Document 12012461

advertisement

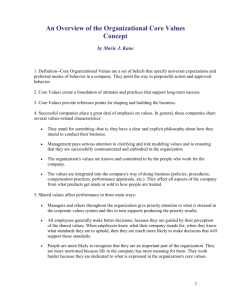

Fiction B ad news usually came through the phone, so Marie was unprepared to receive it in the Walgreen's, face to face with her daughter's landlord. She was waiting in line at the pharmacy counter, where she was picking up three months' worth of medication for herself and Jimmy, her husband. There were at least five pharmacies that were closer to home, but Marie chose this one because she didn't want folks in town knowing her family's business. There was Jimmy's Glucophage and Coumadin and some cholesterol drug (he'd had a minor stroke seven years ago); she was also picking up Atenolol for her bumpy heart, as she called it. Sometimes, the rhythm would shift from its usual light beat to a chaotic tempo that felt like a bag of groceries had split open in her chest and things were tumbling out of the bottom too fast to catch. Today, she would also receive her first bottle of Buproprion, which Dr. Khira had prescribed at her annual physical last week after she'd ticked the box for depression. She'd hoped he'd ask her about her sadness, but instead he'd handed her two weeks' worth of free pills and a pharmaceutical brochure—an effective dodge, she supposed—that enabled physicians to avoid speaking at length to their patients. In essence, he’d handed her a picture book. First there was a fair-haired woman in a gray kitchen, holding her head. Then there was a brilliant yellow pill. Finally, there was the same woman wearing pastels, lipstick, and tossing a ball with two children. Marie had looked at Dr. Khira, ready to speak, but instead smiled a smile that was more a reflex, a simple revelation of teeth, than an expression of her true emotional state. For the smallest of moments, he’d appeared bewildered. Good, Marie had thought. Welcome to the club. Then, because she knew how much doctors valued compliance, she’d put the prescription in her purse. Now, as Marie waited in the interminable line at the pharmacy, she recalled reading that so many people took these drugs traces were present in the drinking water. Why, if the whole world was happier on medication, shouldn't she surrender? She'd taken five days’ worth of the sample pills and noticed, if nothing else, that she felt a bit more awake. "Mrs. Moore, I was just thinking about you!" Wade Thayer, her daughter's landlord in Cedar Grove Apartments, stood beside her wearing a lime green polo shirt with a flashy swordfish embroidered over the chest pocket. He was a big man, tall and thickly built, and Marie was amused to see him pushing a dainty blue plastic cart full of discounted batteries, light bulbs, and cheap plastic children's toy sets. One was a princess set with a tiara, a synthetic blonde ponytail, and a hand mirror. "I stock up after the holidays," he shrugged. "Grandchildren?" asked Marie. "No, no. I like to give out little things now and again to the kids at Cedar Grove when I collect the rent, make repairs." Wade's voice was soothing, deep and mellow as whiskey. She wondered idly what his hands might feel like in her hair, on her waist. Marie felt her shoulders relax. Then, all at once, she realized that Wade was rather handsome, that she was at least twenty years older, and that she hadn't been distracted by another man in so many years she couldn't begin to count them. Wade tilted his head at her, as if he knew what she was thinking. "Hey," he asked, "how's Edna doing these days?" "Enda," Marie gently corrected him. "We gave her my mother’s name. Irish." "Enda, yes. That's nice. Old-fashioned." "We spoke by phone last week. You've got your rent?" "Yes, yes." "She sounded fine. She's doing better." "Well, good." He sounded genuinely pleased. “So, she's working?" "Enda, yes. She's got a little job helping out at the Gulfstream at lunch and dinner. Not waitressing, of course. Sometimes she buses, but mostly she handles the dishwashing. She says she enjoys it." Wade laughed. "I can see that. Don't tell my Julie, but I like doing the dishes, too." Marie offered a smile. She'd never met Julie, Wade's wife. "Well, see, the reason I ask about Enda www.brainchildmag.com 47 Fiction FINDING MARS is that I've been bit worried for her health—since she's taken to wearing that wig." Marie blinked. "Wig?" She felt her throat constrict. Well, you know, when you see a wig or a