wondering how this all works out in the process of composition: how you use cut-up, for example? JG: The model for this is Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets. The sonnet sequence from Sidney onwards, as you know, is usually a love sequence and often one which doesn’t have a happy outcome. That was the subject of Illennium, but Berrigan showed me how it might be possible to do that and not fall into the pitfalls of a normal confessional. The way that Berrigan seems to have done it, and he doesn’t really explain fully what his method is, is to have a nucleus of sonnets which are actually through-written, and make sense in a discursive way; and then he cuts them up and starts messing them around, taking just single-line phrases from them and interpolating them with other material. What I did when I was reading his book was colour-code the various phrases. I took my daughter’s crayons and tried to work out exactly how he’d done what he did. John shows us his copy of Berrigan’s The Sonnets with neat crayon highlighting throughout and numbers written finely in pencil beside the individual lines – I’ve used techniques that I know Berrigan used, and maybe come up with a few of my own. They would involve things like collaging chunks, single lines or phrases; random selection; or allowing sound-links to motivate the connections between the bits that I’ve got. Some of the sonnets will be more through-written than others, so some of them seem to make quite a lot of sense for quite a long time, for quite a number of lines, and then, puff, it just goes. Some of them are translations. The idea is to try and catch the unconscious mind and produce something which is… well, it might be charming, it might be delightful but it might be revealing as well, of something you couldn’t access in any other way. One of my inter-texts was Keats, because, as you also quite rightly surmised, the Ricks book was important to me. I teach Keats, or I did then, and Ricks has this fascinating investigation into the connection between embarrassment and blushing, but also the blood rushing to other parts of the body. So there’s a sort of phallic engorgement being linked to blushing; and that links in a nice way the blush that denotes maidenly purity, let’s say, and the blush which denotes an on rush of sexual desire. JW: What you said earlier was very interesting to me; the idea that somehow the process of writing a poem includes a commitment to try and outwit the conscious mind. I think, well, if that’s the project, then one is inevitably setting a trap for oneself. I was really struck when you opened Berrigan’s The Sonnets and we saw your colour coding. It reminded me of what sociologists do, and what methodologists do when they go about coding the world. There’s all that really mechanical, technical work... But I suppose what I’m most interested in is that we don’t get to see it in your poetry; we don’t get to see the background stuff when we read the sonnet on the page. JG: I know, and that sounds as though I’m withholding something, doesn’t it? JW: Well, only in as much as something must always be withheld I think -otherwise you have something that’s kind of uncontainable. JG: The process goes back to Eliot’s saying: ‘Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood’. Somewhere Eliot talks about the poet being a burglar who breaks into the house and has to somehow buy-off the guard dog. The guard dog here is the conscious mind, and so the poet has a nice bit of meat ready to give to the dog to shut it up while he goes about his burglaring business. At some level I want that to be happening here so the poem hits you as a sound structure, almost like reading the Rorschach blob, you know? The look of it on the page as well would be important – JW: Ah, like your Rorschach ink blot, Sonnet LIII? LIII am I am I I am i a an an h e hol e i t g u g e e r of the heart s he h a t ss r e e s th ol e I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the heart’s affections c r in g e in f ear n o thing but affect I t o n g u e lines I cr e at e certain of but ha I in fect am a n thing i s t art f i n JG: I was just thinking about that. There’s an Edwin Morgan poem, which you may have come across, called ‘I am the Resurrection and the Life’, and it breaks up that line from St John’s gospel to make various other short sentences or phrases from the individual letters in the line. It ends up with the complete line sort of thundering at the end. It’s an amazing poem. In my poem, I’ve put the whole line in the middle; it’s a line from one of Keats’s letters: ‘And I’m certain of nothing but the holiness of the heart’s affections’. I get it to say different things, contradictory things, things that deny or overturn that message, which is a very romantic one. JW: And coming back to this idea of trying to displace the coherent subject: here we have a pattern, a visual representation of that on the page. JG: You’re trying to disrupt the reading process so that meaning doesn’t get transmitted too easily or too cleanly, there’s got to be resistance there. And there’s pleasure in that, I think, for the reader; there’s a sort of pleasurable friction, you know? The Pleasure of Shame JW: Yes, it’s a pleasure that’s adjoined to frustration: something that has to be won, in relation to frustration I think. That’s kind of where shame is at, at least the way we’ve been thinking about shame in this project. It is our hypothesis through this project that there is pleasure in shame. Some people resist this idea but as soon as we think about the pleasure that can be allied to frustration and pain, then it seems to bear fruit. JG: