Our coasts and seas working today for nature tomorrow Consultation document

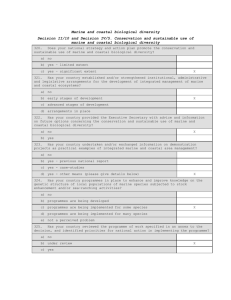

advertisement