scarf on a younger woman, you automatically think—well," he lowered his voice, "you know." Marie forced out a breathy little laugh. "I can assure you, Wade, that Enda doesn't have cancer. She's just—Enda. One month she's a redhead; the next she's a blonde. Why not a wig?" She waved her hand through the air and her metal watch unclasped and flew from her wrist. Wade fetched it for her. "May I help the next person in line?" "Good to see you, Wade." The cashier retrieved Marie's prescriptions and rang her out. Several fliers were stapled to the outside of her bag: one page had her name in bold black letters at the top and the word Buproprion, also bold. She folded the bag so no one could read it. Wade Thayer was still lurking around the pharmacy section, leaning on his shopping cart with his tanned, sandyhaired forearms, waiting for her to finish. She'd hoped their conversation was over; now she saw there was more. He motioned her over to the shampoo aisle. "Mrs. Moore, Marie, there's something else. I don't know how to say this; I'm just going to say it. Enda's been in the dumpsters. I've been out twice this week after folks called. See, it distresses the other residents. And, of course, they worry for her, too. Does she have everything she needs?" "What do you mean, in the dumpsters?" "I'm sorry to tell you this. But she's been outside, wearing that wig and rooting through the trash." Marie felt her heart 48 BRAIN, CHILD lurch. "I was out there today and told her she had to stop. She stormed off to her apartment. She took a few bits with her: a child's shoe and a bag from Bullock's Barbecue. I know she's got food; why does she want that? I tried to talk to her, but she won't answer my calls and refuses to open the door. I was going to phone you this evening, but," he spread his hands wide, "then here you were. Here you are. How about that?" "I think you're confusing her with someone else, Wade," she said. "I don't doubt the wig, but dumpster diving? That doesn't sound like Enda at all." “Mrs. Moore--" "Of course, I'll check in with her, just the same. It's been a couple weeks." "Oh, I'm sure that would help." He squeezed her shoulder, his college ring sharp on her collarbone. Marie fled the store but sat for a long while in her parked car. The winters were mild along the North Carolina coast, so unlike her childhood home in Ohio. It was shirtsleeve weather today, in January. Marie ran her hands along the nap of the upholstery until she felt the hairs on her neck settle down, until her eyes ceased to sting. She wished she could open her mouth and bellow her fury at Wade Thayer. He was concerned for his investment, she thought, for his interests—not for Enda. She watched as Wade exited the store with a bit of bounce in his step, his burden offloaded. ... Eighteen months ago, after nearly two decades of what Marie had thought was a sad yet peaceable estrangement common to families, Enda had appeared at their house like a stray animal: dirty, trembling, her long hair tangled and matted so badly that it had to be cut. She'd been living in Memphis, and had been beaten by one of the men she'd dated, though Marie doubted people called it that anymore. The livid bruises that ran from the outside of her wrists to her elbows bloomed huge and alarming, but the ones that made Marie weep were the small faded blue and green fingerprints on Enda's upper arms, along her neck. The bartender where she worked washing dishes had been her salvation: Enda said he'd taken her to the bus station, bought her ticket, packed her food, and gave her his methadone for the long trip home. The fee for Enda’s residential rehab was four times the cost of their first home. At first, Jimmy had refused to pay, arguing that "the girl had to be responsible for her own mess." Marie had to remind him that though Enda was a thirty-seven-year-old woman, she'd never held a job with benefits or insurance. Jimmy relented, though he cashed in Enda's unused college fund to cover the bulk of treatment. "Don’t expect me to keep funding her forever, Marie," he’d warned. "No one," Marie told him, "has asked you to do anything forever." Their conflict regarding Enda calcified. Marie felt, as the rehab center did, that Enda had an illness, a mental illness, in addition to her former substance abuse. Jimmy believed Enda had some "issues" that