Learning to Read at Hillcrest: Executive Summary of the Second-Year... Data for the Hillcrest Reading Program, 2009-2010

advertisement

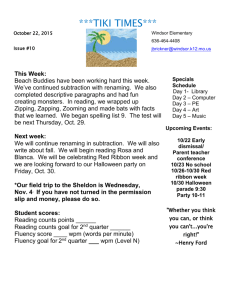

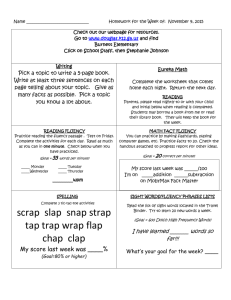

Learning to Read at Hillcrest: Executive Summary of the Second-Year Testing Data for the Hillcrest Reading Program, 2009-2010 Executive Summary Report Prepared by John S. Rice Department of Sociology and Criminology, UNCW Co-Founder of the Hillcrest Reading Program The pages to follow provide a summary of testing results for the children served by the Hillcrest Reading Program Research Team, and our many student tutors, for the 2009-2010 school year. A brief overview of the research and the tutorial program will be helpful to make better sense of the presentation linked above. The research is a straightforward pre-test, post-test experimental design. Following a pilot year in 2008-2009, the second year of the program, September 2009-April 2010 was a conventional experiment as well as an ongoing community intervention. In 2009-2010, we secured two control groups – one at a local elementary school that does not use the same curriculum that we are using at Hillcrest; the other control school uses “Reading Mastery”), the more extensive version of the curriculum that we use (“Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons”); RM also features group instruction versus the one-on-one tutoring that we employ in HRP. Control schools were matched to our participants' characteristics (age, grade in school, race, socio-economic status), in order to make statistical comparisons of outcomes. A Note on Programmatic Differences and Problems Between Years One & Two Year Two’s results must be seen in relation to a combination of mitigating – or, depending on one’s perspective, aggravating – circumstances. The success of the Hillcrest campus, overall, complicated the effective delivery of the reading program in the second year. To be sure, the campus’s success in the Hillcrest community is cause for celebration, insofar as in this, the second year of offering programs to the residents of Hillcrest, the larger Hillcrest campus’s representatives were able to offer a number of other programs, including “Friends, Food, and Fun” (a program designed to teach residents about nutrition and healthy eating habits), as well as cultural enrichment programs in art and dance, and a number of other offerings. Although these many program offerings are, of course, signs of a vibrant and successful remote UNCW campus, they were also provided concurrently with the reading program (4:005:00 p.m., Monday through Thursday afternoons). The concurrence of the programming was, for the reading program’s purposes, a source of difficulty. The “campus” is a single building, approximately the size of a double wide house trailer. Many afternoons this year (2009-2010), unlike last year, in addition to 15-20 kids in the reading program, and a tutor for each of those children, there were simultaneously lots of other people offering and participating in various programs. The influence of so many programs and people proved to have a deleterious effect on the reading program, in short. This influence is, we believe, reflected in somewhat less positive outcomes for our children this year, compared with last year’s results (all of which are posted on 1 the HRP website). Despite a number of successes, the children in the reading program are 4-7 years old, as noted above: they are easily distracted, and easily influenced – as all children are – by older children, adults, and other events occurring as they try to concentrate on their lessons. We were painfully aware of these conflicting interests throughout the past year. On several occasions this year, in fact, the HRP research team members inquired about alternatives: for example, we asked if we could use the large meeting room across the street from the campus (and we did use that space, when it was available, for tutoring), but were told Wilmington Housing Authority policy required that that space must be left available at all times for the Residents’ committee to meet as needed. Frustrated by this ongoing situation, the HRP research team concluded that it might be best to leave the Hillcrest campus. Toward that end, we toured Mary Mosley Performance Learning Center, 4-5 blocks down 13th Street, after being invited – by the principal of Mosley, Mr. Jerry Oates, a friend and former student – to offer the Reading Program at that site. Ultimately, what led us to relent with our wish to move was the children in our program; perhaps especially the children that have been with us for the entire two years. We felt as if we’d be abandoning children and families to whom we’d made a commitment, and with whom we’d forged meaningful relationships. Ultimately, we have agreed to try one more year at the Hillcrest campus, but at an earlier time: we will offer the program in the 2010-2011 academic year at 3:00-4:00 p.m., rather than 4:00-5:00 p.m. We have received assurances, from representatives of the larger Hillcrest campus programming agenda, that the 3:00 time