Document 12166222

advertisement

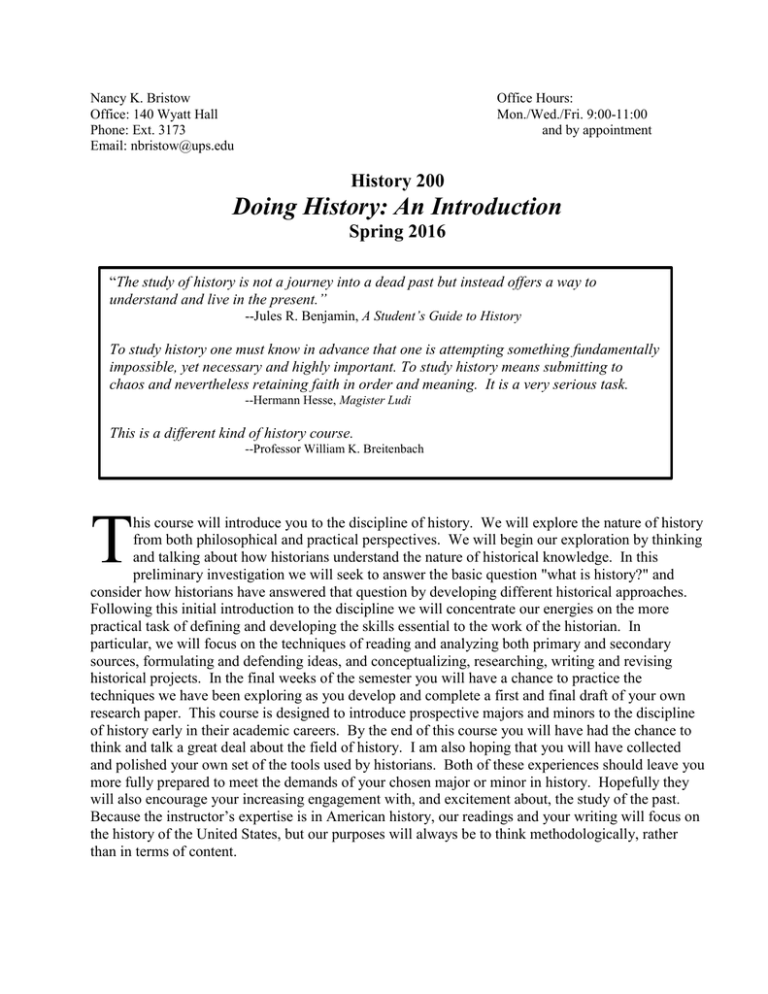

Nancy K. Bristow Office: 140 Wyatt Hall Phone: Ext. 3173 Email: nbristow@ups.edu Office Hours: Mon./Wed./Fri. 9:00-11:00 and by appointment History 200 Doing History: An Introduction Spring 2016 “The study of history is not a journey into a dead past but instead offers a way to understand and live in the present.” --Jules R. Benjamin, A Student’s Guide to History To study history one must know in advance that one is attempting something fundamentally impossible, yet necessary and highly important. To study history means submitting to chaos and nevertheless retaining faith in order and meaning. It is a very serious task. --Hermann Hesse, Magister Ludi This is a different kind of history course. --Professor William K. Breitenbach T his course will introduce you to the discipline of history. We will explore the nature of history from both philosophical and practical perspectives. We will begin our exploration by thinking and talking about how historians understand the nature of historical knowledge. In this preliminary investigation we will seek to answer the basic question "what is history?" and consider how historians have answered that question by developing different historical approaches. Following this initial introduction to the discipline we will concentrate our energies on the more practical task of defining and developing the skills essential to the work of the historian. In particular, we will focus on the techniques of reading and analyzing both primary and secondary sources, formulating and defending ideas, and conceptualizing, researching, writing and revising historical projects. In the final weeks of the semester you will have a chance to practice the techniques we have been exploring as you develop and complete a first and final draft of your own research paper. This course is designed to introduce prospective majors and minors to the discipline of history early in their academic careers. By the end of this course you will have had the chance to think and talk a great deal about the field of history. I am also hoping that you will have collected and polished your own set of the tools used by historians. Both of these experiences should leave you more fully prepared to meet the demands of your chosen major or minor in history. Hopefully they will also encourage your increasing engagement with, and excitement about, the study of the past. Because the instructor’s expertise is in American history, our readings and your writing will focus on the history of the United States, but our purposes will always be to think methodologically, rather than in terms of content. 2 COURSE OBJECTIVES: Students in this course will have the opportunity to: consider critically the discipline of history and its purposes and responsibilities in a democracy gain command over the methods historians use to analyze the wide range of primary texts that are the central building blocks of their work become skilled in evaluating secondary sources and to achieve a growing understanding of the place of historiography in the craft of history to develop familiarity with the kinds of writing assignments that may be required in upperdivision history courses such as close readings, source reviews and research papers to gain skill in conceptualizing issues and questions that can serve as the focus of historical investigations to learn about and practice the process of research that includes locating, assessing, reading and analyzing the sources necessary for a comprehensive exploration of a focused topic to develop their skill in presenting their work to others and in offering effective responses to their peers’ work to continue polishing their skills in cooperative learning READINGS: You will have considerable assigned reading in the early weeks of the course, less in the middle weeks of the course, and very little assigned reading by the final weeks, when you will be conducting and writing up your own research. Readings will be discussed on the day listed in the syllabus. In order to prepare for class, then, you will need to complete the reading assignments before you come to class on that day. You should bring your own copy of the reading with you to class to facilitate your participation in the discussion. In addition to a required COURSE PACKET, the following books are required, and are available at the university bookstore: John A. Arnold, History: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000). Jenny L. Presnell, The Information-Literate Historian: A Guide to Research for History Students (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). Mary Lynn Rampolla, A Pocket Guide to Writing in History (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012). Timothy B. Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2004). WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: You will do a great deal of writing in this course, both preparatory and formal. These assignments are intended to give you a wealth of opportunities to polish the skills this course is designed to teach. Below are brief descriptions of the assignments. Fuller explanations of the formal paper assignments will be distributed and discussed in class at appropriate times. The essay lengths listed below are not limits, but are intended to serve only as guides, giving you a rough idea of the scale of paper I am expecting for each assignment. Your papers in each case may be longer or shorter as needed. 3 Preparatory Exercises: The syllabus provides guidelines for preparation for all class days. I will often ask you to write a paragraph or to complete a worksheet or some other assignment. After you begin your research projects, I will often ask you to bring to class materials related to that work. Some of these preparatory exercises will be turned in. These assignments are described in the syllabus, in bold print, as part of the preparation for the class day on which each is due. You are responsible for being aware of all assignments and for bringing them with you to class on the day they are due. These exercises are important because they offer us an opportunity for individualized communication about the principles and practices of history. You will find that completing them with care will facilitate your successful participation in class discussions as well. Please note, too, that these assignments constitute an important component of your final grade. To reinforce the pedagogical purposes of these exercises, the preparatory exercises must be turned in in class, and on the day they are due, except in cases of illness or emergency. Late assignments will not be accepted. Preparatory Exercises: Due Dates 1. Jan. 22 2. Feb. 3 3. Feb. 5 4. Feb. 12 5. Feb. 26 6. Mar. 7 7. Mar. 9 8. Mar. 25 9. Mar. 30 10. April 4 11. April 11 12. April 13 13. April 25 14. April 27 15. May 4 What is History? Smithsonian Advice Introduction and Body Paragraph, Paper 1 Internal Criticism Form Secondary Source Worksheet on Jacobs Historiography Worksheet “Gutting” Worksheet Notes on Sources Annotated Bibliography Working Hypothesis and Paragraph(s) using 3 “Telling Details” Point-based Outline and 3 Timeline Entries Draft