E GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES CHAPTER III

advertisement

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

E

xternal current account deficits or

surpluses in some major economic

areas—notably the United States and

Asia—have reached record-high levels,

and expectations are that they will stay large or

increase for some time. Many observers, including IMF staff, have expressed concern that corrections to sustainable levels will likely require

large exchange rate adjustments, especially

against the U.S. dollar, with possibly disruptive

effects on global financial markets and economic activity.1 In contrast, other observers are

less concerned, arguing that a benign resolution

of global imbalances is likely with today’s deep

economic and financial integration.2

Some recent developments suggest that

globalization—the increasingly global dimension

of economic and financial transactions—has

changed the environment for external imbalances and their adjustment. For instance, it may

be argued that larger external current account

deficits or surpluses are the natural outcome of

the increased scope for cross-border trade in

financial assets, and that higher trade openness

and greater competition worldwide are likely to

have facilitated adjustment of global imbalances.

However, globalization has also brought new

challenges and risks. Larger external positions

raise economies’ exposure to financial market

disturbances, increasing the risks associated with

an abrupt realignment in investors’ expectations. Finally, the relationship between globalization and external adjustment can be more

ambiguous than suggested by casual observation.

Some aspects of globalization—including, for

example, more specialization in production—

may, at least in theory, hinder rather than facilitate adjustment.

Against this background, this chapter will

examine implications of globalization for external imbalances and their adjustment. The relationship between globalization and external

imbalances is complex and encompasses many

aspects. For tractability, the chapter will focus on

aspects that are particularly relevant from the

perspective of the unwinding of current imbalances, and the related risks. To this end, it is

organized in three parts.

• The first part discusses the rapid expansion of

two-way capital flows and the corresponding

increases in gross external asset and liability

positions and then examines the implications.

The chapter finds that these developments

have contributed to an environment in which

large current account surpluses or deficits can

emerge and be sustained and argues that this

can be helpful insofar as it allows for gradual

rebalancing. Moreover, while economies’

exposure to market and exchange rate

changes has increased with larger gross external positions, these valuation effects can, perhaps paradoxically, to some extent facilitate

external adjustment among industrial countries, as they are, in effect, wealth transfers

from countries with appreciating currencies to

countries with depreciating currencies. The

chapter notes, however, that these benefits

could turn into a liability if policies are not

consistent with a credible medium-term policy

framework aimed at external and internal balances, as expectations may not be well

anchored. In this case, investor preferences

Note: The main authors of this chapter are Thomas Helbling, Nicoletta Batini, and Roberto Cardarelli, with support

from Douglas Laxton, Dirk Muir, Panagiotis Konstantinou, Philip Lane, and Linda Tesar. Nathalie Carcenac provided

research assistance.

1See “How Worrisome Are External Imbalances?” Chapter II, World Economic Outlook, September 2002, and Obstfeld and

Rogoff (2001, 2004).

2See Cooper (2001, 2004).

109

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

may quickly change and the fallout from disruptive financial market turbulence would

likely be more elevated than it had been.

• In the second part, the chapter turns to real

globalization and examines how a broad fall in

trading costs has affected the magnitudes,

composition, and direction of trade flows as

well as other key determinants of external

adjustment. It finds that trade shares have

increased and the global distribution of trade

flows has become more equal, as emerging

markets have become more integrated, but it

notes that the empirical evidence on how real

globalization has affected price and demand

elasticities of trade flows is inconclusive.

• In the third part of the chapter, simulations

of the IMF’s new multicountry Global

Economic Model (GEM) are used to analyze

the combined effects of real and financial

globalization on the adjustment of external

imbalances. The chapter finds that real and

financial globalization should generally facilitate global rebalancing, provided financial

conditions remain benign, reflecting, among

other factors, the better burden sharing

implied by the more even distribution of

trade flows across the globe. It also shows,

however, that globalization has not fundamentally changed the nature of adjustment, nor

the magnitudes involved, and that larger net

foreign asset positions raise the potential risks

associated with unexpected changes in

investor preferences.

Overall, the chapter concludes that policymakers need to be very mindful of the risks associated with global imbalances, while at the same

time taking advantage of the scope that globalization provides to facilitate adjustment.

At the outset, two points should be noted.

• The chapter adopts a broad notion of globalization, its causes, and its impact. In particular,

while using as a starting point the narrow defi-

nition of an acceleration in the pace of growth

of international trade in goods, services, and

financial assets relative to the rate of growth in

domestic trade, the chapter also considers

phenomena such as the integration of emerging market economies, greater competition,

or reduced exchange rate pass-through,

which—while related to globalization—also

reflect other factors, including more credible

monetary policy frameworks.

• The chapter is not intended to cover the specific policies needed for the orderly resolution

of current imbalances, which are discussed in

Chapter I, or how the current imbalances have

emerged (see Chapter II, World Economic

Outlook, September 2002, and Hunt and

Rebucci, 2003, for recent discussions).

Moreover, it focuses mostly on industrial and

key emerging market countries that are highly

integrated and likely to play a major role in

the rebalancing.

Financial Globalization

Financial globalization—the global integration of capital markets—has accelerated noticeably since the early 1990s, as illustrated, for

example, by the rapid simultaneous increase in

many countries’ foreign assets and liabilities

(Figure 3.1).3 The trend toward larger external

assets and liabilities has been particularly relevant for industrial countries, where, relative to

output, both average external assets and liabilities about tripled between 1990 and 2003, reaching levels of more than 200 percent by the end

of the period.4 While the broad trend for emerging market countries has been similar, average

increases for these countries have been smaller

since the mid-1990s and, on a global scale, their

gross external positions remain relatively small

compared with those of industrial countries

(Table 3.1).

3See Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2003, 2005a). There are other measures of financial globalization, including price-based

measures or the correlation between saving and investment. See Obstfeld and Taylor (2004) for empirical evidence based

on other measures that suggest similar broad trends.

4The data on gross foreign assets and liabilities used in this chapter are taken from the latest version of the database

developed by Philip Lane and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti (and used in Lane and Milesi-Ferretti, 2005b).

110

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

The recent bout of financial globalization is

partly associated with the decline in information

processing and dissemination costs that have

fostered cross-border trade in an expanding

variety of financial instruments through decreasing transaction costs (Figure 3.2). Domestic

and external financial liberalization have played

a major role since the early 1970s when the

current era of financial globalization began

after a long period of financial disintegration

(see Box 3.1 for a comparison of the current

era of globalization with earlier ones).5 Finally,

real and financial globalization tend to stimulate each other. Increased trade flows, for

example, tend to lead to larger gross capital

flows, reflecting trade finance, among other

factors.

This section will examine two issues related to

the surge in international financial transactions.

First, it will analyze whether investors’ increased

incentives for international portfolio diversification have reduced the extent to which financial

markets still restrict net international borrowing

(the financing need associated with current

account deficits) and net foreign liabilities (the

corresponding stock measure). Second, it will

investigate the extent to which larger holdings of

foreign assets and liabilities expose investors to

greater valuation risks and what this means for

external adjustment.

