The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Bulletin of Wake Forest University

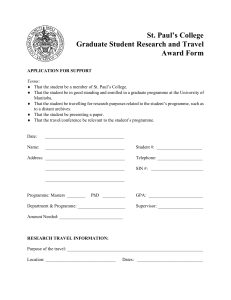

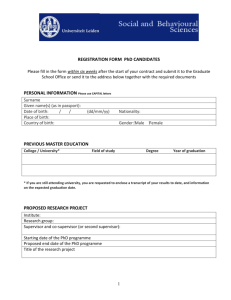

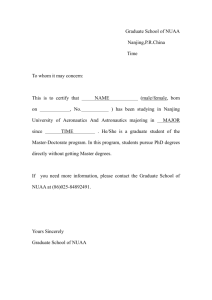

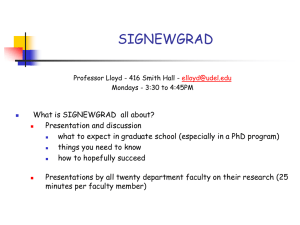

advertisement