HEALTH SAFETY, AND ENVIRONMENT

advertisement

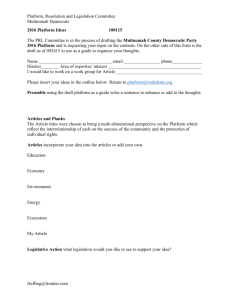

HEALTH a nd INFRASTRUCTURE, SAFETY, AND ENVIRONMENT CHILDREN AND FAMILIES EDUCATION AND THE ARTS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INFRASTRUCTURE AND TRANSPORTATION This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org ExploreRAND Health RAND Infrastructure, Safety, and Environment View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discussions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research professionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity. TECHNIC A L REP O RT National Evaluation of Safe Start Promising Approaches Results Appendix I: Multnomah County, Oregon In Jaycox, L. H., L. J. Hickman, D. Schultz, D. Barnes-Proby, C. M. Setodji, A. Kofner, R. Harris, J. D. Acosta, and T. Francois, National Evaluation of Safe Start Promising Approaches: Assessing Program Outcomes, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, TR-991-1-DOJ, 2011 Sponsored by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention HEA LTH and INFRASTRUCTURE, SAFETY, A N D EN VI R ON MEN T This research was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and was conducted under the auspices of the Safety and Justice Program within RAND Infrastructure, Safety, and Environment and under RAND Health’s Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Program. Library of Congress Control Number: 2011935596 ISBN: 978-0-8330-5822-5 The R AND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. R® is a registered trademark. © Copyright 2011 RAND Corporation Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Copies may not be duplicated for commercial purposes. Unauthorized posting of RAND documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND documents are protected under copyright law. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit the RAND permissions page (http://www.rand.org/publications/ permissions.html). Published 2011 by the RAND Corporation 1776 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 4570 Fifth Avenue, Suite 600, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-2665 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Email: order@rand.org MULTNOMAH COUNTY, OREGON, SAFE START OUTCOMES REPORT ABSTRACT The Multnomah County Safe Start program developed an intervention for young children (birth to 6 years of age) exposed to domestic violence and involved with child welfare services. The program is fully described in National Evaluation of Safe Start Promising Approaches: Assessing Program Implementation (Schultz et al., 2010). The program planned a quasi-experimental trial comparing similar children in the different child welfare offices within Multnomah County. The Safe Start program staff enrolled 43 families in the study, 32 in the intervention group and 11 in the comparison. By the time of the first follow-up assessment, only 11 families remained in the Multnomah County intervention group and five in the comparison group. Because of low overall study participation, enrollment ended about two months early, and follow-up of enrolled families ended about eight months before other sites. At baseline, caregivers reported that children had been exposed to an average of 2.9 types of violence in their lives. Twenty-three percent of caregivers in the overall sample reported child posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in the “significant” range, and 33 percent reported total parenting stress levels in the “clinical” range. Overall, 63 percent of the intervention group families received at least one session with a Multnomah County advocate and received at least one case coordination meeting. Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) was provided to 28 percent of the intervention group families, with an average number of 16 sessions per family. Of the 11 intervention group families in the retained sample at six months, eight (73 percent) received at least one session with a Safe Start advocate, with an average of 23 sessions. Eight families who received case coordination services and three families in the retained sample participated in at least one CPP therapy service. Evaluation of the impact of the intervention was not possible because of a lack of a comparison group to examine difference in outcomes over time. Limited outcome analyses were conducted to examine changes between baseline and the six-month assessment within the intervention group only. In these analyses, no significant changes in outcomes were observed, with the exception of caregiver 1 experience of domestic violence. On this measure, however, a decrease would be expected because the baseline observation period is considerably longer than the six-month window covered by the first follow-up research assessment. Overall, the sample size limitations mean that no conclusions can be drawn about the impact of the Multnomah County Safe Start intervention as implemented on child- and family-level outcomes. However, our process evaluation found that the program model did appear to have important impacts in terms of increasing integration and coordination of services between child welfare and domestic violence advocacy service providers (Schultz et al., 2010). This is a positive finding, as system-level change was a key goal of the program. The intervention model’s impact on individual outcomes, however, remains unknown, and conclusions await testing with an adequate sample size. INTRODUCTION The Multnomah County Safe Start program is located in Multnomah County, Oregon, its most populous county. Safe Start intervention services were provided in Gresham, a city adjacent to Portland. Compared to the rest of the state, Multnomah County reported a higher risk of co-occurring domestic violence exposure among its child abuse cases managed by child welfare services (37 percent in Multnomah County cases relative to 28 percent statewide) (Multnomah County, 2004). The Safe Start program was designed to address a deficiency in coordinated services for the issues of child abuse and domestic violence, as well as poor communication between the two systems that respond these problems (Multnomah County, 2004). Thus, the primary focus of the program was to develop an intervention for young children exposed to domestic violence and involved with child