WARWICK ECONOMIC RESEARCH PAPERS 1943 to 1962

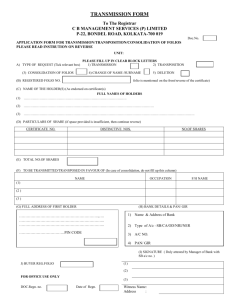

advertisement