Public Values for Riparian Ecosystems: Experimental ... in the West and Implications ...

advertisement

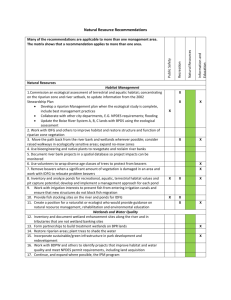

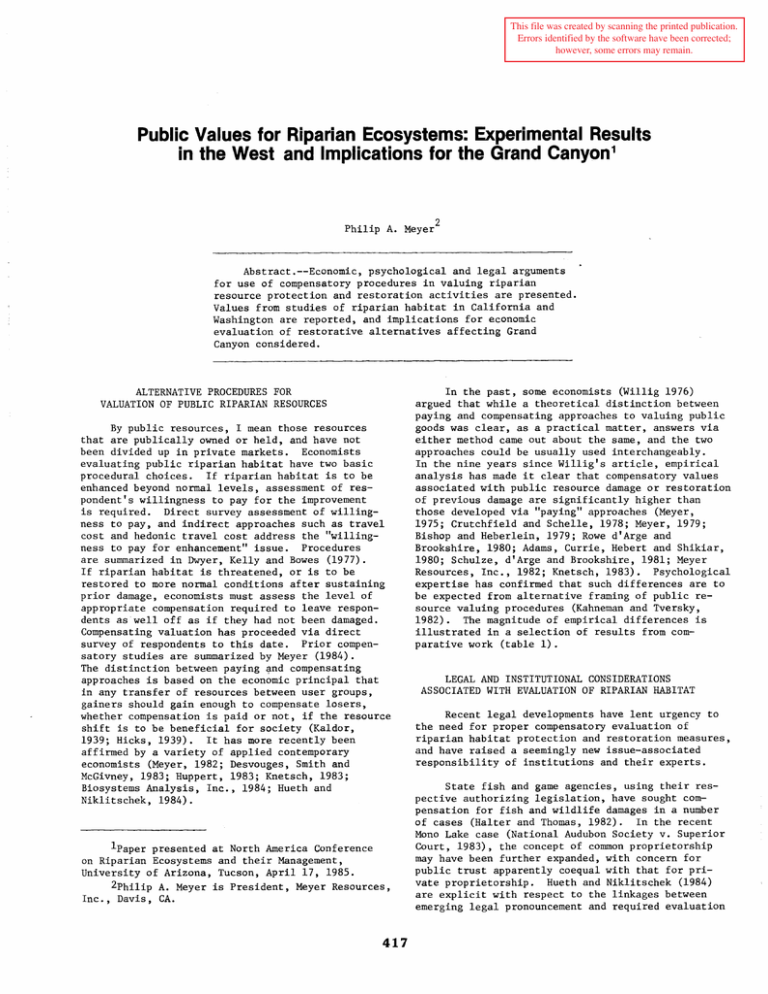

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Public Values for Riparian Ecosystems: Experimental Results in the West and Implications for the Grand Canyon 1 Philip A. Meyer 2 Abstract.--Economic, psychological and legal arguments for use of compensatory procedures in valuing riparian resource protection and restoration activities are presented. Values from studies of riparian habitat in California and Washington are reported, and implications for economic evaluation of restorative alternatives affecting Grand Canyon considered. ALTERNATIVE PROCEDURES FOR VALUATION OF PUBLIC RIPARIAN RESOURCES By public resources, I mean those resources that are publically owned or held, and have not been divided up in private markets. Economists evaluating public riparian habitat have two basic procedural choices. If riparian habitat is to be enhanced beyond normal levels, assessment of respondent's willingness to pay for the improvement is required. Direct survey assessment of willingness to pay, and indirect approaches such as travel cost and hedonic travel cost address the "willingness to pay for enhancement" issue. Procedures are summarized in Dwyer, Kelly and Bowes (1977). If riparian habitat is threatened, or is to be restored to more normal conditions after sustaining prior damage, economists must assess the level of appropriate compensation required to leave respondents as well off as if they had not been damaged. Compensating valuation has proceeded via direct survey of respondents to this date. Prior compensatory studies are summarized by Meyer (1984). The distinction between paying ~nd compensating approaches is based on the economic principal that in any transfer of resources between user groups, gainers should gain enough to compensate losers, whether compensation is paid or not, if the resource shift is to be beneficial for society (Kaldor, 1939; Hicks, 1939). It has more recently been affirmed by a variety of applied contemporary economists (Meyer, 1982; Desvouges, Smith and McGivney, 1983; Huppert, 1983; Knetsch, 1983; Biosystems Analysis, Inc., 1984; Rueth and Niklitschek, 1984). lpaper presented at North America Conference on Riparian Ecosystems and their Management, University of Arizona, Tucson, April 17, 1985. 2Philip A. Meyer is President, Meyer Resources, Inc., Davis, CA. 417 In the past, some economists (Willig 1976) argued that while a theoretical distinction between paying and compensating approaches to valuing public goods was clear, as a practical matter, answers via either method came out about the same, and the two approaches could be usually used interchangeably. In the nine years since Willig's article, empirical analysis has made it clear that compensatory values associated with public resource damage or restoration of previous damage are significantly higher than those developed via "paying" approaches (Meyer, 1975; Crutchfield and Schelle, 1978; Meyer, 1979; Bishop and Heberlein, 1979; Rowe d'Arge and Brookshire, 1980; Adams, Currie, Hebert and Shikiar, 1980; Schulze, d'Arge and Brookshire, 1981; Meyer Resources, Inc., 1982; Knetsch, 1983). Psychological expertise has confirmed that such differences are to be expected from alternative framing of public resource valuing procedures (Kahneman and Tversky, 1982). The magnitude of empirical differences is illustrated in a selection of results from comparative work (table 1). LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL CONSIDERATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH EVALUATION OF RIPARIAN HABITAT Recent legal developments have lent urgency to the need for proper compensatory evaluation of riparian habitat protection and restoration measures, and have raised a seemingly new issue-associated responsibility of institutions and their experts. State fish and game agencies, using their respective authorizing legislation, have sought compensation for fish and wildlife damages in a number of cases (Halter and Thomas, 1982). In the recent Mono Lake case (National Audubon Society v. Superior Court, 1983), the concept of common proprietorship may have been further expanded, with concern for public trust apparently coequal with that for private proprietorship. Rueth and Niklitschek (1984) are explicit with respect to the linkages between emerging legal pronouncement and required evaluation Table !.