DOING THE RIGHT THING

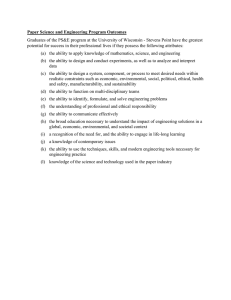

advertisement