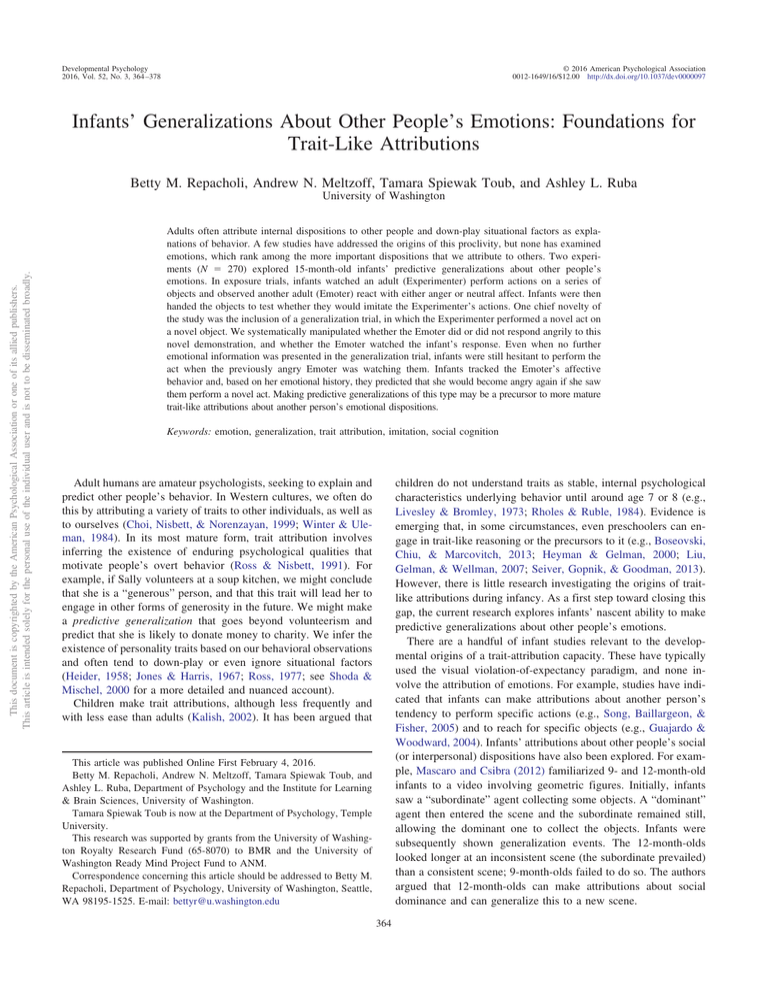

Infants’ Generalizations About Other People’s Emotions: Foundations for Trait-Like Attributions

advertisement