--Comparative Responses to Paying and Compensating Approaches for Valuation of Public Resources. Public Resource Ratio of Compensating to Paying Values Author 1. All saltwater fishing within a day's round trip. Meyer (1975) 19:1 2. Favorite fishing site in a region. Sinclair (1976) 20:1 3. Elk hunting in Wyoming Brookshire and Randall (1978) 7:1 4. One acre of Riparian habitat along the Sacramento River. Meyer Resources, Inc. (1982) 5:1 5. Wetland hunting in an area. Hammack and Brown (1974) 4:1 6. Statewide goose hunting for one year. Bishop and Heberlein (1979) 2:1 to 5:1 7. Washington ocean fishing. Crutchfield and Schelle (1978) 4:1 8. Fishing in a park. Ehy (1975) 9. One day of recreation along the Sacramento River. Meyer Resources, Inc. (1982) 4:1 to 5:1 10. Local postal service. Banford (1977) 4:1 11. Fishing pier. Banford (1977) 3:1 procedure for public resources -- and in the context of other recent legal initiative. 3.5:1 no distinction needs to be made between enhancement and mitigation projects. The term enhancement is meaningless, and all projects can properly be regarded as mitigating past losses, until preMcNary Dam run levels have been restored. (p. 93). The purpose of this paper is to examine the different evaluation procedures which might be used for projects intended to mitigate past fishery losses, rather than to enhance production on the Columbi~ system. The need for this work stems from passage of the Pacific Northwest Electric Power Conservation Act of 1980, which directed the Northwest Power Planning Council to "promptly develop and adopt pursuant to this subsection a program to protect, mitigate, and enhance fish and wildlife •.• on the Columbia River and its tributaries" (Section 4Hla). Subsequently, the Northwest Power Planning Council has established the 1953, preMcNary Dam run level as the reference point for mitigation and enhancemen.t projects which are mandated by the Act •••• Such legal perspective and related economic assesments would seem to compel proper compensatory evaluation of restorative alternatives affecting riparian habitat. To proceed otherwise may render agencies and experts vulnerable not only to criticism on the basis of economic theory, but to legal challenge and possible liability (Honour Brown v. U.S • A. , 19 84) • EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE CONCERNING COMPENSATORY VALUES FOR RIPARIAN HABITAT This section reports on two studies providing initial data on the value of riparian habitat. The first study, conducted for the California Resources Agency, surveyed residents of Sacramento and Colusa, California to develop "fair compensatory values" for riparian habitat along the Sacramento River (Meyer Resources, Inc. 1982). The second study, conducted with Biosystems Analysis, Inc. for the Bonneville Power Administration developed ecologically based economic values for old growth Douglas fir forest in Western Washington state (Biosystems Analysis, Inc.; 1983). These data are preliminary, andrevised estimates based upon further th~oretical In general, economic evaluation procedures change as the institutional environment changes. The viewpoint of this paper is that passage of the Act and establishment of pre-McNary run size as goals for fishery runs has given the potential beneficiaries of increases in runs a right to fish production up to the levels established by the Council. Until such levels have been attained, whether by on-site or off-site projects, 418 modification recently completed by the author are expected to render them somewhat conservative. They are based on direct evaluation of habitat as it supports a variety of nature-based activities and interests. Details for each analysis can be obtained from the indicated source documents. Annual value per acre, and total present value per acre are displayed in table 2. THE RELEVANCE OF REQUIRED ECONOMIC VALUING PROCEDURES FOR RIPARIAN RESOURCES IN THE G~D CANYON In conclusion, it seems appropriate at this Arizona conference, to reflect on the implications developed here for economic value work associated with riparian habitat in Grand Canyon National Park. Such comments appear timely. In 1963, completion of a hydro-electric peaking facility at Glen Canyon resulted in flows sometimes going from 3,000 to 25,000 cfs. in a 24 hour period. This has degraded recreation use conditions both on the Colorado River and along its banks, with attendant impact, one would suspect, on riparian communities. In response to these concerns, the U.S .