Document 11816154

advertisement

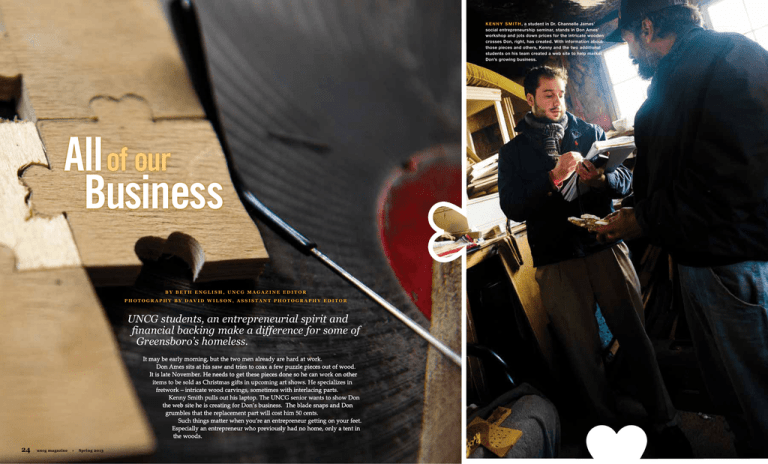

K E N N Y S M I T H , a student in Dr. Channelle James’ social entrepreneurship seminar, stands in Don Ames’ workshop and jots down prices for the intricate wooden crosses Don, right, has created. With information about those pieces and others, Kenny and the two additional students on his team created a web site to help market Don’s growing business. All of our Business BY BETH ENGLISH, UNCG MAGAZINE EDITOR PHOTOGRAPHY BY DAVID WILSON, ASSISTANT PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR UNCG students, an entrepreneurial spirit and financial backing make a difference for some of Greensboro’s homeless. It may be early morning, but the two men already are hard at work. Don Ames sits at his saw and tries to coax a few puzzle pieces out of wood. It is late November. He needs to get these pieces done so he can work on other items to be sold as Christmas gifts in upcoming art shows. He specializes in fretwork – intricate wood carvings, sometimes with interlacing parts. Kenny Smith pulls out his laptop. The UNCG senior wants to show Don the web site he is creating for Don’s business. The blade snaps and Don grumbles that the replacement part will cost him 50 cents. Such things matter when you’re an entrepreneur getting on your feet. Especially an entrepreneur who previously had no home, only a tent in the woods. 24 uncg magazine ° Spring 2013 Spring 2013 ° uncg magazine 25 All of our Business He also wants to teach others some part of what he has learned through the years. He thinks it can help in more ways than one. He shares the story of a stroke victim who started doing fretwork, which helped retrain his brain. For now, students are helping Don with marketing while he focuses on his artistry. V A R I O U S F R E T W O R K P I E C E S – from tree ornaments to a clock stand (far left) – lie on a bench in Don Ames’ workshop while Don and Kenny Smith take inventory and discuss pricing. B E L O W R I G H T , Kenny shows Don the web site his team is working on to help Don’s business and asks for his feedback. Don relies on solar panels to power his tools, eliminating the need for electricity. Inside the workshop, the only heat comes from a camping stove. As the men talk, their breath steams in the air. “I want to show you the site to get your feedback,” Kenny says. He points to a space built in for testimonials and describes menu buttons for how to contact Don, shipping information, Q&A, a blurb explaining this 200-year-old fretwork process. “I know you have a Yahoo email account, but I started a Gmail account for you.” Kenny explains that it will enable him to use Google Plus, so he can plan events, share new products, upload files, create contact lists. “It’s so easy, Don. It’s going to help you so much.” “Outstanding,” he replies. The meaning behind the words “social entrepreneurship” might be a little vague to some folks, but to Dr. Channelle James ’04 PhD, those words are powerful. “I’ve always had a passion for social issues, women’s issues, community issues,” says the business professor. Social entrepreneurship blends business with serving the community in some way. Social entrepreneurs use market forces to create social good. Her students are learning what it means first-hand. For several years, Channelle has taught a seminar on social entrepreneurship to undergraduate students. They cover basic entrepreneurship topics such as defining the market, creating business plans and finding the break-even point just like in a normal entrepreneur class. The difference is students use this knowledge to focus on critical 26 uncg magazine ° Spring 2013 social issues that make an impact on the community. Previously, students had been required to find their own projects to complete their coursework. That changed in 2011, when two local retired businessmen, Pete Pearce and Ernie Manuel, hatched a plan to put their years of experience to use while helping the homeless get back on their feet. Channelle was at the Bryan School when they came by, looking for help to carry out their plan. The Bryan School, with its growing reputation in entrepreneurship, seemed like a natural fit. They brainstormed together and reached out to the Interactive Resource Center, a day center for those struggling with homelessness. The IRC found five people with entrepreneurial dreams and Channelle matched them with small groups of students to start the program. Over the course of two to three months, the students and entrepreneurs met and planned. In December, they presented those plans to Pete, Ernie and Liz Seymour, executive director of the IRC. Based on the pitches of the first group of entrepreneurs, Pete and Ernie decided whether to back them with small loans – generally $150 to $300. The entrepreneurs were expected to set up a payment plan to repay the loans. Don Ames was