Energy Boomtowns Natural Gas: &

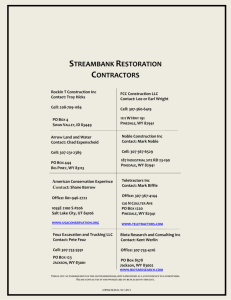

advertisement