• Bureau of Reclamation, in association with the National Park Service advertised in 1984 to conduct a Grand Canyon Recreation Study (USBR, 1984). One of the purposes of this study was to estimate the economic value of public activities based upon the riverine and riparian features of the Canyon, presumably for use in evaluating alternative flow regimes to restore ecological and recreational viability along the river. Instructions identified that only a "willingness to pay" approach to evaluation could be used, however, thus preempting the greater part of any economic value that might be developed. Originating authors may have believed that they were proceeding with whatever technology was available. It is clear from the information provided here, however, and from empirical results concerning the economic value of riparian and related resources developed elsewhere, that willingness to pay evaluation of restorative improvements in Grand Canyon National Park are not consistent with economic theory and may also not be consistent with legal obligation. More importantly, they are likely to develop values that significantly underestimate the public's interest in restoration of riparian capabilities in the Grand Canyon, relative to alternative more appropriate valuing procedures that are available. Thus, while applauding the initiative of agencies who are moving forward to address the issue of restoring riparian habitat and other riverbased opportunity in the Grand Canyon, I call upon them to review their program, and make such midcourse corrections as may be necessary to expand its scope to include a full and comprehensive evaluation of the restorative opportunities at hand. Table 2.--Per Acre Preliminary Value Estimates for Riparian Habitat. Total Present Annual Valuel Value -----$ per Acre-------A. Sacramento River Riparian Habitat 1. Thirty-foot leave strip along the river bank. 1,663 52,549 2. Full riparian between s:et back levies. 3,625 114,546 B. Old Growth Douglas. Fir Forest in Western Was.hington 3. Based on estimate of 1,362 330,0QQ acres of old growth still remaining in Western Washington. 43,0.38 4. Based on a hypothetical reduction in remaining total acreage to 230,00.0 acres. 2,229 22,553 5. Based on a hypothe- 10,680 tical reduction in remaining total acreage to 64,000 acres. 337,476 lTotal present value is calculated at 3 per cent rate of discount. Some agencies confuse interest rates with discount rates, and use a higher discount rate. We concur with the increasing use of 3 percent by federal and state agencies in the energy field, and use it here. A theoretical discussion of discounting issues is found in Lind et. al. (1982). LITERATURE CITED Adams, R.C., J.W. Currie, J.A. Hebert and R. Shikiar. 1980. The visual aesthetic impact of alternative closed cycle cooling systems. BatellePacific Northwest Laboratory. The economic value of riparian habitat will vary with habitat type and quality, with the total amount of riparian habitat generally available and with other local circumstance. These values do possess a relative degree of comparability, however, and will serve as initial estimates until further work can be completed. Banford, Nancy. 1977. Willingness to pay and compensation needed: valuation of pier and postal service. Unpublished paper, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver. Biosystems Analysis, Inc. 1984. Methods for valuation of environmental costs and benefits of hydroelectric facilities. Report to Bonneville Power Administration, DOE/BP-266. 419 Bishop, Richard C. and Thomas A. Heberlein. 