Ecotonal Dynamics of the Invasion of Thomas A. Eddy

advertisement

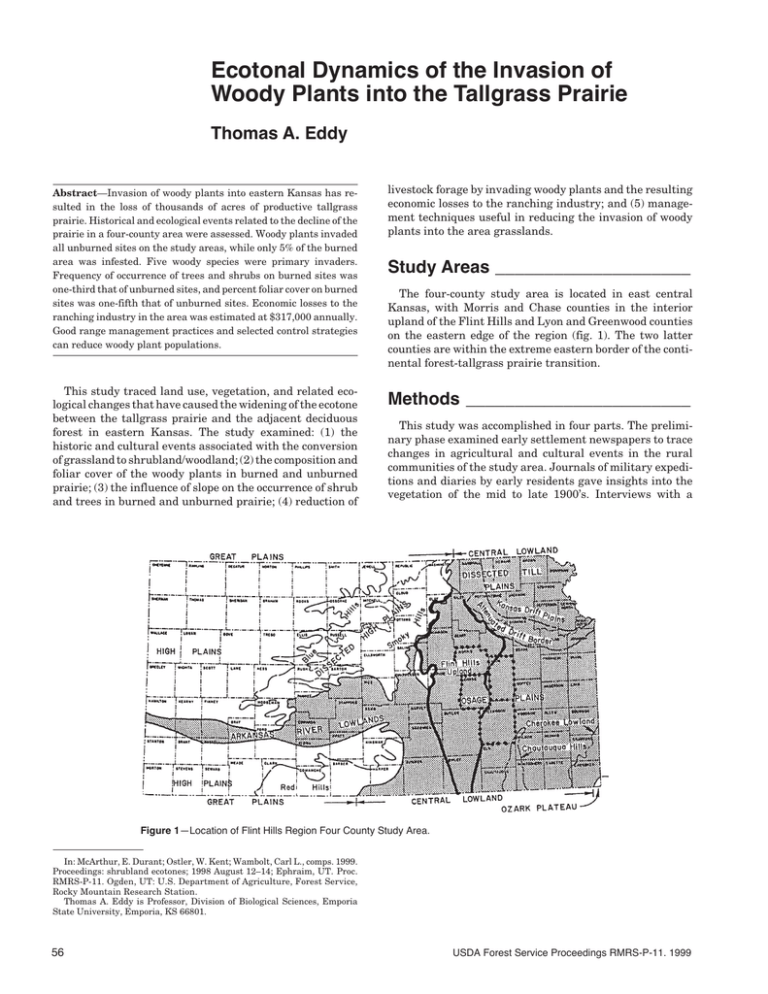

Ecotonal Dynamics of the Invasion of Woody Plants into the Tallgrass Prairie Thomas A. Eddy Abstract—Invasion of woody plants into eastern Kansas has resulted in the loss of thousands of acres of productive tallgrass prairie. Historical and ecological events related to the decline of the prairie in a four-county area were assessed. Woody plants invaded all unburned sites on the study areas, while only 5% of the burned area was infested. Five woody species were primary invaders. Frequency of occurrence of trees and shrubs on burned sites was one-third that of unburned sites, and percent foliar cover on burned sites was one-fifth that of unburned sites. Economic losses to the ranching industry in the area was estimated at $317,000 annually. Good range management practices and selected control strategies can reduce woody plant populations. This study traced land use, vegetation, and related ecological changes that have caused the widening of the ecotone between the tallgrass prairie and the adjacent deciduous forest in eastern Kansas. The study examined: (1) the historic and cultural events associated with the conversion of grassland to shrubland/woodland; (2) the composition and foliar cover of the woody plants in burned and unburned prairie; (3) the influence of slope on the occurrence of shrub and trees in burned and unburned prairie; (4) reduction of livestock forage by invading woody plants and the resulting economic losses to the ranching industry; and (5) management techniques useful in reducing the invasion of woody plants into the area grasslands. Study Areas ____________________ The four-county study area is located in east central Kansas, with Morris and Chase counties in the interior upland of the Flint Hills and Lyon and Greenwood counties on the eastern edge of the region (fig. 1). The two latter counties are within the extreme eastern border of the continental forest-tallgrass prairie transition. Methods _______________________ This study was accomplished in four parts. The preliminary phase examined early settlement newspapers to trace changes in agricultural and cultural events in the rural communities of the study area. Journals of military expeditions and diaries by early residents gave insights into the vegetation of the mid to late 1900’s. Interviews with a Figure 1—Location of Flint Hills Region Four County Study Area. In: McArthur, E. Durant; Ostler, W. Kent; Wambolt, Carl L., comps. 1999. Proceedings: shrubland ecotones; 1998 August 12–14; Ephraim, UT. Proc. RMRS-P-11. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Thomas A. Eddy is Professor, Division of Biological Sciences, Emporia State University, Emporia, KS 66801. 56 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-11. 1999 ranching family whose great grandfather had homesteaded in the area was valuable in understanding early land use philosophy and practice. Secondly, the history of the occurrence of woody vegetation in the area was assembled by examining section line surveys by the Federal Land Office in 1856 and 1857, aerial photographs taken in 1937-1939 and later in 1950, 1956, 1969, and current aerial photographs and soil maps. Fifty sites (200 m sq) were selected in each of the four counties as sites to compare the vegetation changes over the past 15 decades. Woody vegetation composition and foliar cover (Daubenmire method) was determined for each 200 m sq site. The burning history of 157 sites was collected from ecological records and interviews of land owners and managers. A comparison was made of the woody vegetation on slopes (hill top to bottom slope) on