Developing a Strategic Program for Chilean Health Information Technology

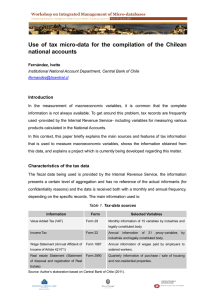

advertisement