slot will likely prevent us from interfering with the majority of the other programs being offered. Although we are hopeful that such assurances will bear out, we are also continuing to explore other venues (not least because we’ve been encouraged to do so), including Mosley and area churches. Our commitment is to teaching little children to read, and if the Hillcrest campus is not able to provide an environment conducive to that, as we all see it, absolutely essential task, we will have no choice but to find a more suitable environment for accomplishing that task. In 2008-2009, the Hillcrest campus was all but ideal for that purpose; in 2009-2010, circumstances changed substantially – for the purposes of offering multiple programs, for the better; for the purposes of teaching very small children how to read, very much for the worse. Although we are, of course, supportive of programs in nutrition, health, visual arts, and dance, inter alia, given the HRP crew’s deep-seated commitment to doing all that we can to close the educational achievement gap and to helping children to escape poverty, it is essential that we have access to a venue that vouchsafes those aims. If our new Hillcrest campus time slot next year is not conducive to those purposes, those of us on the HRP research team are in complete accord that we will have no choice but to continue our efforts in an alternative location. Results, 2009-2010 In September of 2009, we administered one or two of three quick, and empirically validated, tests of children's reading skills, to determine where they should be placed in the 100 Easy Lessons curriculum. The tests are called DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early 2 Literacy Skills). We tested the children at three time points: as noted, September 2009; we did progress testing in December 2009; and end-of-year testing in April 2010. I will describe the tests in greater detail before summarizing the results for each of the tests. It should also be emphasized that the tutoring did not run uninterrupted from September to April. Given our tutors’ schedules as university students, there was a break in tutoring from December of ’09 until January of ’10; there were also breaks for Thanksgiving, Christmas, and the traditional Spring Break. As such, in the fall semester, the average time each child spent receiving tutoring was, on average, between 9-13 hours; in the spring, the average tutoring time was between 11-15 hours. Older children were given the Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) Test in which children read aloud from a very short story. The children are timed, and after one minute, they read another story, and another. All in all, the test takes about 4 minutes. As they read, the tester follows along on his/her own copy, marking out words the child gets wrong or does not get within three seconds, and marks the point at which time elapsed. o Each test has established benchmarks for the children: for the ORF, they are as follows: Benchmarks for Oral Reading Fluency Test Grade Level Spring of 1 Grade Spring of 2nd Grade Spring of 3rd Grade st Fluency Rate (Words per Minute) 40 WPM 90 WPM 110 WPM 3 Chart 1: Oral Reading Fluency Rate, T1-T3 118 1 110 120 87 100 80 90 84 78 86 41 59 28 60 61 61 53 57 42 24 47 15 40 43 20 24 38 0 3 MW B 2 AP ORF T1 2 FS 2 1 IM JJ ORF T2 ORF T3 40 33 22 0 3 19 35 15 1 XM 12 5 18 1 1 MM TW Net Gain This chart shows the progress of all of the children that participated in the reading program throughout the year. Because some of the children either stopped coming to the program, or joined us later in the year, there are no testing data for some of the participants at one or another of the testing periods. For example, B. did not show up on the days that we did mid-year progress testing; likewise, F.S. was not present when we did baseline testing in September. Given the established DIBELS benchmarks, M.W., the third-grader (far left), who has now been with the program for two years, has in that time gone from being seriously at-risk when he started with us (in September 2008, he scored 19 WPM), to exceeding the benchmark of 110 WPM by spring of third grade. In the same vein, three of our first-graders – J.J., X.M., and T.W. – progressed from being seriously at-risk to meeting and exceeding the benchmarks for their grade level. Respectively, J.J. gained a total of 61 WPM, 21 words above the benchmark for the spring of first grade. X.M. also made solid gains: from 15 to 57 WPM, a net gain of 42 WPM. So too, T.W. went from 18 to 47 WPM, picking up 29 additional WPM over the course of the second year of the program. J.J.’s progress bears special mention. Indeed, her mother told Jess MacDonald, HRP’s Onsite Program Coordinator, that J.J. began the year reading at Level One, 4 the lowest level for her grade; by her third-quarter report card, she was reading at Level Three: the highest level for her grade. Those results are clearly evident in her ORF scores: as already noted, she improved from getting not a single word correct in one minute, during the baseline testing in September, to being able to read sixty-one