Complex Effects of Ecosystem Engineer ... Ecosystem Response to Detrital Macroalgae

advertisement

OPEN

3 ACCESS Freely available online

<P PLOS Io h .

Complex Effects of Ecosystem Engineer Loss on Benthic

Ecosystem Response to Detrital Macroalgae

Francesca Rossi1*, Britta Gribsholt2, Frederic Gazeau3'4, Valentina Di Santo5, Jack J. M iddelburg2'6

1 Laboratoire Ecologie des Systèmes marins côtiers, Université Montpellier 2, Montpellier, France, 2 D epartm ent of Ecosystems, Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea

Research, Yerseke, th e Netherlands, 3 Centre National d e la Recherche Scientifique-lnstitut National des Sciences d e l'Univers, Laboratoire d' O céanographie d e

Villefranche, Villefranche-sur-mer, France, 4 Université Pierre e t Marie Curie, Observatoire O céanologique de Villefranche, Villefranche-sur-mer, France, 5 D epartm ent of

Biology, Boston University, Boston, M assachusetts, United States o f America, 6 D epartm ent of Earth Sciences - Geochemistry, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University,

Utrecht, The Netherlands

Abstract

Ecosystem e n g in e e r s c h a n g e a bio tic c on ditio ns, c o m m u n i ty a s s e m b ly a n d e c o s y s t e m function ing. C o n se q u e n tly , their loss

m ay modify t h r e s h o ld s o f e c o s y s t e m r e s p o n s e t o d i s t u r b a n c e a n d u n d e r m i n e e c o s y s t e m stability. This s t u d y in vestiga te s

h o w loss o f t h e b i o tu r b a tin g l u g w o rm Arenicola m arina modifies t h e r e s p o n s e to m acroalgal detrital e n r ic h m e n t o f

s e d i m e n t b io g e o c h e m ic a l propert ies, m i c r o p h y t o b e n t h o s a n d m a c r o fa u n a a s s e m b la g e s . A field m anip u lativ e e x p e r i m e n t

w a s d o n e o n an intertidal sa nd flat (O o s te rsc h eld e estuary, The Netherlands). L u g w o rm s w e r e de libe ra tely e x c lu d e d from

1 X m s e d i m e n t plots a n d different a m o u n t s o f detrital Ulva (0, 200 o r 600 g W et Weight) w e re a d d e d twice. S e d im e n t

b i o g e o c h e m is tr y c h a n g e s w e re e v a lu a te d t h r o u g h b e n th i c respiration, s e d i m e n t o rg a n ic c a r b o n c o n t e n t a n d p o r e w a t e r

inorganic c a r b o n as well as de trital m a c r o a lg a e re m a in ing in t h e s e d i m e n t o n e m o n t h a fte r e n r ic h m e n t. Microalgal b io m a ss

a n d m a c r o fa u n a c o m p o s it i o n w e r e m e a s u r e d at t h e s a m e tim e. Macroalgal c a r b o n m ineralization a n d tran sfer t o t h e

b e n th i c c o n s u m e r s w e r e also in v e s tig a te d d u rin g d e c o m p o s i t io n a t low e n r i c h m e n t level (200 g WW). T he interaction

b e t w e e n lu g w o r m exclusion a n d detrital e n r ic h m e n t did n o t m odify s e d i m e n t o rg a n ic c a r b o n o r b e n th i c respiration. W eak

b u t significant c h a n g e s w e r e in stea d fo u n d for p o r e w a t e r inorg an ic c a r b o n a n d m icroalgal biom ass. L ug w o rm exclusion

c a u s e d a n increase o f p o r e w a t e r c a r b o n a n d a d e c r e a s e o f microalgal biom ass, while detrital e n r i c h m e n t d ro v e t h e s e values

b a ck t o values typical o f lu g w o r m - d o m i n a te d se d im e n ts. L u g w o rm exclusion also d e c r e a s e d t h e a m o u n t of m a c r o a lg a e

re m a in ing into t h e s e d i m e n t a n d a c c e le ra te d detrital c a r b o n m ineralization a n d C 0 2 release t o t h e w a t e r c o lu m n .

Eventually, t h e interactio n b e t w e e n l u g w o rm exclusion a n d detrital e n r i c h m e n t a ffected m a c r o f a u n a a b u n d a n c e a n d

diversity, which c olla p sed a t high level o f e n r ic h m e n t only w h e n t h e lu g w o r m s w e re p re sen t. This s t u d y reveals t h a t in

n a tu re t h e role of this e c o s y s t e m e n g i n e e r m ay b e variable a n d s o m e t i m e s have no o r e v e n n e g a tiv e effects o n stability,

c on versely t o w h a t it s h o u ld b e e x p e c t e d b a se d o n c u rre n t research kn o w le d g e.

C itation : Rossi F, Gribsholt B, Gazeau F, Di Santo V, Middelburg JJ (2013) Complex Effects of Ecosystem Engineer Loss on Benthic Ecosystem Response to Detrital

Macroalgae. PLoS ONE 8(6): e66650. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066650

Editor: Andrew Davies, Bangor University, United Kingdom

Received Septem ber 25, 2012; A ccepted May 10, 2013; Published June 21, 2013

C opyrigh t: © 2013 Rossi e t al. This is an open-access article distributed under th e term s of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided th e original author and source are credited.

Funding: This work was funded by a PIONIER grant o f th e Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research to JJM. The funders had no role in study design, data

analysis, decision to publish, or preparation o f th e manuscript.

C om peting Interests: The authors have declared th a t no com peting interest exist.

* E-mail: francesca.rossi@univ-montp2

Introduction

response to disturbances [10-12]. O n e or few species can be key

contributors to ecosystem functions to the extent th a t their loss can

outw eigh the effect o f species richness o n ecosystem functions,

resilience o r resistance [10,13,14], Such overw helm ing effect can,

how ever, vary w ith the e nvironm ental context a n d change w ith

increasing ecological com plexity [15]. It seems thus evident th at

un d erstan d in g the role o f species loss in m arin e systems m ight

req u ire a large body o f know ledge o f the functional role o f

individual species a n d o f the consequences o f losing particu lar

species for ecosystem functions a n d for their response to

disturbance.

Ecosystem engineer species strongly m odify resource availability

a n d en v ironm ental conditions, w hich in tu rn can alter c o m m u ­

nities a n d ecosystem functions [16,17]. T hese species are thus ideal

candidates to test hypotheses o n how local extinction o f key

contributors to ecosystem functions can m odulate the response o f

ecosystem s to disturbance. In m arin e sedim ents a n d terrestrial

soils, ecosystem engineers are often species th a t c ontribute to

It is w idely recognized th a t species loss m ay affect ecosystem

stability and, in tu rn , have im p o rta n t social a n d ecological

consequences [1—3]. O verall, w hen m ore species are presen t in a

com m unity, ecosystem functions are m ore stable in tim e a n d

increase their resistance o r resilience against disturbance, due to

a n increased variety o f life strategies, functional traits a n d

responses to e nvironm ental d isturbance [4—6], D ifferent species

con trib u tin g to sim ilar ecosystem functions can occur u n d e r

different e nvironm ental conditions a n d ensure th a t functions are

p erfo rm ed even w h en som e o th er species are displaced [4,5,7].

E m pirical evidence has show n th a t som etim es species loss can

have com plex, often idiosyncratic effects on the stability o f

ecosystem functions a n d o n b o th th eir resistance a n d resilience

against d isturbance [8,9], T his is especially tru e for the m arine

coastal ecosystem , w here species identity, functional traits a n d

e nvironm ental con text m ay rule ecosystem functions a n d their

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

1

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects o f Ecosystem Engineer Loss

o f lugw orm s w ould increase the m agnitude o f changes caused by

the d isturbance o f m acroalgal detritus for (i) carb o n availability

a n d b enthic respiration; (ii) m icroalgal biom ass a n d (iii) m acrofauna assem blages. R ecycling o f the organic carb o n derived from

detrital decom position was also investigated to explore som e o f the

m echanism s th a t m ight regulate the effect o f el. marina o n benthic

responses to m acroalgal detritus.

particle m ixing a n d solute p e n etratio n into the sedim ent th ro u g h

the process o f b io tu rb atio n , w hich includes sedim ent rew orking

a n d b u rro w ventilation [18], T hese b io tu rb a tin g engineer species

can be g reat contributors to diagenetic reactions, to the recycling

o f sedim entary organic m atter, a n d to benthic com m unity

structure a n d biodiversity [18-21]. T h ey also have the p otential

to strongly m odify the response to d isturbance o f benthic

com m unities a n d functions [22]. F or instance b io tu rb a tio n by

Marenzellaria viridis has b e en found to decrease hypoxic crises in the

Baltic Sea [23]. It has also b e en found th a t in soil, rew orking

activity o f d o m in a n t c o ntributors to b io tu rb atio n , such as

earthw orm s, m odulates the response o f p lan t com m unities to

invasions [24]. Surprisingly, how ever, ecosystem engineer loss has

b e en poorly considered in studies investigating ecosystem response

to disturbance.

In m arin e coastal systems, a large p o rtio n o f seaweeds a n d

seagrasses is n o t consum ed by herbivores b u t retu rn s to the

env iro n m en t as decaying organic m a tte r [25]. In shallow -w ater

coastal habitats, d etrital seaweeds a n d seagrasses can supply

im p o rta n t am ounts o f organic m a tte r to b enthic ecosystem s. T h ey

represent a n im p o rta n t source o f d isturbance because du rin g

decom position they can alter sedim ent biogeochem istry and, in

tu rn , b enthic com m unities o f consum ers. D espite detrital seaw eed

a n d seagrass supply is often a n a tu ra l event, proliferation a n d

bloom s o f seaweeds as a consequence o f e u tro p h icatio n can

dram atically increase detrital seaw eed biom ass a n d exacerbate the

effects on benthic ecosystem s [26-29]. Biom ass decom position can

induce hypoxia follow ed b y the release o f red u ced toxic

com pounds such as sulphides, w hich are toxic for several benthic

species a n d can therefore strongly reduce species a b u n d an c e a n d

diversity [26,27,29-33]. D etrital decom position can also provide

food, directly for detritivores o r indirectly, b y stim ulating bacterial

m etabolism , thereby altering the b enthic food w eb [28,34]. T hese

effects strongly d e p en d o n the a m o u n t o f d etrital inputs a n d o n its

decom position p atterns, w hich m ay strongly v ary as a conse­

quence o f b enthic invertebrate com position a n d identity [35].