welfare services. According to the Safe Start program’s original Safe Start proposal to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the two targeted service systems operated independently to meet their respective objectives, with child needs being the primary focus of child welfare services and adult victim needs being the main thrust of domestic violence services (Multnomah County, 2004). Consequently, the relationship between child welfare agencies and domestic violence programs has been strained at times, and even sometimes described as incompatible (Aron and Olson, 1997). The Multnomah County program is part of an innovation in 2 thinking about how services should be delivered to children involved in child welfare services who have been exposed to domestic violence. This trend focuses on seeking to integrate the missions and practices of child welfare and domestic services providers such that they would be working together toward joint goals rather than at cross-purposes. An example of prior efforts that influenced the development of the Multnomah County program was developed by the Massachusetts Department of Social Services (Schechter, 1994). This model colocated domestic violence and child welfare services under one roof and prioritized collaborative service provision. Similarly, in the Multnomah County Safe Start intervention, direct services were provided through the coordinated efforts of both the child welfare and domestic violence service systems, with the explicit intention of ameliorating the negative effects of violence exposure on child emotional well-being and the caregiver-child relationship. Thus, the Multnomah County Safe Start project represents a relatively new and creative approach to delivering services to meet the needs of both child welfare–involved children and adult victims of domestic violence. Because of low enrollment and retention in the Multnomah County Safe Start program, the outcomes evaluation detailed here presents descriptive information about baseline observations only. • • • • • • MULTNOMAH COUNTY SAFE START Intervention type: Domestic violence advocacy, CPP, and case coordination and consultation Intervention length: For all components, flexible depending on meeting goals of case plan Intervention setting: In-home and office-based Target population: Children exposed to domestic violence within a county child welfare population Age range: 0–6 Primary referral source: Gresham Branch Office of County Child Welfare Services 3 INTERVENTION The Multnomah County Safe Start program involved three main components: domestic violence advocacy, a modified version of CPP, and case coordination and consultation. For all components, the intervention length varied depending on individual need and case plan. The services were voluntary and offered in addition to usual services and procedures of the Gresham Child Welfare Office. Services were provided at a location most convenient for the client, including in the home. Domestic violence (DV) advocacy was intended to be the primary service. Case coordination and consultation among the DV advocates, child welfare workers, and (when applicable) the CPP provider was also expected for all clients. A modified version of CPP would be offered as an additional service for mothers who expressed an interest in improving their parenting or parent-child relationship. These components are described briefly in the following paragraphs. For a full description of the Multnomah County intervention as it was delivered, see Schultz et al. (2010). The domestic violence advocates were physically located in the Gresham Child Welfare Office to facilitate the identification of cases and to facilitate direct service coordination with child welfare workers. The initial advocacy services involved conducting a domestic violence–focused safety assessment. The advocates also assessed whether the family’s basic needs were being met for such things as food, clothing, housing, and utilities. The advocates then worked with the mother to develop a safety plan and assisted her as needed to meet the basic needs of herself and her children, in collaboration with child welfare. The advocates also offered adult domestic violence victim support groups and provided individual social support, such as accompanying mothers to court hearings. Ultimately, the model expected that domestic violence–specific advocacy services would improve the mother’s life circumstances and functioning, which would in turn improve those of the children. The therapy component involved a modification of the Lieberman and Van Horn model for CPP (Lieberman, Van Horn, and Ghosh Ippen, 2005). In Multnomah County, the CPP was delivered in clients’ homes, where sessions were expected to last 60 to 90 minutes. Using “Don’t Hit My Mommy” (Lieberman and Van Horn, 2005) as a procedural guide, the therapist focused on helping mothers recognize, understand, and respond to the impact of domestic violence on their children and on their own parenting. The intake into the counseling 4 component involved taking information about the family’s domestic violence history; reviewing the mother’s concerns about her parenting, her relationship with her children, and their behaviors; and developing a case plan with the mother setting out goals (tied to the mother’s specific concerns) to work toward over the course of the sessions. The sessions ended when the goals of case plan were achieved. In addition to the direct services provided to families, the Multnomah County Safe Start program provided case coordination services, which included discussions and joint case planning between child welfare workers and domestic violence advocates coordinate services to families they are jointly serving. Case coordination also involved both formal case review meetings (which could include multiple other service providers, such as the parent-child specialist) and informal conversations as the child welfare workers and advocates interacted with one another around the office or stopped by each other’s work spaces to “touch base” about a particular family. Consultation activities, such as crosstraining, technical assistance, and monthly partner meetings, allowed both advocates and child welfare workers to gain a better understanding of each other’s approach to working with individual families, including best practices and legal and agency policy requirements. Efforts to ensure and monitor the quality of the program included the provision of specific training on the intervention, the child welfare system, and implementation plans early in the project. In addition, the domestic violence advocates’ services were monitored through monthly meetings and as-needed consultation with their respective agency supervisors, and the advocates participated in the monthly partner meetings to discuss their service provision overall. The parent-child specialist received clinical supervision once per week through her agency, augmented by once-weekly meetings with her direct supervisor to discuss her services and individual cases. Also, the domestic violence advocates, parent-child specialist, and child welfare workers had prior experience working with victims of domestic violence. 