words correctly in one minute by the time we did April post-testing. Those positive outcomes notwithstanding, we are concerned about the results for one of our first-graders, for all of our second-graders, and for one of our third-graders. M.M., for example, improved by 19 WPM from September through April, but is still 16 WPM behind where he needs to be. The second-graders are all below the desired benchmark reading level – F.S. and I.M., as the chart shows, are, respectively, 31 and 37 WPM behind the skill level they should demonstrate. A.P. is closer to her grade-level benchmark of 90 WPM by the spring of second grade, but she would still have to be considered moderately at risk. For F.S. and I.M., their lower gains are primarily a function of poor attendance. As chart 1 shows, F.S. was not there for the benchmark testing, in September, reflective of his overall pattern of sporadic attendance; the same was true for I.M.: both this year and last, she participated in the program only about half the time. (Thus, we have no mid-year progress data for her.) For B. and M.M., the stories are different. M.M. has always been a reluctant participant in the program. On numerous occasions, the only reason he came to tutoring was because his mother forced him to come. In addition, all year, he – and a couple of the other children – were unduly influenced by a little boy their age, A.N., who does not participate in the reading program, and has consistently proved to be a disruptive presence in and around the Hillcrest campus (A.N. is constantly being reminded, for example, about the larger campus’s policies of respect for others and their property, and for the programs that are run out of the campus. These reminders, however, have little teeth, as there is also a campus policy that no child can be barred from the area.) B., conversely, has major issues with self-confidence. She gets easily frustrated, has quite extreme mood swings, and makes frequent reference to her own perceived lack of intelligence. However, problems with poor attendance, negative self-perception, and A.N.’s disruptive influence, we believe, also overlapped with, and were exacerbated by, the structural problems to which I referred in the introductory remarks. Indeed, all of the individual-level issues have been constants – i.e., they have been issues with which we’ve had to contend since the reading program’s inception. The only new factors affecting tutoring, and the children’s progress with reading skills, in the second year of the program, centered on the multiple new program offerings and the attendant upsurge in crowding and distraction. Thus, again, we are hopeful that the earlier time slot for the program next year will reduce those problems. 5 The younger children were given either (in some cases, both) the Phoneme Segmentation Fluency (PSF) Test or the Nonsense Word Fluency (NWF) Both are one-minute tests, and administration and scoring are the same as is used for ORF (above), with the exception that they receive only a single one-minute test. o NWF is a check to see if children can sound out words they have never seen before (and will never see again); if they can do so, they are developing the phonetic decoding skills necessary to becoming a good reader. The benchmark for this test is 50 Correct Letter Sounds by mid-1st grade. Chart 2: Nonsense Word Fluency, Correct Letter Sounds, T1-T3 110 85 120 102 100 21 16 80 59 60 40 54 43 52 24 53 56 58 34 28 20 37 56 66 17 29 35 47 50 8 6 39 0 6 8 0 8 6 6 0 0 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 AP IM EG JJ XM MM TW NWclsT1 NWclsT2 pre-K pre-k pre-k MM NWclsT3 NM LW Net Gain Chart 2 summarizes the children’s progress on the DIBELS Nonsense Word Fluency tests. A quick contextual note is in order: this year we had a significant influx of pre-k four year olds (there were eight, but many of them rarely attended tutoring, or dropped out, then dropped in), a few of whom were not enrolled in any sort of pre-school program. Consistent with our efforts to not turn any child away from the program, we did what we could with these little ones, despite the obvious fact that most of them had no idea what schooling of any kind actually entails. Their tutors went back and forth between trying to get them do a lesson in 100 Easy Lessons, to holding them in their laps, helping them dry their tears, and so on. (It was, to say the least, an interesting year in this regard.) 