included malingering and taking advantage of his ability to pay for her needs. Since Enda's return from rehab, she and Jimmy had coiled away from each other, and meaningful conversation ceased. The night Enda arrived back home, Marie dreamt the small skeleton of a bird had lodged beneath her heart. Once awake, the pain knotted in her chest. Marie had no idea what her dream meant, but it reminded her of how, as a young woman, she’d once aspirated a Fiction fishbone at a family reunion. It had stuck in her throat so she could not speak. She couldn’t recall the extrication, but remembered as she’d choked, no one noticed. She’d felt wild with panic, but at the same time, she’d felt embarrassed, afraid she’d ruin the party. legs before coming to where Marie stood. "Hey, there, nasty thing," Marie stroked the cat's silky head. The door to Enda's bedroom was open. Her sheets were huddled in a pile in the center of the bed. It appeared she slept directly on Marie decided to stop by Cedar Grove on her way home from the pharmacy. There were eight apartments in each unit: four on top and four below. Last summer, Wade had installed white plastic rails along the landings that would never need painting. The roof, a patchwork of new and faded shingles from the tropical storms and nor'easters that passed through each year, needed tending. The stairs and landing were covered in Astroturf. Marie pushed the plastic button on Enda's door. A bell chimed inside. She knocked on the door with the heel of her hand. "Enda! It's Mother. Are you here?" Marie didn't know Enda's schedule, except that she usually didn't work until later in the day. Her antipsychotic, if she was taking it, kept her groggy for a couple hours each morning. Marie fished Enda's spare key from her purse but hesitated a few long seconds. She worried that she'd walk in on something she'd rather not see: Enda in bed with a man, drugs, or Enda muttering to herself, the way she did when she was off her meds. Then she thought of Enda in the dumpster and unlocked the apartment. The fierce smell of ammonia met her. Marie had opposed the cat for exactly this reason. Enda barely cleaned up after herself. Cleaning up after the cat was unlikely. "En-da!" she sang, so as not to alarm the girl. "Nomad!" The cat came out from under the sofa and stretched its hind Marie returned to the living room and knelt in front of Enda to catch her eye. For the first time she saw Enda had a small pink duffle bag packed, tucked alongside the sofa. Her red Converse high tops sat beside them. ... the mattress. The apartment, which Marie and Jimmy also funded, was essentially two rooms: a modest bedroom and a living/dining area. A tiny pink-tiled bathroom was located between the two. "Enda?" Marie pushed open the bathroom door. When she flipped on the light, a palmetto bug slipped behind the mirror. The ceiling around the shower was lightly speckled with mildew. There was no sign of a wig. She scooped the litter box, put the waste in a plastic grocery bag, and left. Enda was not at the dumpsters. When Marie tossed in the bag she forced herself to open each bin and look inside, just to be sure. ... She arrived home at dusk. Jimmy stood on the back patio, talking on his cell phone. The brick walls were so thick, reception in the house wasn't possible. She tapped on the glass door but he couldn't hear her. They were both considering hearing aids. Once he was at the right angle to see her, she waved the bags at him so he would know she had returned. Jimmy finished his conversation and she watched as he carried an empty oyster cage to the shed. This season, he planned to restore ten thousand oysters to the cove. He'd built a special shed for this purpose, and there were three chalky mountains of recycled oyster shells on the west side of their property, along with a used Bobcat. Marie removed her watch and rings, set them in the kitchen windowsill, and washed her hands. She took two tuna steaks caught during Jimmy's deep sea weekend last fall along with two ears of corn from the freezer. Jimmy was proud of their thrift; she knew he'd note at dinner that the whole meal had cost them next to nothing. Marie wouldn't point out the $70,000 boat and the thousands of dollars in equipment and fishing gear, all of which Jimmy meticulously maintained. Though they could more than afford it, these