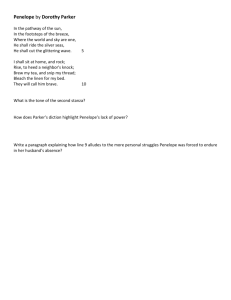

DESPERATELY SEEKING Ψ CHARLES TRAVIS Institute of Philosophy-University of Porto King’s College London

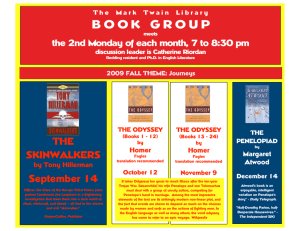

advertisement