Document 11760274

advertisement

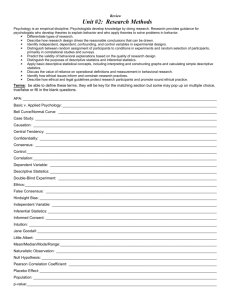

00 • wo psyc 00 SCOTT SEIDER, KATIE DAVIS GARDNER and HOWARD with a new paradigm for considering ethical dilemmas and quality in psychology. HEN a scholarly discipline involves human beings - as researchers or subjects, as clinicians or patients - ethical issues are certain to loom large. On the research dimension, famous social psychological studies by Stanley Milgram on obedience to authority and Philip Zimbardo on abuse of authority sparked widespread debate about the proper treatment of participants. Claims in The Bell Curve (Hermstein & Murray, 1994) about heritable differences in lQ across racial groups ignited heated debate about whether some scholarly investigations should be avoided altogether. Complementing such flare-ups in the research community are perennial ethical issues involving treatment. A 1988 survey of dilemmas encountered by practising psychologists turned up the following issues: disclosure of confidential information, inappropriate or other conflicting relationships with clients, providing services to those unable to pay, appropriate advertisement and representation of credentials, and the conduct of colleagues and publication credit (Pope & etter, 1988). These dilemmas are not restricted to the consulting room. Bloche and Marks (2005) report that the United Stales military prison for suspected terrorists at Guantanamo Bay W WEBLINKS The GoodWork Project: www.goodworkprojeetorg Institute for Global Ethics: www.globafetiJics.org APA Ethics Office: www.apa.org/eliJics ~-------------- I The Psychologist Vol 20 No II employs teams of psychologists to prepare psychological profiles for use by interrogators as well as to observe and offer feedback to these inten·ogators. Such a role may violate longstanding core clinical principles such as 'do no harm' and 'respect confidentiality'. As science advances, new ethical issues crop up. Advances in cognitive neuroscience and allied fields include the development of drugs that can improve performance on learning and memory tasks for both impaired and normal individuals; brain-imaging techniques that allow for early diagnoses of learning disabilities such as dyslexia; and the identification of genetic markers that may predict learning difficulties or prodigious potentials in young children. While exciting, such imminent breakthroughs raise vexing questions about what use should be made of this new knowledge, by whom, at what cost, and with what safeguards (Sheridan ef al., 2005). Recognising this 'growing quagmire', The Council of Scientific Society Presidents recently convened an Ethics in Science committee to develop recommendations for more than 60 member organisations concerning the formulation of appropriate codes of ethics. The unparalleled power of market forces and powerful new digital media also impact the field of psychology. Researchers feel tremendous pressure to bring in grants that will increase both the prestige and budgets of their sponsoring institutions (Verducci & Gardner, 2006). Meanwhile, clinical psychologists report that the rise of the internet has affected everything from the types of addictions reported by their clients to the marketing one must do to attract clients. Such cultural and technological changes have ushered in a host of new ethical challenges with which contemporary psychologists must contend. In short, the field of psychology has always grappled with ethical dilemmas, but new technologies and powerful societal trends have brought forth ethical conundrums for which traditional paradigms may not suffice. In this context findings from the GoodWork Project may prove useful. Launched in 1996, the project is a multi-site collaboration between psychologists Howard Gardner, William Damon and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. 'Good work' is defined as work that exhibits three 'E' traits: it is (1) Exct:llent in quality; (2) carried out in an Ethical manner; and (3) Ellgaging to its practitioners. The goal of this endeavour is to illuminate the supports and obstacles to producing such work in a time when technological advances are occurring rapidly and market forces are powelful and often unchecked. Over the past decade, the GoodWork Project (GWP) research team has conducted over 1200 in-depth interviews across a wide range of professions from journalism to genetics to medicine. Findings have been reported in numerous books and articles (see Fischman ef al., 2004; Gardner et 01., 200 I: Gardner & Shulman, 2005; Verducci & Gardner 2006). In this article we focus particularly on the 'second E': the supports and obstacles to carrying out work that is ethical. Specifically, we report on three key November 200; Ethk'~ findings that may be useful to psychologists in thinking about the most