Document 12333913

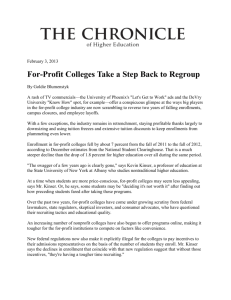

advertisement