Implications for regulation: lessons from Biopesticides Dr Justin Greaves, University of Warwick

advertisement

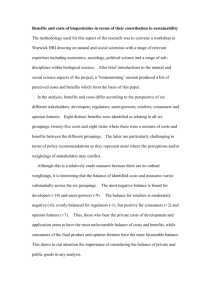

Implications for regulation: lessons from Biopesticides Dr Justin Greaves, University of Warwick • This presentation is based on an article of mine in Public Policy and Administration, Volume 24, no 3, 2009 • The research project upon which this article draws is funded by the Rural Economy and Land Use Programme Introduction • Bureaucrats and regulators are typically (and understandably) risk averse • Their desire to avoid things going wrong means they are not natural innovators • Risk averseness does not create an encouraging environment for regulatory innovation – term almost a contradiction Pesticides Safety Directorate (PSD) • We use the example of PSD’s work on biopesticides to examine and develop accounts of regulatory innovation • PSD was an agency of the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) • Around 200 staff – responsible for the registration of agricultural pesticides Important to note ... • The Chemical Regulation Directorate has now been created in the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) • Formed in April 2009 this integrates PSD with responsibility for biocides What are biopesticides? • Biopesticides are mass produced biologically based agents used for the control of plant pests. They include: - Living Organisms (natural enemies) invertebrates, nematodes and micro-organisms - Naturally Occurring substances plant abstracts; Semiochemicals (eg: insect pheromones) - Genes (USA) Plant Incorporated Products Why such a low take-up? • Microbial biopesticides represent less than 1% of the global market • One explanation is ‘market failure’ – the market is too small to provide economies of scale and encourage firms to enter • The other explanation is that of ‘regulatory failure’ Bureucratic theory • Systems of regulation may have unintended consequences • Bureaucratic theory points to a tendency for mechanisms to replace goals, for processes to become more important than outcomes • UK regulatory system developed according to a chemical pesticide model a barrier to biopesticide commercialisation What is regulatory innovation? • Distinction between change and innovation • Innovation can be seen as ‘the application of new solutions to old problems, or new solutions to new (or newly constructed) problems, but not old solutions to old problems (Black 2005) What is regulatory innovation? (2) • Hall’s typology of policy change 1.1st order changes are changes to the levels or settings of basic instruments (not considered here innovation) 2.2nd order changes are changes in technique, process or instrument 3.3rd order changes involve changes in the goals and understandings of policy (‘paradigm shifts’) Policy networks • Policy network theory suggests networks good at managing incremental change • Only tend to innovate in conditions of crisis or exogenous shock • Situation complicated by an underperforming and incomplete policy network (see Greaves and Grant article in British Politics, 2010, vol 5, no 1) How and why does regulatory innovation occur? • Black’s five worlds of regulatory innovation 1.The individual 2.The organization 3.The state 4.The global polity 5.‘the world of the innovation’ Criticism of Black • Academia criticized for lack of high quality research on innovation in public sector – ‘how was it done’ • Black’s ‘five worlds’ do not lend themselves to practice, often no identifiable tools for action • Trying to cover every possible theory or explanation – potentially little leverage Warwick iCast • Before we continue here is a short video clip on the project, bringing out some of the issues we are discussing The Biopesticides Scheme • In June 2003 PSD launched a pilot scheme to promote alternative control measures • Reduced registration fees, pre-submission meetings. • A permanent Biopesticides Scheme launched in June 2006 – also introducing the role of a Biopesticides ‘champion’ Other changes • Change of ‘culture’ just as important • An ‘internal reorientation’ • Pragmatism and rules ‘open to interpretation’ • Use of published data rather than expensive field trials where appropriate • An acknowledgment different questions may need to be asked about biologicals But is this innovation? • Reduction in fees 1st order policy change • Much is 2nd order – pre-submission meetings, biopesticides champion etc • Change in ‘paradigm’? (Buffin) • Unusual for a regulatory agency to negotiate new policy spaces it which to operate • ‘Quite remarkable for a regulatory agency’ Contextual drivers • The public are concerned about the possible health effects of pesticide residues on food • This leads to action by retailers and others • Environmental concerns • The problem of ‘resistance’ Exogenous pressures • Defra was keen to encourage the wider use of biopesticides • Given slow progress, the institutions of the core executive needed to intervene • The Business Regulation Team (BRT) of the Cabinet Office ‘leaned’ on PSD • ‘Aims and Objectives’ agreed with ministers in Spring 2003 included developing and introducing alternatives Endogenous pressures • There was also an endogenous steer from within PSD • They were keen to discuss how the new aim could be promoted • Key individuals important in driving through innovation • ‘Horizontal’ working practices Endogenous pressures (2) • Those who work on biopesticides have shown great enthusiasm for their work • Desire to do a ‘better job’, career building etc • They see themselves as scientists first and regulators second • This results in a desire to learn, driving innovation forward A ‘champion’ organization • The literature refers to ‘champions’ who push through innovation • But a gap in the literature when it comes to ‘champion organizations’ • Could a quasi-governmental organization, an advocate of biopesticides, lead to greater regulatory change? • Consider BPPD of the EPA in US Reform of institutional structures • Hampton Review on regulation reported in April 2005 • Proposed streamlining – too many small regulators • Implication PSD should be merged into a larger thematic regulator • But could a smaller organisation be more flexible and responsive? • Could the initiative on biopesticides end up being lost? Conclusions and lessons (1) • Fundamental tension between expectations that regulators will be consistent, predictable and impartial – yet also innovative • Consequences of making a mistake are serious, esp where public/environmental safety concerned • But regulators must respond to changing demands in society and retain trust of politicians and stakeholders Conclusions and lessons (2) • In terms of animal health issues 1.Are there any lessons for the proposed Animal Health Organization? 2.Should the regulation of plant and animal diseases be in separate compartments? Please visit our website : http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/bi opesticides Acknowledgements: Prof Wyn Grant Prof Mark Tatchell Dr David Chandler Gillian Prince (University of Warwick)