B ioturbating fauna can m odulate the recycling o f detrital

m acroalgae en h an c in g organic m atter m ineralization a n d m icro­

bial activity [36-38]. Som e b u rro w in g b io tu rb a tin g species, such

as certain crabs o r polychaetes, can also in co rp o ra te detritus into

th eir b u rro w wall lining a n d represent im p o rta n t sinks for detrital

m acroalgae [39]. In addition, often b io tu rb a tin g infauna are also

detritivores th a t c an consum e directly detritus a n d c o n trib u te to its

recycling in the food w eb. In a lab o rato ry experim ent, for instance,

it was found th a t nitro g en a n d c arb o n fluxes at the sedim ent-w ater

interface ch an g ed following b o th the addition o f the d etrital green

m acroalgae Chaetomorpha linum a n d the presence o f the b io tu rb a tin g

polychaete Nereis diversicolor. T his polychaete ingested m acroalgal

fragm ents, e n h an c ed m icrobial m etabolism a n d co n trib u ted to

diffuse solutes in the interstitial sedim ent a n d at the sedim entw ater interface [36],

O n e co m m o n w ell-recognized b io tu rb a tin g species typical o f

tem p erate w aters is the bu rro w in g lugw orm Arenicola marina. T his

w orm lives h e a d dow n in J-sh a p e d burrow s w here it ingests

sedim ent a n d defecates o n the surface. Its activity has been

recognized to destabilize sedim ent a n d co u n te rac t the effect o f

m icrophytobenthos, increase sedim ent m icrohabitats a n d alter

sedim ent biogeochem istry, b y e n h an cin g solute p e n etratio n into

sedim ent d e p th a n d re-distributing organic m aterial along the

vertical profile [40], C onsequently, this species m ay alter o th er

fau n a a n d vegetation [36,37,41], T his study reports o n how the

loss o f this b io tu rb a tin g lugw orm m ay alter the response to detrital

m acroalgae o f intertidal benthic m acro fau n a a n d sedim ent

biogeochem istry. It was hypothesized th a t the deliberate exclusion

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

M aterials and Methods

S tu d y Site a n d E x p e rim e n ta l D esig n

T w o m anipulative experim ents w ere done o n a n intertidal flat

o f the O osterschelde estuary (T he N etherlands) d o m in a ted by the

b io tu rb a tin g lugw orm Arenicola marina, du rin g sum m er 2006. T h e

study intertidal flat, n a m e d Slikken van V iane (51" 3 7 ' 0 0 " N , 4"

0 1 ' 0 0 " E), was a sheltered a re a situated on the u p p e r intertidal

close to a salt m arsh. S edim ent grain-size was 65% fine sand a n d

35% very fine sand (Rossi F., u n p ublished data). T h e O os­

terschelde estuary is a natio n al p a rk designated as zone V I by the

In tern a tio n a l U n io n for C onservation o f N a tu re (IU CN ). T his

IU C N classification has a m o n g its objectives the facilitation o f

scientific research a n d e nvironm ental m onitoring, m ainly related

to the conservation a n d sustainable use o f n a tu ra l resources

(h ttp ://w w w .iu c n .o rg ). N o specific perm its w ere therefore re ­

q u ired for p erfo rm in g these scientific experim ents, w hich did not

involve en d an g e red o r p ro tec te d species. T h e first experim ent

tested the effect o f el. marina exclusion o n the response o f

m acro fau n a assem blages a n d sedim ent biogeochem istry to differ­

ent am ounts o f d etrital m acroalgae. T h e second experim ent

m easured the changes in detrital recycling follow ing el. marina

exclusion. F or the first ex p erim ent (Fig. 1), all lugw orm s w ere

excluded from 15 ran d o m ly chosen sedim ent plots o f l x l m,

som e m eters ap art, by bu ry in g m osquito nets to the d e p th o f

approxim ately 7 cm (hereafter exclusion A — treatm ent), following

the m eth o d p ro p o sed by [41] in a m ore extensive area. A

p ro c ed u ra l control for the effect o f the n et a n d o f the b u rial was

done for o th er 15 sedim ent plots o f 1 x i m by bu ry in g m osquito

nets w ith 1 0 x 1 0 cm holes (hereafter p ro c ed u ra l control A +

treatm ent).

O n e m o n th after lugw orm exclusion, the sedim ent plots w ere

organically-enriched b y ad dition o f d etrital Ulva spp. Fresh Ulva

thalli w ere previously collected in the O osterschelde estuary a n d

w ashed to rem ove anim als a n d sedim ent. T halli w ere th en

w eighted a n d frozen in separate plastic bags. F reezing is

■ L ugw orm excluded plots (A -)

□ Procedural control plots (A + )

600

0

200 600

0

200

200

0

600 600

0

200

0

200

0

200 600

0

600

0

200 600 600

0

200 600

600 200

0

200

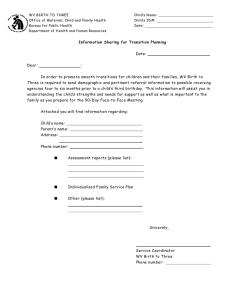

Figure 1. Schematic experim ental design fo r ex p erim ent 1. Each

rectangle co rre sp o n d s to 1 m 2 plot. N um bers refers to th e detrital

enrichm ent. (0: no addition; 200:200 g WW w ere a d d ed tw ice a t a 1

w eek interval; 600:600 g WW w ere ad d e d tw ice with a 1 w eek interval).

D istance am o n g plots are n o t in scale.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066650.g001

2

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects of Ecosystem Engineer Loss

3 111111 in n er diam eter (i.d.). F o r chlorophyll a, the sedim ent was

collected to 1 cm depth, kept in the d ark a n d preserved at —80°C.

T h e sedim ent for O C was collected to the d ep th o f 6 cm,

sectioned into 0- 1, 1-2 a n d 2 -6 cm depths a n d preserved freezedried. Ulva detritus was rem oved from this sedim ent u n d e r the

stereo-m icroscope. T h e sedim ent for p o re w ate r D IC extraction

was collected w ith cores o f 5 cm i.d. a n d sectioned into 0 -1 , 1-2

a n d 2 -6 cm d epth intervals at the lowest a n d highest levels o f

organic en rich m en t (0 a n d 600) in b o th the control a n d the

exclusion treatm ents. T w o cores w ere collected from each plot a n d

th en pooled to reach the a m o u n t o f w a ter need ed for the analyses.

P orew ater was extracted by centrifugation (1344 g, 15 m in) a n d

the su p e rn ata n t was filtered on M illipore 45 |Im . T h e extracted

w ater was stored in glass vials, sealed, im m ediately poisoned w ith

satu rated H g C F to stop bacterial activity a n d analyzed w ithin 3 d.

O nly 3 out o f 5 random ly-chosen replicate plots w ere sam pled for

O C an d T C O 2.

T h e sedim ent for m acro fau n a was collected using 11 cm i.d.

PV C core. T h is sedim ent was sieved (0.5 n in i m esh) a n d

m acro fau n a fixed in 4% buffered form ol. Before sam pling, all

plots w ere p h o to g rap h e d to estim ate the ab u n d an c e o f A. marina

using visible m ounds. In the laboratory, all plots w ere in d ep e n ­

dently exam ined by four researchers to reduce estim ate bias. Five

random ly-chosen n a tu ra l plots w ere also p h o to g rap h e d a n d th en

sam pled using 11 cm i.d. cores to test for the effect o f the

p ro c ed u ra l control A + on the n a tu ra l a b u n d an c e o f A. marina a n d

o f the o th er benthic m acrofauna. N o differences w ere detected

betw een n a tu ra l a n d p ro c ed u ra l control treatm en ts (see Results

section) a n d this latter was used for evaluating the effect o f detrital

en rich m en t an d lugw orm exclusion.

S edim ent cores w ere also used to m easure fluxes o f inorganic

c arb o n (TCCF) a n d oxygen (CF) at the sedim ent-w ater interface.

In tac t sedim ent cores w ere collected by p ushing Plexiglas cores

(11 cm i.d.) into the sedim ent to a d e p th o f 20 cm at each o f th ree

replicate plots for the lowest a n d the highest levels o f organic

en rich m en t (0 an d 600) in b o th the control a n d the exclusion

treatm ents. T h e n e t w as carefully cut a ro u n d the cores to allow the

core p e n etratio n into the sedim ent. C ores w ere sealed w ith ru b b e r

stoppers a n d d ug out o f the sedim ent. All cores w ere b ro u g h t to a

clim ate controlled ro o m w ithin 2 h, a n d kept in the d ark at in situ

tem p e ra tu re (10°C) before fu rth er handling. T h e sam e day, the

cores w ere in cu b ated in the d ark for 12 h. In c u b atio n in the dark

com m only used in experim ents th a t aim s at testing effects o f

detrital m acroalgae a n d decom position patterns. T his trea tm e n t is

necessary in o rd e r to create detritus a n d ensure th a t Ulva is d ead

w hen bu ried since this seaw eed can survive for very long periods in

the d ark [30]. T h e thalli w ere left defrosting a t air tem p e ra tu re

an d th en ad d ed to the top 1 cm o f the sedim ent by gently h andch u rn in g the detritus w ith the sedim ent. E n ric h m en t was done

twice, on Ju ly 3 a n d Ju ly 10, 2006. E ach tim e either 200 o r 600 g

o f w et w eighted Ulva (hereafter treatm en ts 200 a n d 600,

respectively) w ere ad d ed to 10 exclusion (A —) a n d 10 pro ced u ral

control (A—) plots. T hese am ounts corresponded to 40 a n d 120 g

dry weight. O th e r 10 plots (5 A — a n d 5 A+) w ere n o t enriched

(hereafter trea tm e n t 0), b u t the sedim ent was h a n d -ch u rn e d to

control for the m anipulation. T h e re was no p ro c ed u ra l control for

the physical presence o f detritus as previous experim ents h a d

dem o n strated no effects [28-30]. T h e a m o u n t o f Ulva spp. was

based on the available literature to cause m ed iu m a n d high levels

o f disturbance (e.g. [27,30,32,33]).