of Introduction Peer-Editing Comments Self-Evaluation Worksheet Revised Introduction or Conclusion Formal Papers: More complete descriptions of each assignment will be distributed in class. Paper #1: What is History? Analyzing Blood Done Sign My Name (3-4 pages) Due in class on Monday, February 8 Paper #2: Using Primary Sources to Build a Paper (3-4 pages) Due in class on Wednesday, February 24 Paper #3: Critiquing History--Secondary Source Review (3-4 pages) Due in class on Friday, March 11 Paper #4: Research Paper--Preliminary Draft (roughly 8-10 pages and 3 digital timeline entries) Due in class on Monday, April 18 Paper #5: Research Paper--Final Draft (roughly 10 pages of text plus 5-10 digital timeline entries) Due in my office (Wyatt 140) by Friday May 13, by 2:00 p.m. 4 Grading Standards for Formal Papers: A paper that receives a grade lower than “C” does not meet the standards of this course. Typically a “D” or “F” paper does not respond adequately to the assignment, is insufficiently developed, is marred by frequent errors, unclear writing, confusing organization, or some combination of these problems. A typical “C” paper has a good grasp of the material on which it is based and adequately responds to the assignment, reflecting a solid understanding, a strong thesis, and meaningful insights. Yet such a paper may provide a less-than-thorough defense of the student’s ideas, or may suffer from problems in presentation such as frequent errors, unclear writing, or confusing organization. A typical “B” paper is very good work that contains significant insights that demonstrate that the student has engaged in serious thinking and has developed an important and imaginative thesis as a result. A “B” paper also includes strong development of the main ideas of the paper, including substantial and wellexplicated evidence. These papers are generally effective in their presentation as well. A typical “A” paper is exceptional. Not only does an “A” paper include all of the strengths of a “B” paper, but it also has an exceptionally perceptive and original central argument that is cogently argued and supported by a very impressively chosen and developed variety of specific examples drawn from a range of sources. An “A” paper also succeeds in suggesting the importance of its subject and of its findings. CLASS PARTICIPATION: In addition to doing significant writing, you will also spend a great deal of time in this course talking about history. While attendance is important in all of your courses, recognize that in this case it is not only mandatory, but also fundamental to your overall success in this course and in other history courses in the future. Because this is a methods course, each class day is devoted to working through a particular skill important to the historian’s work. If you miss a day, you have missed the opportunity to talk and think about a particular component of the historian’s craft. Keep in mind, too, that attendance and contributions to discussions will make up an important part of your grade. You will notice that for almost every day of class there is a "prep" listed in the syllabus. Sometimes this involves doing some informal writing. Other times the preparation simply requires engaging in some careful thinking about questions introduced there. It will be vital to pay attention to these notations in the syllabus. They will help you prepare for the day's class discussion. The following suggestions will also help to make our discussions as fruitful as possible: Prepare for class: This includes not only reading all assignments before class, but thinking about that reading and engaging with the suggested preparation, as well. It is generally useful to write down your responses to the preparatory questions, even if they are not going to be turned in. This not only forces you to think critically about what you are reading but will often make it easier for you to speak up in class. Attend class: Unless you are in class, the rest of us cannot benefit from your ideas, and you will miss the opportunity to benefit from the ideas of your classmates. Participate in discussions: Several minds are always going to be better than just one. For this reason, we will all benefit from this course to the degree that each of you participates in our discussions. Each of you has a great deal to contribute to the class, and each of you should share that potential with the other class members. In this class, too, you have a fundamental role to play as peer editors for your classmates. Listen to your classmates: The best discussions are not wars of words, but are a cooperative effort to understand the issues and questions at hand. Listen to each other, and build on the ideas raised by others. While we will often disagree with one another, you should always be sure to listen to each other. Always treat your classmates, their work, and their opinions with the respect they deserve. 5 Grading Standards for Class Participation: Following each class session I will record a participation mark for each class member for that day’s discussion. It is on the basis of those marks, then, that your participation grade is based. Recognize that absences count essentially as zeroes, and have a profound impact on your participation grade. While illness, emergencies, and obligations on behalf of the university count as excused absences, they can only be recorded in this way if you let me know the reason for your absence. Too many unexcused absences may lead to a student being dropped from the course (WF). A student who receives a grade lower than “C” is consistently unprepared, unwilling to participate, refuses to engage with others, often seems distracted from the discussion, or is too frequently absent. A student who receives a “C” for discussion typically attends every class and listens attentively, but rarely participates in discussion. Other “C” discussants would earn a higher grade, but are too frequently absent from class, or may not listen openly to the ideas and suggestions of others. A student who receives a “B” for his or her participation typically has completed all the reading assignments on time, and makes important contributions to our discussions. This student may tend to wait for others to raise interesting issues, rather than initiating discussion. Other “B” discussants are courteous and articulate but do not listen to other students, offering their ideas without reference to the direction of the discussion. Still others may have a great deal to contribute, but participate only sporadically, or may not regularly connect their contributions to particular texts or specific examples. A student who receives an “A” for his or her participation typically comes to every class with questions and ideas about the readings already in mind. He or she engages other students and the instructor in discussion of their ideas as well as his or her own. This student is under no obligation to change their point of view, yet listens to and respects the opinions of others. This student, in other words, takes part in an exchange of ideas, and does so on a regular basis. This student also makes use of specific texts and examples during the discussion. RESOURCES TO KNOW