pertinent ethical issues to the field today. Keeping hats straight One of the project's findings is that ethical issues arise when people wear too many professional 'hats' simultaneously or try to switch back and forth rapidly between possibly incompatible 'hats.' In our study of genetics, for example, we found that advances in the field created private-sector opportunities for geneticists employed by universities as academic researchers and professors. Academics are expected to report research openly and share data; entrepreneurs often carry out secret lines of work. Attempts by some of these professionals to don two hats simultaneously - that of academic and entrepreneur - increased the likelihood of ethically questionable conduct and even outright misconduct. Comparable ethical conflicts can arise in psychology. Consider a psychologist who tests and treats schoolchildren experiencing learning difficulties while simultaneously accepting commissions from a pharmaceutical company for promoting a particular neurocognitive­ enhancing dlug. Or imagine a research psychologist who begins a study testing the effectiveness of this same neurocognitive­ enhancing drug while simultaneously providing consulting services to the drug maker. The pressures to skew findings or to hide disappointing results are patent. It is, in large part, for this reason that Kwiatkowksi and Winter (2006) observe: 'As soon as one moves beyond one's professional reference group to interact with others, it is extraordinarily important to know what you really know, what you thought you knew, what you imagined, where theory is infonning or conversely biasing you, and the limits of your understanding' (p.163). Such self­ awareness is critical to avoid succumbing to the aforementioned pressure to skew findings or hide disappointing results. The donning of too many hats can also lead to less blatant ethical issues - what we've tenned compromised work (Gardner, 2005). The research psychologist at a typical university may be expected to teach several classes, advise graduate students, serve on committees, read admissions folders, referee journal articles, write recommendation letters, secure grants, conduct research and publish the results of their research. The impact of donning so many different hats in rapid succession can lead to a variety of ethical peccadilloes: skimming student work; overlooking a case of suspected plagiarism; missing deadlines on promised recommendation letters; relying too heavily on research assistants; and taking shortcuts in that research. The GWP offers several suggestions for handling the 'hat problem.' Consider the psychologist who is both clinician and consultant. Doing 'good work' requires COMMON ETHICAL DILEMMAS IN PSYCHOLOGY I. Maintaining confidentiality 2. Maintaining professional relationships with clients 3. Altering or ignoring data in order to publish 4. Responding to the ethically questionable conduct of colleagues 5. Balancing commitments to teaching. clients, research. committees, etc. such professionals to make a clear choice between these conflicting hats - for example, no longer seeing patients of a certain type while consulting about a particular drug. Avoiding such a choice risks failing to embody the values of one or both of the potential hats they are attempting to wear. Technological or cultural changes within a profession can also lead professionals to take on more hats than they can responsibly handle or to don hats for which they are inadequately trained. For example, a clinical psychologist abmptly expected to incorporate brain­ imaging results into diagnoses may be donn.ing a hat for which more training is required. In both of these cases, doing good work requires these professionals to prod their respective organisations for the time and training that will allow them to do work that is both ethical and excellent. Should such prodding prove ineffective, the psychologist is advised to seek employment elsewhere (cf. Hirschman, 1970). Seeking alignment among stakeholders Cultural and technological changes have ushered in a host of new ethical challenges Our interviews of professionals across a variety of fields document a pervasive desire to do good work. However, we also discovered that an individual's ability to do good work within their profession is dependent not only upon that particular individual's motivation, expel1ise and resources but also upon the alignment of the profession as a whole. In other words, individual psychology must mesh with sociological institutions and forces. A profession is in alignment when the various stakeholders within that profession hold similar beliefs about the values, activities, goals and rewards of the work being carried out. Conversely, a profession is 'misaligned' when different stakeholders within the profession are guided