T h e second ex p erim ent was ru n at the sam e tim e o f experim ent

1. T w o additional p ro c ed u ra l control plots for b urial a n d 2

exclusion plots w ere enrich ed w ith 200 g loC -labelled Ulva twice,

resem bling the tre a tm e n t “ 2 00” . T hese four plots w ere used to

trace the fate o f the carb o n released from detrital Ulva. T h e

labeling o f Ulva was done in the laboratory. Leaves w ere w ashed

an d carefully cleaned to elim inate epiphytes a n d anim als. T h en ,

thalli w ere transferred to a q u aria c o ntaining filtered seaw ater

supplem ented w ith N a H loC 0 3 (99% loC) to the con cen tratio n of

0.2 g L \ T h e a q u aria w ere oxygenated a n d covered w ith

tran sp are n t PV C to lim it 1 'C b acterial respiration.

Field S a m p l in g

F o r the first experim ent, sam pling was done on Ju ly 30 a n d

A ugust 1, 2006, one m o n th after detrital enrichm ent. T his tim ing

was chosen because previous studies suggested th a t effects o f algal

m ats on m acro fau n a occur w ithin 2 to 10 weeks from the

deposition [31-33,42] a n d th a t decom position o f Ulva occurs

w ithin a m o n th (e.g. [43,44]).

S edim ent sam ples w ere taken for organic c arb o n (hereafter

O C ), p o re w ate r total inorganic c arb o n (D IC —H 2C O 3+

H C O 3 + C O 32 ), m icroalgal biom ass (chlorophyll a) a n d m ac ro ­

fauna species com position, a b u n d an c e a n d diversity. T h e sedim ent

for chlorophyll a a n d O C was collected using a cut syringe of

Arenicola-Qxeluded sediment

Procedural control sediment

(A-)

(A+)

Figure 2. Comparison o f sedim ent surface appearance a fte r Arenicola m arina exclusion a t low tid e . A - rep resen t th e sed im en t after 1

m o n th from th e burial of net to exclude burrow ing species. A+ is th e procedural control tre a tm e n t (see Materials and M ethods for details).

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066650.g002

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

3

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects o f Ecosystem Engineer Loss

□ 0

■ 200

■ 600

Table 1. T w o-w ay analyses o f variance for s e d i m e n t o rga nic

c a r b o n (OC) a n d p o r e w a t e r DIC a t different s e d i m e n t d e p t h s

o n e m o n t h a fte r detrital e n r ic h m e n t.

01 cm

A+

lcm

A-

A+

A-

2 cm

A+

6 cm

(b)

26 cm

1 -2 cm

S edim ent OC

d f MS

F

MS

F

MS

F

Exclusion = E

1 0.67

10-3

0.40

1.60 10~3

3.80

0.09

10-3

0.52

Detrital

enrichm ent = D

2 0.61

10-3

0.96

0.09 10~3

0.40

0.62

10-3

2.22

ExD

2

1.7 10 " 32.64

0.42 10~3

1.90

0.17

10-3

0.62

Residual

12 0.63

10-3

0.22 10~3

0.28

10-3

P orew ater DIC

y

1

Id Id i

A+

lcm

A+

2 cm

A-

1 1.89

17.50 5.06

1.03

10.15

4.80

Detrital

enrichm ent = D

1 0.06

2.00

1.28

5.12

0.15

0.28

ExD

1 0.11

3.43

4.93

19.71

0.30

0.57*

Residual

8 0.03

1.00

2.11

A+

Significant values (P<0.05) are n bold. Data were not-transformed (PC-cochran

>0.05). Asterisk indicates pooling of interaction w hen P>0.25.

6 cm

Figure 3. M ean (+1SE) fo r (a) b u lk sedim ent organic carbon

(OC) and (b) p orew ater dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) at

d iffe re n t sedim ent depths { I c m surface sedim ent to 1 cm

d epth; 2 cm. from th e d ep th o f 1 to 2 cm; 6 cm: from the d ep th

o f 2 to 6 cm). In th e g raphs, A—: A. marina excluded; A+: procedural

control for burial; th e legend indicate th e levels o f detrital addition (0:

no addition; 200:200 g WW w ere ad d e d tw ice a t a 1 w eek interval;

600:600 g WW w ere ad d e d tw ice with a 1 w eek interval). Data w ere

sam pled o n e m o n th after detrital addition. Asterisk indicates significant

differences.

doi:10.1371/jo u rn al.pone.0066650.g003

(a)

150.00

•3

100.00

P

50.00

0.00

did n o t allow to g ath er ad ditional inform ation con cern in g the

(auto)trophic state o f the sedim ent, w hich w ould need a light

incubations o f o th er sedim ent cores. O u r system was how ever

lim ited to carry 12 cores a t a tim e a n d no fu rth er analyses could b e

done. P rio r to incubations, cores w ere in u n d ate d w ith welloxygenated O osterschelde w ater collected the sam e day

([N H 4+] = 20 pm o l L", [ N 0 3~] = 110 pm o l L “ 1, salinity = 22)

a n d left to acclim atize in the d ark for 6 -8 h. D u rin g incubation,

the overlying w ater-colum n (25-30 cm) was continuously stirred

w ith a m agnetic stirrer, m ain tain in g continuous w ater circulation

at a ra te well below the resuspension lim it. Dissolved 0 2 never

decreased below 65% o f saturation. W ater sam ples for T C 0 2 a n d

0 2 w ere collected in glass vials a n d sealed avoiding a ir bubbles. All

sam ples w ere im m ediately poisoned w ith satu rated H g C l2 to stop

b acterial activity a n d th en analyzed w ithin 3 d.

F o r ex p erim ent 2, sedim ent sam ples w ere taken from the four

plots w ith labelled Ulva. Sam pling was done on four occasions, 6 ,

8, 15 a n d 17 days after d etrital enrichm ent. E ach tim e, one

plexiglass intact sedim ent core (11 cm i.d.) was collected to 20 cm

d epth, follow ing the m odality used to sam ple the cores for

estim ating b enthic respiration. T o reduce plot dam age d u rin g core

collection, the central p a rt o f the plot (20 cm from the edges) was

divided into 4 q u a d ran ts o f 3 0 x 3 0 cm . E ach sam pling occasion, a

sedim ent core was taken from a different q u a d ran t. A n a rea o f

1 5 x 1 5 cm was thus dam ages each tim e, correspondin g to 2.25%

o f the entire plot area. T h e sam pled sedim ent was replaced w ith

plexiglass tubes to avoid any collapse a n d to leave the rem ain in g

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

Exclusion = E

ΠI

-50.00

o<1

-

100.00

A-

(b)

A+

2.5

1.5

0.5

A-

A+

Figure 4. M ean (+1 SE) fo r (a) benthic oxygen ( 0 2) consum ption

and total carbon d io x id e (T C 0 2) released d uring 12 hours d ark

incubation; (b) Respiratory q u o tie n t (RQ). In th e graphs, A : A.

marina excluded; A+: procedural control for burial; th e leg en d indicate

th e levels of detrital addition (0: no addition; 200:200 g WW w ere ad d ed

tw ice a t a 1 w eek interval; 600:600 g WW w ere ad d e d tw ice w ith a

1 w eek interval). Data w ere sam pled o n e m o n th after detrital addition.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066650.g004

4

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects o f Ecosystem Engineer Loss

Table 2. T w o-w ay analyses o f variance for s e d i m e n t - w a t e r

e x c h a n g e s of 0 2 a n d T C 0 2 a n d for t h e b e n th ic respiratory

coefficient RQ.

tc o 2

o2

d f MS

F

F

MS

F

Exclusion = E

1 8.8 10-6 2.38

252.08

0.78

0.29

2.39

Detrital

enrichm ent = D

1 8.0 10-9 0.00

102.08

0.31

0.02

0.18

0.22*

0.00

0.01*

1 4.38 1 ~7 0.11* 70.08

Residual

8 4.10 1-6

325.08

m

M)

0

[

D 200

■ 600

25

RQ

MS

ExD

30

A-

A+

0.14

Figure 5. M ean (+1SE) fo r chlorophyll a concentration a t the

surface sedim ent (1 cm d ep th ). In th e graphs, A - : A. marina

excluded; A+: procedural control for burial; th e legend indicate th e

levels of detrital addition (0: no addition; 200:200 g WW w ere ad d ed

tw ice a t a 1 w eek interval; 600:600 g WW w ere ad d e d tw ice w ith a 1

w eek interval). Data w ere sam pled o n e m o n th after detrital addition.

Asterisk indicates significant differences.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066650.g005

Significant values (P<0.05) are in bold. Data w ere not-transformed (Pc-cochran

>0.05), except for O2, which was arc-tangent transform ed to hom ogenise the

residual variances. Asterisk indicates pooling o f interaction w hen P>0.25.

doi:10.1371 /journal.pone.0066650.t002

p a rt o f the plots u ndisturbed. T h e cores w ere h a n d le d like the

cores used for evaluating oxygen a n d carb o n exchange at the

sedim ent-w ater interface for the ex p erim ent 1. H ow ever, before

incu b atin g for w et respiration a n d determ in in g release o f T C 0 2

in the w ater colum n, the labelled cores w ere in cu b a ted for dry

fluxes d u rin g 6 h. A t the b eginning a n d a t the e n d o f the

incubation, air sam ples w ere collected using syringes a n d p u m p ed

into tubes co n tain in g soda lim e to trap C 0 2 a n d m easure the

C 0 2 derived from Ulva decom position. A L IC O R au to m a te d

C 0 2 analyzer was used to quantify C 0 2 release every hour.

Sedim ent-w ater exchange ra te a n d m acro fau n a d a ta w ere

gen erated as for ex p erim ent 1 (see “ A nalytical m easures” section).