in the first group of entrepreneurs. The minute he got his loan, he invested in solar panels so he could power his tools without electricity and bought an additional saw for cutting intricate patterns. A year later, he’s in a home but he’s still working on getting the business to grow. He has dreams. “My ultimate goal is to get out of here (this neighborhood) – go someplace more presentable for customers,” he says. “Maybe have a storefront.” During his visit to Don’s workshop, Kenny also wants to cover inventory and pricing. His team members are working on a catalogue and a short biography of the woodworker. Don pulls woodwork out of a red, nylon bag. Kenny makes notes about each one. First is the phrase “Gone crazy, back soon” carved in wood. Don prices that at $10. He pulls more pieces from the bag, naming them and a price. Dainty wall shelf, $65. Heart shaped box, $30. Joy cross (bearing the words “May the God of joy give you love and peace”), $25. Kenny takes a good look at that one. “I might buy that from you for my mom,” he says. Intricately carved ornaments follow. $15 each or $45 for a set of four. A cross stained with tung oil is priced at $15. He has six of those. An unfinished cross is also $15. “That’s a good value,” Kenny says. “You could do an extra $5 for the finish.” Jewelry chest, $35. Kenny asks him about what appears to be woven wood on the side of the chest. “I don’t give all my secrets away,” Don jokes. Next is the puzzle clock – a time piece inside a circular jigsaw puzzle. “I tell people $45 for the clock, $60 if you want it assembled.” Then they move on to the bigger items. Table clock, $250. He shows the side panel of what will become a 3-foot replica of Big Ben. That’s $750. Each piece can take him anywhere from a few hours to a few days to create. He’s working on six puzzles, which, once delivered, will give him enough income to buy a phone card and maybe another solar panel. He and Kenny had a hard time making contact earlier in the semester. “This is my only source of income,” Don says, gesturing to the wood on the jigsaw. “My phone was out.” As he prepares to leave, Kenny asks about meeting up again. Sunday would work for him. Don shakes his head. “On Saturdays and Sundays at 8, the homeless meet up at Center City Park. I go and help out,” he says. They agree to meet Monday. Kenny is optimistic he will have the web site almost ready to launch. A B O V E Don Ames shows his puzzle clock – a timepiece surrounded by a circular wooden jigsaw puzzle. Kenny Smith and Don Ames wave good-bye as they leave the workshop. The entrepreneurs selected to work with the students must apply and go through a vetting process. The program doesn’t take on those who are too advanced or those who really aren’t in a position to work as an entrepreneur, Channelle says. It has to be the right fit. Because of the population they’re working with, they don’t like to put people on a waiting list. This year, they had more applicants than student groups. So Channelle herself worked with one of their continuing entrepreneurs, Leddie Miller. She’s marketing herself as the “greener cleaner.” Leddie has worked with three sets of students fine-tuning her message to get more housecleaning jobs. She’s loved working with them. “I got attached to them,” she says. “They still email me and I email them back.” That connection between student and entrepreneur is at the heart of this course. “The students learn about social issues of employment, “Business can make a difference. This program has so many wins. I haven’t figured out one wrong thing with it.” — Dr. Channelle James Spring 2013 ° uncg magazine 27 All of our Business creating business plans and how to present in front of people with great experience,” Channelle says. “Sometimes it’s easier to learn when you’re working on something for someone else.” In addition to putting their business skills to work, students learn about homelessness. “People think that what they see on the street is all there is,” she says. “It has stages. From losing a job and having to stay on the couch of a family member to the chronically homeless. They are people just like us. Students learn it can happen to anyone.” Liz hears something similar when she talks with students. “They come in with this picture in their mind of the person they will be working with and they find it’s not at all like that.” On the night before final presentations, Dao Her, a senior majoring in business administration, waits in Jackson Library to meet up with her entrepreneur. Eventually, she calls the entrepreneur to find out she isn’t coming because her mother is ill. It’s a bit of a setback, but Dao tries not to worry. Their group has done their research. The entrepreneur’s business is creating unique gift baskets. Each student is expected to contribute 20 hours to the business and their group has created three types of business