by ______________E November 2007 www.thepsychologist.org.uk I -1 Ethk' contradictory goals and values or hold competing beliefs about the pathway along which the work should be pursued (Gardner et ai., 2001). Both clinical and research psychology currently face ethical threats due to misalignment. In the United States - where most of our research has been carried out ­ clinical psychologists experience disheartening misalignment when they recommend a particular level of treatment for a patient only to have that patient's managed care organisation agree to reimburse only a fraction of the presCiibed treatment or to reject the claim completely. Such a situation can lead to the ethical dilemma of having to choose between prematurely terminating with a patient; continuing to treat the patient without guarantee of compensation; or, in the extreme, lying about the condition (for example by giving a formal diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder when in fact you think that a person's tendencies actually fall short of the criteria). Research psychologists can experience misalignment when pressure from their institutions to win large research grants leads them to pal1ner with organisations whose mission and values conflict with their own. Imagine, for example, a researcher interested in testing (and possibly rebutting) the claims made by Herrnstein and Murray (1994) about racial differences in intelligence. Should that researcher seek funding from The Pioneer Fund, one of a tiny handful of organisations that fund research in the area of intelligence and race but one of whose founders supported both eugenics and racial segregation? Such a partnership might allow the researcher to carry out the study but at the cost of his or her findings possibly being used by the study's sponsor in a manner contrary to the researcher's own ethical beliefs. While good work is unquestionably easier to carry out in a profession that is well aligned, one of our project's more surprising findings is that some professionals are motivated to do good work by their profession's misalignment. Such individuals seek to reduce their field's misalignment by strengthening the core values of their profession. Geneticists have founded the Council on Responsible Genetics; journalists rally to the Committee of Concerned Journalists; and many businesses explicitly adopt a code of socially responsible business practices. ~r-------------- I The Psychologist Vol 20 No II Still active at age 91, Jerome Bruner seems a worthy candidate for a 'psychological trustee' Acknowledging and debating - rather than ignoring or obscuring - the current examples of misalignment in psychology, then, can motivate individual practitioners and institutions to confront these problems head-on and perhaps bring about greater alignment. The role of mentors The GoodWork Project has documented the importance of strong mentors within a profession. A worrying trend that emerged in our interviews with aspiring professionals is their readiness to cut corners and compromise their ethical moorings in order to compete with their peers (Fischman et ai., 2004). They wanted to do good work, but felt pressured by their cut-throat professional environment to postpone good work until they had achieved success. Respondents across all professions commented on the imp0l1ance of strong role models, or mentors, to act as a buffer against such pressures. The vertical support offered by these experienced and knowledgeable 'senior workers' played an integral role in respondents' continuing pursuit of good work. Those who lacked such SUpp0l1 bemoaned its absence and felt more susceptible to the temptation of quick money or quick fame. The nature of mentorship varied across professions according to the presence or absence of formal training. Formal mentors were more common in genetics, law and higher education, where guidance from an experienced and knowledgeable practitioner is a prescribed part of one's professional development. In contrast, informal mentors were the norm in business, 'philanthropic' organisations (e.g. foundations, grantmakers) and journalism. Good workers in these latter fields benefited from unofficial, on-the-job mentors as well as paragons whom they did not know personally but admired from afar (cf. Simonton, 1994). Given the many years of training required of research and clinical psychologists, it is not surprising that mentorship in the field of psychology has been formalised. An aspiring research psychologist receives guidance and supervision from an academic adviser and may pursue a series of postdoctoral positions under the supervision of experienced researchers. These apprenticeships enable a deepening of disciplinary knowledge and an extension of professional networks. Similarly, an aspiring clinical psychologist