Follow ing flux incubations for b o th experim ents, the cores w ere

sieved at 0.5 nin i to collect the m acrofauna. N o lugw orm was

included in the cores, m ea n in g th a t any observed p a tte rn

rep resen ted the result o f sedim ent a n d m acro fau n a alteration

due to Arenicola, b u t not the direct activity o f the lugw orm du rin g

incubation.

W ater T C 0 2 (wet fluxes), gaseous C 0 2 (dry flux), bulk sedim ent

a n d m acro fau n a collected in the labelled plots w ere analyzed for

carb o n isotope com position (8 C). T h e gaseous C 0 2 (dry flux)

c ap tu red using soda lim e was analyzed after acidification. T h e 13C

isotope signature for T C 0 2 dry a n d w et fluxes was analyzed using

a G C colum n coupled to a F in n in g an delta S m ass spectrom eter

IR M S . T h e carb o n isotopic com position for sedim ent, residual

detritus a n d anim als was d e term in ed using a Fisons elem ental

analyzer coupled to a F inningan delta S mass spectrom eter. 13C to

*~C ratio was referred to V ie n n a PD B a n d expressed in units o f %o.

R eproducibility o f the m easurem ents is b e tte r th a n 0.2%o [45].

T h e excess o f the heavy isotope o f carb o n (above background) was

expressed as total uptake (I) in m illigram s o f 13C. I was calculated

as the p ro d u c t o f excess 13C (E) a n d carb o n or biom ass (C):

I =E XC

A nalytical M e a s u r e s

In the laboratory, m acro fau n a w ere identified to the species

level, co u n te d a n d d ried a t 60"C for 48 h to o b tain dry w eight

biom ass to be used for stable isotope analyses relative to the

experim ent 2. T h e d etrital Ulva rem ain in g in the sam ples was also

collected, d ried a n d w eighed. C hlorophyll a was ex tracted in

darkness for 24 h a t 0 -4 "C using a 90% acetone solution. T h e

sedim ent was h om ogenized a n d sub-sam ples o f ab o u t 1 g dry

w eight w ere taken. Pigm ents w ere m easured spectrophotom etrically before a n d after 0.1 N HC1 acidification. Pre-com busted

(450"C for 3 h) sedim ent was used as a blank. M easurem ents for

bulk sedim ent O C w ere m ad e using a P erkin-E lm er C H N elem ent

analyzer o n freeze-dried m aterial, after c arb o n a te rem oval w ith

HC1.

Flux rates o f T C 0 2 a n d 0 2 b etw een the sedim ent a n d the

overlying w ater w ere estim ated as difference b etw een the initial

a n d the final T C 0 2 or 0 2 concentrations d u rin g d a rk incubation,

assum ing constant solute exchange w ith tim e. T h e oxygen

dissolved into the w ater sam ples was analyzed using the sta n d ard

m eth o d o f W inkler titration, while w ater T C 0 2 a n d po rew ater

D IC w ere d e term in ed by the flow in jection/diffusion cell

technique, w hich is based o n the diffusion o f C 0 2 th ro u g h a

hydrophobic m em b ran e into a flow o f deionized w ater, thus

gen eratin g a grad ien t o f conductivity p ro p o rtio n al to the

co n cen tratio n o f C 0 2.

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

E = F control

F¡¡„„pie

w here F indicates the fraction o f isotope a d d ed a n d it is calculated

as:

F = R /R +

1

w here R can be calculated from the m easured S 13C using R

referen ce o f 0.0112372:

4 f

\R sam ple / ^referen ce

I

X

10'

Statistical A n aly ses

F o r ex p erim ent 1, d a ta w ere analyzed w ith tw o-w ay orthogonal

m ixed m odel o f analysis o f variance (AN OVA ), w ith exclusion (2

levels: p ro c ed u ra l control A + a n d exclusion o f .4. marina, A —) a n d

d etrital e n rich m en t (3 o r 2 levels: 0, 200 a n d 600) as fixed a n d

ra n d o m factors, respectively. D etrital e n rich m en t was considered a

ra n d o m factor because the a m o u n t o f detritus to a d d was chosen

w ithin a range o f values to sim ulate conditions o f low a n d high

5

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects o f Ecosystem Engineer Loss

Table 3. T w o-w ay analyses o f variance for chlorophyll a, m a c r o fa u n a a b u n d a n c e a n d n u m b e r (N) of species.

C hlo ro phyll a

A bundance

N o f species

df

MS

F

MS

F

MS

F

Exclusion = E

1

72.23

1.27

0.48

0.69

0.03

0.00

Detrital enrichm ent = D

2

53.74

4.02

0.29

0.56

30.00

7.11

ExD

2

56.80

4.25

2.34

4.81

17.73

4.21

Residual

24

13.37

0.49

4.22

Significant values (P<0.05) are in bold. Data w ere sqrt-transformed for macrofauna abundance.

doi:10.1371 /journal.pone.0066650.t003

e nrichm ent, b u t no specific hypothesis con cern ed the chosen

am ounts. A significant interaction b etw een exclusion a n d detrital

e n rich m en t was expected if the exclusion o f A. marina ch an g ed the

response to d etrital enrichm ent. T hese analyses w ere done for the

total a b u n d an c e o f m acro fau n a individuals, n u m b e r o f m acrofau­

n a species, chlorophyll a, sedim ent O C , p o re w ate r D IC , w ater 0 2

a n d T C 0 2 exchange rate. C-cochran test was used to test for

residual v ariance hom ogeneity before ru n n in g the analyses. W h en

this test was significant (iP<0.05), d a ta w ere transform ed. Pooling

was done w h en P > 0.25. A posteriori m ultiple com parison S N K test

was ru n w h en interaction term was significant.

T h e variables collected for evaluating the recycling o f detrital

13C (experim ent 2) w ere analyzed w ith re p ea te d m easure

A N O V A , w ith tim e (6 , 8, 15 a n d 17 sam pling days from the

e n d o f detrital addition) as the re p ea te d m easure ra n d o m factor

a n d A. marina exclusion as fixed factor. Plots (2 levels) was nested in

exclusion. T h e interaction o f tim e w ith the exclusion trea tm e n t

was m easured over the interaction tim e x p lo t. W h en significant

interaction was found, the m ain effect exclusion was not

interp reted . A ssum ption ab o u t the correlation a m o n g the different

observations o f the re p ea te d m easure factor (time) was tested w ith

M au ch ley ’s sphericity test.

D ecom position rate o f m acroalgal detritus was estim ated by

fitting the first-order m odel:

Results

A fter the exclusion o f A. marina, no burrow s w ere visible in the

excluded plots (Fig. 2) a n d the n u m b e r o f burrow s in the

p ro c ed u ra l control (treatm ent A+) was com p arab le to th a t o f

na tu ra l sedim ent (m e a n ± S E , n = 5:8.7 2 ± 1.77 a n d 1 0 .3 3 ± 1 .1 7

burrow s m 3 for the n a tu ra l a n d the p ro c ed u ra l control,

respectively). O verall, th ere w ere no differences in m acro fau n a

species com position betw een the n a tu ra l sedim ent a n d the

p ro c ed u ra l control plots. M a c ro fa u n a a b u n d an c e (m ean ± SE,

n = 5) was 2 9 4 ± 4 2 a n d 2 2 0 ± 5 3 individual m 3, w hereas the

n u m b e r o f species was 1 0 ± 0 .2 a n d 1 0 ± 0 .5 for A + a n d n a tu ra l

sedim ent, respectively. T h erefo re, A + could be used as a control

for the effect o f lugw orm exclusion a n d d etrital m acroalgae.

O verall, in the n a tu ra l sedim ents a n d in the A + plots the

gastropod Hydrobia ulvae was num erically d o m inant, representing

90% o f m acro fau n a ab u n d an c e. T h e rem ain in g 10% was m ad e up

by oligochaetes (3%), deposit feeder polychaetes (3%) such as

spionids, nereids, capitellids a n d cirratulids a n d bivalves (3%),

m ainly Macoma balthica a n d Cerastoderma edule.

C a r b o n Availability a n d B e n th ic R e sp iratio n

A t the tim e o f sam pling, sedim ent organic carb o n (OC) did not

vary follow ing detrital enrichm ent, the exclusion o f A. marina or

their interactions (T able 1, Fig. 3a; A N O V A , T > 0 .05). M acroalgal

debris was still presen t in the sedim ent w here d etrital m acroalgae

w ere ad d ed a t the highest e n rich m en t level (treatm ent 600). T h e

biom ass o f this m acroalgal debris was sm aller in the lugw orm excluded sedim ent th a n in p ro c ed u ra l controls (m e a n ± SE:

lugw orm exclusion, trea tm e n t A —: 2 .3 ± 1 .4 gD W m 3; A+:

1 2 .0 ± 6 .6 gD W m - 3 ; A N O V A : F lt „ = 6.19, P = 0.038).

T h e re was a significant effect o f the in teractio n betw een

lugw orm exclusion a n d detrital e n rich m en t on p o re w ate r D IC to

the d e p th o f 1-2 cm (T able 1; Fig. 3b). In the n o n -en rich ed

sedim ent, p o re w ate r D IC c o n ce n tra tio n was h igher in the

lugw orm exclusion th a n in the control plots (SN K test at

P = 0.05: n o n -en rich ed plots, trea tm e n t 0: A —> A + ). M oreover,

in the lugw orm -exclusion plots, p o rew ater D IC was low er in the

en rich ed th a n in the n o n -en rich ed plots (SN K test at i 5= 0 .0 5 :

Arenicola exclusion, A —: 0 > 6 0 0 ). V alues in detrital-enriched,

lugw orm -excluded sedim ent w ere sim ilar to those m easu red for

the A+ trea tm e n t (Fig. 3b). A sim ilar p a tte rn was observed for

superficial (0-1 cm) a n d d eep er sedim ent (2-6 cm in Fig. 3b), b u t

no significant changes w ere m easured.

B oth A. marina exclusion a n d d etrital e n rich m en t o r their

interaction did n o t significantly change sedim ent-w ater exchanges

o f T C 0 2 a n d 0 2 n o r the RQ^ respiration coefficient ( T C 0 2: 0 2

ratio) (T able 2; Fig. 4).