While data on external assets and liabilities

have greatly improved so that more systematic

empirical analysis is possible compared with

some 10 years ago, important caveats nevertheless remain (see Box 3.2 on data issues).

Globalization and Net Foreign Assets

Traditionally, investors place the bulk of their

financial wealth in domestic assets despite more

favorable risk-return profiles—before transaction

costs and taxes—of globally diversified portfolios

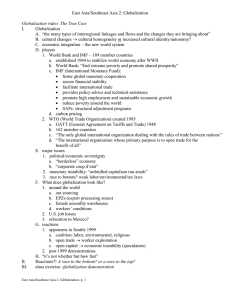

Figure 3.1. Financial Globalization Trends, 1970–2003

(Percent of GDP)

Global financial market integration has proceeded rapidly, especially in industrial

countries, since the early 1990s.

Average

250 Industrial Countries: Foreign

Assets

Standard deviation

Emerging Market Countries:

Foreign Assets

100

200

80

150

60

100

40

50

20

0

1970

80

90

2000

250 Industrial Countries: Foreign

Liabilities

1970

80

90

2000

Emerging Market Countries:

Foreign Liabilities

0

100

200

80

150

60

100

40

50

20

0

1970

80

90

2000

1970

80

90

2000

0

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics; IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics; Lane

and MiIesi-Ferretti (2005b); and IMF staff calculations.

5See, among others, Edey and Hviding (1995) or

Williamson and Mahar (1998). The end of the Bretton

Woods regime of fixed but adjustable exchange rates also

contributed, as trade in foreign exchange and related

instruments began to spiral with floating rates.

111

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

Table 3.1. Gross Assets and Liabilities, 1980–2003

(Billions of U.S. dollars, excluding foreign assets held by central banks)

External Assets

Industrial countries

North America

United States

Europe

France

Germany

United Kingdom

Asia and Pacific

Japan

Emerging markets and other

developing countries

Emerging Asia

China

Korea

Malaysia

Thailand

Latin America

Argentina

Brazil

Mexico

Others

External Liabilities

Industrial countries

North America

United States

Europe

France

Germany

United Kingdom

Asia and Pacific

Japan

Emerging markets and other

developing countries

Emerging Asia

China

Korea

Malaysia

Thailand

Latin America

Argentina

Brazil

Mexico

Others

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2003

2,287

668

584

1,474

203

216

519

145

134

3,975

1,310

1,185

2,232

265

308

838

433

410

9,701

2,331

2,119

5,522

722

1,017

1,695

1,848

1,778

15,334

4,107

3,754

8,659

1,292

1,579

2,342

2,568

2,445

26,810

7,914

7,265

16,066

2,323

2,504

4,400

2,830

2,605

36,039

8,454

7,680

24,311

3,317

3,867

6,293

3,273

2,922

114

28

...

4

4

1

55

4

10

9

31

193

72

18

7

7

2

80

5

19

21

42

366

166

25

17

5

7

126

6

29

37

74

711

384

47

58

13

14

214

3

51

50

113

1,479

948

225

103

39

22

325

3

74

45

206

1,849

1,193

273

127

53

23

386

2

96

30

270

2,485

708

525

1,578

193

224

508

198

147

4,186

1,464

1,206

2,311

306

289

755

411

307

10,531

2,909

2,459

5,835

845

751

1,762

1,787

1,529

16,139

4,849

4,274

9,096

1,385

1,535

2,426

2,194

1,812

28,419

9,741

8,965

16,386

2,214

2,534

4,497

2,293

1,808

39,039

11,452

10,476

24,790

3,247

3,794

6,429

2,797

1,979

552

138

...

33

12

10

267

29

90

66

147

905

284

27

59

31

20

395

54

121

108

226

1,298

493

77

55

31

41

492

70

153

134

313

2,378

1,125

255

147

81

138

819

144

241

230

435

3,527

1,626

479

195

101

116

1,247

236

403

309

654

4,208

2,116

659

293

115

111

1,310

192

420

362

782

Sources: Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2005b); IMF, International Financial Statistics, and IMF staff calculations.

(the so-called home bias in asset holdings).6

Clearly, with globalization, opportunities for

international diversification have improved, as

important obstacles, such as high cross-border

transaction and information costs or regulatory

barriers, have been reduced.7 One would therefore expect that the home bias has decreased at

the global level.

6Since asset returns are only partially correlated across countries, investors may reduce risks that are specific to their

home country with international diversification (e.g., Solnik, 1974, or Obstfeld and Rogoff, 1996).

7Explanations of the home bias focus on factors reducing the incentives for international diversification, including high

transaction costs in cross-border transactions compared with domestic transactions, problems of cross-border information

dissemination, differences in regulatory regimes and regulatory barriers (e.g., regulations restricting foreign investment by

pension funds), and differences in consumption baskets, owing to the presence of transport costs (nontraded goods), but

112

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

The decline in home bias matters for external

imbalances and their adjustment because it

determines the extent to which desired current

account balances8—which depend on factors

such as productivity growth differentials or

demographic changes—are accommodated by

international financial markets.9 If home bias

is strong, global demand for foreign assets will

be low and price-inelastic. Large issuers of

foreign liabilities will thus face high yields;

this will discourage net external borrowing,

and actual current account balances will likely

be smaller than desired ones. On the other

hand, if home bias is small, demand for foreign

assets will be higher and more price-elastic,

and larger net external liabilities will be less

costly. That said, net external borrowing will

remain limited by solvency considerations:

countries need to be able to amortize external

liabilities.

Over the past two decades, there is clear evidence that the home bias has declined and that

restrictions on net external borrowing have

eased.10

• Portfolio holdings of foreign bonds and

equity in some major industrial countries,

such as Canada, Germany, Japan, and the

United Kingdom, have clearly increased compared with domestic market capitalization

(Table 3.2).

• External current account deficits or surpluses

(relative to domestic incomes) have, on

also differences in taste. See, among others, French and

Poterba (1991), Tesar (1993), Tesar and Werner (1995),

Baxter and Jermann (1997), Baxter, Jermann, and King

(1998), or Obstfeld and Rogoff (2001).

8Defined as current account balances that would prevail

with no restrictions on international capital market access

and an infinitely elastic supply of capital.

9Financial globalization is a necessary condition for

larger current account deficits or surpluses but not necessarily a main cause. For example, international risk diversification alone may not generate net external borrowing

or lending: domestic investors can acquire foreign equity

with the proceeds from selling domestic equity to foreign

residents. Gross capital flows will increase, but inflows are

exactly matched by outflows.

10Evidence on the degree of remaining restrictions is

broadly similar for other measures. See also footnote 3.

Figure 3.2. Determinants of Financial Globalization

Decreasing communication and information costs and reduced restrictions on

capital flows have fostered financial globalization.