ABOUT: Office of Accessibility and Accommodations. If you have a physical, psychological, medical or learning disability that may impact your course work, please contact Peggy Perno, Director of the Office of Accessibility and Accommodations, 105 Howarth, 253.879.3395. She will determine with you what accommodations are necessary and appropriate. All information and documentation is confidential. Reference Librarian: Peggy Burge (pburge@pugetsound.edu) is the History Department liaison librarian. You will meet her when she conducts some library sessions for our course. She is also available to meet with you in individual appointments for assistance with your research. You will find she is a remarkably knowledgeable guide to research methods, our library and beyond. Archivist and Special Collections Librarian: Katie Henningsen (khenningsen@pugetsound.edu) is the librarian who handles the university archives. She will have regular office hours as well as open hours at the archives. She, too, is remarkably knowledgeable and a great resource for this course. The Center for Writing, Learning and Teaching is available to all Puget Sound students interested in developing their writing skills. Here you can meet with a writing advisor for help with every stage of the paper process. To make an appointment with a writing advisor you can stop by the center, in Howarth 109, or make an appointment by calling 879-3404 or emailing writing@ups.edu. Harvard University’s Writing Center has a website loaded with useful advice on writing. To visit their site, go to: http://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/strategies-essay-writing. Patrick Rael, Bowdoin College, Reading Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students is a wonderful collection of advice for the history student, available on the Bowdoin College website. The address is: http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/. I will ask you to read materials on this site for some of our class days. 6 POLICIES TO KNOW ABOUT: Academic Integrity: It is assumed that all of you will conform to the rules of academic honesty and integrity. I should warn you that plagiarism and any other form of academic dishonesty will be dealt with severely in this course. Plagiarizing in a paper will be reported to the university, will result in an automatic F on that assignment and potentially in the course, and may lead to more substantial university-level penalties. Because academic dishonesty is such an egregious offense, the penalty is not negotiable. As a member of this academic community, your integrity and honesty are assumed and valued. Our trust in one another is an essential basis for our work together. A breach of this trust is an affront to your colleagues and to the integrity of this institution, and so will be treated harshly. Rest assured that I will make every effort to familiarize you with the rules surrounding academic honesty. If at any time you have questions about these rules, too, know that I am anxious to help clarify them. In the end, though, it will be up to you to know the rules and adhere to them. Illnesses, emergencies, and approved, university-related activities: These are excused absences, provided you inform me about them as soon as possible. Beyond these, though, other absences are unexcused, and will count against your participation grade. In addition, too many unaccounted for absences may lead to your being withdrawn from the course, so please send me an email if your absence falls under an excused circumstance. 48 Hour Rule: Recognizing that life happens, we will operate according to my “48 hour rule” in this course. This means that you can turn in one paper up to 48 hours late without penalty or explanation. Beyond this, though, late papers will be accepted only in cases of illness or emergency, or when prior arrangements have been made, and generally will be penalized except in cases of illness or emergency. You must contact me to make arrangements for any late assignments. The 48 hour rule cannot be used on the first draft of the research project or on preparatory assignments. Course Completion: No late assignments will be accepted after 5:00 p.m. on Friday of final exam week. You must complete all formal papers in order to successfully complete this course. Students missing one of the five formal papers will receive a WF for the course. Bereavement Policy: We all hope this policy will not come into play, but if this should occur, the University of Puget Sound recognizes that a time of bereavement can be difficult. Therefore, the university provides a Student Bereavement Policy for students facing the loss of a family member, which this course follows. Students are normally eligible for, and I would of course grant, three consecutive weekdays of excused absences, without penalty, for the death of a family member, including parent, grandparent, sibling, or persons living in the same household. If you need additional days, you should let me know, and also request additional bereavement leave from the Dean of Students or the Dean’s designee. In the event of the death of another family member or friend not explicitly included within this policy, know that you can petition for grief absence through the Dean of Students’ office for approval, and I am very open to granting it for the course as well. To request bereavement leave, a student must notify the Dean of Students’ office by email, phone, or in person about the death of the family member. If you need any help with this process, please just ask and I will supply whatever support I can. 7 GRADING SCALE: In assigning grades, both during the semester and at its end, I will use the following scale: A+: 97-100 A: 93-96 A-: 90-92 B+: 87-89 B: 83-86 B-: 80-82 C+: 77-79 C: 73-76 C-: 70-72 D+: 67-69 D: 63-66 D-: 60-62 F: below 60 FORMULATION OF COURSE GRADE: Your final grade will be assigned according to the following weighting of the component grades: Paper #1 (due Monday, February 8)………………………….…..5% Paper #2 (due Wednesday, February 24)......………………...….12.5% Paper #3 (due Friday, March 11)............………....…………......12.5% Paper #4 (due Monday, April 18) ………………………….…...15% Paper #5 (due Friday, May 13).............………………………....25% Preparatory writing exercises…………………….……....…......15% Class participation…………………………….……...…………15% Schedule of class meetings, readings, and writing assignments UNIT ONE: WHAT IS HISTORY? * * * * * This unit explores the nature of the discipline of history, forcing us to grapple with its interpretive quality. Historians share methodologies—a way of asking and answering questions—that are distinct to the discipline and on which most historians agree. They also engage, though, in frequent disagreements— over the content of historical interpretations, and even over the nature and purposes of the discipline. Beginning with an historian’s account of his own struggles to understand the past, this unit will give us a chance to develop an understanding of the historian’s work—its goals and its responsibilities. We will learn a bit about the history of history, the evolving assumptions that guide the discipline, and how historians wrestle with the task of knowing the unknowable. 