cards, a flyer and a web site with photos of her work. They also did price comparisons at Wal-Mart and Michaels, and looked into ways to wrap the baskets differently. “We’ve suggested that she create a prototype but, to her, she likes that each one is unique,” Dao says. “It’s up to her.” As a full-time research analyst at Lincoln Financial, Dao had no idea the class she signed up for would be so time-intensive. But it was worthwhile, she says. “I had never thought about social entrepreneurship,” she says. “It’s quite interesting. There’s the warm feeling that I’m helping someone else. It shined a new light for me, a new thought about homelessness. How can someone like this be in this situation?” “Homelessness is not for the weak of heart,” Liz says. “You have to have resilience, a strength of purpose to keep going when things are stacked against you.” One of the things the entrepreneurs like about the class is the energy and enthusiasm the students bring – that and knowing someone believes in you, Liz says. Sitting on the panel for the presentations, she witnesses how the businesses progress. “Sometimes the business is not a success but the experience was a success.” She and Pete and Ernie had met with the student groups two weeks before, talking through the business plans and offering advice before the final presentations. One group was working with a carpenter. Another, a landscaper who had trouble with transportation because his license was revoked. Another group was working with a stone mason. 28 uncg magazine ° Spring 2013 D O N A M E S reaches into one of his creations, a miniature cathedral. Liz Seymour, IRC executive director, purchased the piece a while ago and displays it in her office. At the DECEMBER CR AFT FAIR at the Interactive Resource Center, customers pause by a small Christmas tree filled with Don Ames’ fretwork ornaments. The largest group, by far, was for a new model – an artist’s co-op called ArtiFacts. Channelle is enthused about it for a practical reason – it can serve several entrepreneurs with one business model. Liz likes it for another reason. “What I love about art – you don’t say, ‘Oh, look at what the homeless person did.’ You say, ‘That’s a nice piece of art.’ We have a lot of talented artists here. It makes sense to have a collective way to market and sell the art.” The talk that day was about a craft fair planned for mid-December at the IRC. The students had created a database to keep track of the artists and their fees. One of the biggest issues they noticed was cost. Artists either overpriced or underpriced their items. It’s something Channelle has seen before. “Entrepreneurs sometimes feel like what they’re producing is not worth a higher price because of who they are,” she says. On the day of the craft fair, three of the group members arrive early to help set up tables, make signs and organize a way to ensure each artist gets paid at the end of the fair. “I’ve always wanted to give back. When we serve more, it puts things in perspective,” says Maria-Elena Henry, a senior majoring in dance and minoring in entrepreneurship. One entrepreneur, Juanita Moravian-James, arranges beaded necklaces and earrings on a table covered with a red cloth. On the table to the right of her, Leddie Miller creates a display with her green cleaning supplies. Don Ames comes in a short time later and stands a 2-foot Christmas tree on his table. Juanita helps him fluff the branches and hang his wooden ornaments. Other tables feature drawings, origami and beautifully crocheted blankets and scarves. When opening time comes, people filter in and linger by the tables. At the front, student Hannah Miller takes money, writes down what has sold and gathers email addresses for the future. She loves this part – the organizing and seeing a project come to fruition. At the end of three hours, they are thrilled to realize the entrepreneurs made $550. Spring 2013 ° uncg magazine 29 All of our Business At the final presentations, Ernie, Liz and Pete listen intently as students in business attire, accompanied by the entrepreneurs, walk through PowerPoint presentations listing the target markets for their entrepreneurs, their recommendations for how to move the businesses forward and what kinds of critical issues lay ahead. They explain how the funds will be used. Michael Mayo, a stone mason, opens the pitch for his business. “I need the funds to start my own company,” he says. “I have done this type of work for 23 years. My work is quality work. I lay it one time and it’s done.” He requests enough money to buy the basics – trowel, mortar pans, wheelbarrow, level, hoe. “He already has the skills,” says student Rashid Muhammed. “He just needs the opportunity.” During Don’s presentation, Kenny – along with classmates Brittany Wilkins and Nicola Ross – explain what they have done for his business. They demo the web site, show a catalogue they created and talk about his target market – baby boomers. 