120 Communication Costs

(1990 U.S. dollars)

100

Satellite

charges

80

Internet Users

(percent of total population)

United

States

European

Union

50

40

60

30

Japan

Emerging

Asia

40

20

60

10

Telephone1

0

1930

50

20

World

70

90

1990

95

2000

0

Emerging Market Countries:

Capital Controls2

(percent of all countries)

Industrial Countries: Capital

Controls 2

(percent of all countries)

No restriction

Restriction

100

100

80

80

60

60

40

40

20

20

0

70s

80s

90s

00s

70s

80s

90s

00s

0

Sources: Busse (2003); IMF, Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange

Restrictions (2004); World Bank, World Development Indicators; and IMF staff calculations.

1 Cost of a three-minute phone call from New York to London.

2 Restrictions on international financial transactions.

113

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

Table 3.2. Overseas Portfolio Investment

(Percent of domestic market capitalization)

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2003

Canada

Portfolio investment

Equity

Bonds

2.0

3.1

0.7

1.9

3.2

0.6

2.1

3.6

0.4

2.4

3.5

1.3

6.0

9.6

1.9

12.9

25.4

2.2

18.7

29.3

3.2

14.3

21.2

3.6

Germany

Portfolio investment

Equity

Bonds

4.9

...

...

2.4

...

...

2.7

...

...

5.8

...

...

10.2

...

...

14.5

16.9

13

30.0

37.8

23.0

31.1

42.1

25.7

...

...

1.3

...

2.0

...

6.9

...

10.7

2.2

12.1

4.0

13.6

8.3

16.7

9.9

United Kingdom1

Portfolio investment

Equity

Bonds

9.5

...

...

8.6

...

...

11.4

...

...

27.5

...

...

34.0

33.1

35.6

37.1

33.5

43.4

42.6

40.9

46.4

48.1

52.4

42.1

United States

Portfolio investment

Equity

Bonds

1.5

0.8

2.7

2.1

1.1

3.1

2.3

1.3

3.3

2.2

2.0

2.4

3.5

5.6

2.1

6.4

9.3

3.5

7.8

10.5

3.8

7.4

12.7

2.3

Japan

Portfolio investment

Equity

Bonds

Sources: Tesar and Werner (1995); Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2005b); IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics; national flow of funds and balance

sheet statistics; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: This table extends Table 2 in Tesar and Werner from 1990 to 2003 using similar but not necessarily identical data sources, replacing

1990 values with new data if available.

11991 values rather than 1990.

average, increased while their dispersion

across countries has widened in industrial

countries and, to a lesser extent, in emerging

market countries (Figure 3.3).

• Net external positions have, on average,

widened also, as has their dispersion on

account of the larger and more persistent

current account deficits and surpluses.

A simple way to quantify the decline in home

bias is to compare each country’s actual share of

foreign portfolio assets in its total portfolio asset

holdings with the share of other countries’

assets in the world total of assets (the world

market portfolio). If the former is smaller than

the latter, there is a home bias according to the

so-called international capital asset pricing

model (ICAPM).11 While some of the underlying assumptions are clearly unrealistic, the

model nevertheless provides useful benchmarks. The calculations shown in Table 3.3

suggest that between 1990 and 2003, the home

bias in bond and equity portfolio holdings of

most major industrial countries—except

Japan12—has declined but not disappeared.

This assessment is obviously tentative, given

that the underlying evidence is model-specific

and limited to patterns in major industrial

countries only. Nevertheless, the broad conclusion is similar to that reached in other recent

studies.13

11The ICAPM implies that investors should allocate their risky assets in proportion to the world market portfolio in equilibrium since other allocations involve idiosyncratic risks for which investors will not be compensated. See, among others,

Adler and Dumas (1983), Branson and Henderson (1984), and Harvey (1991).

12In Japan, the home bias has increased despite the increase in the actual share of foreign assets, as the benchmark share

implied by the ICAPM has risen even faster because of the relative decline of Japan’s share in the world market portfolio.

13See, among others, Obstfeld (2004), Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2004a), and Engel and Matsumoto (2004). In contrast,

Heathcote and Perri (2004) argue that the home bias is much smaller than widely thought because their model implies a

lower optimal allocation of financial wealth in foreign assets compared with other models.

114

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

Table 3.3. Portfolio Diversification: Actual

Foreign Shares and Benchmark Foreign Shares

Implied by Other Countries’ Share in World

Market Portfolio

(Percent)

1990

Equity

_________________________

1995

2000

2003

Bonds

___________

2000 2003

Canada

Actual

Benchmark

9.0

97.4

20.6

97.9

25.5

97.4

19.3

97.5

4.0

97.8

4.5

98.1

Germany

Actual

Benchmark

13.2

96.2

13.6

96.8

23.9

96.1

26.3

97.1

20.6

92.7

22.9

92.2

Japan

Actual

Benchmark

2.2

69.0

4.2

79.4

9.1

90.2

10.6

90.9

14.8

82.2

15.1

83.8

United Kingdom

Actual

29.5

Benchmark

91.0

30.1

92.1

38.4

92.0

45.7

92.0

62.0

95.9

69.4

95.4

United States

Actual

Benchmark

9.1

61.4

10.4

53.1

12.5

52.8

4.6

54.4

3.0

59.6

Figure 3.3. External Current Account Balances and Net

External Positions, 1970–2003

(Percent of GDP; absolute values)

5.7

67.5

Sources: Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2005b); IMF, Balance of

Payments Statistics Yearbook and Global Financial Stability Report,

various issues; national balance sheet statistics; Standard and

Poors’ Emerging Markets Factbook, various issues; and IMF staff

calculations.

Note: The home bias can be gauged from the difference between

actual shares of foreign assets in total asset holdings and the

benchmark shares. Actual foreign shares are calculated as foreign

securities held as a share of total securities held by domestic

investors in each category. Benchmark foreign shares are based on

foreign countries’ share in total world market capitalization.

On average, external current accounts and net foreign assets have increased in

industrial and emerging market countries, suggesting that restrictions on net

external borrowing and lending have eased.

Average

5

Emerging Market Countries:

External Current Accounts

10

4

8

3

6

2

4

1

2

0

1970

50

If risk diversification is an important motive

for investors, one would expect that diversification across markets will be broad based.

According to the ICAPM discussed earlier,

investors should allocate their foreign assets

across countries according to their shares in

the world market portfolio. Table 3.4 compares

major industrial countries’ actual foreign

equity allocations across countries with ICAPM

benchmark allocations, taking the overall home

bias as given.14 The results suggest that diversification patterns are indeed broad based.

However, as the example of European countries

Industrial Countries: External

Current Accounts

Standard deviation

80

90

2000

Industrial Countries: Net

External Positions1

1970

80

90

2000

Emerging Market Countries:

Net External Positions1

0

50

40

40

30

30

20

20

10

10

0

1970

80

90

2000

1970

80

90

2000

0

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics; IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics; Lane

and MiIesi-Ferretti (2005b); and IMF staff calculations.

1 Net foreign assets as a percent of GDP.

14The results are based on data from the 1997 and

2002 Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey conducted

under the auspices of the IMF. The general lack of long

time-series data prevents extensive historical analysis.