8 “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” --William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun “The past can be used for almost anything you want it to do in the present. We abuse it when we create lies bout the past or write histories that show only one perspective. We can draw our lessons carefully or badly. That does not mean we should not look to history for understanding, support, and help; it does mean that we should do so with care.” --Margaret MacMillan, Dangerous Games “To accept one’s past – one’s history – is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used; it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought.” --James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time 1. (W) January 20 Introduction to the Course and the Historian’s Responsibilities Questionnaire (used for History Department assessment) Why history matters: Holocaust revisionists 2. (F) January 22 What is History? READING: Syllabus for History 200 (seriously, you need to read this front to back! It is our contract and you need to know what it contains and what you are agreeing to.) Mary Rampolla, A Pocket Guide to Writing in History, pp. 1-5 John H. Arnold, History: A Very Short Introduction, ch. 1 Course Packet, pp. 1-22 o Robert C. Williams, “History” o Richard Marius and Melvin E. Page, “Introduction” o Michael J. Galgano et al, “What Is History?” Timothy B. Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name: A True Story, chs. 1-4 PREP: Think a bit about the nature of history. On what identifying features do the historians you read for today agree? Then ask yourselves the following questions: What does it mean to suggest that history is always changing? That history reflects the individual (and the culture) that writes it? What does Arnold mean when he suggests that history “is an argument between the past and the present”? When he refers to history as “true stories”? Next think about the book by Tyson. What is this book about? Why did Tyson decide to write it? What can it tell us about the nature of history as a field? About what makes the work of the historian difficult? What does it suggest about our responsibilities? Write a paragraph answering any one of these questions. Be sure to quote from at least one of our readings in your paragraph. (EXERCISE #1) 9 3. (M) January 25 History: Art or Science? READING: Arnold, History: A Very Short Introduction, chs. 2-3 Course Packet: pp. 23-39 o Carl L. Becker, “Everyman His Own Historian” o Robin G. Collingwood, “The Limits of Historical Knowledge” Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name, chs. 5-7 PREP: Be ready to debate the following question in class: Is history an art or a science? Prepare three reasons in favor of your answer, and three rebuttals to the opposing answer. What are the implications of your answer for how you view Tyson’s work? 4. (W) January 27 History Matters: Sources and Schools READING: Arnold, History: A Short Introduction, chs. 4-5 Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name, chs. 8-9 PREP: What does Arnold mean when he says, “The sources do not `speak for themselves’ and never have done”? When he says, “Every history is provisional, an attempt to say something in the face of impossible complexity”? How do different kinds of history fit into this concept? 5. (F) January 29 The Telling of the Truth and the Problem of Silences READING: Arnold, History: A Short Introduction, chs. 6-7 Moodle: o Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History PREP: Why does Arnold suggest it is important to read sources “against the grain”? When he suggests that “if we ask for one, sole, monolithic Truth, we may silence other possible voices, different histories”? What does Trouillot add to this conversation, and what are the implications of his exploration of silences? 6. (M) February 1 Objectivity, Relativism, and the Complexity of Historical Narrative READING: Moodle: Hayden White, “The Fictions of Factual Representation” PREP: How do you respond to White’s challenge to all historical interpretation? Does Trouillot help us think about this? 7. (W) February 3 The Roles and Responsibilities of the Historian READING: Course Packet, pp. 49-56, 306-311 o Documents on the Enola Gay Controversy o Charles Krauthammer, “History Hijacked” o Martin J. Sherwin, “Forgetting the Bomb: The Assault on History” Moodle: Margaret MacMillan, “History Wars” from Dangerous Games PREP: Write a paragraph (or two) suggesting how the Smithsonian should have handled the Enola Gay controversy and why this would have been the most appropriate resolution. Cite at least one of the course readings to support your argument. (EXERCISE #2) 10 8. (F) February 5 Historical Mindedness, or How Historians Think READING: Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name, complete Course Packet: pp. 44-48, 57-77, 156-161 o Keith C. Barton, “Research on Students’ Historical Thinking and Learning o James J. Sheehan, “How History Can Be a Moral Science” o Samuel S. Wineburg, “Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts” o Conal Furay and Michael J. Salevouris, “Historical-Mindedness: The Goal of o Historical Study” o Michael Harvey, “Paragraphs” Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, ch. 62-65 PREP: Think about what constitutes historical-mindedness. What is the purpose of historical study? What are the key differences, according to Barton, between how students and historians approach historical sources and the past? What does Sheehan suggest about history as a moral pursuit? Why does Wineburg describe our work as an “unnatural act”? Where does “truth” fit in? Given this, how is the way historians approach the past different from how non-historians do so? Now, do you think Timothy Tyson exhibits historical-mindedness in Blood Done Sign My Name? Why or why not? Bring your introduction and one body paragraph of your paper, due Monday, with you to class. We will workshop with these in class today. (EXERCISE #3) UNIT TWO THE RAW MATERIALS: WORKING WITH PRIMARY SOURCES As you know from our first unit, primary sources are the historian’s most important building blocks in their construction of historical interpretations. In this unit you’ll learn how to interrogate primary sources, both recognizing their limitations and discovering the meaning(s) they can offer if read carefully, critically, and “against the grain.” From here we’ll take the next steps, as you take your work with primary sources and build an interpretive essay. “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” --L. P. Hartley, The Go-Between 9. (M) February 8 University Archives and the Thrill of the Hunt **We will meet in the Shelmidine Room on the second floor of Collins Memorial Library. Please note that food, drink, and ink pens are not allowed in the Archives or the Shelmidine Room. READING: No new reading today. Today will be an exciting opportunity to meet both Katie Henningsen, the University Archivist, and Peggy Burge, the Research Liaison for the History Department. We’ll have some fun wrestling “truth” from the raw materials of our university’s history. **Your FIRST PAPER is due in class TODAY!!