6 Given the benchmark of 50 correct letter sounds by mid-first grade, three of our firstgraders were borderline at-risk when we did end-of –year testing in April: M.M., T.W., and E.G. As noted above, on the results for ORF testing, M.M. and T.W. both had some attitudinal issues and also both fell under the sway of A.N., the resident Hillcrest troublemaker. As such, throughout the second half of the year, both of the boys were problematic, as is clearly reflected in their marks on the NWF test: both boys’ scores went down between January and April. The attitudinal and behavioral issues reached their zenith toward the end of April, as exemplified by an interaction between and among T.W., myself, and his tutor. When told that he could not have his end of day pickle because his tutor said he did not do a lesson, T.W. stormed out of the building. He then came back in a few minutes later to try to stare me down. (There is, at minimum, something almost amusing about a little boy that stands about even with my hip, giving me the evil eye.) I told him, “just go on home, T. Tomorrow, when you do a lesson, you can have a pickle.” He want to the door of the center, opened it, turned back to glare at me one more time, then gave me the finger. I said, amazed, “T., did you really just do that?” In reply, he hoisted the finger in my direction once again. We reported this to his grandmother, and forbade him to come back to the program the next day. E.G’s score, although probably also borderline at-risk, given that she scored a 52 not at the mid-point, but towards the end, of first grade is at least hopeful: she nearly doubled her score from September, and her attendance – as partially reflected in her absence for mid-year progress testing – was less than optimal for maximum positive outcome. As for the other first grade children, their success is very notable: X.M.’s performance puts him in good stead, as he more than doubled his mark from September to April, progressing from 29 to 66 correct letter sounds. And, as with her ORF scores, JJ’s progress – from 17 to 102 correct letter sounds – borders on breathtaking! On this, as with all skill measures, JJ’s success both makes us all proud and thankful. She blossomed in the course of the year, and her achievements showed up not only in her dramatic increases in reading skill, but also – and we have seen this in more than one of our children over the past two years – in her self-esteem and in her emerging love of reading. As for our two second-graders, I.M.’s progress is nearly as phenomenal as J.J.’s. After losing ground in the first semester (from 56 to 53 CLS from September to December), she rebounded and got 110 letter sounds correct by April, nearly doubling her September score. Her first semester score reflects, as noted, her erratic participation in the first months of year two. When she is able to attend regularly, as she was in the spring semester, she quickly gained a lot of ground. 7 Chart 3: Nonsense Word Fluency, Words Read Correctly, Time 1 – Time 3 30 27 30 25 20 17 16 20 15 13 19 16 10 3 5 6 7 1 9 2 0 2 IM 5 1 1 EG 1 1 JJ NWwrcT1 XM NWwrcT2 1 MM 1 TW NWwrcT3 A second progress measure for the NWF test is “words read correctly.” Whereas the CLS measure, as discussed in relation to Chart 2, evaluates the number of individual sounds a child identifies in a given nonsense word, WRC measures whether the child correctly identified each sound, and read the entire nonsense word. As chart 3 demonstrates, M.M. and T.W.’s patterns continued: their scores declined from Time 2 to Time 3, commensurate with the decline in positive attitudes and behavior. Likewise, I.M. and J.J.’s notable gains on other measures shows up in the scores, here, as well. J.J. went from 2 WRC in September to 30 in April, whereas I.M. improved from 1 WRC to 27 over the course of the year. E.G. and X.M. also made solid gains, but not so much at J.J. and I.M. (Note: We did not test the pre-k children on this measure.) 8 Chart 4: Phoneme Segmentation Fluency Rate, Time 1-Time 3 62 21 70 60 57 50 10 40 56 68 56 2 52 40 16 28 30 34 35 41 20 10 33 40 46 5 31 12 5 0 2 IM 1 EG 6 1 JJ 1 XM PSFT1 1 MM 1 prek TW PSFT2 0 JJ PSFT3 5 4 17 4 0 prek MM 3 5 0 prek NM 3 0 prek LW Net Gain The PSF test determines whether, and how well, children recognize that words are made up of discrete sounds. The benchmark for this test is 35-45 Correct Letter Sounds (CLS) by spring of kindergarten or fall of 1st grade. As Chart 4 shows, all of the first-graders, except M.M., exceeded the benchmark score for the PSF test by April: E,G. improved by 40 CLS; J.J. by 21; X.M. by 10; and T.W. by 62 – an improvement we had not anticipated for him, given his difficulties in the spring semester. M.M., as noted, maintained his pattern on this measure, as well, going backwards by 19 CLS between January and April. We are concerned about I.M.’s score on this measure, as she is well behind where she ought to be in second grade. In this sense, her solid marks on NWF, given her poorer performance on the Oral Reading Fluency and PSF measures are puzzling, much as is T.W.’s impressive performance on PSF. It may well be that they simply find these specific skill tests more congenial than the others. But their performance bears watching, with an eye towards different tutoring strategies in year three. 9 In sum, it was a very successful second year in the Hillcrest Reading Program. Other than the exceptions noted in the above narrative, all of the children made substantial gains in the fundamental skills that predict whether children will go on to become successful readers. Two or three of the children are still not where they need to be, but the progress they made this year gives them a solid foundation upon which to build further reading skills and to eventually catch up to where they should be. 10