Geographical patterns in holdings of long-term bonds

are broadly similar.

115

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

Table 3.4. Geography of Cross-Border Portfolio Equity Holdings

(Percent of total foreign portfolio equity holdings; second row contains benchmark shares implied by international capital asset

pricing model)

Source

____________________________________________________________________________________________

United

States

Canada

Japan

United

Kingdom

_____________

_____________

_____________

Euro area

Germany

_____________

Destination

1997

2002

1997

2002

1997

2002

2002

2002

1997

2002

United States

...

...

...

...

49.3

50.2

56.9

48.4

54.9

54.1

51.5

52.0

42.2

55.3

14.7

48.7

25.5

53.5

27.2

51.3

Canada

5.9

4.8

5.0

4.7

...

...

...

...

1.5

2.7

1.4

2.7

0.4

2.9

—

2.5

0.8

2.7

—

2.7

Japan

11.3

18.8

12.2

17.2

6.0

9.8

6.6

9.3

...

...

...

...

6.8

10.6

2.3

9.4

13.6

10.5

10.1

9.9

Euro area

31.2

24.9

26.8

27.5

13.5

13.0

13.3

14.9

16.6

14.1

16.0

16.0

...

...

64.0

11.9

35.4

13.9

32.5

15.8

Germany

5.4

7.0

2.9

5.6

...

3.7

...

3.0

5.5

3.9

2.3

3.2

...

...

...

...

6.4

3.9

4.4

3.2

United Kingdom

18.0

16.9

23.9

15.1

1.2

8.9

11.0

8.2

11.9

9.6

12.6

8.8

23.0

9.3

10.3

8.2

...

...

...

...

Industrial countries

79.2

77.3

78.5

75.6

87.5

88.1

93.2

86.8

91.2

87.2

87.3

85.9

92.7

85.0

97.9

86.6

87.7

87.3

80.9

86.0

Sources: French and Poterba (1991); IMF, Coordinated Portfolio Survey database; Standard and Poors’ Emerging Stock Markets Factbook,

various issues; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: U.S. investors’ holdings of Canadian equity amounted to 5.9 percent of their total foreign holdings in 1997. The benchmark allocation

predicted by the ICAPM for a given total foreign allocation would have been 4.8 percent.

shows, forces of “gravity” are also relevant.

Allocations to closely located countries or

regions tend to exceed benchmark allocations,

reflecting, among other factors, merchandise

trade patterns and the fact that shorter distances and cultural similarities appear to facilitate financial transactions, possibly through

their effects on transaction costs and information asymmetries.15

Despite growing U.S. net external liabilities,

European countries tend to hold less U.S.

equity than implied by the international capital

asset pricing model benchmark. More generally,

unlike in the 1980s, the share of U.S. portfolio

equity liabilities in total foreign portfolio equity

assets of other countries has been somewhat

below ICAPM benchmarks in recent years (see

also Bertaut and Kole, 2004). These observations suggest that more international financial

diversification has led to increased gross capital

inflows to the United States (in U.S. dollar

terms)—given greater overall flows at the global

level—but not to such an extent that investors

are now overweight in U.S. equity (or bonds).16

15The so-called gravity model of international trade suggests that, everything else being equal, neighboring countries

tend to have closer trade linkages than more distant countries (see Chapter II, World Economic Outlook, September 2002, for

a more detailed discussion). Recent research has found that trade-style gravity equations also perform well in explaining

bilateral investment patterns if augmented with financial market-specific variables (see Bertaut and Kole, 2004; Faruqee, Li,

and Yan, 2004; and Lane and Milesi-Ferretti, 2004a).

16This could suggest that the United States has become a relatively less attractive destination for foreign investors for at

least two reasons. First, with the weakening of business cycle linkages among major economic areas during the 1990s

return correlations declined compared with the 1980s. This, in turn, has made broad-based diversification more attractive

(see Heathcote and Perri, 2004). During the 1980s, diversifying internationally with U.S. assets only was perhaps more

attractive, given (1) deep and well-developed U.S. markets and (2) smaller benefits of more broad-based diversification

because of higher cross-country return correlations. Recently, however, return correlations have again increased. Second,

on the supply side, other securities markets have developed rapidly, as manifested in the growth of outstanding issues,

notably in the euro area. This has also increased the scope for broad-based diversification.

116

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

Figure 3.4. Industrial Countries: Long-Term Real

Interest Rates and Net Foreign Assets1

In industrial countries, during the past decades, the relationship between real

interest rates and net foreign assets has weakened, as investors appear more willing

to hold foreign assets.

Average 1982–92

Average 1993–2003

10

8

6

4

Interest rates (percent)

Naturally, these observations are based on the

behavior of portfolio investment flows only, and

general conclusions about the future willingness of investors to hold U.S. assets cannot

be drawn.

Analyzing the long-run relationship between

real interest rates on long-term government

debt—a benchmark for rates of return in a

country—and overall net external positions provides a useful complementary perspective. With

home bias in asset demand, investors should

only be willing to increase the share of foreign

assets in their wealth if they are compensated

with increasing returns. Accordingly, real interest rates in countries with net external liabilities

should, on average, be higher than in countries

with net external assets, suggesting a negative

correlation between real interest rates and net

foreign assets.17 As noted earlier, if the home

bias broadly declines, such portfolio balance

effects should weaken, and the negative correlation between real interest rates and net foreign

positions should decrease in absolute terms. The

evidence shown in Figure 3.4 suggests that this

has indeed happened. The correlation between

the two variables during 1993–2002, while still

negative, was clearly smaller than during

1982–92.

Overall, financial globalization has created an

environment where net external borrowing and

lending are less restricted and where maintaining larger net foreign liabilities appears to

involve relatively lower costs. This can be helpful when it comes to external adjustment and

global rebalancing. For example, everything else

being equal, the United States now appears

more likely to be able to sustain larger net foreign liabilities in the long run at a lower cost

than, say, some 20 years ago. This could allow

for a more gradual adjustment of the same

2

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

0

Net foreign assets to exports ratio

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics; Lane and MiIesi-Ferretti (2005b); and

IMF staff calculations.

1 Real interest rate calculated as nominal long-term interest rate at end of year t

minus the actual inflation rate at end of year t + 1.

17See Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2002b) for a recent

empirical study presenting similar materials. Real

exchange rate changes are another source of return differentials (in the home currency of the investor). See

Branson and Henderson (1984) on the portfolio balance

approach and the role of home bias therein.

117

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

Box 3.1. External Imbalances Then and Now

The current environment of globalized financial markets, which began in the 1970s for the

advanced countries and in the 1980s for the

emerging market countries, had an important

precedent in the four decades before 1914—the

era of the classical gold standard. Both eras of

financial globalization share common features,

including large net capital flows, but there are

also important differences, including today’s

much larger two-way capital flows.1 This box

compares salient features of financial globalization during 1870–1914 with those of today,

examines whether the large net capital flows in

the earlier era represented a global imbalance

comparable to that of today, and seeks to establish lessons from the earlier era.

Important common features in both eras of

globalization include the following.