were their only luxuries. They carried no credit cards, and no debt. Jimmy managed the money, except for the eleven hundred dollars he deposited each month in Marie's household checking account. Their land, inherited from his people and passed down through generations, had swelled in value from fifty thousand to nearly two million dollars in the last two decades. Their regular investments had increased as well and rivaled their realestate wealth. Even so, they still carefully considered each expenditure, clipped coupons, bought store brands, never travelled. Both had grown up without, as www.brainchildmag.com 49 Fiction FINDING MARS they qualified it. They knew the same fickle wind that raised them up could also demolish them in an instant. Marie poured herself a half glass of whatever white wine had been on sale that week and emptied Jimmy's beer into a frosted mug, just as she'd done nearly each night they dined together during their marriage. These day-to-day routines had once seemed to her like mindless habits. Of late, they'd become the only small comforts she had—those she could rely upon herself to create. Jimmy was sullen during their meal. She expected him to be irritated that she had run late, and had prepared a story about stopping by his mother's grave to replace the plastic flowers. She hadn’t expected him to pout. Then, to Marie's surprise, he apologized. "Time got away from me," he said. "I'm so sorry." He looked genuinely aggrieved. "I didn't mean to make you wait on supper." She was flustered, but touched by the naked emotion on his face. "It's fine. I was late too," she said, hoping he'd ask her why. Then, to fill the silence, she asked how long once he installed the reefs it would take their cover to recover. Jimmy had dredged for decades, so he could moor his boat at home instead of at the marina. Later, the marsh began to die, and their water with it. Forty years ago, they would swim on summer nights, and the water they disturbed would shimmer, silver and alive. Marie remembered it like a romantic film she’d once seen, with someone she could barely recall. ... The next morning, Marie sat on their dock, smoked her morning cigarette, took her pill, and thought about Enda and the wig. Marie decided Enda was concealing something. Perhaps, Marie 50 BRAIN, CHILD thought, Enda had bumped her head. No, more likely she'd badly permed her hair, or dyed it blue—that would be like Enda. Marie figured that if she offered her daughter a trip to the salon, she'd be able to see what was beneath the wig. Jimmy was beside the boat shed, putting on his waders. "I think I'm going to drive into town today," she called out to him. "Help Enda with some shopping. I don't think she works on Thursdays." He sighed. Then, lumbering in his stiff waders like a man slogging through When she first truly understood that Enda would always need their help, Marie had taken a small guilty solace in the situation. She felt her public identity in old age was now clear: to tend her damaged daughter. mud, Jimmy made his way to where Marie sat. "She won't be at work; she doesn't work any day, now." "What are you saying?" "She's been fired, Marie. She hasn't been to work in six days. Six days! She hasn't even been in to get her paycheck. George from the Gulfstream called the other day asking if he should mail it here. She told him she was moving—to Mars!" He waved his hands in the air. "Mars Hill Apartments, maybe?" Marie said. "Enda made it clear to George that flying to Mars was the only way to get away from the terrorists at her apartment complex." Something inside Marie slipped. She felt her body as something beside her, heavy and substantial, yet foreign. "I'm sure there's a reason," Marie said, though she knew better than to hope. "Let's go by there and talk with her." "You talk with her." The lenses of his glasses flashed bright and opaque and his mouth trembled. The combined effect made it appear that he was weeping, but his voice was quiet, as it was when he was enraged but trying to maintain control. "When you do, you tell her she pays her way now. There will be no more money." "Oh, Jimmy." "You can't save her, Marie. Give her money and this will just keep happening." "What will she—" "She'll be forced to figure it out, just like the rest of the world." "She can't. It's not a choice for her." "Of course