5 METHOD Design Overview The design of this study was a quasi-experimental effectiveness trial comparing children in the Gresham Child Welfare Office with similar children recruited from three other child welfare branch offices within Multnomah County. The treatment group from the Gresham office received domestic violence advocacy, case coordination, and a modified version of CPP. Study enrollees from the comparison branches of county child welfare offices received child welfare case management services and referrals as usual. The planned data collection was to assess child outcomes and contextual information at baseline and at six, 12, 18, and 24 months. As discussed below, however, no assessments could be completed after the six-month mark. Study enrollment took place between January 2007 and March 2009 (over 27 months). Evaluation Eligibility Criteria Eligible domestic violence victims with concurrent child abuse and/or neglect issues in their families were invited to participate in the Safe Start program. Inclusion criteria for Safe Start services were as follows: (1) Current or recent domestic violence issues were identified as a reason for child welfare referral or as a family issue during the subsequent child welfare investigation; (2) the mother (or primary female caregiver) of the children in the case had experienced domestic violence; (3) at least one child in the family was 6 years old or younger; and (4) the family had proficiency in English or Spanish. When more than one child in the eligible age range was eligible for the program by virtue of exposure to violence, the child with the closest birth date to the date of enrollment was selected as the target child for the evaluation. Recruitment of the Treatment and Comparison Groups Because of the child welfare context of the research, recruitment into the study for both the treatment and comparison groups had to proceed in a twostage process. In Oregon, researchers are prohibited from directly contacting families identified in child welfare records. Only authorized personnel within the Oregon Department of Human Services (child welfare) can contact families to ask if they are interested in hearing about research participation. Once this 6 “consent to contact” is obtained, researchers can proceed to approach families about study participation. For treatment group recruitment, the Safe Start Domestic Violence Advocate stationed in the Gresham office was authorized to seek consent to contact from eligible families. In the comparison group offices, however, Safe Start program staff were not available, so designated child welfare personnel filled this role. To identify eligible children for the treatment group, Gresham Protective Services supervisors looked for cases that met study eligibility criteria as part of their standard procedures for reviewing new referrals to the Child Welfare Office. The supervisors would then provide the case information to the Safe Start domestic violence advocate. The advocate would then seek to contact the primary caregiver, explain the available Safe Start services, confirm study eligibility, and introduce the study. For caregivers willing to hear more about potential study participation, contact information was provided to the research team. The research team would then seek to set up a meeting with the caregiver to fully explain the study, obtain consent for participation, and complete the process of enrolling the family in the study. Caregivers could refuse study participation and still receive all Safe Start services. In fact, the program sought to keep confidential from the service providers the identities of the families that did choose to enroll in the study. For the comparison group, an equivalent procedure for identifying potentially eligible cases was not feasible in the comparison child welfare branch offices. Thus, the Safe Start program coordinator was granted access to the electronic case file database used by child welfare offices to document and record information about new and existing cases. On a monthly basis, the Safe Start program coordinator would review all new cases (over the past 30 days) in the database and record information about potentially eligible cases. This case information was then passed to designated child welfare personnel to seek consent to contact from the caregiver. For interested caregivers, contact information would be passed to the research team, which would in turn contact the family to explain the study. Measures The measures used in this study are described fully in Chapter Two of the main document (see http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/ 7 TR991-1.html). The measures were uniform across the national evaluation but prioritized within each site as to the relevance to the intervention under study. Table 1 displays the prioritization of primary and secondary outcome measures for Multnomah County’s intervention. As discussed in the following paragraphs, the enrollment and retention rates were low for this site. Thus, several outcome measures selected by the site could not ultimately be included because the number of children assessed on those measures was inadequate to allow for even descriptive summaries of the measures (i.e., there were fewer than five children in the group). This included the family involvement measure of the caregiverchild relationship domain (selected as a secondary outcome) and both domains selected as tertiary outcomes: (1) the school readiness/performance domain (measured by the Woodcock-Johnson III) and (2) the affective strengths and school functioning measures of the social-emotional competence domain. 