INFORMATION, COLLEGE DECISIONS AND FINANCIAL AID:

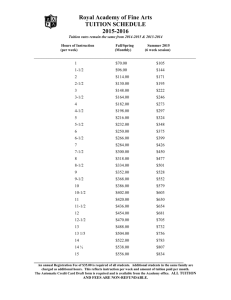

advertisement