** 11 10. (W) February 10 The Challenges of Primary Sources: Context READING: Rompalla, A Pocket Guide to Writing in History, pp. 6-15 Course Packet: pp. 86-122 o Documents on the Thomas Jefferson/Sally Hemings controversy o Elsa Barkley Brown, “African American Women’s Quilting” o Conal Furay and Michael J. Salevouris, “Historical Thinking: Context” Moodle: o Visit the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation website and read at least two of the documents posted there related to the Jefferson/Hemings issue. Then read one more scholarly piece posted on Moodle about the issue. PREP: Read through the assigned documents on the Thomas Jefferson/Sally Hemmings controversy, and also read two documents from the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation website and one additional scholarly piece posted on Moodle. Why has it been so difficult for historians to figure out what happened? What do we need to do to avoid these difficulties and develop a responsible interpretation of their historical interactions? To begin answering these questions, read through the essay from Elsa Barkley Brown. What does Brown mean when she discusses the need to “pivot the center”? How do the suggestions of Furay and Salevouris correspond to the ideas offered by Brown? How does all of this frame our approach to the Jefferson/Hemings controversy? Finally, does the evidence confirm that Thomas Jefferson fathered one of Sally Heming’s children? Be ready to explain your answer to this last question. 11. (F) February 12 Finding Meaning: Interrogating our Sources READING: Presnell, The Information-Literate Historian, 221-223 Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, pp. 6-15 (again) and 29-33, 39-42 Handout: Internal Criticism Form History 200 Library Webpage: http://research.pugetsound.edu/History200Bristow Our webpage, created by Peggy Burge, includes significant resources for your research this semester. For today, use the links to subject encyclopedias and dictionaries to read up on the United States in the 1950s. Some useful concepts to explore might include suburbanization, the Cold War, culture, family, atom bomb, baby boom, gender roles, race relations and civil rights. Moodle: The House in the Middle PREP: Using the guidelines on how to read primary sources we talked about in class on Wednesday and the additional material offered from Presnell and Rampolla, “read” the film The House in the Middle. Interrogate the film to gain a full sense of what it intended to say to its audience, where we might find reason to question the veracity of the film, and what unintended insights the source might offer to the student who understands the context of the film and reads it “against the grain.” To be able to do this well, you will want to watch the film, develop a full and meaningful context for it, and then watch it again. Make a record of the three subject encyclopedia entries you found most useful for building context, including a full bibliographic citation for the reference and a sentence suggesting what you learned from it that was useful for thinking about the film. Then fill out the Internal Criticism Form and bring it with you to class. (EXERCISE #4) 12 12. (M) February 15 Case Study: The Little Rock Crisis Introduced READING: Course Packet: pp. 133-151 o William K. Breitenbach, “How to Read a Primary Source” o Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock,” 24 September 1957 o Wayne C. Booth, et al, “Prologue: Assembling a Research Argument” and “Making Good Arguments: An Overview” o William K. Breitenbach, “Internal Criticism Form” PREP: Read the Eisenhower speech and as we did with the film, interrogate it fully, thinking about issues of author, audience, purpose and genre. Be sure, too, to put it into context. Use the same process you did for the film, exploring historical dictionaries and subject encyclopedias (NOT Wikipedia.) Next, begin to imagine topics for which the speech might prove a valuable source. What limitations would constrain its usefulness? Now formulate a question that pushes you to read the source “against the grain”--i.e., a question that makes the document tell you something that Eisenhower did not intend it to reveal. Find a telling detail in the document that could help you answer your question. Again fill out the Internal Criticism Form and bring it with you to class. Today we will imagine how this single source could be used to write an interpretive essay. 13. (W) February 17 Case Study: Asking and Answering Questions about Little Rock READING: Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing, and Researching for History, sect. 3c: “How to Ask Good Questions,” sect. 3d: “What Makes a Question Good?” and sect. 3e: “From Observation to Hypothesis” (http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/) Moodle: o “The Watershed Years of the Southern Movement,” from Freedom on My Mind o Documents on the crisis at Little Rock Central High School at the Eisenhower Presidential Library : http://www.eisenhower.archives.gov/research/online_documents/civil_rights_little_rock.html (Be sure to read the introductory paragraph that precedes the list of sources on the website.) o Also browse the other sites and sources posted on our Moodle site related to the Little Rock Crisis, Eisenhower, and the process of integration in Little Rock PREP: Primary sources do not simply provide us with “the truth,” and instead serve as the basis for historical debates about issues of importance. The Little Rock Central High School crisis offers us one such debate, as historians continue to argue about Eisenhower’s real view on integration and racial justice, and the motivations that moved him to act in 1957. Compare the analysis of Eisenhower’s actions in Little Rock presented by the Presidential Library introduction, and the section from Freedom on My Mind. How do you explain the different perspectives? Now peruse the primary source documents from the Eisenhower Presidential Library. Does one of these documents seem especially useful for making sense of Eisenhower’s actions? What claim would you make about Eisenhower’s views on integration? 13 14. (F) February 19 Imagining Your Papers READING: Course Packet: pp. 152-155 o William Breitenbach, “Writing History Papers” Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, ch. 4 Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing, and Researching for History, ch. 6, “Writing Your Paper,” entire, available at: http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/ PREP: Your second paper will be based in the close analysis of at least three of the documents relating to the Little Rock crisis, integration, or President Eisenhower. It will be up to you to frame a question you can answer with sources available through our Moodle site, to analyze those sources carefully to find “telling details,” and to construct and prove your argument in a paper. Your preliminary work on the paper is your prep for today. Time in class today will be dedicated to building plans for your papers. 