8 Table 1 Prioritized Outcome Measures for Multnomah County Safe Start Primary Outcome Measures Domain Source/Measure Age of Child All Respondent Caregiver-Child Relationship Violence Exposure Parenting Stress Index Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire All Caregiver Caregiver Victimization Caregiver Victimization Questionnaire All Caregiver Secondary Outcome Measures Domain Measure Caregiver Age of Child 3–6 years Respondent PTSD Symptoms Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children Behavior/Conduct Problems BITSEA and Behavior Problem Index 1–6 years Caregiver Social-Emotional Competence ASQ 0–2 years Caregiver Social-Emotional Competence BITSEA and SSRS (Assertion and Self-Control) 1–6 years Caregiver Social-Emotional Competence Background and Contextual Factors SSRS (Cooperation) 3–6 years Caregiver All Caregiver Everyday Stressors Index Caregiver NOTE: ASQ = Ages and Stages Questionnaire, BITSEA = Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment, SSRS = Social Skills Rating System. Enrollment and Retention The Multnomah County Safe program sought to recruit eligible families from within a child welfare population. According to data submitted on its Quarterly Activity Reports, Multnomah County Safe Start enrolled 12 percent of the families referred to the program. The most common reasons that families were not enrolled related to legal guardian–related issues, such as inability to locate or obtain permission from the noncustodial parent (61 percent), and caregiver-related issues, such as inability to locate or missed appointments (38 percent). In Table 2, we present the number and percent of all enrollees who were eligible for participation at each data collection time point. At a minimum, a 9 completed caregiver packet is necessary for a family to be included in the outcome analyses. The overall retention rate for the study was 37 percent for caregivers at six months and 29 percent for children. As shown in Table 2, the retention rate was somewhat lower for intervention group caregivers at six months, relative to comparison group caregivers. Specifically, the Multnomah County program staff initially enrolled 32 families in the intervention group and was able to complete a six-month research assessment with 34 percent of caregivers. For the initially enrolled 11 comparison group families, the program retained 45 percent of caregivers at six months. By the 12-month mark, only seven intervention group caregivers were participating in the research assessment and only one comparison group caregiver. Because of low overall study participation, the Multnomah County site stopped enrollment of new families about two months before the end of enrollment for the national evaluation and stopped following enrolled families about eight months before other sites. Difficulties with enrollment and retention had to do with the nature to the target population (a child welfare site), coupled with the study design (recruiting into a no-additional-service comparison group), and limited resources available to supplement data collection (Schultz et al., 2010). It must be noted that the low retention rate increases the potential for biased results in analyses that could be conducted with this sample size. In other words, this degree of attrition may be related to treatment factors that lead to selection bias. For example, if families in more distress are more likely to leave the study at a higher rate, the results can be misleading. 10 Table 2 Retention of Enrollees Eligible to Participate in Assessments at Each Time Point Caregiver Assessment Six 12 18 24 Months Months Months Months Intervention Received 11 Expected* 32 Retention Rate 34% Comparison Received 5 Expected* 11 Retention Rate 45% Overall Retention Rate 37% Six Months Child Assessment 12 18 24 Months Months Months 7 19 2 11 0 5 6 20 4 16 2 10 0 4 37% 18% 0% 30% 25% 20% 0% 1 6 0 2 0 0 1 4 1 4 0 1 0 0 17% 0% 0% 25% 25% 0% 0% 32% 15% 0% 29% 25% 18% 0% * The number of expected caregiver assessments for longer-term assessments differs from the number who entered the study because the field period for collecting data in this study ended in the fall of 2009, before all families entered the window of time for assessments at 12, 18, or 24 months. Special Issues In the Multnomah County Safe Start outcomes evaluation, recruitment and retention of families in a child welfare context was challenging. Many caregivers were difficult to locate, either initially or after enrollment had occurred. Moreover, many located caregivers did not provide their consent to be contacted by the research team. Anecdotally, it appeared that the initial lack of interest was often due to fear or reluctance to participate in anything offered in a child welfare context and to the difficult circumstances faced by many caregivers at the time of the initial child welfare referral. Follow-up assessments were rarely completed with enrolled families because most either could not be located or did not demonstrate continuing interest in participation. These recruitment and retention difficulties were magnified for the comparison group since specialized Safe Start services were not offered along with study participation. For a more indepth discussion, see Schultz et al. (2010). 