• Large net capital flows and current account deficits

and surpluses. The 50 years before World War I

saw massive net private flows of capital from the

core countries of Western Europe to recent settlements overseas (mainly the rapidly developing Americas and Australasia). At the peak, the

associated current account surpluses in Britain

reached 9 percent of GDP and were almost as

big in France, Germany, and the Netherlands

(see the figure). For the principal capital

importers in the late nineteenth century

(Argentina, Australia, and Canada),2 current

account deficits exceeded 5 percent of GDP on

average. By comparison, over the past two

decades, current account surpluses and deficits

have been, on average, increasing, as discussed

in the main text, but they are still smaller than

during the gold standard era, in industrial and

emerging market countries alike. Another striking feature of the pre-1914 data is the high persistence in current account imbalances, even

when compared with today’s relatively persistNote: The main author of this box is Michael Bordo.

1See Bordo, Eichengreen, and Kim (1998), and

Obstfeld and Taylor (2004).

2Earlier in the century, the United States experienced similar net inflows but by the end of the nineteenth century, the country began running current

account surpluses.

118

Current Account Balances

(Percent of GDP)

Surplus Countries

(during gold standard)

10

Germany

5

0

France

-5

United

Kingdom

-10

1870 80 90 1900 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 2000

Deficit Countries

(during gold standard)

-15

15

Canada

10

5

0

-5

-10

-15

Australia

-20

-25

Argentina

1870 80 90 1900 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 2000

-30

-35

Sources: Obstfeld and Taylor (2004); and IMF staff calculations.

ent ones (Bordo, Eichengreen, and Kim, 1998;

and Obstfeld and Taylor, 2004).

• Current account reversals. Although current

account imbalances were generally more longlived in the pre-1914 era than in the recent

period, they were punctuated in some countries

by severe reversals, especially in the crisis-ridden

1890s (Bordo and Eichengreen, 1999). Current

account reversals have reemerged in today’s era

of financial globalization. In fact, Bordo and

others (2001) argue that the total incidence of

financial crises has been greater during the

post–Bretton Woods period than during the earlier period, although the output losses from

crises were somewhat larger pre-1914.

There are also important differences between

the two eras.

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

• Distribution of current account deficits and surpluses.

Under the gold standard, countries of new settlement—the emerging markets of the time—ran

current account deficits while the major European economies had surpluses. In the current

era, core industrial countries run either persistent deficits or surpluses, with domestic savinginvestment imbalances redistributed primarily

among industrial countries rather than from

the core to the periphery as in the earlier era.

• Gross external positions are generally larger today.

Gross external positions were very close to net

positions before 1914—that is, net creditors

had large foreign asset positions whereas net

debtors had large liabilities. In contrast, most

major industrial countries today are both major

creditors and debtors irrespective of their net

position. The earlier pattern reflects the prevalence of long-term investment by the core countries in the countries of new settlement, seeking

higher returns by financing railroads and other

infrastructure as well as budget deficits (especially in the form of bonds but also in the form

of foreign direct investment). The substantial

growth of two-way flows between advanced

countries since 1980 has been associated with

both international financial diversification and

intertemporal consumption smoothing, as discussed in the main text.

• The adjustment mechanism is different. The historical record shows that adjustment to the significant and persistent external imbalances in the

pre-1914 era occurred largely through the

Humean price-specie-flow mechanism of the

classical gold standard (Bordo, 1984). Gold

flows ensured that equilibrium was restored

through changes in money supplies, the terms

of trade, and real exchange rates. In contrast,

the global economy is now on a managed

floating exchange rate regime, and external

adjustment depends no longer on gold flows

but on changes in exchange rates and international reserves, along with relative price movements, short-term capital flows, and valuation

effects (see Obstfeld, 2004).

Despite the fact that external imbalances were

often larger and more persistent before 1914

than they are today, contemporaries in the earlier

era did not view this as a problem for two broad

reasons. First, they strongly believed that except

in extreme situations (e.g., wars) the adjustment

mechanism described above would always be

stabilizing. Second, the nature of foreign investment was quite different. Most of the long-term

flows were to countries with abundant natural

resources and land on the one hand, and scarce

labor and capital on the other. Returns on labor

and capital were thus higher than in the more

developed countries, with excellent prospects of

sustained rapid long-term growth. The activities

financed tended to be those in which information asymmetries could be most easily overcome:

railroads and government (Bordo, Eichengreen,

and Irwin, 1999). Many recipient countries

tended to have sound institutions and sound fiscal fundamentals, further reducing the likelihood

of default, and many adhered to the gold standard, which served as a signal of fiscal rectitude

(“a Good Housekeeping seal of approval” (Bordo

and Rockoff, 1996)). In addition, many recipient

countries were part of the British Empire, with a

de facto British government guarantee that virtually eliminated country risk. That said, not all of

the recipients of foreign capital had such sound

fundamentals. Many of the countries of peripheral Europe and Latin America were prone to fiscal and monetary instability. Their record of

defaults and currency crises often attenuated the

capital flows.

The large gross external asset positions among

today’s advanced countries with floating

exchange rates have little precedence in the

past, which suggests that exposure to market and

exchange rate risks during external adjustment

may be quite different. Nevertheless, with large

imbalances in both eras of financial globalization, the earlier era may still provide relevant lessons. Most prominently, the generally

remarkably smooth adjustment among the countries adhering to a stable and credible nominal

anchor—the gold standard—underscores the

important role of well-functioning and credible

nominal anchors and sound financial policies in

facilitating external adjustment.

119

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

Box. 3.2. Measuring a Country’s Net External Position

The net external position of a country is the

difference between the country’s external

assets—the claims of a country’s residents on

nonresidents—and its external liabilities—the

claims of nonresidents on residents. These

claims are divided in broad categories, which

correspond to those in balance of payments

statistics: foreign direct investment; portfolio

equity securities; portfolio debt securities;

other assets and liabilities (such as bank loans,

trade credits, and currency deposits); and

financial derivatives.1 A country’s claims on

nonresidents also include the reserve holdings

of the central bank, which are classified separately. Gross external debt is given by the sum

of portfolio debt liabilities, debt liabilities in

the direct investment category, and other

liabilities.

Until a few years ago, data on external assets

and liabilities (the so-called International

Investment Position, or IIP) were reported by

most industrial countries and few emerging

markets. In recent years the number of reporting countries has increased exponentially and

now totals about 100 (even though coverage

for newly reporting countries is typically

limited to the most recent period). The data

used in this chapter, constructed by Lane and

Milesi-Ferretti (2001, 2005b), combine country

estimates of external assets and liabilities (as

reported in their IIP) with estimates from

alternative sources (such as the World Bank’s

debt database for external debt liabilities) or

based on cumulative capital flows with appropriate valuation adjustments. The data cover 87

countries, including virtually all advanced

Note: The main author of this box is Gian Maria

Milesi-Ferretti.