15. (M) February 22 Writing Workshop / Peer Editing READING: Course Packet, pp. 295-305 o William Kelleher Storey, “Writing Sentences…” and “Choose Precise Words” PREP: Bring a full draft of your paper to class today. We will begin the day with a brief writing workshop, talking about issues of coherence and clarity, and then break into peer-editing partnerships to apply these principles to the paper drafts. UNIT THREE CONSUMING HISTORY: WORKING WITH SECONDARY SOURCES In this unit you’ll become a participant in the on-going conversation among historians. As you know, historians often disagree. Even working with the same sources and asking similar questions, we may reach different conclusions about their meaning, and the answers they offer to historical questions. In this unit you will learn how to read secondary sources efficiently and effectively, how to recognize their explicit arguments and their implicit assumptions, how to evaluate their quality, and how to discern their historiographical significance. These skills will prepare you for engaging with others about historical issues and questions. You will also learn how to use reviews effectively, and you’ll conclude the unit by writing your own review of a secondary source. “I am aware that there is an inherent tension in suggesting that we should acknowledge our position while taking distance from it, but I find that tension both healthy and pleasant. I guess that, after all, I am perhaps claiming that legacy of intimacy and estrangement.” --Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past 14 16. (W) February 24 Reading Secondary Sources as an Historian: Claims and Evidence READING: Rampolla, A Pocket Guide to Writing in History, 16-26 Presnell, The Information-Literate Historian, ch. 5 Course Packet: pp. 162-164, 360-371 o William Breitenbach, “How to Read a Secondary Source” and “How to Take Reading Notes” o Seth Jacobs, “’No Place to Fight a War’: Laos and the Evolution of U.S. Policy Toward Vietnam, 1954-1963” PREP: Summarize Jacobs’ thesis in one sentence. Then think about how he makes that argument. What are the supporting arguments he employs? What kinds of evidence does he use? Do these seem appropriate for his subject? Can you imagine other ways he could have approached it? **Your SECOND paper is due in class today!! 17. (F) February 26 Secondary Sources: Making Judgments READING: Presnell, The Information-Literate Historian, ch. 10 (skim) Course Packet: p. 360-371 o Seth Jacobs, “’No Place to Fight a War’: Laos and the Evolution of U.S. Policy Toward Vietnam, 1954-1963” Worksheet on Secondary Sources PREP: Read Jacobs again, and complete the worksheet and bring it with you to class. (EXERCISE #5) 18. (M) February 29 Secondary Sources: The Range of the Historian’s Reach READING: Course Packet: pp. 194-225, 312-359, 372-402 o Michael J. Klarman, “Is the Supreme Court Sometimes Irrelevant? Race and the Southern Criminal Justice System in the 1940s” o James H. Meriwether, “`Worth a Lot of Negro Votes’: Black Voters, Africa, and the 1960 Presidential Campaign” o Kim England and Kate Boyer, “Women’s Work: The Feminization and Shifting Meaning of Women’s Work” o Richard H. Immerman, “`Dealing with a Government of Madmen’: Eisenhower…” o K. A. Cuordileone, “`Politics in an Age of Anxiety: Cold War Political Culture…” PREP: Today we want to think about the different kinds of history, the different approaches historians use to make sense of the past. We will divide responsibilities today. Read your two assigned articles. Think about the kinds of questions they are asking, the sources they use to answer their questions, and what these choices tell us about the kind of history the authors are writing. Be ready to report to the class about what you discovered. 15 19. (W) March 2 Reviewing Books and Articles READING: Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, 36-37 Prof. Catherine Lavender, “On Writing Book Reviews,” available at: https://csivc.csi.cuny.edu/history/files/lavender/review.html Course Packet: pp. 226-231 o Steven Stowe, “Thinking about Reviews” Moodle: Reviews of Patrick Hagopian’s The Vietnam War in American Memory o G. Kurt Piehler in Journal of American History o Kirk Savage in Indiana Magazine of History o Robert J. MacMahon in Diplomatic History o Scott Laderman in The Public Historian o Michael Kammen in Reviews in American History PREP: Think about the differences among these book reviews, all written about the same text. How did the audience for each journal shape the reviews? Which did you find most useful? Why? 20. (F) March 4 Library Session #2: Meet in Library 118 READING: Presnell, The Information-Literate Historian, chs. 2-4 PREP: Today’s library session will focus on tools for finding secondary sources, both those we use to begin our research, and those that can take us much more deeply into our subject. We’ll do a fascinating exercise that will also allow you to “see” the concept of historiography. By the end of today’s session you will be ready to locate books and articles on your research interest that can serve as the focus of your upcoming paper assignment, and we will also talk about how to locate book reviews. Today’s reading will make the session productive. You will sign up for individual meetings about your upcoming research projects today. 21. (M) March 7 Thinking Historiographically: Imagining Our Possibilities READING: Three sources you identify. PREP: Today’s class is designed to help you imagine the reach of the historical discipline and the range of ways in which those who practice history pursue their craft. Put another way, we want to think historiographically today. Building on the work we did on Friday looking at the timing and quantity of history written about Japanese American incarceration during World War II, today you you will use the skills you have learned to locate at least three different scholarly articles or books focused on this subject. Skim each of these for approach, source usage, and thesis, and fill out the Historiography Worksheet. When we compile these together in class, we will have a chance to continue our conversation about the different kinds of history, and the particular possibilities of each historiographical lens. (EXERCISE #6) 16 22. (W) March 9 The Historical Conversation: Gutting a Book READING: Moodle: Gutting Worksheet Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing, and Researching for History, sect. 2.c., “Predatory Reading,” available at: http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/ PREP: Your job for today is to locate three monographs focused on topics related to your possible research subject. (Monographs are a study of a focused, single subject, usually written by a single academic historian, and should have either footnotes or endnotes and a bibliography.) To identify some possibilities, follow the instructions from our library session. When you go to the stacks to look at your selections, also browse the books nearby. Pick one book and spend no more than two hours “gutting” it and begin the worksheet. Then locate at least one review of the monograph and compare its perspective with your own and complete the worksheet. Bring the monograph and your completed worksheet with you to class. (EXERCISE #7) 23. (F) March 11 Brainstorming your Projects!! **Your THIRD paper is DUE in class TODAY!!