it's a choice; give the child some credit. You want to give her money? Then get yourself a job and give her all your money—she'll get no more from me. Jesus, I knew you'd get sucked in again. That's why I didn't tell you last week." She felt herself return to her body, only now it felt like a trap. "You knew she was in trouble last week?" Her voice emerged thin and squeezed. Jimmy reddened in his fury. "Marie—" "Come with me today, please," she whispered, "Come look at your daughter." Jimmy took a breath and shook his head. "The best thing that could happen—for her, for you, for me—would be that she just—goes away." Marie’s chest burned, as if her breath had been knocked from her. "Please." "I can’t,” he said, and gripped his forehead. "It’s so much worse when she’s in our lives." Marie stifled a flash of rage and turned away. "We will never stop Fiction being heartbroken," he continued. "Don’t you see? That’s our forever. I just want some peace. We’ve only ever known that when she’s gone. I’m so tired, Marie." Marie gripped her knees to her chest. The oily smell of the marsh was on the breeze. She stared out at the cove. A gull on the dock flipped its head back, unhinged its red maw, and gave a tinny laugh. "What kind of person says that, Jimmy?" "I want our lives back. If that means she goes away, and we never see her again, well, I can find a way live with that." Marie knew this was true. But since Enda's return, Marie had not wished to return to the peaceful life Jimmy thought he had lost. What she longed for was her daughter's return to health. Marie stood to face him. "I'm leaving now to see Enda. She'll need her rent and allowance money." "I won’t be taken advantage of any longer," said Jimmy. "Maybe you can afford to fly to Mars with her, but I can't." Marie started back to the house, but he tried to catch her hand. "Don't you dare touch me," she growled. Jimmy shook his head, and then walked into the fifty-degree water, nearly to his chest, to retrieve his oyster trays. ... When she first truly understood that Enda would always need their help, Marie had taken a small guilty solace in the situation. She felt her public identity in old age was now clear: to tend her damaged daughter. But she hadn't been prepared for how the antipsychotics left her beautiful, red-haired daughter fat and lethargic. It was no wonder Enda hated taking them. Now this business with the wig, and picking through the trash! Marie just wanted it all to stop, for Enda to come to her senses, return to work at the Gulfstream, and need a reasonable bit of help to get by—the occasional run to the grocer's or doctor's. Yet each crisis further eroded Enda's ability to function. She never fully bounced back. Marie knew Enda's only hope was to stabilize, as one of the rehab counselors said. When Enda was in rehab, Marie thought stability would arrive when Enda stopped taking street drugs. Marie now understood the counselor meant that Enda’s mental illness had to stabilize as well, and that had proven tricky to diagnose and treat. Enda's psychiatric diagnoses, from four separate cities, listed her alternately as schizoaffective, manic, suffering PTSD and, in the notes from the twenty-bed backwater hospital in rural Oklahoma, simply "exhausted" and "emotionally labile." The counselor at the rehab center said that, though she'd shown symptoms of a variety of psychiatric conditions at different times, a formal diagnosis mattered little. The bottom line was that Enda was periodically psychotic--with or without crack, or meth, or heroin—but the street drugs made her psychosis exponentially worse. Still, Enda had managed to stay clean, live alone, work, and consistently take her psychiatric medication for six months, allowing something like a normal rhythm to return to her days. ... Before Marie started the car to go to Enda's, she called Bella's salon and made two hair appointments. Then she looked in her wallet. Sixty-seven dollars in cash, one BP gas card, and her household allowance checkbook which, because it was the fourth week in the month, held a mere $229.40. Enda was going to need money if she was indeed moving to Mars Hill, and more than she had here. Perhaps Jimmy was right. How much were they expected to give? For how long? As Marie drove, she came to the conclusion that Enda simply had to contribute more. Maybe, she