1The FDI category reflects a “lasting interest” of an

entity resident in one economy in an enterprise resident in another economy (IMF, 1993). This includes

greenfield investment as well as significant equity participation (typically set at above 10 percent), while

remaining holdings of equity securities are classified

under portfolio equity investment. This implies that in

certain cases the distinction between these two categories can be blurred.

120

and emerging economies, for the period

1970–2003.2

How do valuation adjustments work? For

example, in the absence of information on foreigners’ holdings of domestic equities, these

can be approximated by cumulative net foreign

purchases of domestic equity (which can be

obtained from the widely available balance of

payments data), adjusted each year for the

change in the value of existing liabilities due to

fluctuations in stock prices and exchange rates.

These fluctuations in value, which can be

approximated by the variation in a domestic

stock price index, are not reported as investment returns in balance of payments statistics,

which for equities only record the flow of

dividends.3

As external assets and liabilities grow, these

valuation changes become quantitatively very

important—indeed, as discussed in the text, the

relationship between the current account and

the dynamics of the net external position has

substantially weakened in recent years. For

example, the U.S. net external position in 2003

was broadly unchanged as a ratio of GDP, since

the large current account deficit was offset by a

correspondingly large valuation gain, generated

by increased dollar values of U.S. foreign assets

as the dollar depreciated.

Valuation changes for portfolio equity and

FDI can be particularly large. For example,

between end-1998 and end-1999 the stock of

2A significant earlier contribution is Sinn (1990),

who constructs estimates of external assets and liabilities for the period 1970–87 for an even larger sample

of countries.

3Estimating valuation adjustments for the foreign

assets of a country is a more complex endeavor. A

precise calculation would require information on

the geographical and currency distribution of the

country’s claims, which is available for only a few

countries and typically for recent years. In the

absence of such information, one can for example

assume that the geographical distribution of assets follows the country’s trade pattern, or, for stock or bond

markets, relative market capitalization in the rest of

the world.

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

Finnish portfolio equity liabilities increased

from about US$80 billion to about US$220 billion, even though net purchases by foreigners

during 1999 amounted to only US$10 billion!

The underlying cause for this valuation change

was the boom in the price of Finnish stocks—

particularly Nokia—during 1999.

Particular difficulties are posed by the valuation of foreign direct investment. Most countries

report the book value of their direct investment

assets and liabilities, while others, such as

France, Sweden, and the United States report

estimates both at book and at market value. The

difference can be significant, especially when

corporate valuations change substantially.

Finally, coverage of derivatives’ contracts in

international statistics is still very spotty, thereby

limiting our knowledge on the extent of crosscountry hedging.

With data on the stocks of external assets and

liabilities and the underlying capital flows, it is

possible to calculate the rate of return that a

country earns on its external assets and pays out

on its liabilities. These returns can be calculated by adding the yields on external claims

(which are measured as investment income

flows in the current account) and the capital

gain (which can be approximated by the difference between the change in value of the claim

and the underlying capital flow). On average,

rates of return are larger and more volatile

than yields, reflecting the fact that a significant

component of equity returns takes the form of

capital gains, rather than dividends (see the

figure).

The availability of comprehensive data on

external positions has enabled researchers to

address a number of important issues in international macroeconomics, including the determinants of long-run net external positions (Lane

and Milesi-Ferretti, 2002b), the link between net

current account deficit, which could facilitate

adjustment in production structures in the

United States and other countries and, thereby,

reduce the size of the overall exchange rate

United States: Rates of Return and Yields

on Foreign Assets and Foreign Liabilities

(Percent 1983–2003)

Foreign Assets

30

25

Return

20

15

10

Yield

5

0

-5

1983

88

93

98

Foreign Liabilities

-10

2003

30

25

20

Return

15

10

5

Yield

0

-5

1983

88

93

98

-10

2003

Source: IMF staff calculations.

external positions and real exchange rates

(Lane and Milesi-Ferretti, 2004b), and changes

in the extent of international risk sharing (Imbs,

2004; Huizinga and Zhu, 2004). Also, the sum of

external assets and liabilities has been used as a

volume-based measure of international financial

integration when studying the effects of integration on macroeconomic performance (see, for

example, Edison and others, 2002; and Prasad

and others, 2003).

adjustment (Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2000). On the

other hand, this opportunity could also turn

into a liability if macroeconomic policies do not

remain consistent with a credible medium-term

121

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

Box 3.3. Financial Globalization and the Conduct of Macroeconomic Policies

Note: The main author of this box is Irina Tytell.

122

Financial Globalization and

Macroeconomic Policies1

Log Inflation

6

4

2

0

0

100

200

300

400

Log inflation, percent a year

8

-2

500

Gross foreign assets and liabilities, percent of GDP

Budget Deficit

8

6

4

2

0

-2

-4

0

100

200

300

400

Budget deficit, percent of GDP

Macroeconomic policies around the world

have improved over the past two decades. The

average budget deficit across both industrial and

developing countries has declined from approximately 5 percent of GDP during the late 1970s

to just over 2 percent of GDP recently. Similarly,

with monetary policy increasingly focused on

inflation control, inflation rates have been

decreasing across the globe.

A widely quoted explanation for these developments is that financial globalization has

exerted a disciplinary effect on the conduct of

policies, because international capital flows

adversely respond to imprudent macroeconomic

policies (e.g., Fischer, 1997; or Stiglitz, 2000).

This explanation is not universally accepted,

however, and some have argued that global

financial markets fail to discipline policies (e.g.,

Rodrik, 2001). Against this background, this box

reexamines the foundations of the hypothesis of

the disciplinary effects of financial globalization

and assesses its empirical merits.

From a theoretical perspective, the incentives

for host governments to conduct good policies

depend on their rewards and costs. To the

extent that good policies attract capital flows

that help raise the domestic capital stock, the

associated higher output is the reward. The

costs of good policies to policymakers are

related to political economy considerations.

For example, the need to conduct prudent

fiscal policy can limit politicians’ scope for discretion related to their own narrow interest. If,

on balance, the rewards are large enough to

offset the costs, globalization will indeed be a

disciplinary device. This in turn suggests two

conclusions.

• The disciplinary effect of financial globalization may be stronger for some policies and

weaker for others. In particular, if prudent fiscal policy exerts higher political economy

costs than, say, monetary policy, one would

expect the disciplinary effects of globalization

to be stronger for monetary policy.

-6

500

Gross foreign assets and liabilities, percent of GDP

Sources: Tytell and Wei (2004); and IMF staff calculations.

1For the period 1990–99.

• A critical issue regarding the benefits of capital flows concerns the possibility of changes in

investor sentiments in international capital

markets that are reflected in capital flow fluctuations unrelated to policies or developments in the host country. Through their

potential to lower the benefits of good policies, they tend to weaken the disciplinary

effect on policy conduct.

What does the empirical evidence for the

recent era of globalization look like? A simple

inspection of the relationship between a measure of financial globalization—the ratio of gross

foreign assets and liabilities to GDP—and inflation rates and budget balances suggests the following (see the figure).

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

• The relationship between inflation and the

extent of financial globalization is generally

negative.