** Enjoy Spring Break! See you in a week! UNIT FOUR DOING HISTORY: THE HISTORIAN AT WORK * * * * * In this unit you will finally be turned loose to “do history” as you complete a research project on a topic of your own choosing (though I will ask that the projects consider a subject in the history of the United States since 1860.) You’ll develop a topic and then research, write, and revise a paper and digital timeline on that topic. We’ll devote time to the research process (use of reference works, electronic databases, bibliographical aids, the use of Summit and inter-library loan); the management of your research materials (note-taking, research logs, avoiding plagiarism); the craft of writing; the creation of a digital timeline using Timeline JS, and the particular aspects of presentation used by historians to communicate (effective use of quotations, proper citation, paper formatting). While you’ll each work independently on your own projects, you’ll work together as peer-advisors and editors. You’ll find that preparation for class will largely be devoted to applying lessons and techniques to your particular project. Even so, there will be much to do outside of class. Success in this unit will require diligence, discipline, and persistence. This unit should prepare you to face the challenges offered by upper-division courses and History 400, the Research Seminar. 17 Let a thousand historical flowers bloom. History is never a closed book or a final verdict. It is forever in the making. --Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., 2007 24. (M) March 21 Getting Started on the Research Project: Strategizing READING: Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, ch. 5 Presnell, The Information-Literate Historian, ch. 1, 6 Course Packet, pp. 248-252, Roy Rosenzweig, “Historical Note-Taking in the Digital Age” PREP: By the time you come to class today you must have some general sense of direction for your research project. To track your process, progress and project, purchase a research log. With your research log at the ready, think about a possible topic. Think about related subjects, events, people that intrigue you. Are there questions here that warrant investigation? Bring this thinking with you to class in the form of an entry in your research log. Today we will also talk about possible methods for organizing your research materials and discoveries. We will also discuss whether there is interest in learning about Zotero, an electronic note-taking system. 25. (W) March 23 Primary Sources and Timelines READING: Presnell, The Information-Literate Historian, review 116-167 and read ch.7 PREP: Today we will spend time with Peggy Burge talking about searching for primary sources for your research projects and about constructing a timeline as one piece of the projects. Today’s reading should allow this to be a largely hands-on process. Before this session, use what you’ve already learned about library research strategy for tertiary and secondary sources, and set out to acquire background information about your possible areas of research. Find and read the best overview of your general topic available in a subject encyclopedia or dictionary. Start by perusing the list on our on course webpage, created by Peggy Burge: http://research.pugetsound.edu/hist200Bristow. Bookmark or make a copy of the most useful entry and bring it with you to today’s session. Also please bring a laptop with you to class. These can be checked out at Tech Services in the library. We will meet in our regular classroom. 26. (F) March 25 Organizing your Research Materials READING: Review Rampolla, pp. 93-94 PREP: Given that your research should be well underway, you need to make a decision about how you will create and manage your research materials. By class time today, figure out how you will manage both your bibliography and your note-taking. Then take notes on any two sources, and bring two copies of your notes for those two sources with you to class. You will work with one set in class, and turn in the other. (EXERCISE #8) 27. (M) March 28 Using Sources Honestly: Academic Integrity and Plagiarism READING: Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, ch. 6 University of Puget Sound Logger, section on “Academic Integrity,” available online at 18 http://www.pugetsound.edu/student-life/personal-safety/student-handbook/academichandbook/academic-integrity/ Course Packet: pp. 253-272 Articles on Ambrose, Goodwin, and plagiarism Moodle: o Joyce Seltzer, “Honest History” and Joanne Meyerowitz, “History’s Ethical Crisis” PREP: Begin by looking over the materials on plagiarism. Make sure you really understand what it is and how to avoid it. Next consider the cases of Stephen Ambrose and Doris Kearns Goodwin. Would they have been found guilty if they had been students on our campus? 28. (W) March 30 Notes and Bibliographies READING: Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, 27-29, 111-144 Moodle: “Annotated Bibliographies,” University of Wisconsin Writing Center, at http://www.wisc.edu/writing/Handbook/AnnotatedBibliography.html PREP: By today you should be able to demonstrate that there will be sufficient primary sources for your research paper. Continue to polish your bibliography, dividing it into primary and secondary sources. Then annotate any three entries. Print up a copy of the bibliography, with the annotations, and bring it with you to class. For an example of an annotated entry, see Rampolla, p. 29. Also look carefully at the difference in format for footnote/endnote citations in comparison to bibliographic formats. We will test our knowledge of citation and bibliography formats in class today! (EXERCISE #9) 29. (F) April 1 Working with the Language of your Sources / Using Evidence Effectively READING: Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, 106-111 Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing and Researching for History, sect. 7.a., “Presenting Primary Sources in Your Paper,” at http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/ PREP: Bring a hard copy of one of your primary sources with you to class today. We will focus both on the close and critical reading of primary sources—reviewing what we talked about weeks ago— and also talk about how to use primary source quotations effectively in a paper. 30. (M) April 4 Working Hypothesis: A Question, a Claim, and Telling Details READING: Review Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, 94-96 Moodle: Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing and Researching for History, sect. 5.c.: “The Thesis” at http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/ PREP: Write out your working hypothesis (a claim) and identify three primary source quotations that support it. Then, write up a paragraph or two using these “telling details” to explain some part of your working hypothesis. (Yes, you are starting to write, even as we will use this exercise to review the effective and correct use and citing of quotations.) Be sure you introduce the quotes effectively, that they fit grammatically, and that all punctuation is correct. Then insert note numbers and include footnotes at the bottom of the page. (EXERCISE #10) 19 31. (W) April 6 Timeline JS Workshop PREP: Today we will meet with Lauren Nicandri to learn about Timeline JS. By today, then, you need to think about the timeline related to your developing project. What are three important dates/events and how might you caption them? What images might accompany them to facilitate a viewer’s understanding? Email this material to yourself before class. LOCATION TBA 32. (F) April 8 Research and Planning Day No Class Meeting Today. I will be attending the Organization of American Historians meeting today. Use your time well; there is much to do! 33. (M) April 11 Formulating and Organizing Your Ideas: The Timeline and the Outline READING: David Kornhaber, Harvard College Writing Center, “Outlining,” at: http://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/outlining Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing and Researching for History, sects. 