thought, if Enda had more obligations, more hours than she’d had at the Gulfstream, she'd do better. Once Jimmy saw the girl was doing that, Marie thought he'd soften about continuing to help her financially. When Marie pulled in to Enda's apartment complex, she was ready to do battle with her to keep her safe and where she belonged. Wade's truck was there. Marie hoped that she could get in and out without speaking with him. She was halfway to Enda's apartment when a sheriff's car pulled into the lot. Marie saw now, down the landing, that Enda's door was open. A current of panic surged through her body. Wade emerged from Enda's apartment. Marie heard a noise like shouting. "Thank God you're here, Mrs. Moore. I talked to your husband yesterday evening, after all this happened. I told him she couldn't stay. She can't stay, Mrs. Moore. Not like this." Marie heard glass breaking, then music. She ignored Wade and walked into the apartment. The television was on full blast. Enda, however, was sitting quietly on the sofa, wearing a pink t-shirt stretched too tightly across her bosom. Perched atop her head like a coonskin cap was the pale blond wig. Enda didn't look up. Nomad was curled on her chest, aggressively purring. Marie took the remote and muted the volume. Fern, Enda's county social worker, a tiny slip of a woman, came out of the kitchen with a steaming mug and set it on the table. She patted Marie's arm, then went to greet the sheriff. "Enda, honey," said Marie "what's going on? "I can't talk with them here," Enda www.brainchildmag.com 51 Fiction FINDING MARS whispered, and looked to the door where Wade, the sheriff, and Fern had gathered. Marie marched to the door to close it, but Fern quickly stepped inside. She looked minuscule compared to the men, and Marie understood that was why Fern always wore lumpy sweaters and coats— to give her the appearance of bulk. "Give us a minute, gentleman," said Fern. Then she closed the door and locked it. "Thank you for that," said Marie. "Mrs. Moore, she's refusing the hospital right now. There's a women's shelter nearby that can take her, but she's not interested. It may be too late, it usually fills by noon. Maybe you could convince her to go home with you? Until I can locate other housing?" "I don't understand. So what if she's been in the dumpsters! Is that grounds for eviction?" Fern's eyes grew wide behind her glasses. "I don't know anything about that, Mrs. Moore. Off the record, I was called because she has been harassing the neighbors. She thinks they are all with Al Qaeda. She's been leaving them notes. Yesterday evening she was involved in an altercation. No one is pressing charges, but—" "I know them from before," Enda said thickly. "They look different, but they are spying on us." Marie lowered her voice. "You know her father won't have her at home. Maybe a hotel?” "Mrs. Moore, I think that's not very likely in her state." "Well, I could book her room. I guess I could stay with her, if she needs it." After Marie heard herself, she felt ashamed of her reticence. "I mean, if she'll let me." "I have a friend on Mars who escaped Al Qaeda. I'm going to live there too." "Oh, stop it!" Marie yelled at Enda. "You are not going to Mars! That's your 52 BRAIN, CHILD illness talking." Fern rested her hand on Marie's arm. "Mars is the homeless encampment—it's what people call the camp." "I thought you said she was refusing shelter." Marie followed Fern to the kitchen. "Mrs. Moore, Mars isn't shelter. It's just a wooded area, where the people camp. It's—" "Oh my God. Why can't you take her to the hospital?" "She's not a danger—to herself or anyone, really. Even temporary commit- "Mrs. Moore, she's refusing the hospital right now. There's a women's shelter nearby that can take her, but she's not interested. It may be too late, it usually fills by noon. Maybe you could convince her to go home with you? Until I can locate other housing?" ment—it’s complicated. We can only intervene under certain circumstances. Choosing to be homeless isn't one of them. Arguing with the neighbors isn't either." "But she's delusional." "Maybe so. Even if she is delusional, that's not grounds enough for emergency commitment." "If you can't help, why are you here? What earthly good are you?" Fern’s eyes reddened at the jab. "I'm her caseworker." "I'm her mother!" Marie