Occasional paper CSH / Joël Ruet – VS Saravanan –...

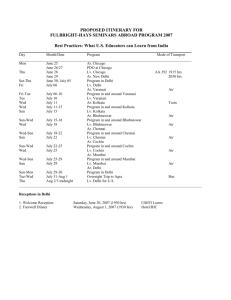

advertisement