burned and unburned sites on the study area in Chase county. The third aspect of the study evaluated the economic impact of the loss of the forage to invading woody plants and the subsequent loss of income to the ranching industry. Analysis of vegetation in the transects of the study sites and 1⁄2 cm overlay grids on early and recent aerial photographs were used to calculate the extent of the woody invasion into the four-county study area and to estimate the percent closure of the canopy of woody plants over the grass and forbs. Each acre lost to grazing was assigned the current rental value of $18.00/acre/year. The fourth objective was to develop management strategies to reduce losses in livestock forage from weedy plant invasions and maintain the productive herbaceous species. This was accomplished by examination of the scientific literature, interviews with range management specialists, and observations based on my field experiences in the study areas. Results ________________________ Woody plants have invaded all unburned prairie sites in the study area. Burned pasture sites (where burning has occurred in at least once every 4 years) showed a slow increase in woody plants from 0 to 5% through the period (150 years) (table 1). Distribution of woody plants on slopes that burned regularly was linear from hill top (1%) to bottom slope (20%) (table 2). On unburned areas woody plant infestations occurred on 3% of the hill top sites to 100% of the slower slope sites. Table 1—Tree and shrub invasion of burned and unburned prairie sites in the central Flint Hills study areas in Kansas, 1860-1998. Year 1860 1900 1940 1960 1980 1998 Average percent sites/woody plants Burned Unburned 0 0 1 2 3 5 1 2 24 40 64 100 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-11. 1999 Table 2—Effects of slope on occurrence of woody plants on burned and unburned sites in the central Flint Hills study areas in Kansas, 1998. Slope Average percent sites/woody plants Burned Unburned Hill top Upper slope Mid slope Lower slope Bottom slope 1 4 7 12 20 0 2 3 82 100 Five primary woody species were identified on the study areas of both burned and unburned sites. Frequency of occurrence on burned sites was one-third that of unburned sites, and percent foliar density of burned sites was one-fifth that of unburned sites (table 3). The invasion of woody plants into prairie may be attributed to events in the history of the region since the Homestead Act of 1857 (table 4). Economic losses to the ranching industry in the fourcounty study area from forage destroyed by invading shrubs was estimated to be $317,000 annually (table 5). Control of woody species must be based on careful balance of range forage with numbers of livestock on the pastures (carrying capacity), selective use of woody plant herbicides, burning practices that maximize woody plant damage by allowing for adequate accumulation of fuel, and mowing of vulnerable plants. Discussion _____________________ Penetration of woody plants into the remaining tallgrass prairie in the study area in east central Kansas has resulted from reduction of the intensity and frequency of prairie fires. The role of fire in maintaining the integrity of the tallgrass ecosystem has been described by plant ecologists (Weaver and Rowland 1952; Bragg and Hulbert 1976; Steinauer and Collins 1996). Several aspects of the ecology of fire and its effect on the grassland flora were addressed by this study. Trees and shrubs successfully invaded all unburned prairie sites examined in the four-county study area. This infestation of woody plants has degraded the value of the prairie for forage for livestock and has altered the composition of the native tallgrass communities. On