B, = B0ek'

W h ere Bt is the g o f d etrital biom ass a t tim e t (days), B0 is the initial

biom ass, a t tim e 0 , a t the m o m e n t o f the second d etrital addition

a n d k is the specific decom position constant. T h e two detrital

additions w ere done at a distance o f one week, w hich m ay greatly

affect the estim ates o f B0. W e therefore considered the estim ates o f

residual Ulva as the sum o f two decom position curves, w ith the

sam e constant k b u t different decom posing time:

B t = B (0_ 1)ekl't+1) + B (0)ekt

T h e curves o f 13C b enthic inco rp o ratio n (including loss due to

respiration) w ere fitted to the logistic curve:

It= Y /(\+ q e -" )

q = ( Y - I 0) / I 0

W h ere Y is the 13C loss from m acroalgal decom position a n d r is

the capacity o f b e n thos to inco rp o rate C.

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

6

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects of Ecosystem Engineer Loss

(a)

60

□ 0

400

■ 200

■ 600

30 0

^

200

100

50

bù

40

I

£

30

-0.06

-0.08

-

H? 20

S

a

10

16

18

A significant interactio n betw een A. marina exclusion a n d detrital

en rich m en t was also found for m ac ro fau n a a b u n d an c e a n d

n u m b er o f species (T able 3). A b u n d an ce was low ered by the

highest level o f detrital en rich m en t in the plots w here A. marina was

present (Fig. 6a; S N K test: A+: 0 = 20 0 > 6 0 0 ). O verall, b o th the

d o m in a n t gastropod Hydrobia ulvae a n d all o th er rem aining

m ac ro fau n a decreased in a b u n d an ce, especially nereids, spionids

a n d bivalves (AN OVA : F 2, 94 = 4.26, P — 0.026 for H. ulvae, Fig. 6b;

F 2, 24 = 4.65, P — 0.019 for rem aining taxa, d a ta w ere square-root

transform ed; S N K tests for both: A+: 0 = 20 0 > 6 0 0 ). N u m b e r o f

species show ed a sim ilar p a tte rn , decreasing in response to the

highest level o f en rich m en t in the A + plots (Fi. 6G; S N K test: A+:

0 = 20 0 > 6 0 0 ). D etrital en rich m en t seem ed to not affect the

a b u n d an c e o f the lugw orm s as the n u m b er o f Arenicola burrow s

rem a in e d relatively stable at different levels o f detrital en rich m en t

(2 w ay A N O V A : F2t 12 = 0.88, P = 0.34, Fig. 6d).

20

£

0

b

15

2

10

tw

5

0

14

a n d a re re la tiv e to e x p e r im e n ts 2.

d o i:1 0 .1 3 7 1 /jo u rn a l.p o n e .0 0 6 6 6 5 0 .g 0 0 7

12

<N

12

Figure 7. Decom posing curves fo r Ulva detritus in lugw orm

excluded (tre atm en t A - ; square symbols in th e graphs) or

procedural control sedim ents (treatm en t A+; tria n g le symbols

in th e graph). S y m b o ls In d ic a te m e a n ( ± SE) for m a c ro a lg a l b io m a s s

o

C/3

•2h

"o

(U

Qh

GO

(d)

0.2

Tim e (days)

Hi

100

o

-

10

200

(c)

io

0.1

Ul

0

A-

T h e F a te o f D etrital C a r b o n

A+

T h e re w ere differences in the rate o f Ulva decom position

following A. marina exclusion. T h e decom position constant k was

—0.2 for the detritus ad d ed to the A. marina excluded sedim ent

(A— plots in Fig. 7). Interestingly, the A + plots did not fit well the

exponential curve using the sam e constant k th ro u g h the

decom position. R a th e r, at the beginning o f decom position, they

fitted k values betw een —0.06 a n d —0.08, w hereas at the en d they

fitted a K constant o f —0.1 (Fig. 7). T h e re w as a significant

interactio n betw een exclusion trea tm e n t a n d tim e after detrital

en rich m en t for the flux rate o f T C 0 2 from the sedim ent to the

w ater colum n (Table 4). M o re T 13C 0 2 was released by the

sedim ent in the exclusion trea tm e n t w ithin 6 days from burial

(Fig. 8a). R espiration rates w ere (m ean ± SE) 0 .8 4 ± 0 .2 5 a n d

0 .1 2 ± 0 .0 3 m g 13C m 2 day 1 for dry a n d w et fluxes, respectively.

P a rt o f the 13C rem a in e d in the b e nthos a n d it was in co rp o ra te d

in the bulk sedim ent a n d in the m acrofauna. T h e a m o u n t

in co rp o ra te d was variable am o n g plots, b u t it did not significantly

vary betw een exclusion treatm en ts or tim e (Table 4; Fig. 8 b —c). H.

ulvae in co rp o ra te d the largest a m o u n t o f G am o n g all m ac ro ­

fauna tax a (m ean ± SE: 3 .2 ± 0 .8 a n d 1 .2 ± 0 .4 m g 13C m 2, for

H . ulvae a n d rem ain in g fauna, respectively).

Figure 6. M ean (+1SE) for (a) to tal n um ber o f m acrofauna

individuals, (b) abundance o f Hydrobia ulvae, (c) n um ber of

m acrofauna species and (d) num bers o f Arenicola marina

burrows in th e plots w here th e m osquito net was buried

(A —) and in th e procedural control plots (A+) at th e end o f the

experim ent, e.g; 1 m onth from the second add itio n o f detrital

Ulva (0: no add itio n; 200:2 0 0 g W W w ere added tw ice at a 1

w e e k interval; 600 :6 0 0 g W W w ere added tw ice w ith a 1 w eek

interval). D ata w e re s a m p le d o n e m o n th a fte r d e trita l a d d itio n .

A sterisk in d ic a te s s ig n ific a n t d ifferen c e s.

d o i:1 0 .1 3 7 1 /jo u r n a l.p o n e .0 0 6 6 6 5 0 .g 0 0 6

Microalgal B iom ass a n d M a c r o f a u n a

T h e re w as a significant interactio n betw een A. marina exclusion

a n d detrital e n rich m en t for m icroalgal biom ass (T able 3; Fig. 5).

L ugw orm exclusion h a d a negative effect on m icroalgal biom ass in

the non -en rich ed plots (SN K test: 0: A + > A —). In the lugw orm excluded sedim ent, detrital en rich m en t en h an c ed m icroalgal

biom ass (SN K test: A —: 0 < 2 0 0 = 600). V alues w ere sim ilar to

those m easu red for the A + control plots (treatm ents 200 a n d 600

in Fig. 5).

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

7

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects o f Ecosystem Engineer Loss

Table 4. R e p e a te d m e a s u r e analyses of v ariance a n d sphericity t e s ts for t h e 13C in co rp o ra tio n in m a c r o f a u n a a n d bulk s e d im e n t,

a n d for t h e 1SC 0 2 released from t h e b e n t h o s ( b e n th ic respiration) d u rin g detrital d e c o m p o s i t io n a t a n in te r m e d i a t e level o f detrital

e n r i c h m e n t (200 gW W p l o t _1a d d e d twice).

M acrofaun a

df

MS

B ulk sed im e n t

F

MS

B enthic respiration

F

MS

F

Exclusion = E

1

5.97 1CT7

0.12

4.27

1CT4

0.22

1.52

1CT5

9.73

Time = T

3

3.13 10 -7

0.60

8.78

1CT4

1.02

1.84

1CT5

14.45

Residual (Plots)

2

4.96 1CT6

TxE

3

6.21

Residual (TxPlots)

6

5.21 10 -6

Sphericity test (y2) n = 6

7.80

IO-7

1.96 10 -3

0.12

8.79

1CT4

8.59 1CT4

4.83

1.56 1CT6

1.02

8.98

1CT6

7.07

1.27 1CT6

8.06

Significant values (P<0.05) are in bold. Sphericity te st was not significant.

doi:10.1371 /journal.pone.0066650.t004

Discussion

B ioturbation c an en h an ce solute p e n etratio n in d eeper

sedim ents, th eir exchange betw een the sedim ent a n d the overlying

w ater a n d re-distribute organic m aterial along the vertical profile

[36,37,41], As such, the loss o f species th a t are im p o rta n t

contributors to b io tu rb a tio n m ay greatly change the response to

d etrital decom position o f sedim ent biogeochem istry. In lab o rato ry

experim ents, for instance, A. marina a n d the polychaete Nereis

diversicolor w ere found to increase tu rn o v er o f carb o n a n d n utrients

d u rin g d etrital m acroalgal decom position [19,36], T h e exclusion

o f A. marina from intertidal sedim ents was thus expected to m odify

the biogeochem ical response to m acroalgal d etrital enrichm ent.

C onversely, a t the e n d o f decom position (1 m o n th after the second

enrichm ent) b enthic respiration ( 0 2 a n d T C 0 2 sedim ent-w ater

exchanges) a n d sedim ent organic c arb o n content did n o t change

as a n effect o f lugw orm exclusion.

Ulva a m o u n t a n d tim e o f sam pling (one m o n th after enrichm ent)

allow ed decom position a n d release o f a large q u a n tity o f organic

m atter, w hich could b e m ineralized o r accu m u lated in the

sedim ent, thereby m odifying sedim ent organic c arbon, inorganic

c arb o n dissolved in the interstitial w ater a n d fluxes a t the

sedim ent-w ater interface. Ulva halftim e decom position rate is

w ithin 15 days [30], By considering the range o f k constant

calculated for this study (betw een —0.06 a n d —0.2), a t least 85%

Ulva w ould b e decom posed at the tim e o f sam pling for b o th

e n rich m en t levels. If one considers th a t d ried sedim ent weighs

ab o u t 1600 g I- a n d Ulva organic c arb o n c o n te n t is a ro u n d 40%

o f d ried tissues [34], this decom posed detritus corresponds to

organic carb o n concentrations ra nging betw een 0.15 a n d 1.2%

sedim ent dry w eight for the top first cm , roughly 2 -1 0 tim es the

co n cen tratio n o f organic carb o n found in n a tu ra l sedim ents for

low a n d high enrichm ent, respectively (see the n o n -en rich ed

sedim ent in Fig. 2a). T h e lack o f sedim ent carb o n accum ulation

a n d changes in T C 0 2 fluxes a t the sedim ent-w ater interface

indicated th a t the b enthic system was able to rem ove the carb o n

derived from in situ decom position a n d th a t b io tu rb a tio n did not

play a cen tral role in d etrital carb o n recycling.

