Asking Questions Three laws:

advertisement

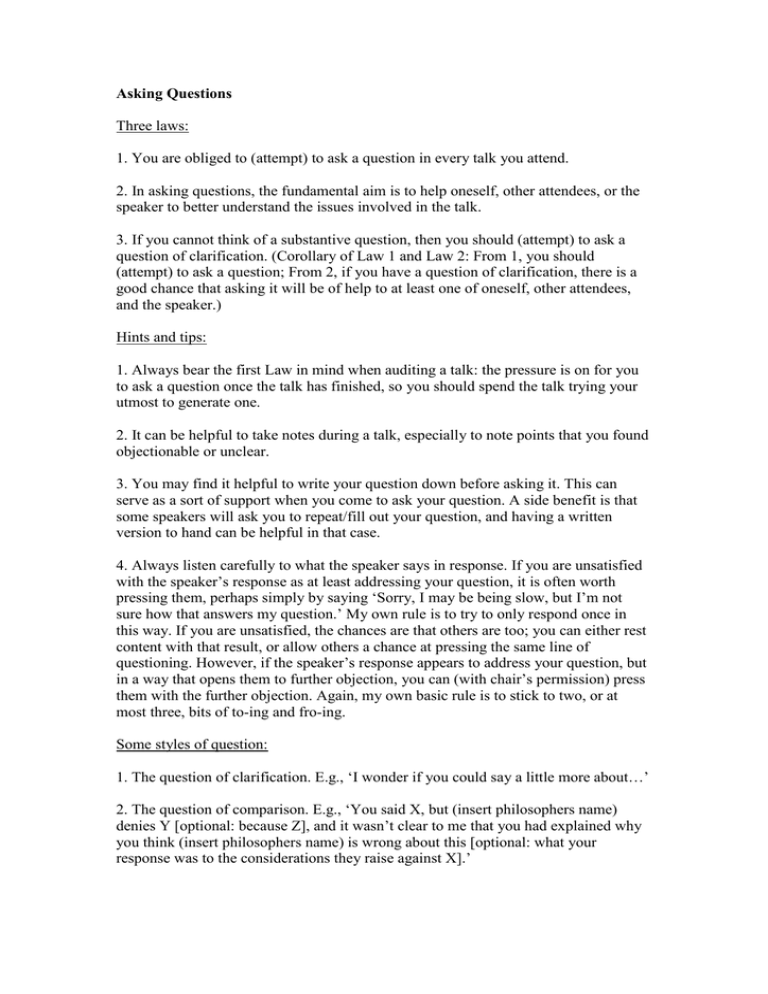

Asking Questions Three laws: 1. You are obliged to (attempt) to ask a question in every talk you attend. 2. In asking questions, the fundamental aim is to help oneself, other attendees, or the speaker to better understand the issues involved in the talk. 3. If you cannot think of a substantive question, then you should (attempt) to ask a question of clarification. (Corollary of Law 1 and Law 2: From 1, you should (attempt) to ask a question; From 2, if you have a question of clarification, there is a good chance that asking it will be of help to at least one of oneself, other attendees, and the speaker.) Hints and tips: 1. Always bear the first Law in mind when auditing a talk: the pressure is on for you to ask a question once the talk has finished, so you should spend the talk trying your utmost to generate one. 2. It can be helpful to take notes during a talk, especially to note points that you found objectionable or unclear. 3. You may find it helpful to write your question down before asking it. This can serve as a sort of support when you come to ask your question. A side benefit is that some speakers will ask you to repeat/fill out your question, and having a written version to hand can be helpful in that case. 4. Always listen carefully to what the speaker says in response. If you are unsatisfied with the speaker’s response as at least addressing your question, it is often worth pressing them, perhaps simply by saying ‘Sorry, I may be being slow, but I’m not sure how that answers my question.’ My own rule is to try to only respond once in this way. If you are unsatisfied, the chances are that others are too; you can either rest content with that result, or allow others a chance at pressing the same line of questioning. However, if the speaker’s response appears to address your question, but in a way that opens them to further objection, you can (with chair’s permission) press them with the further objection. Again, my own basic rule is to stick to two, or at most three, bits of to-ing and fro-ing. Some styles of question: 1. The question of clarification. E.g., ‘I wonder if you could say a little more about…’ 2. The question of comparison. E.g., ‘You said X, but (insert philosophers name) denies Y [optional: because Z], and it wasn’t clear to me that you had explained why you think (insert philosophers name) is wrong about this [optional: what your response was to the considerations they raise against X].’ 3. The counterexample. E.g., ‘If I understood you correctly, you said X. But suppose Y. Wouldn’t that be a counterexample to X?’ 4. The putative inconsistency. E.g., ‘You appeared to say X at the start of your talk, and then to say Y later in your talk. Isn’t there at least a tension between X and Y?’ 5. The additional case. E.g., ‘If your proposal is viable, one would expect it to cover Y. Do you think that’s right? And if you do, I wonder if you could say something about how your account does cover Y [optional: because there would appear to be the following difficulties].’ 6. The distinction. E.g., ‘You appeared to treat the following claims (/case/etc.) as on a par, but there appears to be a distinction between them [optional: because…] Guy Longworth g.longworth@mac.com