sites burned regularly there has been a gradual increase in woody plant invasion over the past 15 decades. Invasion has occurred in various locations in the prairie where overgrazing by livestock has reduced the fuel (previous years’ dead plant remains) to levels inadequate to carry fire hot enough to destroy woody plants establishing on the site. Eventually the tree and shrub-infested site will convert to a shaded woodland environment where further growth of prairie vegetation is suppressed. Entry and establishment of woody plants occurred most frequently in lower and bottom slopes because of the deeper, fertile, moist soils near woodland borders or brushy ravines where sources of woody species occur. 57 Table 3—Composition and foliar density of woody plants on burned and unburned sites in the central Flint Hills study areas in Kansas, 1998. Burned Unburned % occurrence % foliar cover % occurrence % foliar cover Species Cornus drummondii Maclura pomifera Rhus glabra Symphoricarpos orbiculatus Ulmus pumila Other species 10 4 8 6 2 3 3 5 35 15 13 10 18 24 12 11 2 8 1 1 7 4 10 9 Table 4—Historical influences on increase of woody plants on unburned prairie sites in the central Flint Hills study areas in Kansas, 1998. Historical event Beginning of period Homestead Act Small farms on prairie WWI Depression Large farms Modern farming 1857 1875 1918 1930 1960 1980 % Sites with woody plants 1 18 28 55 78 100 Table 5—Estimated annual costs of tree and shrub invaded prairie to ranching interests in the central Flint Hills study areas, Kansas. 1998. County Grazed acres (non federal) Chase Greenwood Lyon Morris Total 404,900 612,900 262,900 262,500 1,543,200 a 4,700 6,100 3,300 3,400 17,500 Annual cost of invaded acresa $85,000 $110,000 $60,000 $62,000 $317,000 $18.00/acre/yr The history of the decline of acreage and quality of the tallgrass prairie in the four-county area was attributed to six periods of human activity during the past 150 years. Each of these brought unique demands on the prairie landscape. The Homestead Act (1857) opened the prairie for settlement with the accompanying need to suppress and break native sod for crops. Small farms (1860-1900) with associated roads, small fields, orchards, and home sites brought an end to prairie burning in many areas. Farm failures during the 1930’s resulted in abandonment of many prairies, where in the absence of management, pastures and old crop fields were invaded by woody species. World War II (1940’s) accelerated the loss of prairie acres to more intensive agriculture as the nation’s demand for food increased. Large farms and modern machines (1960’s to present) caused the remaining loss of acres suited to cropland agriculture. As small farms were replaced by large farming operations, small pastures and isolated old crop fields were left to woody plant invasion. 58 Acres lost of woody plant invasion Economic losses due to reduction in forage caused by woody plant invasion indicates the effect on the families in the region who depend on ranching for their income. Many acres of prairie can be returned to productivity if aggressive control of woody species is practiced. References _____________________ Bragg, T. B.; Hulbert, L. C. 1976. Woody plant invasion of unburned Kansas bluestem prairie. Journal of Range Management. 29: 19-23. Steinauer, E. M.; Collins, S. L. 1996. Prairie ecology: the tallgrass prairie. In: Prairie Conservation. Sampson, F. B., Knopf, F. L., editors. Island Press. Washington DC. Weaver, J. E.; Rowland, N. W. 1952. Effects of excess natural mulch on development, yield, and structure of native grassland. Botanical Gazette. 114: 1-19. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-11. 1999