It is im p o rta n t to re-iterate th a t fluxes w ere m easured du rin g

12 h d ark incubation o f sedim ent cores w ithout lugw orm s, w hich

indicated the overall indirect effect o f lugw orm s on d etrital benthic

m ineralization, b u t did not include any direct effects o f lugw orm s

due to b u rro w ventilation d u rin g the p e rio d o f incubation. T h e

im p o rtan ce o f ventilation was instead assessed in the field by

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

m easuring p o re w ate r D IC , w hich increased after lugw orm

rem oval, in dicating a decreased solute exchange due to A. marina

loss. Interestingly, these changes w ere variable along the vertical

sedim ent profile a n d w ere offset b y the add itio n o f detrital

m acroalgae, w hich supported the idea th a t fast m ineralization o f

d etrital c arb o n in these sedim ents is only in p a rt due to

b io tu rb atio n . T h e com plexity o f the relationships betw een species,

functions a n d response to d isturbance c an increase w ith increasing

ecological realism [15,46], O u r experim ents w ere done in situ a n d

they w ere designed to test effects o f A. marina u n d e r n a tu ra l

e nvironm ental conditions. D etrital m acroalgae w ere deliberately

a d d ed to the sedim ent, w ithout using artificial nets th a t could lim it

d etrital loss. T his m eth o d exposed decom posing detritus to tides

a n d waves, especially w h en detritus re m a in e d at the sedim ent

surface. T h e role o f b io tu rb a tio n on sedim ent biogeochem istry has

b e en m ainly assessed th ro u g h lab o ra to ry studies. T h e few field

studies o n the role o f Arenicola on porew ater, fluxes a n d organic

m atter decom position have revealed th a t its role m ay vary a n d

decrease considerably in n a tu re [19,37,47]. By co m p arin g field to

lab o ra to ry experim ents, it was found, for instance, th a t solute

exchange was m o re variable in the field because it was n o t only

ruled by b io tu rb a tio n b u t also by advection related to waves a n d

tides a n d b y differences in the reactivity o f sedim ent organic

m atter related to the com plexity o f biological com m unities o f

p rim a ry p roducers a n d consum ers [47]. T h is is p articularly true

w hen experim ents are done in p erm eab le sedim ent, w here A.

marina is often a d o m in a n t species [48], In these sedim ents,

hydrodynam ics can e n h an c e advective flow from the p o rew ater to

the overlying w ater colum n, rule the exchange o f solutes a n d

organic m a tte r a t the sedim ent-w ater interface a n d overw helm the

biological effect o f b io tu rb a tio n [49]. A lthough o u r experim ents

w ere done in a relatively sheltered sand flat, as indicated b y the

dom inance o f fine-grained sand, num erous ripple m arks w ere

visible at low tide (Fig. 2) a n d they p ro bably indicated strong

hydrodynam ics gen erated b y w aves a n d tides. In these sedim ents,

hydrodynam ics could accelerate the exchange o f solutes p ro d u c ed

d u rin g d ecom position, the rem oval o f m acroalgal detritus from the

sedim ent a n d override the effect o f b io tu rb a tio n o n the response o f

sedim ent biogeochem istry to d etrital m acroalgae.

T h e decom position ra te o f Ulva in these sedim ents was fast, as

indicated b y the estim ated k constants (k = —0.2 a n d —0.1 for A —

a n d A+, respectively; Fig. 7). T hese values w ere at the lim it o r even

exceeded the range o f values typical o f Ulva detritus, w hich varies

betw een —0.04 a n d —0.1 [34], M o re im portantly, the estim ated k

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects o f Ecosystem Engineer Loss

b enthic response to detrital m acroalgae, A. marina could represent

an im p o rta n t sink for detritus a n d it could m odify in situ

decom position rate, as found for o th er burro w in g b ioturbators

[39,50]. T hese species can m echanically b u ry m acroalgae in their

funnels, th ereb y decreasing detritus availability to surface sedim ent

a n d slowing dow n decom position rate, while m ain tain in g a pool o f

organic m atter in the sedim ent. B uried detritus a n d slowed

decom position rate could, in tu rn , m odify m ineralization process­

es. In this study, a peak in T ’CCE release to the w ater colum n

was identified at an early stage o f decom position in A. marinaexcluded sedim ent plots, suggesting th a t the loss o f A. marina

accelerated the m ineralization o f d etrital Ulva at an early stage o f

decom position. T his explanation o f increased m ineralization

following A. marina loss was su pported by the finding th a t

p o re w ate r D IC decreased in response to detrital addition in A.

marina excluded sedim ents. In addition, sim ultaneously to this

decrease, m acroalgal biom ass increased. Probably, w ithout the

m echanical action o f burying m acroalgal fragm ents by Arenicola,

detrital m acroalgae rem ain in g on sedim ent surface a n d deco m ­

posing faster released nutrients th a t en h an c ed bacterial m eta b o ­

lism a n d th eir c arbon consum ption. E vidence for increased c arbon

consum ption d uring biom ass decom position has b een fo und for

p la n t litter in freshw ater ecosystem s [51,52]. In addition, benthic

m icroalgae are often regulated by botto m -u p processes [53] an d

they could greatly benefit from n u trie n t release, thereb y co n trib ­

u ting to recycling the m ineralized detrital carbon. Interestingly,

detrital en rich m en t a n d lugw orm s h a d sim ilar effects on m icro ­

algal biom ass. P robably, b o th lugw orm bioirrigation a n d detrital

decom position can provide nutrients necessary to regulate

m icroalgal grow th [19,28,37,47].

A. marina is believed to influence the assem bly rules a n d the

distribution o f m acro fau n a and, as such, th eir pa tte rn s o f response

to disturbances by altering the sedim entary h a b ita t (e. g. [37,41]).

O u r results show ed a negative effect o f A. marina on m acro fau n a

response to detrital addition since bo th m acro fau n a abu n d an ce

a n d diversity decreased following the highest level o f en rich m en t

in presence o f lugw orm s. T h e increased detrital burial b y T . marina

could play a central role in d eterm ining this response. Patches o f

detrital m acroalgae in sedim ents can govern the spatial an d

tem p o ral variability o f m acro fau n a pa tte rn s o f distribution. T h e

presence o f detritus m ay decrease nu m b ers o f individuals an d

diversity because o f hypoxia d u rin g decom position. O n c e detritus

has decom posed, fast recolonizing taxa can p rom ptly occupy the

previously d isturbed patches a n d benefit from increased food

supply [29]. D etrital burial due to lugw orm activity pro b ab ly

prolo n g ed hypoxic conditions a n d slowed dow n m acro fau n a

recovery. T h e decrease in a b u n d an c e com m on to all taxa an d

the loss o f diversity could co rro b o rate this explanation as anoxic

conditions related to detrital decom position deplete m ost taxa

a b u n d an c e a n d diversity [29]. M oreover, burial could decrease

detrital availability to surface consum ers a n d therefore prev en t

th eir colonization, once hypoxia ceases. M acroalgal supply to

sedim ent surface can rep resen t an im p o rta n t source o f food for

surface grazers a n d detritivores, such as the g a stropod Hydrobia

ulvae [34,54], P a rt o f detrital c arbon was tran sferred to m ac ro fau ­

na, especially to H. ulvae (experim ent 2, Fig. 7c), w hich was the

num erically d o m in a n t species in these area. Its im p o rta n t role for

detrital c arb o n tran sp o rt to the food w eb was found previously in

the surro u n d in g area [34], T his species is highly m obile a n d it

crawls on sedim ent surface for feeding. Its local a b u n d an c e m ight

thus vary rapidly following food availability on surface sedim ent.

In sum m ary, ou r field ex p erim ent show ed th a t A. marina can be

an im p o rta n t sink for detrital Ulva. H ow ever, conversely to w h at it

should be expected based on cu rre n t research know ledge, this

(a)

5.0

"b

(N

4.0

a

ÖD

(N

O

3.0

2.0

O

1.0

H

0.01

m

0

2

4

LO 12

14

16

18

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

(c)

10

O

co

bû

8

6

4

Ö

¡3

f o3

2

ou

0

H—I

o

03

0

2

4

Time (days)

Figure 8. M ean ± SE fo r (a) T 13C 0 2 released from th e sedim ent

to th e w a te r colum n (sum o f d ry and w e t fluxes); (b) am o u n t of

13C organic carbon in th e b u lk sedim ent (averaged o ver d ep th

p ro file ) and (c) a m o u n t o f 13C carbon in c o rp o ra te d by

m acrofauna. D ata a re fitte d to th e LOESS s m o o th in g w ith a n interv al

o f 4 a n d 1 p o ly n o m ia l d e g re e . V alu es a re a v e r a g e d o v e r th e tw o p lo ts

w h e re A. m arina w a s e x c lu d e d (tr e a tm e n t A —; s q u a r e sy m b o ls in th e

g ra p h s ) a n d th e tw o p ro c e d u ra l c o n tro l p lo ts (tr e a tm e n t A+; tria n g le

sy m b o ls in th e g ra p h ). D ata refers to th e e x p e r im e n t 2. A sterisk

in d ic a te s s ig n ific a n t d ifferen c e s.

d o i:1 0 .1 3 7 1 /jo u rn a l.p o n e .0 0 6 6 6 5 0 .g 0 0 8

constant for the lugw orm -exclusion sedim ent was twice th a t o f the

control plots. In addition, the biom ass o f m acroalgal debris was, on

average, 6 tim es larger in controls th a n in lugw orm -excluded

sedim ents (2 a n d 12 g D W p e r p lot 1 for A + a n d A —,

respectively). T his m ay brin g to the conclusion th a t despite

hydrodynam ics could play an im p o rta n t role in d eterm ining

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

9

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects o f Ecosystem Engineer Loss

species has m o d erate, som etim es negative effects on the response

to d etrital en ric h m e n t o f sedim ent biogeochem istry a n d m acro ­

fauna. A. marina loss causes the sedim entary ecosystem to becom e a

faster recycler o f detrital m acroalgae, en h an c in g d etrital loss,

c arb o n consum ption a n d m ineralization. T his m ay b rin g to the

conclusion th a t the loss o f this species m ig h t be u n im p o rta n t or

som ew hat beneficial for certain intertidal ecosystem s. H ow ever,

fast recycling a n d d etrital dispersal could u n d e rm in e carb o n

storage capacity o f benthos an d , in tu rn , the stability o f w hole

estuarine ecosystem facing organic en ric h m e n t a n d eu tro p h ica ­

tion.