5.a. “Structuring Your Essay,” at http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/ Course Packet: pp. 283-289 Wayne C. Booth et al, “Drafting Your Report” PREP: Make sure you have completed three timeline entries. With these in mind, formulate and write out your paper’s claim. Underneath it type a “point-based outline” of your argument, as described by Booth. Remember that a “point-based outline” organizes not by topics but by ideas. When you can, make notes about the particular evidence you can use to support the points. In class you will give a two–minute progress report, emphasizing your thesis, key arguments, timeline and best evidence. (EXERCISE #11) 34. (W) April 13 The Introduction and the Conclusion READING: Rampolla, Pocket Guide, review 59-62, 65-67 Course Packet:273-282 Wayne C. Booth et al, “Introductions and Conclusions” PREP: Think carefully about the significance of your research question and your thesis. What is the historiographical context for your work? What is the intellectual problem you are solving? What, in turn, is the contribution your thesis makes to the scholarly conversation? Now think about how you will structure your introduction. With what will you begin? How will you signal the importance of your work? How will you situate your reader? Now write an introduction following the guidelines offered by Booth, and bring two typed copies with you to class. (EXERCISE #12) 35. (F) April 15 Drafting Day: No Class Meeting READING: Review Rampolla, A Pocket Guide, ch. 62-65 Review Course Packet, pp. 156-161 o Harvey, “Paragraphs” Handout: First Draft Checklist 20 PREP: Write, write, write! When you have a complete draft, step back to look at the pieces to make sure they all fit. What is your thesis? Do you announce it in your introduction? Does the introduction also situate your topic and your argument for the reader? Does your conclusion restate the thesis? Are you consistent in the thesis you argue? Does your conclusion also suggest why your findings are important? Finally, be sure that each body paragraph argues a single point, and that that point actually helps you prove your thesis. When all this is in order, review for correctness. 36. (M) April 18 The First Draft: De-Briefing PREP: Be sure to bring THREE COPIES of the completed draft with you to class. You should have a draft of at least 8 pages. Remember that you may NOT use the 48-hour rule on the first draft assignment. You must turn in some form of a draft TODAY IN CLASS. No exceptions. **THREE copies of the FIRST DRAFT of your research paper are due in class TODAY!** 37. (W) April 20 Rest Day Enjoy a day away from class. I’ll be busy reading your drafts! 38. (F) April 22 Preparing for Revisions READING: Rampolla, Pocket Guide, 67-76, 97 Course Packet:290-294 Wayne C. Booth et al, “Revising Your Organization and Argument” Harvard Writing Center, “Revising the Draft”; “Editing the Essay, Part One”; “Editing the Essay, Part Two” at http://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/strategies-essay-writing Self Evaluation Worksheet PREP: Today we will talk about ways to proceed with the revision process. This will allow you to begin the process of revision, even before you receive feedback from your classmates and your professor. Read over the suggestions on how to engage the revision process, including the selfevaluation worksheet, and begin to imagine your next steps. 39. (M) April 25 READING: Workshop with Peer Reviewers 21 The papers of two of your classmates. PREP: For today’s class you will be providing advice for revisions to two of your classmates. Your responsibilities will be outlined in a separate handout that will include clear guidelines for peer-editing. You will spend the first part of class today exchanging ideas about the first drafts. You will need to type up two copies of your comments for the paper you are peer-editing. You will give one copy to the author of each paper, and one copy to me. (EXERCISE #13) 40. (W) April 27 Workday and Individual Meetings: No Class Meeting PREP: By today you need to have made some decisions about your revision work. Using what you have learned from your own work looking at the draft, as well as the comments provided by me and your peer reviewer, fill out the self-evaluation worksheet and bring it with you to your meeting with me. (EXERCISE #14 ) 41. (F) April 29 Writing Workshop READING: Rampolla, Pocket Guide, 69-76 Review Course Packet, pp. 156-161 o Harvey, “Paragraphs” PREP: Carefully revise two pages of your paper, paying close attention to paragraph and sentence structure and word choice. 42. (M) May 2 Workday! No Class Meeting. 43. (W) May 4 Title, Introduction and Conclusion Revisited / History 200 De-Brief READING: Review Course Packet: pp. 273-282 Wayne C. Booth et al, “Introductions and Conclusions” PREP: Go back and look carefully at your introduction and your conclusion. Does your introduction offer historiographical and historical context to situate the reader? Does it announce your paper’s key idea? Does it capture the reader’s interest? Does your conclusion tie your findings to a broader theme or issue? Revise either your introduction or your conclusion and bring a copy of the new version with you to class. (EXERCISE #15 ) Remember: Your FINAL projects are due in my office by 2:00 p.m. on Friday, May 13th 22 Have a GREAT SUMMER!! Classroom Emergency Response Guide Please review university emergency preparedness and response procedures posted at www.pugetsound.edu/emergency/. There is a link on the university home page. Familiarize yourself with hall exit doors and the designated gathering area for your class and laboratory buildings. If building evacuation becomes necessary (e.g. earthquake), meet your instructor at the designated gathering area so she/he can account for your presence. Then wait for further instructions. Do not return to the building or classroom until advised by a university emergency response representative. If confronted by an act of violence, be prepared to make quick decisions to protect your safety. Flee the area by running away from the source of danger if you can safely do so. If this is not possible, shelter in place by securing classroom or lab doors and windows, closing blinds, and turning off room lights. Stay low, away from doors and windows, and as close to the interior hallway walls as possible. Wait for further instructions.