11 Analysis Plan First, we conducted descriptive analyses to summarize the sample baseline characteristics: age, gender, race or ethnicity, the family income level, and the child’s violence exposure at baseline. We also compared the two groups on primary, secondary, and tertiary outcomes at baseline. Because participants were not randomized to groups, there was an increased likelihood that the groups may differ in some ways. To assess this possibility, we tested for differences in child and caregiver characteristics and outcomes between intervention and comparison group children using t-tests and chi-square tests. While 43 children were enrolled in the Safe Start program at baseline (32 in the intervention and 11 in the comparison group), only 16 children total were retained at the six-month follow-up, and only eight children were retained at 12 months. These sample sizes are too small to allow for any estimation of the effect of the intervention on the participants’ outcomes over time and for examining difference within the intervention group by the amount of services received. Without a comparison group, we were only able to conduct limited analyses. When the sample size allowed, we examined differences between the intervention and comparison groups at baseline using t-tests. We also examined changes within the intervention group between baseline and six months using ttests. Because we could not conduct statistical tests comparing the two groups at the follow-up assessments, these results should be interpreted with caution. Because the participants were not randomly assigned to groups in this study, it was not possible to account for any pre-existing group differences. Even though we conducted just one type of statistical test in these analyses (changes within the intervention group only), we conducted this test multiple times because of the large number of primary and secondary outcome measures. When conducting large numbers of simultaneous hypothesis tests, it is important to account for the possibility that some results will achieve statistical significance simply by chance. The use of a traditional 95-percent confidence interval, for example, will result in one out of 20 comparisons achieving statistical significance as a result of random error. We therefore adjusted for false positives using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Our assessments of statistical significance were based on applying the FDR procedure separately to all of the primary, secondary, and tertiary outcome tests 12 in this report using an FDR of 0.05. The FDR significance level differed for unadjusted difference in difference models because the number of statistical tests varied by outcome type. With the 12 statistical tests conducted for the intervention group on the primary outcomes, this led to adopting a statistical significance cutoff of 0.004. With five secondary outcomes tested, the FDR significance level adopted was 0.01. In the discussion of results, we have also identified nonsignificant trends in the data, defined as those tests resulting in p-values of less than 0.05 but not exceeding the FDR criterion for statistical significance. These trends may suggest a practical difference that would be statistically significant with a larger sample size. By the same token, however, they must be interpreted with caution because we cannot rule out that the difference was due to chance because of the multiple significance tests being conducted. RESULTS Baseline Descriptive Statistics For the descriptive statistics, we provide the characteristics for the full enrolled sample at baseline. As shown in Table 3, the baseline sample was composed of 65 percent female children, with an average age of 3.6 years. The Multnomah County Safe Start site enrolled children between birth and 6 years of age. Children ages 3 to 5 made up 49 percent of all enrolled children, and those 2 and younger represented 42 percent of the overall sample. The children in the sample were predominately Hispanic (40 percent), with white (30 percent) children making up the second largest group. Black children represented 7 percent of the overall sample, and remaining were other race/ethnicity children (23 percent). Many respondents did not provide responses to questions about household income. Of the 23 that did answer, almost 70 percent reported a family income of less than $30,000 per year, with the intervention group having lower family incomes than the comparison group (see Table 3). According to the caregiver reports, children in the baseline sample had been exposed to an average of 2.9 types of violence in their lives prior to the baseline assessment. All but one of the caregivers who completed the assessments were the target child’s mother. As noted in the table, there were no statistical differences for these 13 characteristics between the intervention and comparison groups (where statistical tests could be conducted). In the sample of families retained at six months, the demographics were roughly similar to those at baseline, but with only five families retained in the comparison group, statistical comparisons could not be conducted (data not shown). We also examined the Multnomah County Safe Start sample overall at baseline on two outcomes (PTSD symptoms and caregiver-child relationship) to assess the level of severity on these indexes among families entering the study. As shown in Table 4, at baseline, 23 percent of the full sample reported child PTSD symptoms that fell in the significant range, whereas 73 percent fell in the normal range. In terms of the caregiver-child relationship, 33 percent of the full sample had total stress levels that fell in the clinical range. For the different subscales, 33 percent of the sample had clinical levels of parental distress, 19 percent had clinical levels of parent-child dysfunctional interaction, and 26 percent had clinical levels of difficult child responses. 14 Table 3 Multnomah Safe Start Sample Characteristics for Families in the Baseline Assessment Sample Child Characteristics Age CR Violence Exposure Gender Male Female Race/Ethnicity Hispanic White Black Other Caregiver Characteristics Family Income Level Less than $5,000 $5,000–$10,000 $10,001–$15,000 $15,001–$20,000 $20,001–$30,000 More than $30,000 Relationship to Child Parent-Guardian Other Relationship Combined Intervention Comparison N 43 43 N Mean 3.6 2.9 % N 32 32 N Mean 3.8 2.8 % N 11 11 N Mean 2.9 3.1 % 15 28 34.9 65.1 13 19 40.6 59.4 2 9 18.2 81.8 17 13 3 10 N 39.5 30.2 7.0 23.3 % 15 10 0 7 N 46.9 31.3 0.0 21.9 % 2 3 3 3 N 18.2 27.3 27.3 27.3 % 5 1 4 4 2 7 21.7 4.3 17.4 17.4 8.7 30.4 3 1 3 4 1 3 20.0 6.7 20.0 26.7 6.7 20.0 2 0 1 0 1 4 25.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 50.0 42 1 97.7 2.3 31 1 96.9 3.1 11 0 100.0 0.0 Test for Comparison P-Value 0.18 0.77 0.18 NOTES: CR = Caregiver Report. Percentages may not total 100 percent because of rounding. 