• The relationship between budget deficits and

financial globalization is markedly weaker.

Such bivariate relationships can, of course, be

misleading, since they do not control for other

determinants of macroeconomic policies or

other dimensions of globalization. For a more

complete analysis, Tytell and Wei (2004) used

two different econometric approaches.1

First, inflation rates and budget balances

were simultaneously regressed on financial

globalization (ratio of foreign assets and liabilities to GDP) and a number of other relevant

variables, including indicators of exchange rate

flexibility, central bank independence, government fragility and polarization, and trade openness. To isolate the effect of globalization on

policies while mitigating problems of reverse

causality (and measurement errors), the

authors focused on the common component

of international capital flows to countries in

the same geographic region. The results confirm that the coefficient on financial openness

in the inflation equation is negative and statistically significant (although fairly small in

magnitude). The same coefficient in the equation for budget balances is statistically insignificant. These results are robust to various

alternative specifications, different measures of

financial openness, and alternative instrumental

variables.

Tytell and Wei also use thresholds to classify

policies as “good,” “moderate,” or “bad,” to control for the fact that small fluctuations in inflation rates or budget balances are unlikely to

1The study covers a sample of 62 industrial and

developing countries, which excludes major oil producers and very small countries.

policy framework aimed at external and internal

balance. In this regard, it is important to note

that globalization may not be as effective a disciplinary device for the conduct of macroeco-

reflect changes in policymakers’ attitudes.2 This

allows an investigation of whether the disciplinary

effects differ depending on the economic situation and whether they work by inducing policy

shifts between different states rather than affecting policies within a given state. The results lend

support to the view that financial globalization has

a positive and statistically significant effect on the

probability of inflation decreasing from “bad” to

“moderate” and from “moderate” to “good” and

a negative effect on the probability of inflation

increasing from “good” to “moderate.” In contrast, the results do not provide support for the

view that financial globalization exerts a disciplinary effect on government budgets.

Overall, while plausible from a theoretical

perspective, the empirical evidence for the

hypothesis that financial globalization exerts a

disciplinary effect on the conduct of macroeconomic policies is rather mixed. There does

appear to be a significant, albeit small, impact

on monetary policy, but little on fiscal policy.

This suggests that relying on financial globalization to act as a device for ensuring policy discipline is not enough. It also suggests that other

factors must have played a role in the observed

improvement of macroeconomic policies, some

of which may have been related to globalization,

although through channels other than the one

discussed here. In this light, Box 3.4 examines

the link between globalization and monetary

policy from a broader perspective.

2The thresholds are based on the relevant literature.

For example, there is some agreement in the growth

literature that inflation rates beyond 7 to 11 percent

hurt growth in developing countries (e.g., Khan and

Senhadji, 2000). Hence, inflation rates of 10 percent

or less are classified as reflecting “good” monetary policy while inflation rates above 40 percent—a widely

accepted benchmark for high inflation—are classified

as “bad” policies.

nomic policies as is widely thought (see Box 3.3

for recent empirical evidence on the disciplinary effects of financial globalization on macroeconomic policies).

123

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

Valuation Effects and External Adjustment

Figure 3.5. Valuation Effects on Net Foreign Assets

(Percent of GDP)

For larger industrial countries, annual valuation changes have become greater in

the 1990s, even if the cumulative sums shown below tend to be small due to the

frequent change in sign. For emerging market countries, magnitudes of valuation

effects have generally increased over the past decade.

1982–92

1993–2003

Selected Industrial Countries: Median of Annual Valuation Changes

(absolute values)

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

e

n

a

a

s

n

n

ly

y

d

m

ds

do trali Franc anad Spai Japa State rman Ita

ede land lan lan

C

Sw Fin ether itzer King Aus

e

d

G

e

t

w

i

d

N

S

ite

Un

Un

Selected Industrial Countries

(absolute values of cumulative change)

0

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

d

ds and

lan lan

l

Fin ther itzer

e

N

Sw

lia Italy pan

en om ce

ny

ain

tes da

Sp Sta Cana rma wed ingd Fran ustra

Ja

e

S

d

K

A

e

G

t

i

d

ite

Un

Un

Selected Emerging Market Countries

(absolute values of cumulative change)

40

30

20

10

a

zil

bia ay Chile guay

t i n ico

en Mex Bra lom rugu

ra

U

Arg

Pa

Co

a

s sia rea

nd

ne

esi

on aila ppi alay Ko

M

I n d T h Phili

0

Sources: IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics; Lane and MiIesi-Ferretti (2005b); and IMF

staff calculations.

124

A critical, and often underappreciated, implication of recent financial globalization is that

with both foreign assets and foreign liabilities rising sharply, investors—and countries—are much

more exposed to capital gains and losses owing

to exchange rate and other asset price changes.18

For example, if all foreign assets are denominated in foreign currency, a 10 percent exchange

rate depreciation increases their domestic currency value by 5 percentage points of GDP if the

stock of assets is 50 percent of GDP and by 10

percentage points if it is 100 percent. Higher

gross positions also tend to generate larger valuation changes in net foreign assets, although

structure and relative size of assets and liabilities

also matter.

IMF staff estimates of valuation changes in

industrial and key emerging market countries

confirm that as a percent of GDP, annual and

medium-term19 valuation changes in net foreign

assets generally increased in magnitude during

the 1990s compared with the 1980s (Figure 3.5).

The increase in medium-term valuation changes

is particularly noteworthy in some smaller and

relatively more open industrial countries that

have seen rapid changes in gross or net positions

(e.g., Finland, the Netherlands, and Switzerland)

and in emerging market countries, particularly

those that have faced large, one-off changes in

exchange rates (e.g., Asian emerging market

countries during the 1997–98 financial crises).

In other countries, however, magnitudes have

decreased, including in those that experienced

larger exchange rate changes in the 1980s compared with the 1990s.

An important implication of persistent valuation changes is that external current account

surpluses or deficits could become relatively less

important determinants of net foreign asset positions (Obstfeld, 2004), as illustrated by the expe-

18See Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2001, 2005a), Tille

(2003, 2004), Gourinchas and Rey (2004), and Obstfeld

(2004).

19Defined as the cumulative sum over a 10-year period.

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

rience of a number of industrial and emerging

market countries during the 1990s (Figure 3.6).

A key question, of course, is whether valuation

effects can help in external adjustment. Given

the prominent role of exchange rates in this

regard, the focus will be on the exchange-raterelated valuation effects. (Historically, valuation

effects arising from other asset price changes

have also been large in some cases, including

during times of sharply reduced asset return correlations.) Two factors are important in this

regard. First, the nature of the exchange rate

changes matters. If they are unexpected, valuation effects on net foreign assets are lasting,

while those associated with anticipated changes

are not, because the latter tend to be reflected

in asset yields, which, in turn, offset the valuation effects through their impact on current

accounts.20

Second, the general structure of external

assets and liabilities—especially their currency

composition but also the nature of the underlying financial instruments—also plays an important role in determining whether valuation

effects contribute to external adjustment.

