CHUTES VERSUS LADDERS: ANCHORING EVENTS AND A PUNCTUATED-EQUILIBRIUM PERSPECTIVE ON SOCIAL EXCHANGE RELATIONSHIPS

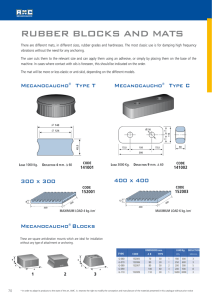

advertisement