15 Table 4 Baseline Assessment Estimates for Multnomah Safe Start Families CR PTSD Symptoms for Ages 3–10 Normal Borderline Significant CR Total Parenting Stress for All Ages Parental Distress—Clinical Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction—Clinical Difficult Child—Clinical Total Stress—Clinical Combined N % N Boys % N Girls % 16 1 5 N 73 5 23 % 5 0 1 N 83 0 17 % 11 1 4 N 69 6 25 % 14 8 33 19 3 2 20 13 11 6 39 21 11 14 26 33 3 4 21 29 8 10 29 36 NOTE: CR = Caregiver Report. Finally, we examined differences between the intervention and comparison group at baseline for the Multnomah County program’s primary and secondary outcomes (see this report’s appendix). Primary outcomes for Multnomah County were child violence exposure, caregiver victimization, and parent-child relationship. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups overall on these measures (see Table A.1, first column). Secondary outcomes included caregiver and child PTSD symptoms, child behavior problems, some aspects of social-emotional competence, caregiver victimization, caregiver resource problems, and caregiver personal problems. Again, no statistical differences were observed at baseline between the two groups on these secondary outcome measures (see Table A.2, first column). Uptake, Dosage, and Process of Care Family-level service data were recorded by the program on the follow-up Family Status Sheet and submitted at six-month intervals following initial enrollment (see Chapter Two of the main document [http://www.rand.org/ pubs/technical_reports/TR991-1.html] for a description). Tables 5a and 5b show the type and amount of services received by the families enrolled in the intervention group. The program contained three central components: advocacy, case coordination, and CPP therapy, but parent support groups were added to the program as a secondary service. Table 5a presents the results for services received for all families who were initially enrolled in the intervention group, regardless of whether they continued 16 to participate in the ongoing research assessment. The data displayed in Table 5a include services received by summing all time points reported by the program, with a maximum of 24 months of service provision. Service data for at least one follow-up wave were available on all 32 initially enrolled intervention group families. As shown in Table 5a, 63 percent of the intervention group families received at least one session with a Multnomah County advocate. While the average was 20 sessions, 45 percent of the full intervention group received ten or fewer sessions. The program reported the reason that advocacy services ended for 14 of the 20 families that received this service. The majority (64 percent) ended because of successful completion, with the remaining ending because the family dropped out or could not otherwise continue (three, 21 percent), or for some other reason (two, 14 percent). Case coordination meetings also took place for 63 percent of the full baseline sample, with an average of eight meetings for families receiving this service. The most common reason that case coordination meetings ended was successful completion (43 percent of 16 families with reported data). Families otherwise discontinued services in 31 percent of cases, with the remaining 25 percent (four of 16) of case coordination meetings ending for other reasons. CPP therapy was provided to 28 percent of the intervention group families, with an average number of 16 sessions for the group. The program reported the reason for therapy sessions ending for five of the nine families receiving this service. In three cases the family dropped out of therapy, with the remaining two families successfully completing the program. Parent support groups were attended by five (16 percent) of the intervention group, with 60 percent of those attending between one and ten group sessions. Of these five participating families, the program reported that three successfully completed the parent support groups, while two families dropped out prior to completion. 17 Table 5a Services Received by Multnomah County Safe Start Intervention Families (Baseline Sample) Service Number with Service 20 Percentage with Service* 63% CPP Therapy 9 28% 1–33 Case Coordination 20 63% 1–53 Parent Support Groups 5 16% 2–20 Advocacy Range 1–129 Distribution 1–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 1–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 1–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 1–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 25% 20% 30% 25% 33% 11% 11% 44% 80% 5% 10% 5% 20% 40% 40% 0% Mean Median 20 12 16 13 8 1 10 8 * The denominator is the 32 intervention group families who were initially enrolled in the intervention group for whom one or more follow-up Family Status Sheets were submitted. NOTE: Percentages may not total 100 percent because of rounding. Table 5b shows the services received by the subgroup of intervention group families who participated in the six-month follow-up research assessment. These are the 11 families included in the intervention group in the outcome analyses sample for the Multnomah County program. Table 5b shows the services they received within the six-month period between baseline and the sixmonth assessment. Eight (73 percent) of the 11 families in the outcome analyses sample received at least one session with a Safe Start advocate, with an average of 23 sessions. The number of sessions received ranged from three to 99, with the majority receiving between 11 and 20 sessions. The program reported that fivw of the eight participating families successfully completed their advocacy services but reported no data on the remainder. Of the eight families who received case coordination services, the majority of cases (80 percent) involved between one and five meetings. The program reported case coordination ending successful for three of the eight families, but they were ended for other reasons in two cases, and no data were reported for the remaining three families. As shown in Table 5b, just three (27 percent) of the 11 analysis group families participated in the CPP therapy service, and the program did not report 18 why therapy services ended, after an average of 13 sessions for families in this group. Two (18 percent) participated in the parent support group service, with both reported to have completed this service. Table 5b Six-Month Services Received by Multnomah County Safe Start Intervention Families (Six-Month Analysis Sample) Service Number with Service 8 Percentage with Service* 73% Range CPP Therapy 3 27% 2–19 Case Coordination 8 73% 1–37 Parent Support Groups 2 18% 9–20 Advocacy 3–99 Distribution 