1979. Measuring values of extra-market goods: are indirect measures biased? American Journal of Agricultural Economics 61-5, December. Knetsch, Jack L. 1983. Property rights and compensation. Butterworths, Seattle. Lind, Robert C., Kenneth J. Arrow, Gordon R. Corey, Partha Dasgupta, Amartya K. Sen, Thomas Stauffer, Joseph E. Stiglitz, J.A. Stockfisch and Robert Wilson. 1982. Discountii'lsz for time and risk in energy_policy. Resources the Future, Washington, D.C. Brookshire, DavidS. and Alan J. Randall. 1978. Public Policy alternatives, public goods and contingent valuation mechanisms. Resource and Environmental Economics Laboratory, University of Wyoming, Laramie. Crutchfield, James A. and Kurt Schelle. 1978. On economic analysis of Washington ocean recreational salmon fishing with particular emphasis on the role played by the charter vessel industry. Department of Economics, University of Washington, Seattle. Desvouges, William K., V. Kerry Smith and Matthew P. McGivney. 1983. A comparison of alternative approaches for estimating recreation and related benefits of water quality improvements. Research Triangle Institute, EPA 230-05-83-001, Triangle Park, N.C. Meyer, Philip A. 1975. A comparison of direct questioning methods of obtaining dollar values for public recreation and preservation. Environment Canada, Vancouver. 1979. Pub~ically vested~values for fish and wildlifei criteria in·Jecon:omic welfare and interface with the law. Land Economics 55 (May). 1982. Net economic values for salmon and steelhead from the Columbia river system. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS F/NWR-3. Dwyer, John F., John R. Kelly and Michael D. Bowes. 1977. Improved procedures for valuation of the contribution of recreation to national economic development. University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. 1984. A survey of existing information to include social or non-market values that are useful for salmon and steelhead management decisions. In, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS F/NWR-8. Eby, Philip A. 1975. The value of outdoor recreation; a case study. Master Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Meyer Resources, Inc. 1982. Economic valuation of river projects-values for fish, wildlife and riparian resources. Report to the California Resources Agency, Sacramento. Halter, Faith and Joel T. Thomas. 1982. Recovery of damages by States for fish and wildlife losses caused by pollution. Ecology Law Quarterly, 10-5. National Audubon Society v. Superior Court. 33 Cal. 3d, 419. Hammack, Judd and Gardner M. Brown. 1974. Waterfowl and wetlands: toward bioeconomic analysis. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. Hicks, John R. 1939. The foundations of welfare economics. Economic Journal, 49-699. Honour Brown v. U.S.A. 1984. of Mass. 81-168-T. 1983. Rowe, R.D., Ralph C. d'Arge and DavidS. Brookshire. 1980. On experiment on the economic value of visibility. J. Environmental Economics and Management, 7-1. Schulze, William D., Ralph d'Arge and DavidS. Brookshire. 1981. Valuing environmental commodities: some recent experiments. Land Economics, 58-151. U.S. District Court Sinclair, William F. 1978. The economic and social impact of the Kemaro II hydroelectric project on British Columbia's fisheries resources. Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Vancouver. Rueth, Darrell L. and Mario Niklitschek. 1984. Mitigation and enhancement project evaluation procedures for salmon and steelhead fish runs on the Columbia river system. In, Making economic information more usefu~for salmon and steelhead production decisions. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS F/NWR-8. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 1984. Solicitation for Grand Canyon recreation study. Sol. No. 4-SP-40-01780. Huppert, Daniel D. 1983. NMFS guidelines on economic evaluation of marine recreational fishing. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFSSWFC-32. Willig, Robert D. out apology. (Sept.). Kahneman, Daniel and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 49-263. Kaldor, Nicholas. 1939. Welfare propositions of economics and interpersonal comparisons of utility. Economic Journal, 49-549. 420 1976. Consumer's surplus withAmerican Economic Review, 66