laughed. "This is absurd." Marie understood Fern had compassion but no power. Right now, that made her useless. Marie returned to the living room and knelt in front of Enda to catch her eye. For the first time she saw Enda had a small pink duffle bag packed, tucked alongside the sofa. Her red Converse high tops sat beside them. "Enda," she said mildly, careful not to let her tone upset the girl, "when are you leaving?" Enda shrugged. "I'd like to get you a couple things, honey. Can you wait a while?" "Mr. Thayer is threatening to evict her today at noon, Mrs. Moore." "No. That's not going to happen," Marie kept looking at her daughter. "He can't evict her on such short notice. It's not legal." "It's easier than you might imagine. Especially with her recent behavior. " "I told him I am going," Enda said. "I was going before he told me I should leave. I'm just saying good-bye to Nomad." Marie looked at her watch—it was 10:15. "Fern, you tell them if they so much as talk to her or make a move to put her on the street, I'll—" Marie cast about for a viable threat. "Why, I'll sue them blind," she said, aware she sounded more like a television actress than herself. "Enda, Mother is just going out to get you a few things. You wait here. Promise me." Enda nodded. Her head was bowed, her fat bottom lip jutted out the same way it had when she was six years old and headed to her first day of kindergarten. "Now, tell me where Mars is, exactly." ... Marie was surprised how close the encampment was—to nearly everything. Her favorite Italian restaurant and her Fiction dental office were less than a mile away. So was Enda's apartment, as the crow flies. To get to Mars, Marie simply parked at Sandy Creek Shopping Center, the upscale shopping mall. There, she crossed a large weedy lot behind the new sixteen-screen cinema and traveled a mere hundred yards down a narrow beaten path through the trash pines. She'd envisioned Mars as a state park, but it wasn't like that at all. There were tents, some with filthy carpet remnants draped on top, some with blue tarp. The stakes were rusted. A few had clotheslines strung between trees. She walked lightly, fearful of surprising someone. She'd left her purse in the trunk, but her jewelry was still on. She twisted her rings around to conceal the stones, as if that would prevent her from harm. "Hello?" she called. "I'm a friend of Fern's. Is there anyone here?" Marie counted twelve tents, some in such a state of disrepair, torn and moldy, that they couldn't be occupied. One however, had affixed a small cedar wreath to the entrance. A fire area was in a small clearing, and there were sooty melted plastic bottles in the center. Then Marie heard a rustling in the leaves, and she spooked, hurrying back along the path, her mouth dry. Her foot snagged on a fallen branch. "Hey, lady. Lady!" A young boy ran up to her, from the direction of the camp. He wore blue jeans and a puffy brown jacket. "You're a friend of Fern's? Did she send you with the tickets?" "What? No. I'm sorry, I don't know anything about tickets." "Oh." Marie noticed the child looked rumpled, and had a large cowlick on the side of his head, as if he'd been napping. "Do you live here, young man? How old are you? Ten?" The boy licked his lips, which were badly chapped. His mouth had a livid red ring around it. "Why are you here?" he asked. His face, despite its youth, hardened as he studied her. "I—well, I know someone who wants to live here." "No one's supposed to know." "What? That you're here?" "My mom and dad will be home soon. We didn't have school today." "OK," said Marie. She scanned the woods. Was someone waiting to grab her? Was this just a set up? "They'll be back from work around five. My mom works right there." He pointed to Sandy Creek Mall. "Bill, my stepdad, he installs carpet. His boss has a white Silverado with heated seats." "Do you need anything?" Marie asked. "Do you want me to ask Fern about the tickets?" "No! Please don't tell her you saw me. I'm allowed to. Sometimes they let me stay here with them. Please don't tell. I don't want to live with my aunt." "Do you like it here?" Marie asked, then immediately regretted it. What sort of answer did she expect? The boy dragged his foot through the pine needles. "Don't tell Fern. But if she gives you the tickets, you bring them back, OK?" Marie was