1–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 1–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 1–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 1–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 13% 13% 63% 13% 33% 0% 66% 0% 80% 5% 10% 5% 0% 50% 50% 0% Mean Median 23 13 13 10 8 2 15 9 * The denominator is the 11 intervention group families with a follow-up Family Status Sheet at the six-month assessment point who participated in the six-month research assessment. NOTE: Percentages may not total 100 percent because of rounding. Outcomes Analysis As previously discussed, inadequate data substantially limited the analysis of data for this site. As such, we were not able to conduct any statistical comparisons between groups. Mean differences over time could be tested only for the intervention group and only through the six-month assessment point. Mean Differences over Time Table 6 shows differences over time for the Multnomah County program’s primary outcomes, comparing changes for each individual intervention group family between baseline and six months when the sample size allowed. For primary outcomes, there was one statistically significant difference within the intervention group, with a significant decline in reports of domestic violence for between baseline and six months. This finding is expected, given the different 19 reference period for the baseline and follow-up assessments. Specifically, the baseline assessment asks caregivers about victimization over the prior 12 months, while the follow-up assessments ask about the prior six months. Table 6 also shows a nonsignificant trend toward declines in the child witnessing violence. Likewise, this finding is expected, as these measures compare lifetime exposure at baseline to exposure over a six-month period at the follow-up assessment. Table 7 shows changes over time on Multnomah County’s secondary outcomes for the intervention group, except for measures of child PTSD symptoms and child cooperation, as there were not adequate data to test withinfamily changes. Changes were generally in the direction expected, but for those with adequate sample size none of the differences reached statistical significance. 20 Table 6 Changes in Intervention Group Means for Primary Outcome Variables Between Baseline and Six-Month Assessment Primary Outcome Caregiver-Child Relationship CR Parental Distress for Ages 0–12 CR Parent-Child Dysfunction for Ages 0– 12 CR Difficult Child for Ages 0–12 CR Total Parental Stress for Ages 0–12 Violence Exposure CR Total Child Victimization Experiences for Ages 0–12 CR Child Maltreatment for Ages 0–12 CR Child Assault for Ages 0–12 CR Child Sexual Abuse for Ages 0–12 CR Child Witnessing Violence for Ages 0–12 CR Caregiver Total Number of Traumatic Experiences CR Caregiver Experience of Any Non-DV Traumasb CR Caregiver Experience of Any Domestic Violenceb N WithinFamily Mean Changesa 11 1.45 1.91 11 11 11 2.82 6.18 11 –1.36 11 11 11 –0.27 0.18 –0.09 –1.20 # 10 –0.18 11 –0.09 11 11 a –0.55 * This column reflects within-family mean changes between the baseline and six-month scores for each group separately. * indicates a significant paired t-test of differences over time. b This outcome is a categorical variable, and the unadjusted within-family mean change is a change in proportion. NOTES: CR = Caregiver Report; DV = domestic violence. # indicates a nonsignificant trend in the t-test (p<0.05 but does not meet the FDR correction threshold). Mean change estimates are not shown when the group size is fewer than ten, and comparisons are not shown when the group size is fewer than ten for either group. 21 Table 7 Changes in Intervention Group Means for Secondary Outcome Variables Between Baseline and Six-month Assessment Secondary Outcome Background and Contextual Factors CR Caregiver Resource Problems CR Caregiver Personal Problems Behavior/Conduct Problems CR Child Behavior Problems for Ages 1– 18 Social-Emotional Competence CR Child Assertion for Ages 1–12 CR Child Self-Control for Ages 1–12 N WithinFamily Mean Changesa 11 11 –0.91 0.73 10 0.04 10 10 –0.28 0.15 a This column reflects within-family mean changes between the baseline and six-month scores for each group separately. * indicates a significant paired t-test of differences over time. NOTES: CR = Caregiver Report. Mean change estimates are not shown when the group size is fewer than ten, and comparisons are not shown when the group size is fewer than ten for either group. CONCLUSIONS The Multnomah County Safe Start program involved three main components: domestic violence advocacy, a modified version of CPP, and case coordination and consultation. The planned evaluation was a quasi-experimental trial enrolling similar children in different child welfare offices within Multnomah County. The Safe Start program staff enrolled 43 families in the study, 32 in the intervention group and 11 in the comparison. By the time of the first follow-up assessment, only 11 families remained in the Multnomah County intervention group and five in the comparison group. Consequently, evaluation of the impact of the intervention was not possible because of an inability to compare groups on post-intervention outcomes. Because of low overall study participation, the Multnomah County site stopped enrollment of new families about two months before the end of enrollment for the national evaluation and stopped following enrolled families about eight months before other sites. Difficulties with enrollment and retention had to do with the nature to the target population (a child welfare site), coupled with the study design (recruiting into a no-additional-service comparison group) and limited resources available to supplement data collection. 