must log hundreds of hours of supervised counselling before obtaining clinical certification. In both cases, formal apprenticeships provide an opportunity for the young professional to learn how to navigate ethical issues in the field of psychology, whether relating to publication credit or client confidentiality. In light of the important role that mentors play in motivating good work, we urge young psychologists to take care when selecting their mentors. It is not the case that any mentor is better than none. Individuals who are overcommitted lack the time to provide consistent and high­ quality mentorship. It is difficult to develop November 2007 a deep and meaningful relationship with mentors who are spread too thin. At the other extreme, overly restrictive mentors do not allow young professionals the needed space to develop their skills and follow their passions. Lastly, individuals who seek mentorship roles for personal gain make poor candidates, as the quality of their mentors hip will be limited by their own motivations. It goes without saying that individuals with sub-par ethical records are unlikely to make good mentors. In our work, we have identified such individuals as 'anti­ mentors' or 'tormentors' and we have observed that they often serve an impOitant purpose, albeit not as mentor. Instead, they can alert both budding and veteran psychologists to their own and their profession's values and goals and encourage reflection on the boundary where good work ends and compromised work begins. In our interviews with novice professionals, three qualities emerged as ones to look for in a mentor: perseverance, creativity and commitment (Fischman & Gardner, 2005). Individuals told us about mentors who persevered with work they felt was important despite challenging situations. Such mentors demonstrated tlu'ough their courageous actions that it is possible to cany out good work in the face of obstacles. Individuals were also inspired by mentors who pushed the limits of their profession in creative ways and, as a result, made important contributions to their profession while simultaneously making their work personally meaningful. Finally, young professionals admired the commitment their mentors displayed to canying out the mission of their profession while remaining mindful of the social impact of their work. We suggest four strategies for helping young psychologists to select a mentor who will nurture the qualities of perseverance, creativity and commitment within themselves (Fischman & Gardner, 2005). First, seek a mentor whose working styles, beliefs and worldviews complement your own, as this fit should foster the development of a personal relationship. Second, if you have trouble identifying a mentor within your profession, consider broadening your search. The professionals we interviewed frequently refelTed to influential individuals outside of their profession, such as family members and teachers. Third, it is often valuable to November 2007 identify multiple mentors who serve different purposes. For instance, you migbt have one mentor who can offer you sage career advice, another who is a good listener and a third who helps you develop your professional skills. Fourth, consider the fact that inspirational role models may not always be available or even alive. While unable to provide personalised advice about current issues, influential figures remote in space or time often provide powerful examples of perseverance, creativity and conunitment. In addition to mentors and anti-mentors, a role we refer to as a 'trustee' characterises well-aligned professions. Trustees are leaders in their field who have carried out good work throughout the course of their careers and continue to exelt their influence on their professions. They use their position of professional 'They wanted to do good work, but felt pressured by their cut-throat professional environment' eminence in a disinterested way to preserve the field's values and goals. They may also serve an important role in setting new norms for dealing with ethical issues that emerge as technological advances, market forces and political fluxes continue to exert their influence on all professions. Trustees exist in many areas. For example, the late Isaiah Berlin was considered by many to be a trustee of British intellectual life. On the global scene, former Irish President Mary Robinson occupies a trustee role. Trustees in the field of psychology, for example, could help to establish nOlIDS for research studies involving the new digital media or the appropIiate use of neurocognitive­ enhancing drugs. Still active at age 91, Jerome Bruner seems a wOlthy candidate for a psychological trustee (Bruner, 1983; Olson, 2007). Bruner has had a profound impact on both psychology and education. His theoretical oeuvre is extensive and