T hese findings clearly dem onstrate th a t u n d e r n a tu ra l c ondi­

tions, the local extinction o f a n ecosystem engineer m ay have

com plex effects on the ecological stability o f m arin e sedim ent

biogeochem istry a n d b en th ic com m unities o f consum ers. T h ey

also highlight the im p o rtan ce o f p erform ing experim ents u n d e r

na tu ra l conditions if w e are to u n d e rstan d a n d p re d ic t the response

o f ecosystem s to p e rtu rb a tio n a n d species loss.

Acknowledgments

T he authors wish to thank the technicians for their invaluable help in the

chem ical analyses and E. W eerm an, JJ Jan sen and F M ontserrat and

num erous other students for their help in the field. S. T hrush is kindly

thanked for his critical revision o f an early version of this MS. This study is

p a rt of the B IO FU SE project, w ithin the M A RBEF network of excellence.

Author Contributions

Conceived an d designed the experim ents: F R BG. Perform ed the

experiments: F R BG FG VDS. Analyzed the data: F R BG FG VDS.

C ontributed reagents/m aterials/analysis tools: TTM. W rote the paper: FR

BG FG V D S JJM .

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

G rim e J P (1997) E c o lo g y - B io d iv ersity a n d e c o sy ste m fu n c tio n : T h e d e b a te

d e e p e n s. S c ien c e 277: 1 2 6 0 -1 2 6 1 .

M c C a n n K S (2000) T h e d iv ersity -sta b ility d e b a te . N a tu re 405: 2 2 8 -2 3 3 .

W o rm B, B a rb ie r E B , B e a u m o n t N , D u ffy J E , F o lk e C , e t al. (2006) Im p a c ts o f

b io d iv e rsity loss o n o c e a n e c o sy ste m services. S c ien c e 314: 78 7 —790.

T ilm a n D , D o w n in g AT. (1994) B io d iv ersity a n d sta b ility in g rasslan d s. N a tu re

367: 3 6 3 -3 6 5 .

Y a c h i S, L o re a u M (1999) B io d iv ersity a n d eco sy stem p ro d u c tiv ity in a flu c tatin g

e n v iro n m e n t: T h e in s u ra n c e h y p o th esis. P ro c e e d in g s o f th e N a tio n a l A c a d e m y

o f S cien ces o f th e U n ite d S ta te s o f A m e ric a 96: 1463—1468.

D o w n in g A , L e ib o ld M (2010) Sp ecies ric h n e ss fac ilitate s e co sy stem resilie n c e in

a q u a tic f o o d w ebs. F re sh w a te r B io lo g y 55: 2 1 2 3 —2137.

Ives A , C a r p e n te r S (2007) S ta b ility a n d d iv ersity o f eco sy stem s. Scien ce: 5 8 —62.

R a ffa e lli D G , R a v e n J A , P o o le L J {1998) E c o lo g ic a l im p a c t o f g re e n m a c ro a lg a l

b lo o m s. O c e a n o g r a p h y a n d M a rin e B iology, a n A n n u a l R e v ie w 36: 9 7 —125.

27.

F o r d R B , T h r u s h SF, P r o b e r t P K {1999) M a c r o b e n th ic c o lo n is a d o n o f

d istu rb a n c e s o n a n in te rtid a l san d flat: th e in flu e n ce o f se aso n a n d b u r ie d algae.

28.

29.

P fiste re r A , S c h m id B (2002) D iv e rs ity -d e p e n d e n t p r o d u c tio n c a n d e c re a se th e

sta b ility o f e c o sy ste m fu n c tio n in g . N a tu re 4 1 6 : 8 4 —86.

Allison G (2004) T h e in flu e n ce o f sp ecies d iv ersity a n d stress in te n sity o n

c o m m u n ity re sista n c e a n d resilien ce. E c o lo g ic a l M o n o g ra p h s 74: 117—134.

E m m e r s o n M C , S o la n M , E rn es C , P a te rs o n D M , R a ffa e lli D (2001) C o n s is te n t

R o ssi F {2006) S m all-scale b u r ia l o f m a c ro a lg a l d e tritu s in m a r in e se d im e n ts:

E ffects o f U lv a sp p . o n th e sp a tia l d istrib u tio n o f m a c r o fa u n a assem blages.

J o u r n a l o f E x p e rim e n ta l M a rin e B io lo g y a n d E c o lo g y 332: 8 4 —95.

31.

B o la m S G , F e r n a n d e z T F , R e a d P , R a ffa e lli D {2000) E ffects o f m a c ro a lg a l m ats

o n in te rtid a l san d flats: a n e x p e rim e n ta l stu d y . J o u r n a l o f E x p e rim e n ta l M a rin e

33.

resp o n se s o f a lg a e to d is tu rb a n c e in m o n o - a n d m u lti-sp e cie s assem b lag es.

O e c o lo g ia 157: 5 0 9 - 5 1 9 .

R o ssi F , V o s M , M id d e l b u r g J (2009) S p ecies id e n tity , d iv ersity a n d m ic ro b ia l

34.

35.

e ffe c t o f d e c o m p o s in g

a c c u m u la to in s

A b s tra c ts o f P a p e rs o f th e A m e ric a n C h e m ic a l S o ciety 221: U 5 3 8 —U 5 3 8 .

B ra e c k m a n U , P ro v o o s t P , M o e n s T , S o e ta e rt K , M id d e l b u r g J , e t al. (2011)

B iological vs. P h y sica l M ix in g E ffects o n B e n th ic F o o d W e b D y n a m ic s. Plos O n e

6: : - e l 8 0 7 8 . d o i:1 0 .1 3 7 1 /jo u rn a l.p o n e .0 0 1 8 0 7 8 .

21. L o h r e r A M , T h r u s h SF, G ib b s M M (2004) B io tu rb a to rs e n h a n c e eco sy stem

fu n c tio n th ro u g h c o m p le x b io g e o c h e m ic a l in te ra c tio n s . N a tu r e 4 3 1 : 1092—1095.

o f se a w e e d . J o u r n a l o f

E x p e r im e n ta l M a rin e B iology a n d E c o lo g y 96: 199—212.

R o ssi F {2007) R e c y c le o f b u r ie d m a c ro a lg a l d e tritu s in se d im e n ts: use o f d u a l­

lab e llin g e x p e rim e n ts in th e field. M a rin e B io lo g y 150: 1073—1081.

G o d b o ld J A , S o la n M , K illh a m K {2009) C o n s u m e r a n d re s o u rc e d iversity

effects o n m a r in e m a c ro a lg a l d e c o m p o s itio n . O ik o s 118: 77—86.

36.

H a n s e n K , K riste n s e n E {1998) T h e im p a c t o f th e p o ly c h a e te N e re is d iv ersic o lo r

a n d e n ric h m e n t w ith m a c ro a lg a l { C h a e to m o rp h a lin u m ) d e tritu s o n b e n th ic

m e ta b o lis m a n d n u trie n t d y n a m ic s in o rg a n ic -p o o r a n d o rg a n ic -ric h se d im e n t.

J o u r n a l o f E x p e rim e n ta l M a rin e B io lo g y a n d E c o lo g y 231: 2 0 1 —223.

37.

O ’B rie n A , V o lk e n b o rn N , v a n B eu se k o m J , M o rris L , K e o u g h M {2009)

I n te ra c tiv e effects o f p o r e w a te r n u trie n t e n ric h m e n t, b io tu r b a tio n a n d s e d im e n t

c h a ra c te r is tic s o n b e n th i c a s se m b la g e s in s a n d y

E x p e r im e n ta l M a rin e B iology a n d E cology: 5 1 —59.

s e d im e n ts . J o u r n a l

of

38.

D ’A n d r e a A , D e W itt T {2009) G e o c h e m ic a l eco sy stem e n g in e e rin g b y th e m u d

s h rim p U p o g e b ia p u g e tte n s is { C ru stacea: T h a la s s in id a e ) in Y a q u in a B ay,

O re g o n : D e n s ity -d e p e n d e n t effects o n o rg a n ic m a tte r re m in e ra liz a tio n a n d

n u trie n t cycling. L im n o lo g y a n d O c e a n o g r a p h y 54: 1911—1932.

39.

V o n k J , K n e e r D , S ta p e l J , A sm u s H {2008) S h rim p b u r ro w in tro p ic a l seagrass

m ea d o w s: A n i m p o r ta n t sin k fo r litte r. E s tu a rin e C o a s ta l a n d S h e lf S c ien c e 79:

40.

20.

41.

7 9 -8 5 .

M e y sm a n F JR , G a la k tio n o v E S , G rib s h o lt B, M id d e lb u r g J J {2006) B io irrig a tio n

in p e rm e a b le sed im en ts: A d v e c tiv e p o r e - w a te r t ra n s p o rt in d u c e d b y b u r ro w

v e n tila tio n . L im n o lo g y a n d O c e a n o g r a p h y 51: 142—156.

V o lk e n b o rn N , R e ise K {2006) L u g w o rm ex c lu sio n e x p e rim e n t: R e sp o n se s b y

d e p o s it f e e d in g w o rm s to b io g e n ic h a b it a t tra n s fo r m a tio n s . J o u r n a l O f

E x p e r im e n ta l M a rin e B iology A n d E c o lo g y 330: 169—179.

