Social Network and Financial Literacy among Rural Adolescent Girls: Qualitative

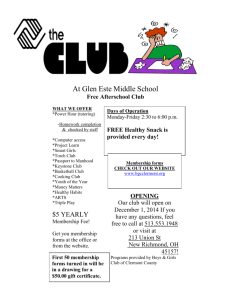

advertisement