• In industrial countries, where foreign assets

tend to be denominated in foreign currency

and liabilities in domestic currency, valuation

effects arising from unexpected exchange rate

changes—including those related to portfolio

preference disturbances—tend to facilitate

adjustment because they can provide for burden sharing among countries. In countries

with currency depreciation, the domestic currency value of foreign assets increases and—

with the value of liabilities unchanged—net

foreign assets improve; the reverse takes place

in countries with appreciating currencies. If

Figure 3.6. Valuation Effects, Current Accounts, and Net

Foreign Assets

In the 1990s, the contribution of valuation effects to changes in net foreign assets

was large relative to current account balances, especially in small open industrial

economies and east Asian countries. More generally, the correlation between

changes in net foreign assets and current account balances weakened.

Selected Industrial Countries: Current Account and Valuation Effects

Contribution to Changes in Net Foreign Assets (NFA), 1993–2003

(percent of GDP; cumulative changes over period indicated)

United States

Current accounts

Japan

Valuation effects

Canada

United Kingdom

Germany

France

Italy

Netherlands

Spain

Ireland

Finland

Norway

Sweden

Switzerland

Australia

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

120

Selected Emerging Market Countries: Current Account and Valuation

Effects Contribution to Changes in NFA, 1993–2003

(percent of GDP; cumulative changes over period indicated)

Current accounts

Argentina

Brazil

Valuation effects

Mexico

Chile

Colombia

Uruguay

Paraguay

Korea

Indonesia

Philippines

Malaysia

Thailand

China

India

Turkey

-50

-40

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

40

Rolling 10-Year Correlation Between Changes in NFA and Current

Accounts (averages by country groups)

Emerging Asia

Latin

America

50

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

Industrial

countries

20See Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2005a) and Obstfeld

(2004). Consider, for example, the case of an anticipated

depreciation from the perspective of a foreign bond

investor. Assuming unchanged risk preferences, the lower

value of the principal (in foreign currency) due to the

depreciation requires higher yields to preserve the present value of the investment. With anticipated exchange

rate changes, return adjustments may be amplified by

portfolio reallocation.

100

0.2

0.0

1985

90

95

2000

-0.2

Sources: IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics; Lane and MiIesi-Ferretti (2005b); and IMF

staff calculations.

125

CHAPTER III

GLOBALIZATION AND EXTERNAL IMBALANCES

Figure 3.7. Valuation Changes in Net Foreign Assets

and Real Effective Exchange Rates

Valuation effects on net foreign assets facilitated the external adjustment in the

mid-1980s (as indicated by the ellipses).

Valuation changes (percent of GDP; left scale)

Real effective exchange rate (+ = depreciation; 2000 = 100; right scale)

4

United States

2

180

4

160

2

Euro Area and Japan

160

140

0

140

0

120

-2

120

-2

100

-4

-6

4

1980 85

90

95 2000

Emerging Asia

100

80

-4

60

-6

120

4

110

2

80

1980

85

90

95 2000

Rest of the World

-2

-6

100

90

90

80

-2

80

60

1980 85

90

95 2000

120

0

70

-4

60

110

2

100

0

180

50

70

-4

-6

60

1980

85

90

95 2000

50

Sources: IMF, Balance of Payments Statistics; Lane and MiIesi-Ferretti (2005b); and IMF

staff calculations.

126

the direction of exchange rate changes

matches that of external adjustment—that is,

currency depreciation in countries where

external balances have to improve (deficit

countries) and appreciation in other countries—this is equivalent to a wealth transfer

from surplus to deficit countries, which, everything else being equal, can help reduce the

amount of trade adjustment needed (see

Appendix 3.1).21 This mechanism was evident

during the U.S. current account correction of

1985–88, when the U.S. dollar depreciated by

about 30 percent in real effective terms

(Figure 3.7).22 More recently, the valuation

adjustments associated with the U.S dollar

depreciation during 2002–03 have offset about

three-fourths of the cumulative U.S. current

account deficit over the same period.

• In emerging market countries, where some

foreign liabilities, especially debt liabilities,

tend to be denominated in foreign currency,

valuation effects from unexpected exchange

rate depreciations are likely to complicate

external adjustment, given the increase in the

domestic currency value of these liabilities. On

the other hand, currency appreciation tends

to have positive valuation effects and improve

net external positions, as illustrated in Figure

3.8 for selected Latin American and East Asian

countries.

For a systematic assessment of the role of the

valuation channel in external adjustment, IMF

21It is, of course, possible to hedge at least partly against

valuation effects by using financial derivatives, which may

reduce the real impact of valuation effects, including

those arising from the wealth transfer from surplus to

deficit countries. This depends importantly on whether

the hedging is undertaken within countries or across

countries. In the case of the former, there are no aggregate hedging gains or losses at the country level because

the gains from hedging for some residents are offset by

hedging losses of other residents, and valuation effects

have real aggregate effects. Cross-border hedging activities, however, affect the real impact of valuation changes.

22If the currency realignment of the mid-1980s had

involved today’s larger gross positions, U.S. valuation

gains would have been more than twice as large as those

in the 1980s, while the losses in Japan and the euro area

countries would have been three times as large.

FINANCIAL GLOBALIZATION

staff undertook an econometric investigation of

the recent experience of 49 countries—21 industrial and 28 emerging market and developing

countries—for the period 1970–2003 (see

Appendix 3.2 for details and documentation of

the results). Following Gourinchas and Rey

(2004) and Corsetti and Kostantinou (2004), the

approach was to examine the dynamic responses

of trade balances (defined as the sum of net

exports of goods and services) and net foreign

assets to external imbalances. The intuition

behind this approach is as follows. Because countries must ultimately be able to pay their debts—

the so-called intertemporal external budget

constraint—trade balances and net foreign assets

are tied together in the long run. For example, a

debtor country will need to have a trade surplus

in the long run that is large enough to cover the

cost of its net external liabilities.23 While trade

flows and net foreign assets can deviate from this

long-run relationship in the short term, over

time that relationship has to be restored through

an adjustment in net exports, in net foreign

assets (other than the changes arising from the

adjustment in net exports), or a combination of

both. If a significant part of the adjustment

occurs through changes in net foreign assets, this

is interpreted as evidence for the valuation channel contributing to external adjustment. The

results can be summarized as follows.

• For the majority of emerging market countries, adjustment came entirely through trade

(net foreign assets were not found to respond

to deviations from the long-run relationship

between the trade balance and net foreign

assets). This finding does not mean that valuation effects are unimportant in these countries. On the contrary, the results imply, for

example, that negative valuation shocks, such

as those from a depreciation of the exchange

rate, tend to permanently worsen net foreign

asset positions in these countries and the

Figure 3.8. Selected Emerging Market Countries:

Valuation Changes and Real Effective Exchange Rates

Exchange rate depreciations tend to have adverse valuation effects in emerging

market countries.

Valuation changes (percent of GDP; left scale)

Real effective exchange rate (+ = depreciation; 1990 = 100; right scale)

40

Argentina

200

30

200

150

150

0

10

0

100