22 The baseline data suggest that the overall sample had been exposed to an average of 2.9 types of violence in their lives prior to the baseline assessment. Caregivers reported significant PTSD symptoms for 23 percent of children in the overall sample, and 33 percent reported total parenting stress levels in the clinical range. Multnomah County’s tailored approach to services meant that families in the intervention group received different types of services, depending on the circumstances. Overall, 63 percent of the intervention group families received at least one session with a Multnomah County advocate and received at least one case coordination meeting. CPP therapy was provided to 28 percent of the intervention group families, with an average number of 16 sessions for the group. Of the 11 intervention group families in the retained sample at six months, eight (73 percent) received at least one session with a Safe Start advocate, with an average of 23 sessions. Eight families who received case coordination services and three families in the retained sample participated in at least one CPP therapy service. Limited statistical testing was conducted for six-month changes within the intervention group only, but no significant changes in outcomes were observed, with the exception of caregiver experience of domestic violence. This change would be expected, however, because of different reference periods for the baseline and follow-up assessments. Overall, the sample size limitations mean that no conclusions can be drawn about the impact of the Multnomah County Safe Start intervention childand family-level outcomes. However, our process evaluation found that the program model did appear to have important impacts in terms of increasing integration and coordination of services between child welfare and domestic violence advocacy service providers (Schultz et al., 2010). This is a positive finding, as system-level change was a key goal of the program. The intervention model’s impact on individual outcomes, however, remains unknown, and conclusions await testing with an adequate research sample. 23 REFERENCES Aron, L. Y., and K. K. Olson, “Efforts by Child Welfare Agencies to Address Domestic Violence: The Experiences of Five Communities, Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute, 1997. Benjamini, Y., and Y. Hochberg, “Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, Vol. 57, 1995, pp. 289–300. Lieberman, A.F., and P. Van Horn, “Don’t Hit My Mommy!” A Manual for ChildParent Psychotherapy with Young Witnesses of Family Violence, Washington, D.C.: Zero to Three, 2005. Lieberman, A. F., P. Van Horn, and C. Ghosh Ippen, “Toward Evidence-Based Treatment: Child-Parent Psychotherapy with Preschoolers Exposed to Marital Violence,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Vol. 44, 2005, pp. 72–79. Multnomah County, Funding Proposal to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention—CFDA Title: Safe Start: Promising Approaches for Children Exposed to Violence, Multnomah County, Oreg., 2004. Schechter, S., Model Initiatives Linking Domestic Violence and Child Welfare, Iowa City, Ia.: University of Iowa, School of Social Work, prepared for the conference on Domestic Violence and Child Welfare: Integrating Policy and Practice for Families, Racine, Wis., June 8–10, 1994. Schultz, D., L. H. Jaycox, L. J. Hickman, A. Chandra, D. Barnes-Proby, J. Acosta, A. Beckman, T. Francois, and L. Honess-Morealle, National Evaluation of Safe Start Promising Approaches: Assessing Program Implementation, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, TR-750-DOJ, 2010. As of July 17, 2011: http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR750.html 24 MULTNOMAH OUTCOMES APPENDIX 25 Table A.1 Comparison of Means for Primary Outcome Variables over Time Primary Outcome Caregiver-Child Relationship CR Parent Distress for Intervention Ages 0–12 Comparison CR Parent-Child Intervention Dysfunction for Ages 0–12 Comparison CR Difficult Child for Ages Intervention 0–12 Comparison CR Total Parenting Stress Intervention for Ages 0–12 Comparison Violence Exposure CR Total Child Intervention Victimization Experiences Comparison for Ages 0–12 CR Child Maltreatment for Intervention Ages 0–12 Comparison CR Child Assault for Ages Intervention 0–12 Comparison CR Child Sexual Abuse for Intervention Ages 0–12 Comparison CR Child Witnessing Intervention Violence for Ages 0–12 Comparison CR Caregiver Total Intervention Number of Traumatic Comparison Experiences CR Caregiver Experience Intervention of Any Non-DV Trauma Comparison N Baseline Mean Six Months N Mean N 32 11 32 11 32 11 32 11 31.00 29.64 22.56 19.45 29.13 25.64 82.69 74.73 11 5 11 5 11 5 11 5 30.27 27.80 21.18 16.00 28.45 22.60 79.91 66.40 7 1 7 1 7 1 7 1 25.29 32 11 2.84 3.09 11 5 1.73 0.20 7 1 0.71 32 11 32 11 32 10 31 8 32 11 0.72 0.64 0.34 0.45 0.06 0.00 1.65 2.00 0.41 0.18 11 5 11 5 11 5 11 4 11 5 0.64 0.00 0.55 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.55 0.14 0.09 0.20 7 1 7 1 7 1 7 1 7 1 32 11 0.16 0.27 11 5 0.09 0.00 7 1 0.00 26 # 12 Months Mean 19.00 27.14 71.43 0.29 0.00 0.14 0.00 Table A.1—continued Primary Outcome CR Caregiver Experience of Any DV Intervention Comparison N 32 11 Baseline Mean 0.75 0.73 Six Months N Mean 11 0.18 5 0.00 N 7 1 12 Months Mean 0.14 NOTES: CR = Caregiver Report; DV = domestic violence. # indicates nonsignificant trend (p<0.05 and > FDR significance criterion). * indicates statistically significant (p-value<FDR significance criterion). Data are not shown for outcomes when the cell size is fewer than five for the group. Comparisons were not tested when the group size was fewer than ten for either group. 27 Table A.2 Comparison of Means for Secondary Outcome Variables over Time Secondary Outcome Background and Contextual Factors CR Caregiver Resource Intervention Problems Comparison CR Caregiver Personal Intervention Problems Comparison PTSD Symptoms CR Child PTSD Symptoms Intervention for Ages 3–10 Comparison Behavior/Conduct Problems CR Child Behavior Intervention Problems for Ages 1–18 Comparison Social-Emotional Competence CR Child Assertion for Intervention Ages 1–12 Comparison CR Child Self-Control for Intervention Ages 1–12 Comparison CR Child Cooperation for Intervention Ages 3–12 Comparison CR Family Involvement Intervention for Ages 6–12 Comparison N Baseline Mean Six Months N Mean N 32 11 32 11 15.66 16.55 23.44 25.45 11 5 11 5 14.36 14.60 22.18 21.40 7 1 7 1 20 4 38.60 6 1 35.67 3 1 31 9 –0.14 –0.04 10 4 –0.21 7 1 –0.42 31 9 31 9 18 4 5 2 0.07 0.10 0.26 0.11 12.28 10 4 10 4 5 1 2 0 0.01 7 1 7 1 4 1 2 0 0.08 23.20 0.49 11.80 12 Months Mean 15.00 22.71 0.19 NOTES: CR = Caregiver Report. # indicates nonsignificant trend (p<0.05 and > FDR significance criterion). * indicates statistically significant (pvalue<FDR significance criterion). Data are not shown for outcomes when the cell size is fewer than five for the group. Comparisons were not tested when the group size was fewer than ten for either group. 28