30 uncg magazine ° Spring 2013 H A N N A H M I L L E R , a senior who worked on the artist co-op ArtiFacts, spreads a brightly colored fabric over a table for an artist to display her work. Her group organized this craft fair at the IRC so that several artistic entrepreneurs could sell their products, whether jewelry, drawings, origami or crocheted blankets. U P P E R R I G H T , Liz Seymour, center, talks with students Hannah Miller, right, and Maria-Elena Henry, left, during the craft fair. B E L O W R I G H T , Juanita Moravian-James celebrates getting a loan to continue working on her jewelry business. “His work is one of a kind and meant to last generations,” Kenny says. “We’re offering a lifetime product.” He is asking for money to buy more solar panels so Don can work longer hours. “Don is definitely a work horse,” Kenny says. “Each panel is $150, and he needs five of them.” Liz is interested in the web site. “Don, can you update this web site?” “I believe I can manage that,” he replies. She and the others worry a bit about Don getting deluged with orders. “You’ve got to execute,” Pete says. “I’ve got my work cut out for me,” Don agrees. But he tells them he plans to check email at 4 a.m. and can ship orders from the post office, which is only six blocks away from his home. The rest of the time will be dedicated to fretwork. Kenny has to leave for an exam so only Nicola and Brittany remain as Don packs up his inventory. He stops them at the back of the conference room, holding out a wooden ornament for each student. They oooh and ahhh and thank him. “Thank you,” he says. g UNCG at the IRC Students from Dr. Channelle James’ class aren’t the only ones involved with the Interactive Resource Center. When Channelle first went to the day center for Greensboro’s homeless, she found UNCG connections all over. Here’s a partial listing of ways UNCG faculty, students and staff have invested in the center: • Since 2009, social work students with the congregational social work educational initiative – a joint program between UNCG and NC A&T – have interned at the IRC, doing intakes and case meetings. “It’s a great relationship, a great alliance,” says Liz Seymour, executive director of the IRC. • Students working with the Speaking Center come to the IRC to help clients prepare for job interviews. They tape a mock interview and then review it with the client and give feedback. • Dr. Elizabeth Chiseri-Strater, a UNCG professor of English, is chief editor of The Voice, a newspaper written by those at the IRC. It covers such issues as mental health, how it feels to be homeless and challenges people at the IRC often face. • MFA students teach creative writing classes there as part of Write-On Greensboro. • A VISTA student from the Office of Leadership and ServiceLearning spends 30 percent of her time at IRC. Her charge: food security. She masterminded the small garden in front of the center. • Last spring, the theatre production “In the Blood” featured a single, homeless mother as a character. The class came over to talk with some clients to understand the role better. • Students also come to fulfill other kinds of internships or to learn more for research papers. Postcript T H E G I F T B A S K E T E N T R E P R E N E U R Dao Her and her group worked with did not get a loan but will remain in the program to further develop her business plan. J U A N I T A M O R A V I A N - J A M E S did get a loan and will work with a student group to further plan her business this spring. M I C H A E L M A Y O did not receive a loan. The group thought Michael’s plan might be too risky in a competitive construction industry and did not want to set him up for failure. They believed Michael would be better off working for someone else until he could get better established. A R T I F A C T S received a mini-loan to help further develop the cooperative and to buy supplies so artists can continue their work. D O N A M E S , L E D D I E M I L L E R and S A M K W A R T E N G had previously received loans and will continue working with students to develop their businesses and paying back their loans. This spring, new entrepreneurs have been added to the program. And the students, if they’re anything like their predecessors, will feel the impact of this class long after they graduate and move on. Channelle recalls a summer Saturday when she went to the IRC for a fundraising car wash. “When I pulled my dirty little car up, I saw Matthew Puzio.” He had graduated in May but came back to volunteer. “That meant a lot.” Another student, Andres Bueno, helped present the ArtiFacts model at the UNC Social Business competition in September, even though he finished her class the previous year. “Bryan School students are committed to the community and to positive social change.” Spring 2013 ° uncg magazine 31