breathless by the time she got back to her car. She dialed Jimmy. When he didn't answer, she left him a long message. She could understand his desire for Enda to disappear from his life, but she felt certain he wouldn't want this. Within minutes Jimmy texted her. His message read: Let her go. For a few long seconds, the world around her seemed to blur and melt. Marie thought she’d go mad. But she didn't. Instead, her thoughts quickly focused. There was no way that Enda could move to Mars with only her pink duffle bag. Where would she sleep? Then Marie saw it: Sportsman’s Paradise. In a mere fifteen minutes, Marie bought a camp cook set, bottles, plates, two weeks’ worth of freeze-dried food, a tent, sleeping bag, sleeping mat, and wet wipes. Marie studied the scruffy bearded salesman. Was he homeless?, she wondered. He recommended fuel for the stove, ecofriendly toilet paper, and a rain poncho. He opened and packed everything for her in the oversized backpack, and attached the bedroll below. She wrote him a check for $876.23. It would be days before it bounced. Marie felt Enda would be OK for a few days or longer. Jimmy could be persuaded. Yet, as Marie rushed back to Cedar Grove, with the backpack in the trunk, she wondered if any action by Jimmy could truly alter Enda’s course. She was refusing shelter and medical help because she couldn’t think clearly. And she wouldn’t be able to think clearly without treatment. Enda stood in the parking lot of Cedar Grove, her small pink duffle bag tucked under her arm like a football, when Marie returned. Wade and the sheriff were gone, but Fern remained. "They left when Enda said she was vacating anyway," Fern said. "That way Wade isn't formally evicting her." "Fern is taking Nomad while I'm gone. Don't worry, Mom." Enda wrapped Marie in her arms. and leaned her whole heavy body against Marie. "Fern knows how to take care of pets." Marie buried her face in Enda’s neck. Her daughter smelled of cigarettes and grape bubblegum. Enda rocked her side to side, and the blond wig slid between them. www.brainchildmag.com 53 Fiction FINDING MARS Marie reached up and cupped her daughter's head. Beneath the wig there was no bad perm or dye job, and no head injury. The only thing it had covered was her daughter's disheveled hair. Her baby girl's hair, graying. "Enda, honey, wait. I've got something for you." Marie took the backpack out of the trunk. "I bought everything you'll need for Mars. Cookware, a sleeping bag, there's a small coffeemaker, and bags of freeze-dried dinners. Turkey tetrazzini, mac and cheese." Enda started walking toward the field just across the way. Marie dumped the backpack on the landing and walked beside her daughter. "Enda, let's go stay at a hotel. It will be fun." "I'm going to Mars. Once I'm there, I'll send a message." "Please, take the backpack." "Mom, no!" yelled Enda. Then she stumbled, and kicked a soda bottle from her path. “God!” Marie quaked with fear. She’d never felt so forlorn. Right then she remembered how she used to nurse Enda to sleep when she was first born. How Marie had marveled at her baby’s tender arms, her glossy red mouth, and fat auburn curls. Enda had been born in the spring, when pollen hung thick on the pines and the air smelled fresh and green. Those early days with her baby, 54 BRAIN, CHILD Marie had felt whole, complete in the world. Never had there been another time like that. Fern gently approached. "I'll check on her, Mrs. Moore. Most times this is a temporary situation.” "What happens now?" Marie whispered. "I go down to Mars each week, Fern said. There's a sandwich shop near the mall where people go at the end of the day. The manager hands out food. He's not supposed to, but he's kind. Sometimes people agree to the hospital or shelter after a while on the street. Enda's been briefly homeless before. In Oklahoma. This isn't new to her." Homeless. Marie hadn't known. Marie looked at the backpack, that massive bundle she'd discarded on the stoop, and sat down beside it. Then came the tears. Her sobs felt torn from her, but there were fewer than she expected. When, at last, she was done, Marie positioned herself in front of the backpack, slid her arms through the straps, and clipped the harness around her chest. Then she pulled herself to her feet and trudged across the field toward her daughter's dimming shape.