Yes, the sequence is about concealment but it’s also about flaunting, absolutely it’s about flaunting, and there is also that aspect of illicit affection that the sequence comes out of. You have a feeling of invulnerability if you’re in the condition of being in love -or infatuated would be a better word, perhaps- and you think well, if people want to read it, they can, they can see it on me, in me; I’m not going to gabble about it but I’m not going to cover it up either. There is a condition of being for that kind of feeling, you know? As soon as you try and repress it or cover it up or adopt subterfuges, then you’ll destroy it anyway; you’ll make it go dirty and dark and all the rest of it - sorry to sound so Lawrentian, but that’s the nature of it as it affected me. There should be risk involved, let’s say, and I shouldn’t try to minimise that too much. I shouldn’t be totally secretive about it either. I’m starting mildly to blush now; you probably can’t see it in this light. But you can see the self-display or the flaunting of the relationship which is at work in the poetry, at the same time as you can see it being encoded and made difficult to read. So there are two processes going on at the same time, one of concealment, shameful concealment, and one of shameless self-display; and though I think the concealment is dominant it’s not necessarily dominant throughout. BS: Can we say of this sequence that it is an explication of the feeling of shame, then? That shame happens in these pages, or something along those lines? You use the phrase ‘the shame of shame’ I think. JG: I do. There is a point where the poem gets really knotted up with the technical writing on shame. I refer to the ‘master emotion of everyday life’: ‘As if it were shaming somehow to talk about shame- / Freud, Durkheim, Sennett and Elias too / were scundered…’ (Sonnet XXXVIII). There are others points where there’s that kind of knotting up. I think Sonnet XXXIV is probably the most obvious one; this is where it gets quite horribly abject with that rewriting of ‘since brass nor stone nor earth nor boundless sea’ from Shakespeare’s 65th sonnet. [John’s line runs: ‘Since bras nor stone gnaw earth, nor brazenry’]. Then you have ‘pudeur’, mutilation, curdling, the shamerage spiral, Kohut’s ‘narcissistic anger’, Goffman’s ‘facework’, Satir’s ‘levelling as cure’. I suppose it starts off as a sort of self-hatred and works its way towards a kind of mockery of sociological explanations for shame. XXXIV Since bras/s, nor a/s/tone, gnaw earth, nor brazenry but Dad morality foreslays there pudeur a slave no salve an Ordure, First Class, I for an I in the very temple of delight Out/r/age of need, of mutilés, of shame, rage at shame, shame at rage, curdled w/ho(?)-humiliated fury, the shame-rage spiral. Shameloose puce, madder. Rawled-without-end ha-ha view hewer of ‘narcissistic anger’ (as in Kohut), Goffman’s ‘facework’, Satir’s ‘levelling as cure—be direct yet respectful’ (see so-sociology’s gift for stating the bleeding obvious) as sounding brass stubbed out its silences in your face. Stinks brass bought, bone, aborted dearth, bore boundless. me. JW: Well I was very interested in this. I enjoyed the line of mockery, and indeed enjoyed the thought more generally that sociology is committed to ‘stating the bleeding obvious’. JG: It’s nothing personal! JW: It’s true, I’ve said it often enough! But then I was thinking: OK, so if the sociologist or the academic theorist of shame -the figure who’s interested in thinking about the social function of shame, as all these figures are (Freud, Durkheim, Elias, Sennett)- if they’re doing something that’s a bit bleeding obvious, as an academic you are nonetheless implicated in this discourse. It is clear that you’ve theorised shame at the same time as you’re writing poetically about it. I suppose I was trying to formulate a question in my mind along the lines of: if the shame-researcher is stating the bleeding obvious, what exactly is the poet doing? Both the sociologist and the poet are committed to coding, but perhaps to different ends? The Agency of Shame BS: At no point in this poem is there a statement ‘I am ashamed’, or a confession. That seems significant to me; in a sense, a discursive language of shame is trying to identify the thing it will never be, because the real time feeling of shame, so to speak, is not the same as an admission that you are ashamed. In fact to say ‘I am ashamed’ might be to displace shame? JG: I think the feeling of shame maybe has to do with an uncontrollable excess of emotion, so in some ways it is quite similar to sentimentality. I’m interested in language as excess and how the very act of writing involves something shameful, a letting go, a divulgence of something over which you then have no control. Not just in the normal sense that all writing’s outside your control once you let go of it, but as a shameless, orgiastic or extra-mental output. And this goes back to the linguistic side of it. If you read Jean Jacques Lecercle’s The Violence of Language, he speaks of a level of language which is superfluous to the meaning content of words and which will always find a way of erupting within any attempt to make language simply ‘mean’, to simply transmit information. I was reading that at the same time as writing the sequence and it ties in with Denise Riley’s essay ‘Is there Linguistic Guilt?’ Again, language is always shamefully in excess of what it’s meant to be talking about. And then the real shame comes in if I pretend that I actually have control over my words and my meanings. And here we go back to the kind of stiff-upper-lipedness and the class thing that I was talking about earlier and certainly the fantastically arrogant and egotistical notion that people are fully in control of their meanings all the time. This seems to me to lead to much more dangerous kinds of violence. I’m deeply suspicious of this puritan impulse to make language adhere to meaning; that it must mean what it says and say what it means. I see that as the real violence and the real shame. What does that lead you to? That leads you to euphemisms along the lines of ‘collateral damage’, ‘rectification of frontiers’; you know, all the kind of stuff that Orwell analysed back in the forties but which the media-sphere is full of now, with relation to Iraq or Afghanistan, or the micro-management of people in universities, and the denial and massaging of things that are happening to people in the health service, or in terms of unemployment, and so on, all of this kind of management-speak, as it were. That to me is the real violence of language and you get there because you deny the innate violence or play in language which should act as a sort of salutary reminder that you are not in control of meanings. You’re not totally in control of this coherent self, and you should think before you start pushing other people and words around as if they’re just mere counters in some sort of grand master plan that you’ve got. BS: Which relates to your not standing before your confessor saying, ‘I’ am an alibi for the experience? JG: It’s not that I’m trying to deny moral involvement or even culpability: it’s to say that this ‘I’ that speaks can’t be pinned down to everything that’s happening around it and within it. I’m not evading responsibility; on the contrary, I’m trying to own up to a fuller sort of responsibility through the granting of agency to language, and the investigation of the way that the self disintegrates and reforms, coheres and scatters in the process of trying to think through what it’s doing, what it’s narrating, and so on. And surely that is more ‘honest’ -if you want to use this romantic term- than pretending that you have direct access to yourself? Just as you don’t have direct access to other people, or the object world around you, so you’re never going to have direct access to yourself. You may trick your way into deeper knowledge of it; and here I think the model for me wouldn’t be confessionalism so much as something like Dada or Surrealism. You trick your way into a deeper knowledge of the ‘I’ and you attain insight in that way; but you cannot be totally in control of that process. Which means you can’t have a system that determines or can predict all the outputs. That has to be part of the risk of writing poetry. JW: I guess we’re now touching on the relationship between shame and knowledge. Many people writing on shame will insist that shame is the emotion of self-knowledge, but I think you’ve just helped us to think about how it can never be a stable mode of selfknowledge. If shame is anything to do with self-knowledge it won’t be a stable property, or a property that boasts adherence to something concrete. We’ve been asking the question: what is it to feel shame? I find it helpful to remind myself that shame never sits still; it never belongs and we can’t really be proprietorial about shame. I like to try and think about it as a rhythm, perhaps the rhythm of moving between exposing and then concealing. Therefore we can’t really work with the sentence ‘I am ashamed’ because that’s too final; it kind of betrays the mobility of shame somehow. JG: I think that’s absolutely right. ‘I am ashamed’ is a direct statement, isn’t it? It is positioning and stationing shame and pointing the ‘I’ towards it, and that is something that is very difficult to do for any length of time anyway. You can feel ashamed, but we’re talking about a transitive thing here, and a transitive thing you can’t actually have it in its place like that, it wriggles about on its backside because it’s embarrassed by its very nature; it refuses to sit still and it takes different forms. There may be a kind of overarching ontological sense of shame, in the human condition let’s say, or in the condition of modernity, but drawing on that and focussing it through a particular kind of perceived transgression is delightful at the same time. There are a couple of words in Italian which really charmed me when I came across them, one means crime [delitto] and the other means pleasure [diletto] and you get from one to the other by changing a single letter. I think this is something of what we’re talking about here; the oscillation of shame between those things. On Calling Yourself a Poet JW: I’d like to consider what institutions do to writing, and how shame operates in institutions that are invested -in all sorts of different ways- in the production of writing? I know that you teach creative writing, which is an area we’ve been looking at in our project. We’ve been doing some work with students of creative writing and asking them to think about how shame is formative in their writing practice. One of the questions we ask, and one I’d like to ask you, is, at what point did you call yourself a writer? BS: Or a poet? JG: Well I don’t know that I do even now… JW: OK… JG: And I say that because I’m in the institution. I’m in the Academy and I have to write critically and quite a lot of me is invested in that, although I don’t particularly like it. I’ve been doing a lot of it recently and maybe that’s one of the reasons why I’m saying it with quite this strength, but also I think my career as a writer is very gapped and partial and belated. When I compare my practice with that of other poets I know, I think they’ve