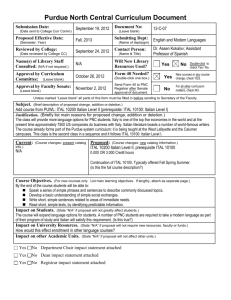

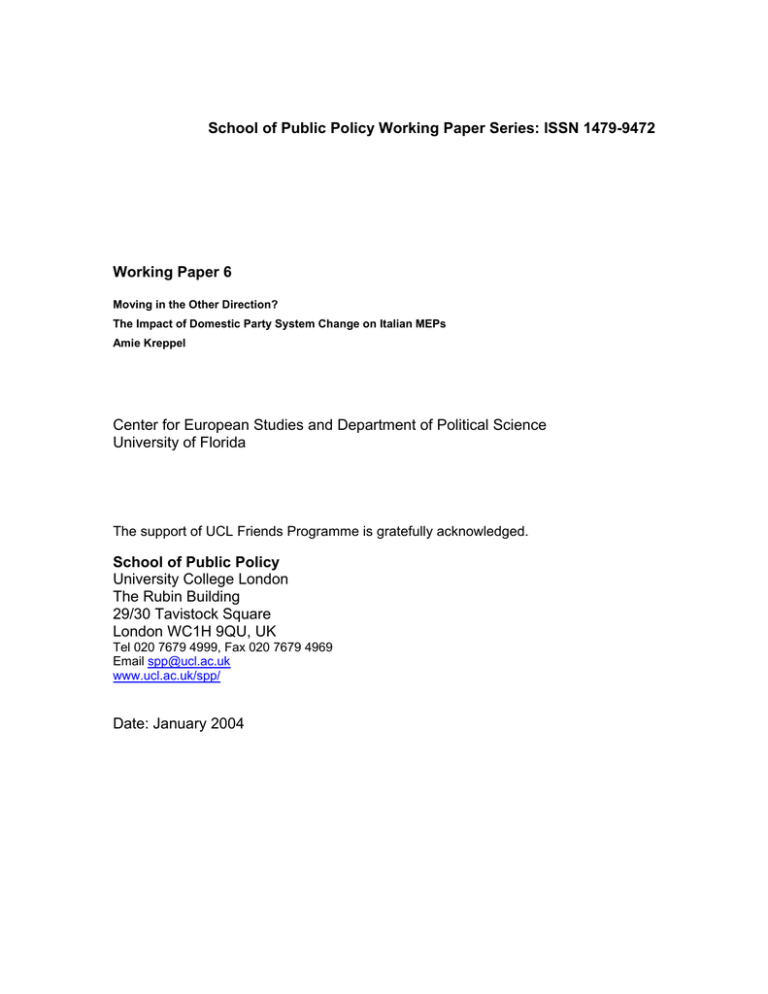

School of Public Policy Working Paper Series: ISSN 1479-9472

advertisement