22.

E k l o f J , v a n d e r H e id e T , D o n a d i S, v a n d e r Z e e E , O ’H a r a R , e t al. (2011)

H a b i ta t- M e d ia te d F a c ilita tio n a n d C o u n te r a c tin g E c o s y s te m E n g in e e r in g

In te ra c tiv e ly In flu e n c e E c o sy ste m R e sp o n se s to D is tu rb a n c e . Plos O n e 6:

e 2 3 2 2 9 .-d o i: 1 0 .1 3 7 1 /jo u r n a l.p o n e .0 0 2 3 2 2 9 .

23. N o rk k o J , R e e d D C , T im m e r m a n n K , N o rk k o A , G u sta fsso n B G , e t al. {2012) A

w e lc o m e c a n o f w o rm s? H y p o x ia m itig a tio n b y a n in vasive species. G lo b a l

42.

43.

C h a n g e B iology 18: 4 2 2 - 4 3 4 . d o k lO .l 1 1 1 / j . 1 3 6 5 - 2 4 8 6 .2 0 1 1 .0 2 513.x.

E is e n h a u e r N , M ilc u A , S a b a is A , S c h e u S {2008) A n im a l E c o sy ste m E n g in e e rs

M o d u la te th e D iv e rsity -In v asib ility R e la tio n s h ip . Plos O n e 3.

C e b r ia n J {2004) R o le o f firs t-o rd e r c o n su m e rs in e co sy stem c a rb o n flow.

E c o lo g y L e tte rs 7: 2 3 2 -2 4 0 .

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

B io lo g y a n d E c o lo g y 249: 123—137.

H u ll S C {1987) M a c ro a lg a l m a ts a n d sp ecies a b u n d a n c e : a field e x p e rim e n t.

E s tu a rin e C o a s ta l a n d S h e lf S c ien c e 25: 5 1 9 - 5 3 2 .

T h r u s h S F {1986) T h e su b litto ra l m a c r o b e n th ic c o m m u n tiy s tru c tu re o f a n irish

s e a -lo u g h :

16. J o n e s C G , L a w to n J H , S h a c h a k M (1994) O rg a n is m s as e c o sy ste m e n g n e ers.

O ik o s 69: 3 7 3 -3 8 6 .

17. B erke S (2010) F u n c tio n a l G ro u p s o f E c o sy ste m E n g in e ers: A P ro p o s e d

C la ssific a tio n w ith C o m m e n ts o n C u r r e n t Issues. In te g ra tiv e a n d C o m p a ra tiv e

B iology 50: 1 4 7 -1 5 7 .

18. K ris te n s e n E , P e n h a -L o p e s G , D elefo sse M , V a ld e m a r s e n T , Q u i n ta n a C O , e t

al. (2012) W h a t is b io tu r b a tio n ? T h e n e e d fo r a p re c is e d e fin itio n fo r f a u n a in

a q u a tic sciences. M a rin e E c o lo g y P ro g re ss S eries 446: 28 5 —302.

19. K ris te n s e n E (2001) I m p a c t o f p o ly c h a e te s {Nereis a n d A re n ic o la ) o n s e d im e n t

b io g e o c h e m is try in c o a sta l a re a s: P a st, p re s e n t, a n d f u tu re d e v e lo p m e n ts.

25.

2 9 -3 9 .

K e la h e r B P , L e v in to n J S {2003) V a r ia tio n in d e trita l e n ric h m e n t c a u se s sp atio te m p o r a l v a ria tio n in so ft-se d im e n t a ssem b lag es. M a rin e E c o lo g y P ro g re ss S eries

261: 8 5 -9 7 .

30.

32.

c a rb o n flow in re a s s e m b lin g m a c r o b e n th ic c o m m u n itie s. O ikos: 5 0 3 —51 2 .

13. S o la n M , C a r d in a le BJ, D o w n in g A L , E n g e lh a r d t K A M , R u e s in k J L , e t al.

(2004) E x tin c tio n a n d e co sy stem fu n c tio n in th e m a r in e b e n th o s . S c ien c e 306:

1 1 7 7 -1 1 8 0 .

14. B o la m S G , F e rn a n d e s T F , H u x h a m M (2002) D iv e rsity , b io m a s s , a n d eco sy stem

pro ce sse s in th e m a r in e b e n th o s . E c o lo g ic a l M o n o g ra p h s 72: 5 9 9 —6 1 5 .

15. R o m a n u k T , V o g t R , K o la s a J (2009) E c o lo g ic a l re a lism a n d m e c h a n ism s b y

w h ic h div ersity b e g e ts stab ility . O ik o s 118: 8 1 9 - 8 2 8 .

24.

M a rin e E c o lo g y P ro g re ss S eries 191: 163—174.

R o ssi F , U n d e r w o o d A J {2002) S m a ll-sc a le d is tu rb a n c e a n d in c re a se d n u trie n ts

a s in flu e n ce s o n in te rtid a l m a c r o b e n th ic assem b lag es: e x p e rim e n ta l b u r ia l o f

w ra c k in d iffe re n t in te rtid a l e n v iro n m e n ts . M a rin e E c o lo g y P ro g re ss S eries 241:

p a tte rn s a n d th e id io sy n c ra tic effects o f b io d iv e rsity in m a r in e ecosystem s.

N a tu r e 411: 7 3 -7 7 .

11. G o o d se ll I J , U n d e r w o o d A J (2008) C o m p le x ity a n d id io sy n c ra sy in th e

12.

26.

44.

N o rk k o A , B o n s d o rff E {1996) P o p u la tio n resp o n se s o f c o a sta l z o o b e n th o s to

stress in d u c e d b y d riftin g a lg a l m ats. M a rin e E c o lo g y P ro g re ss S eries 140: 141—

151.

B u c h s b a u m R , V a lie la I, S w ain T , D z ie rz e sk i M , A lle n S {1991) A v a ila b le A n d

R e fra c to ry N itro g e n I n D e tritu s O f C o a s ta l V a s c u la r P la n ts A n d M a c ro a lg a e .

M a rin e E co lo g y -P ro g ress S eries 72: 131—143.

N e d e r g a a r d R I , R is g a a rd -P e te rs o n N , F in s te r K {2002) T h e im p o r ta n c e o f

s u lfate re d u c tio n a sso c ia te d w ith U lv a la c tu c a th alli d u r in g d e c o m p o s itio n : a

m eso c o sm e x p e rim e n t. J o u r n a l o f E x p e rim e n ta l M a rin e B io lo gy a n d E c o lo g y

275: 1 5 -2 9 .

10

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650

Complex Effects o f Ecosystem Engineer Loss

45.

H e r m a n P M J. M id d e lb u rg J J . W id d o w s J , L u c a s C H . H e ip C H R (2000) S ta b le

iso to p es as tro p h ic tra c e rs: c o m b in in g field s a m p lin g a n d m a n ip u la tiv e lab e llin g

o f f o o d reso u rc e s fo r m a c ro b e n th o s . M a rin e E c o lo g y P ro g re ss S eries 204: 79—92.

46. M c k ie B. S c h in d le r M . G e ssn e r M . M a lm q v is t B (2009) P la c in g b io d iv e rsity a n d

e c o sy ste m fu n c tio n in g in c o n te x t: e n v iro n m e n ta l p e rtu r b a tio n s a n d th e effects o f

species ric h n e ss in a s tre a m field e x p e rim e n t. O e c o lo g ia : 7 5 7 —770.

4 7 . P a p a s p y r o u S, K r is te n s e n E , C h r i s t e n s e n B (2 0 0 7 ) A r e n ic o la m a r i n a

(P o ly c h a e ta ) a n d o rg a n ic m a tte r m in e ra lisa tio n in s a n d y m a r in e se d im e n ts: I n

situ a n d m ic ro c o s m c o m p a ris o n . E s tu a rin e C o a s ta l a n d S h e lf S c ien c e 72: 2 13—

222.

4 8 . N e e d h a m H , P ild itc h C , L o h r e r A , T h r u s h S (2 011) C o n te x t-S p e c ific

B io tu rb a tio n M e d ia te s C h a n g e s to E c o sy ste m F u n c tio n in g . E co sy stem s 14:

1 0 9 6 -1 1 0 9 .

49. H u e tte l M , R o y H . P r e c h t E. E h re n h a u s s S (2003) H y d r o d y n a m ic a l im p a c t o n

b io g e o c h e m ic a l p ro ce sse s in a q u a tic se d im e n ts. H y d ro b io lo g ia 4 9 4 : 23 1 —236.

PLOS ONE I www.plosone.org

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

R e tr a u b u n A , D a w s o n M , E v a n s S (1996) T h e ro le o f th e b u r ro w f u n n e l in

fe e d in g p ro ce sse s in th e lu g w o rm A re n ic o la m a r in a (L). J o u r n a l o f E x p e rim e n ta l

M a rin e B io lo g y a n d E c o lo g y 202: 1 0 7 -1 1 8 .

F o n ta in e S, B a r d o u x G . A b b a d ie L. M a rio tti A (2004) C a r b o n in p u t to soil m a y

d e c re a s e soil c a rb o n c o n te n t. E c o lo g y L e tte rs 7: 314—320.

L e n n o n J T (2004) E x p e rim e n ta l e v id e n c e th a t te rre s tria l c a rb o n subsidies

in c re a se C 0 2 flu x fro m lak e eco sy stem s. O e c o lo g ia 138: 5 8 4 —591.

H ille b r a n d H . W o rm B. L o tz e H (2000) M a rin e m ic ro b e n th ic c o m m u n ity

s tru c tu re r e g u la te d b y n itro g e n lo a d in g a n d g ra z in g p re ssu re . M a rin e E c o lo g y

P ro g re ss S eries 204: 2 7 -3 8 .

R ie ra P (2010) T r o p h ic p lastic ity o f th e g a s tro p o d H y d r o b ia u lv ae w ith in a n

in te rtid a l b a y (R oscoff. F ra n ce ): A stab le iso to p e ev id e n c e . J o u r n a l o f Sea

R e s e a rc h 63: 78—83.

11

June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e66650