includes such topics as adult problem-solving, the new look in visual perception, children's cognitive development and modes of representation, the process of teaching as one of knowledge building rather than knowledge transfer, and the role of culture in learning and teaching. Beyond his u-npOitant theoretical contributions, Bruner worked to establish cognitive psychology as an important area of study at a time when behaviourism dominated the field. He was also involved in numerous educational projects in which he oversaw the practical application of his ideas Bruner's engagement in shaping tbe norms of psychology and active involvement in the responsible application of his work exemplify our definition of a trustee. We had the oppOitunity to ask Bruner about psychologists in Britain who occupied the role of trustee. VelY quickly, he came up with the name of Frederic Bartlett, long-time professor at Cambridge, and one of the forerunners of modern cognitive psychology. Bartlett was widely respected for his scholarly accomplishments, his judgement of complex issues, and his personal integrity. It is perhaps not an accident that the senior Bartlett took an interest in the young Bruner; trusteeship can be passed from one generation to the next and the process can be quite deliberate. There can also be specific roles for which trustees are groomed: election to honoraly societies or to positions like masters of colleges are often carried out with the role of present or future trustee in mind. However, tnlsteeship can also arise when there is a widely perceived gap within a profession: when most Amelican physicists uncritically embraced the goal of the Manhattan project to develop the first atom bomb, physicist Joseph Rotblat was already pondering the dangers of a nuclear world. It is also possible to think of prominent psychologists who have had less positive effects on the field. When educational psychologist Sir CyIil Burt died in 1971, he was considered a leading figure in psychology, perhaps even a trustee (Tucker, 1994). His findings on the heritability of intelligence were cited frequently by well­ known scientists, including psychologists Arthur Jensen (1969) and Hans Eysenck (1973) and engineer-turned-eugenicist William Shockley (1972). In the years that followed Burt's death, however, scientists discovered oddities and discrepancies in his most famous research involving monozygotic twins reared apart (Tucker, 1994). When psychologist Leon Kamin examined Burt's data and publications, he uncovered questionable sampling methods and IQ measurement procedures, false citations, and cOlTelation coefficients that remained impossibly consistent over a 30­ year period of studying different samples ----------------lE www.thepsychologist.org.uk I _I Ethic< of twins, A once lauded psychologist, Bun could now be considered a footnote of inesponsible research in the history of psychology (Lewontin et ai" 1984), Conclusion New ethical issues require new tools for pursuing good work, Our GoodWork Project suggests that psychologists should (I) think about the various hats they don, (2) consider issues of alignment within their field and seek to COD'ect areas of misalignment, and (3) identify mentors, anti-mentors, and trustees who can help to exemplify and delimit the boundaries of good work in psychology, As they seek to pursue the three Es of GoodWork, psychologists should also consider the four Ms: (1) What is the Mission of my field? (2) What are the positive and negative Models that I must keep in mind? (3) \l hen I look into the Minor as an individual professional, am I proud or embarrassed by what I see? and (4) When I hold up the Mirror to my profession, am I proud or embarrassed by what I see? (Verducci & Gardner, 2006), Psychologists who ask and seek powerful answers to these questions will be more likely to do good work. In the spirit of propagating good work, we have compiled our insights into an educational intervention, The GoodWork Toolkit includes several powerful ethical dilemmas that emerged during our interviews; these dilemmas are described in a manner that promotes deep reflection about the merits, challenges, and facilitators of good work, The cuniculum was inspired by our interviews with aspiring and young professionals who repeatedly defended their decision to postpone good work until they had 'made it' in today's cutthroat, market-driven environment (Fischman et ai., 2004), Deeply troubled by this mindset, we believe it is imperative for educational institutions to prepare individuals to cany 'It is not enough ... simply to carry out one's individual work in an excellent, ethical and engaging manner...' out ethical, not just excellent, work, (Barendsen & Fischman, 2007; goodworkproject,org) The Toolkit is currently being used in a number of secondary and postsecondary