committed to it, you know; they’ve taken a risk in terms of career; they’ve - I was going to use the word suffered - they’ve done badly in certain material worldly senses because of writing, and I haven’t. And by what right would I put on my passport, let’s say, ‘poet’? JW: OK, so that’s interesting then: you haven’t suffered enough to call yourself a writer? JG: I’m sorry I used the word suffering, and I really shouldn’t have done… JW: Why? JG: It puts it in a romantic frame and that maybe isn’t fully what I mean. I simply mean that there isn’t sufficient investment to be able to call mine a writerly career, completely. Although I think there is a development I can see through the last fifteen years of work. But whether you could call that the career of a poet, I’m not sure. And there would be a shame in claiming that title for me. JW: I’m wondering how that might play out with your teaching of creative writing to students. The first thing you learn on a creative writing course is that you’re to call yourself a writer even before you’ve been published. BS: Aren’t they being taught how to expose themselves as writers? JG: I think it’s to make themselves take what they’re doing seriously because the other thing they’re asked to do in the first class -and I haven’t taught that initial lesson myselfis keep a notebook. JW: Yeah. JG: ‘Don’t be embarrassed, this is just something you do because you’re a writer.’ I’m kind of in agreement with that; it’s self-empowering and they need to be told that at the beginning. But I don’t even keep a notebook, you know? Have you ever seen that Viz cartoon of pathetic sharks? They’re just pathetic sharks, they don’t bite anybody or kill anybody, they just play around and occasionally blow each other up by accident. I’m kind of like a pathetic poet in some ways. I’m an occasional poet, almost like a Sunday poet; it’ll hit me and sometimes I’ll do something or there’ll be a welling up of material as there is now and I’ve got to write something. But it’s all very slow. It’s a sort of long Kondratieff wave, a seventy year cycle to the world economy: I’m like that! I don’t get monthly or weekly impulsions to sit down and write, I know I should and I know I’d be a better writer if I did. There are so many dead poems, the things that I’ve thought of when I’ve walked across the park and then through habit or laziness, not written down, not developed, not pushed. You could fill a barrel with them, there are hundreds, there are thousands of them: so I don’t see myself as pushing hard enough to be able to call myself a poet. I’ll tag it on along with critic and translator. Even Dylan Thomas said this: when I’m in the bath eating Dolly Mixtures and reading the latest Agatha Christie, I’m not a poet. There is a sense in which a lot of poets these days, perhaps it comes out of Creative Writing, present themselves as the professional, full-time poet, and there’s something admirable about that, but I doubt whether it’s possible to keep it up with that intensity all the time, myself. Arriving at its Destination XLIX Timmy felt ashamed. Anne was rather ashamed of herself. Dick took her hands away and made her look at him. ‘Well, I did’, said Jo. ‘I’ve—I’ve squeezed through quite a lot of little windows. I know how to wriggle, you see.’ He thought her a bad, cold-blooded, savage little monkey, Jo loved a bit of kindness and couldn’t resist this. ‘She’s just crazy on Dick’, said Joan, taking up another saucepan. She looked at him as a slave might look at a king. ‘Red Tower isn’t a place. Red Tower is a man.’ How could Dick stand up for that awful girl? ‘I don’t know’, said Jo, who wasn’t quite certain what feeling ashamed meant. He felt as if he would dearly like to smack this unpredictable, annoying, extraordinary, yet somehow likeable ragamuffin girl. JG: There are two sonnets, you probably noticed, that came out of the same kind of register; they’re both cut-ups of Enid Blyton. This is always referring to its own practice: Cut-up’s corny’ is a line that keeps coming back throughout the poem. I think one of the characters in the Enid Blyton says ‘she loves Dick’? JW: ‘She’s just crazy on Dick’. JG: ‘She’s just crazy on Dick’. Shameful, isn’t it? Just to go back to what you were saying about things being concealed and obvious at the same time, this is something I often get from Dylan Thomas. There’s a poem called, ‘When once the waters of your face’: ‘When once the waters of your face spun to my screws…’ and you know, in that line and a half, ‘spun to my screws’ means ‘did my bidding’, I think, and the image is of a ship out there in the bay, propellers driving it along. But ‘screws’ is also meant in the American sense of sexual intercourse, isn’t it? And what he’s saying is like ‘The Purloined Letter’, and what Lacan does with that: it’s so obvious that I know you won’t get it, I’m placing it where I know you will see it and miss it at the same time. I’m pretty sure that most of the things which are in the poem which might actually point to the identity of the people who are involved, you know, and particularly the main addressee, won’t be picked up on by readers. I know they won’t. In other words, what I’m saying is that I’ve put things in the poem which I know readers won’t get, and there’s a kind of shamefulness in that too. But they have to be in there to satisfy me because at some level this has to be a direct address, even if the addressee herself doesn’t ever notice it. So it’s a bit like Thomas’s use of the ‘screws’. It’s there, but you know, I know, it won’t be found. Illennium by John Goodby can be ordered here: http://www.shearsman.com/pages/books/catalog/2010/goodby.html