schools in the United States, The Toolkit prepares new professionals to pursue good work before they enter the field, Once established in the field, new and experienced professionals alike must not lose sight of the good work trifecta (excellent, ethical, and engaging work) or the tools that make it possible (hats, alignment, mentors), It is not enough, Has the increasingly global village influenced the 'hat' problem in psychology? If so, how? Have your formal or informal mentors been more influential? In what ways? How do the areas of psychology with which you are most familiar fare on the mirror test? What 'hats' do you don as a psychologist, and have they led to conflicts or compromised work? Whom would you nominate as a psychological trustee? What qualities must today's trustees exhibit? Have your say on these or other issues this article raises, E-mail 'letters' on psycholog;st@bps,org,uk or contribute (members only) via www,psychforum,org,uk. ~I-------------­ I The Psychologls[ Vol 20 No II • Scott Seider is an Instructor in Education and advanced doctoral candidate at Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA. E-mail: seidersc@gse,harvardedu, • Katie Davis is (( doctoral student and research assistant at Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA: E-mail: daviska@gse,harvardedu, • Howard Gardner is Hobbs Professor of Education and Cognition. Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA. E-mail: howard@pz,harvardedu, References Barendsen, L. & Fischman, W (2007),The GoodWork Toolkit: From theory to practice, In H, Gardner (Ed,) Responsibility at work: How leading professionals oct (or don't oct) responsibly. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Bloche, M, & Marks,J, (2005), Doctors and in(errogacors at DISCUSS AND DEBATE however, simply to cany out one's in.dividual work in an excellent, ethical and engaging manner and then move on to a new project or client. Leading psychologists need to take on the role of trustee: as the playwright Moliere declared: 'We are responsible not only for what we do, but for what we don't do.' A new covenant is needed between psychologist and society, one that takes the psychologist beyond scientific curiosity and the client roster. This covenant requires individuals to assume a responsibility to monitor the way in which psychological work is carried out, understood, and used by others, both within the field and across the broader society, Guantanamo Bay, New England Journal a( MediCfne,353, 6-8, Bruner, j,S. (1983), In searcll of mind, New York: Norcon, Eysenck, H.]. (1973), The inequollW of man, London: Temple Smirh, Fischman,W & Gardner, H, (2005), Inspiring good work, Greater Good, Spring/Summer 2005, Fischman, W, Solomon, B" Greenspan, D, & Gardner, H, (2004), Making good: How young people cope witll moral dilemmas at work, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Gardner, H, (2005), Compromised work, Daedalus Summer, 2005, Gardner, H" Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Damon,W (200 I), Good work: Wilen excellence and ethics meet New York: Basic Books, Gardnel~ H. & Shulman, L. (2005). The professions in America coday: Crucial but fragile. Daedalus, Summer 2005. Herrnstein, R, & Murray, C. (1994), Tile bell curve: Intelligence and class structure jn American fjfe. New York: Free Press, Hirschman.AO, (1970), Exit, voice, and loyalty. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Jensen.AR. (1969), How much can we boost IQ and scholastIC achievement? Harvard Educotianal Review, 39( I), 1-123 KWiatkowski, R, & Winter, B. (2006), Roots, relativity and realism: The occupational psychologist as 'scientist-practitioner'. In D. Lane & S, Corrie (Eds,) The modern scientist practil.i.oner:A guide to practice in psychology, London: Routledge. Lewontin, R" Rose, S. & Kamin, L (1984), Not in our genes, New York: Pantheon. Olson, D, (2007), Jerome Bruner, London: Continuum Press. Pope, K, & VenerY (1988), Ethical dilemmas encountered by members of the American Psychological Association: A national survey. American Psychologist, 47, 397--411. Sheridan, K., Zinchenko, E, & Gardner, H, (2005). Neuroerhics in education. In J. Illes (Ed,) Neuroethics: De(illing the issues /n research, praQlCe, and policy (pp,26S-27S). New York: Oxford University PI'ess, Shockley, WB, (1972), Dysgenics, geneticity, raceology: A challenge to the intellectual responsibility of educacors, Phi Delta Kappon, 297-307. Simonton, D, (1994). Greatness, New YOI'k: Guilfor'd, Tucker~ WH, (1994), Fact and fiction in the discovery of Sir Cyril Burt's fiaws,Jaumol a(the History of Ule Behavioral Sciences, 30(4), 335-347 Verducci, S. & Gardner, H, (2006). Good work: Its nature, its nurture, In F Huppert (Ed,) Tile science o( happiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. November 2007